REVIEW: Demons, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Demons, Fyodor Dostoevsky (1871; trans. Constance Garnett, Penguin Classics, 1916).

The Russian Revolution should not have been a surprise. For decades leading up to it, Russia was gripped by an ever-rising wave of sadistic revolutionary terrorism. Gary Saul Morson describes it like this:

Country estates were burnt down and businesses were extorted or blown up. Bombs were tossed at random into railroad carriages, restaurants, and theaters. Far from regretting the death and maiming of innocent bystanders, terrorists boasted of killing as many as possible, either because the victims were likely bourgeois or because any murder helped bring down the old order. A group of anarchocommunists threw bombs laced with nails into a café bustling with two hundred customers in order “to see how the foul bourgeois will squirm in death agony.”

Instead of the pendulum’s swinging back—a metaphor of inevitability that excuses people from taking a stand—the killing grew and grew, both in numbers and in cruelty. Sadism replaced simple killing. As Geifman explains, “The need to inflict pain was transformed from an abnormal irrational compulsion experienced only by unbalanced personalities into a formally verbalized obligation for all committed revolutionaries.” One group threw “traitors” into vats of boiling water. Others were still more inventive. Women torturers were especially admired.

What do you think was the response of “moderate” Russians to all of this? Academics and journalists and liberal politicians and forward-thinking businessmen, that sort of people. If your guess is that it horrified them and caused them to grudgingly support the forces of order, you would be...wrong. In fact, quite the opposite: making excuses for terrorism became trendy. Lawyers and teachers and doctors and engineers held fundraisers for terrorists, donated to charities that supported insurrectionary behavior, and turned their offices into safe houses. Apparently chaos and death were one thing, but it was much, much scarier for your friends and neighbors to think you might be a reactionary. Naturally this same class of people were the first to be herded into the camps, or into the cork-lined cellars in the basement of the Lubyanka. Despite all my boundless cynicism about human nature, I still can’t quite believe that this all actually happened.

Dostoevsky predicted it 50 years beforehand.

The opening of Demons tries to fool you into thinking it’s a comedy of manners about liberal, cosmopolitan Russian aristocrats in the 1840s. The vibe is that of a Jane Austen novel, but hidden within the comforting shell of a society tale, there’s something dark and spiky. Dostoevsky pokes fun at his characters in ways that translate alarming well into 2020s America. Everybody wants to #DefundTheOkhrana and free the serfs, but is terrified that the serfs might move in next door. Characters move to Brookl…I mean to St. Petersburg to start a left-wing magazine and promptly get canceled by other leftists for it. Academics endlessly posture as the #resistance to a tyrannical sovereign (who is unaware of their existence), and try to get exiled so they can cash in on that sweet exile clout. There are polycules.1

As the book unfolds, the satire gets more and more brutal. The real Dostoevsky knew this scene well — remember he spent his early years as a St. Petersburg hipster literary magazine guy himself — and he roasts it with exquisite savagery. As a friend who read the book with me put it: the men are fatuous, deluded about their importance, lazy, their liberal politics a mere extension of their narcissism. The woman are bitchy, incurious about the world except as far as it’s relevant to their status-chasing, viewing everyone and everything instrumentally. Nobody has any actual beliefs, and everybody is motivated solely by pretension and by the desire to sneer at their country.

But this is no conservative apologia for the system these people are rebelling against either, Dostoevsky’s poison pen is omnidirectional. Many right-wing satirists are good at showing us the debased preening and backbiting, like crabs in a bucket, that surplus elites fall into when there’s a vacuum of authority. But Dostoevsky admits what too many conservatives won’t, that the libs can only do this stuff because the society they despise is actually everything that they say it is: rotting from the inside, unjust, corrupt, and worst of all ridiculous. Thus he introduces representatives of the old order, like the conceited and slow-witted general who constantly misses the point and gets offended by imagined slights. Or like the governor of the podunk town where the action takes place, who instead of addressing the various looming disasters, sublimates his anxiety over them into constructing little cardboard models.2 If there’s a vacuum of authority, it’s because men like these are undeserving of it, failing to exercise it, allowing it to slip through their fingers.

All of this is very fun,3 and yet not exactly what I expect from a Dostoevsky novel. It’s a little…frivolous? Where are the agonizingly complex psychological portraits, the weighty metaphysical debates, the surreal stroboscopic fever-dreams culminating in murder, the 3am vodka-fueled conversations about damnation? Don’t worry, it’s coming, he’s just lulling you into a false sense of security. After a few hundred pages a thunderbolt falls, the book takes a screaming swerve into darkness, and you realize that the whole first third of this novel is like the scenes at the beginning of a horror movie where everybody is walking around in the daylight, acting like stuff is normal and ignoring the ever-growing threat around them.

To understand what happens next, it helps to have read some Turgenev. His most famous work, Fathers and Sons, is of a piece with the most lurid boomer fantasies. The basic plot is that there are some genteel Russian liberals, good New York Times readers, people with all the right views. Their kids come back from college and are espousing all this weird stuff: stuff about white fragility and transgenderism and boycotting Israel, stuff that makes their nice liberal parents extremely uncomfortable. But it’s okay, you see? The kids magnanimously realize that their parents were once cool revolutionaries too, and the parents make peace with the fact that the kids are just further out ahead than they are, and everybody feels good about themselves because if the kids have seen far, it’s only by standing on the shoulders of giants. The important thing to understand is that everything about this plot is identity validation wish-fulfillment for the boomer liberal parents (like Turgenev himself). It’s the political equivalent of that YouTube genre where Gen Z Afro-American kids rock out to Phil Collins.

The macro-structure of Demons mirrors this so closely, you can almost read the book as one long, savage parody of Fathers and Sons.4 The sunny opening section is a satire of the boomer liberals, and the big vibe shift part way in is their kids coming back from college. But that’s where things go off the rails. In this book, the next generation shares their parents’ anti-religious and anti-monarchist attitudes, but unlike in Fathers and Sons, the kids in Demons are disgusted by the hypocrisy and cowardice of their genteel liberal parents, and eager to plunge Russia into a hyper-totalitarian nightmare. The exact contours of that nightmare are something they frequently argue about and change their minds over, but they can all agree that it will need to begin with an enormous mountain of skulls, and that their town is as good a place as any to start.

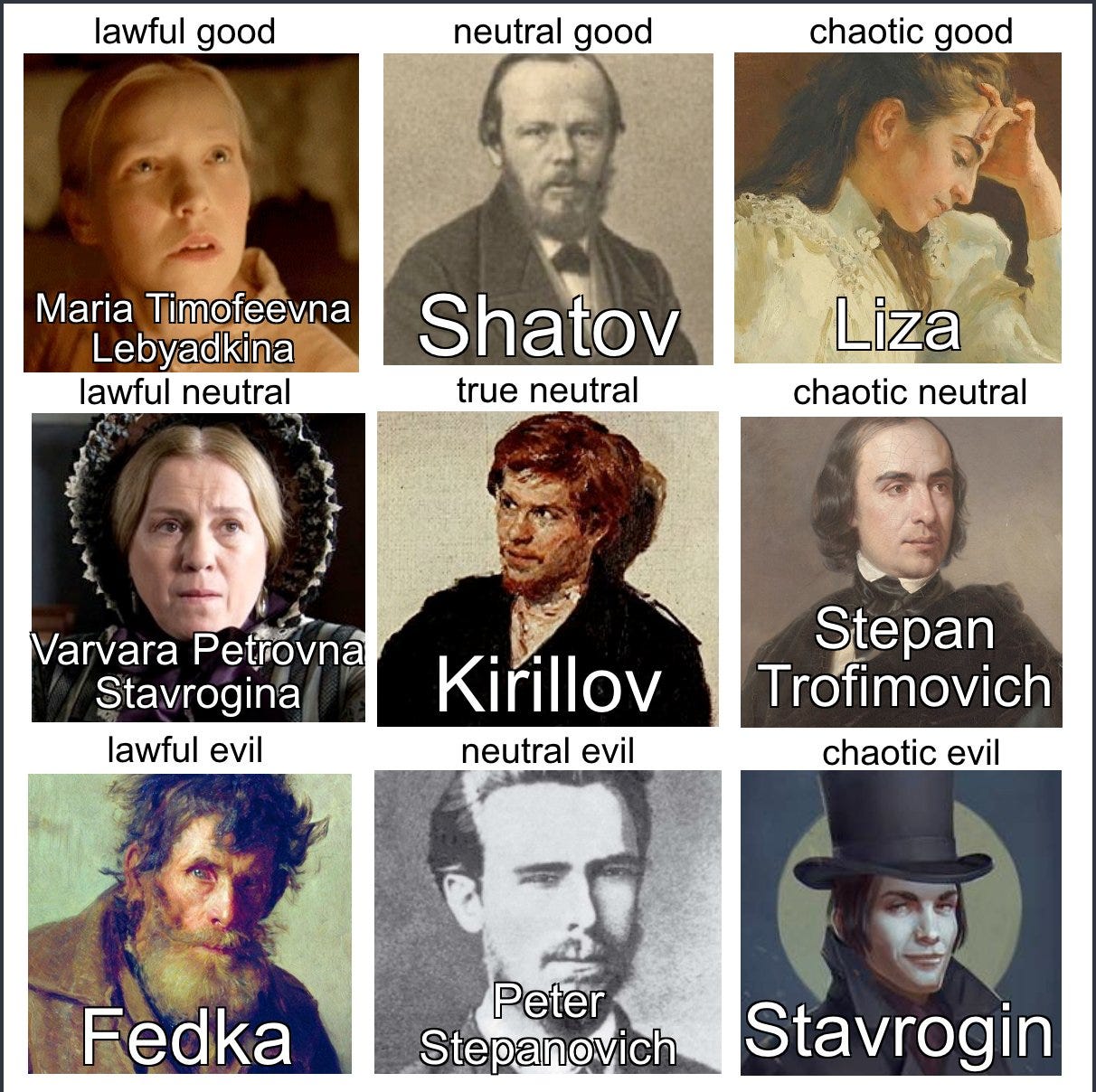

Dostoevsky’s other works put individuals front and center, his stories have unbelievably rich characterization (Nietzsche once said that Dostoevsky was the greatest psychologist to ever live), because for Dostoevsky the very highest stakes, the most important questions in the world, were about the damnation or salvation of individual souls. But Demons is different: here the characters all blur together, their names are disgorged to you in a never-ending torrent, and only a few of them are distinctive in any way.5 How could Dostoevsky think these people don’t matter? It’s because they aren’t real people anymore. It’s because they’re possessed. Their brains have been scooped out and all you can see in their eyes is a writhing mass of worms. Their ideas and ideologies have hollowed them out and are wearing their skins as suits.

But what if the ideas don’t matter either? It’s easy to interpret the second half of Demons as a novel of ideas, but it really isn’t. Your first clue is that the ideas are just so goofy. There’s one guy who thinks that by killing himself he will become God (don’t ask, it’s Dostoevsky, man). Another has written a book with ten chapters, explaining how “Beginning with the principle of unlimited freedom I arrive at unlimited despotism,” and proposing a method of brainwashing for reducing ninety percent of humanity to a mindless “herd.” Yet another thinks that everything can be solved by killing one hundred million people, but laments that even with very efficient methods of execution this will take at least thirty years.6 My own favorite might be the guy who refuses to explain what his system is, but just smugly declares that since everybody is going to end up following it eventually, it’s pointless for him to explain it.

In a novel about political radicalism you might expect the ideas to take center stage, but here they’re treated as pure comic relief (if you’ve read The Man Who Was Thursday, the vibe is very similar). The guy who wants to kill all of humanity and the guy who wants to enslave all of humanity have some seriously conflicting objectives (and don’t forget the guy who just wants to kill himself and the guy who refuses to say what his goal is), yet they all belong to the same revolutionary society. The leader of their society takes it to an extreme, he has no specific ideas at all. His political objectives and philosophical premises are literally never mentioned, by him or by others. What he has is boundless energy, an annoying wheedling voice,7 and an infinite capacity for psychological cruelty. But all these impressive capacities are directed at nothing in particular, just at crushing others for the sheer joy of it,8 at destruction without purpose and without meaning.

Does that seem unrealistic? That ringleader was actually based on a real life student revolutionary named Sergey Nechayev, whose trial Dostoevsky eagerly followed. Nechayev wrote a manifesto called The Catechism of a Revolutionary, here’s an excerpt from that charming document:

The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no personal interests, no business affairs, no emotions, no attachments, no property, and no name. Everything in him is wholly absorbed in the single thought and the single passion for revolution… The revolutionary despises all doctrines and refuses to accept the mundane sciences, leaving them for future generations. He knows only one science: the science of destruction… The object is perpetually the same: the surest and quickest way of destroying the whole filthy order… For him, there exists only one pleasure, one consolation, one reward, one satisfaction – the success of the revolution. Night and day he must have but one thought, one aim – merciless destruction.

The ideas don’t matter, because at the end of the day they’re pretexts for desires — the desire to dominate, the desire to obliterate the world, the desire to obliterate the self, the desire to negate.9 Just as in their parents’ generation the desire for status came first and wrapped itself in liberal politics in order to reproduce and advance itself, so in their children the desire for blood and death reigns supreme, and the radical politics serve only as a mechanism of self-justification and a lever to pull. This is not a novel about people, and it’s also not a novel about ideas. It’s a novel about desires, motives, urges, and the ways in which we construct stories to make sense of them.

But where do desires come from?

The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor once wrote a very long book about how the essential quality of secularization is the transition from what he calls “the porous self” to “the buffered self.” In pretty much every premodern society, people believe that their psyches are subject to benign or malign or simply alien influence from external forces and entities — gods, demons, faeries, curses, the evil eye, or Iwa. Contra many popularizers of Taylor, the crucial distinction isn’t that these forces are supernatural in nature, it’s that the boundary between inmost self and the outside world is vague and semi-permeable, and therefore that any one of our thoughts or desires might have arisen through outside influence.

In contrast, most modern societies believe in a self that is “buffered.” In this view there are a few limited, low-bandwidth ways that the external world can act on one’s innate nature, for instance via drugs or other body chemistry, and even these are often seen as revealing or disclosing previously hidden innate characteristics of one’s personality rather than as imposing something alien. Taylor argues quite convincingly that these two ways of viewing the self — porous vs. buffered — inexorably produce two different ways of viewing society and the world: premodern and modern. For example: if selves are porous, then we need to be extremely vigilant against the invasion or violation of our minds by hostile spirits, and we must be suspicious of what we want, because it might not really be what we want, but rather what something else wants through us. Conversely, if selves are buffered then our desires are just part of who we are, and in order to be true to ourselves, we need to explore them and act upon them.

It may have been reasonable to believe in a buffered self back in the days before the internet, but recent developments have made it clear that (as in so many things) the primitive superstitions were actually correct, and the enlightened modern view was just a lamer and dumber kind of superstition.10 Science fiction has long been fascinated with stories of infohazards — images or jokes or snippets of cognition that act like a Gödel sentence for the human mind and leave people braindead or mind-controlled. But such things long since slipped the shackles of fiction — we now have internet creepypasta that induces girls to become murderers and a genre of pornography that turns boys into girls.11 The noösphere is a vast ocean, and its abyssal depths teem with lifeforms and thoughtforms that seek to possess you and live out their blasphemous unlife through your mortal husk.

Dostoevsky obligingly gives us a character who’s clearly possessed in exactly this sense — a dissolute nobleman around whom the various radical conspiracies swirl. He is, simultaneously, a subversion of the brooding Byronic hero archetype that was so popular in 19th century European literature, and an eerie anticipation of the modern concept of the serial killer. How did he get this way? Remember the modern view of our desires is that they come from within us, and indulging them leads to inner harmony. But the older and truer view is that they can come from outside, force their way into our skulls through an opening, set their hooks in our brains, lay their eggs. These fledgling desires start out small and weak, but to indulge them is to feed them, grow them, until they take over their host and move its mouth and limbs around like a puppet. In this sense the porn addict, the drug addict, and the rage addict are all alike: sensual dissipation gets boring eventually, and you need harder and harder stuff to feel the same thrill, until one day you reach for something so hard you lose yourself forever.

The Dostoevskian twist to all this is that the proto-serial killer is far more sympathetic, and ultimately more redeemable, than the revolutionaries. The radicals' motivations spring from the same emotional source as his, theirs are just sublimated into politics, which is why the form of the dystopia doesn't really matter to them, all that matters is that there be a boot stomping on a human face. The sexual sadism of the serial killer is unflinchingly portrayed as less disordered and less socially destructive than its political equivalent and, ultimately, as rather basic. It's actually quite easy to miss all of this because it's so deeply at odds with modern sensibilities. Not just “serial killers are better than communists actually,” but also “serial killers are really pretty boring actually,” and all from the guy who just invented serial killers.12

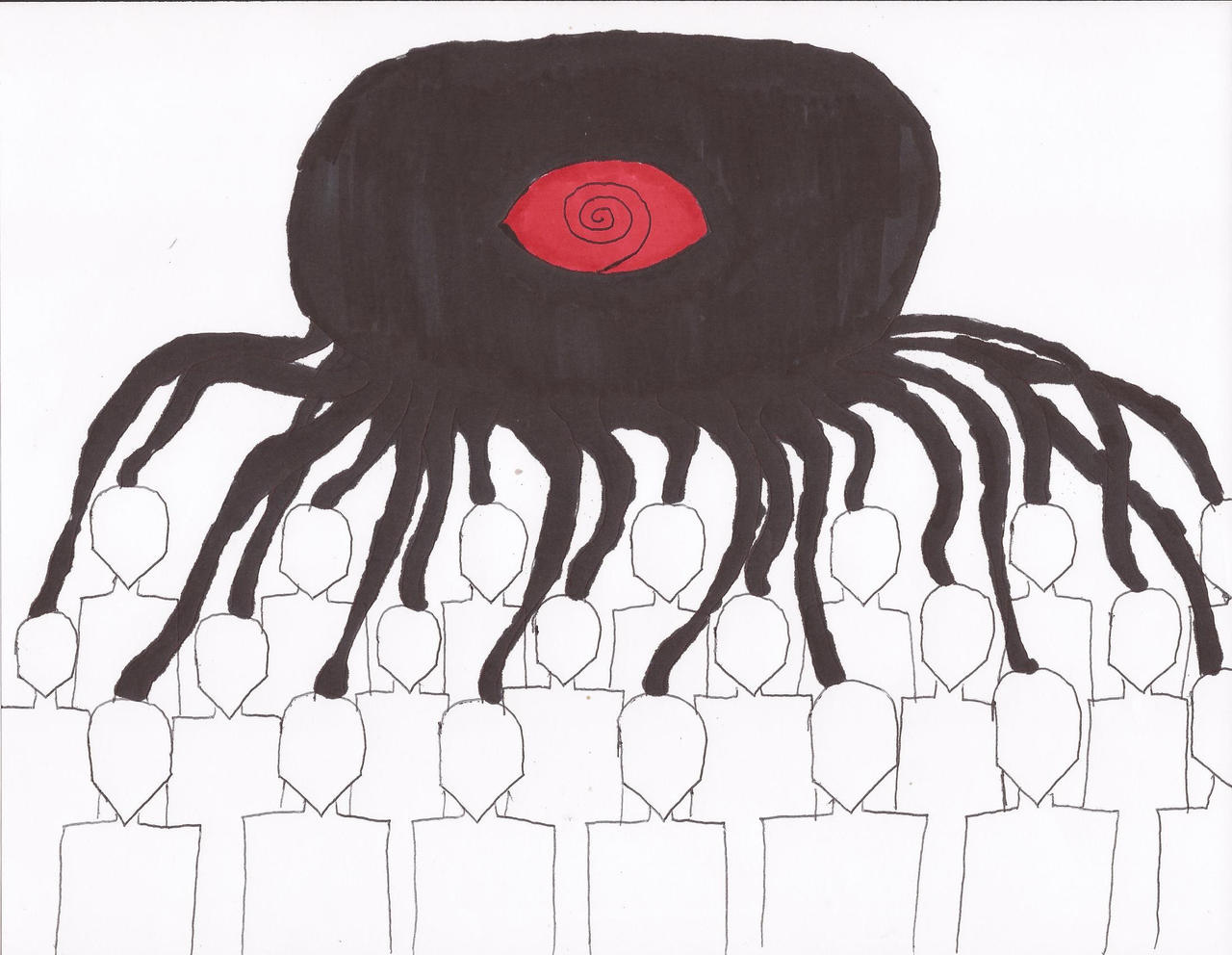

But what if the radicals aren’t sublimating anything at all? What if there’s another kind of demon, another kind of infohazard, another kind of meme, which rather than infecting or possessing individuals, instead tries to do that to entire societies? Such a being might still work through individuals, the way a Haitian voodoo spirit speaks through a chwal, but here the individual puppet is not a target, but rather an instrument or a transmission vector. The internet jargon for such a being is an “egregore,” and you’ve encountered them before: the bizarre fad that sweeps through a middle school class like a wildfire, the war fever that grips a nation and turns it overnight into a basket of bloodthirsty lunatics. Dance crazes, viral TikTok challenges, internet-mediated mental illnesses. There’s a classic Futurama gag involving the Brain Slug Party, but the real joke is that every party is the Brain Slug Party, they’re all egregores. Have you ever spoken with somebody who had hashtags in their Twitter bio? If you looked carefully, you may have seen the slender, silvery proboscis emerging from the back of their neck and vanishing into the ether. If you listened carefully, you may have heard the alien metallic clacking of the egregore’s mandibles, as it sent messages down that tube for the meat puppet to vocalize.

Sometime in the mid-19th century, an egregore was born in the Russian Empire. It went by a thousand different names — among them: anarchism, communism, nihilism, democracy. What’s that? Those four ideologies are completely opposed to one another? That’s the entire point! It wasn’t actually any of those things, it was an egregore, its true name was something like Melkhorbalai or Uztaa-Binoreth. It wore those other names like skins when it was convenient to do so, which is why in the real life history of 19th century Russia we see countless examples of individuals switching between communism, anarchism, and democracy like they were flavors of ice cream.

The egregore wanted none of these things: it wanted to grow, to spread, to manifest itself into this reality. Madly, it willed destruction, and the more destruction it caused the stronger it got, and the easier further destruction became, a runaway exothermic reaction endlessly feeding on itself. So the reformist zeal of the 1840s became Nechayev’s insane nihilism of the 1870s, then the even more insane terrorism of 1900-1917 with which I opened this review, until finally, strengthened by half a century of blood sacrifice, that rough beast slouched towards St. Petersburg to be born. The trauma of that birth ripped apart first Russia, then Europe, then it almost ate the rest of the world too.

Could anything have stopped it sooner? In Dostoevsky’s story there’s one character who tries lamely to stand in the way of the swirling, coalescing, immaterial malevolence. He is a reactionary, a newly-freed former serf,13 and (like Dostoevsky himself) a repentant former revolutionary. He’s young and hip, but has old and edgy views, a perfect stand-in for online “trads.” Given Dostoevsky’s own views it would be easy to make him the hero of the story, but Dostoevsky is too great a writer for that, and instead makes him a pathetic LARPer:

“I only wanted to know, do you believe in God, yourself?”

“I believe in Russia… I believe in her orthodoxy.… I believe in the body of Christ.… I believe that the new advent will take place in Russia.… I believe…” Shatov muttered frantically.

“And in God? In God?”

“I… I will believe in God.”

How great a description is that of all the crusader-avatar twitter accounts named “DeusVult1571”? Imagine one of them blubbering: “I believe in based aesthetics… I believe in Western civilization… I believe in the Hajnal line… I believe…” Ah, but do you believe in God? Probably some of them do, but for many others it’s a pose, or a meme, or a philosophical premise that they must accept in order to turn the rest of the brand they’ve assumed into a self-consistent whole.14 For these, the god they worship is just another egregore — one small and weak for now, less threatening perhaps than some others, but feed it, let it grow, and see how fast it turns on you.

The other force that could have resisted the growing darkness is the parents’ generation, the liberals of 1848, Turgenev’s boomers. We already know how that turned out in real life, but while Dostoevsky didn’t live to see it happen, he had these peoples’ number. Once so bold in condemning their government and sneering at their civilization, they are suddenly timid in the face of their children, terrified of being seen as uncool or conservative or just not with it. That’s a good way to raise a psycho, and Dostoevsky more than hints that everything which follows is ultimately their fault. And it’s a bad way to face down an egregore. Doing that requires boldness and… well:

“But this is premature among us, premature,” he pronounced almost imploringly, pointing to the manifestoes.

“No, it’s not premature; you see you’re afraid, so it’s not premature.”

“But here, for instance, is an incitement to destroy churches.”

“And why not? You’re a sensible man, and of course you don’t believe in it yourself, but you know perfectly well that you need religion to brutalise the people. Truth is honester than falsehood…”

“I agree, I agree, I quite agree with you, but it is premature, premature in this country…” said Von Lembke, frowning.

“And how can you be an official of the government after that, when you agree to demolishing churches, and marching on Petersburg armed with staves, and make it all simply a question of date?”

“Premature, premature,” is what the useless normies will bleat when our own radicals are blowing up Mt. Rushmore and pulling down statues of George Washington. Who are these radicals? I have no idea what the egregore will call itself this time. It doesn’t matter. Its true name sounds to human ears like a high-pitched mechanical screeching and clicking, a sound calculated to drive men mad, and to drive madmen into making it real.

In an incredible bit of translation-enabled nominative determinism, the main cuckold is a character named Virginsky. I kept waiting for a “Chadsky” to show up, but alas he never did.

Look, the fact that he’s sitting there painting minis while the world burns makes the guy undeniably relatable. If you transported him to the present day he would obviously be an autistic gamer, and some of my best friends, etc., etc. Nevertheless, though, he should not be the governor.

For some reason, there are people who are surprised that Demons is funny. I don’t know why they’re surprised, Dostoevsky is frequently funny. The Brothers Karamazov is hilarious!

Further evidence for this reading: the book contains a character, the great writer “Karmazinov”, who is a straightforward expy of Turgenev himself.

This one probably seems less funny after the 20th century than it did when Dostoevsky wrote it.

To Dostoevsky’s own surprise, when he wrote the main bad guy of the story, he turned out a very funny, almost buffoonish figure. He may be the most evil person in literature who’s also almost totally comic.

Dostoevsky is notorious for dropping hints via the names of his characters — applied nominative determinism — and this one’s name means something like “supremacy”.

Or as another famous book about demons once put it:

I am the spirit that negates And rightly so, for all that comes to be Deserves to perish wretchedly; 'Twere better nothing would begin. Thus everything that your terms, sin, Destruction, evil represent -- That is my proper element.

Or maybe society is already correcting itself on this point. Many like to make fun of the “fragility” and “snowflake” nature of Gen Z, and I’ve argued before that these critics miss the point that they’re actually being “flexed on” (in the parlance of our times) because loudly asserting an exaggerated harm is a power move (think: upper class women in an honor culture claiming to feel threatened, and how that’s actually itself a threat).

But here’s a different take on it: maybe “trauma” as it’s popularly conceptualized is actually modernity groping its way back to a porous understanding of the self! We no longer believe in spirits or curses, but our psyches are self-evidently susceptible to immaterial external influence, so we create a new concept that aligns empirical psychic porosity with the dominant metaphysical and ideological currents.

I had a long debate with myself on whether to include either of those links. Do I really want to expose more people to an infohazard? Ultimately I decided to do it because this stuff is already so widespread. In both cases I’ve linked to a page that links to the subject matter in question rather than linking directly, so you have one more chance to bail out.

I’m told that the internet jargon for this is an “unbuilt trope.”

Dostoevsky positions a former serf as the defender of “Holy Russia,” Orwell suggests that if there is hope it lies in the proles, Bismarck believed the poor would serve as a reactionary bulwark against liberalism, and MAGA believes that various dispossessed and subaltern groups will keep America great. Are they all correct? No. They’re all wrong. The lower classes have no special compass for political or religious truth, they’re just almost definitionally slightly behind the times. When an egregore is rapidly accumulating strength, they’re likely to oppose it out of inertia, but they’re as vulnerable as anyone to its blandishments, and will just as vigorously defend the new thing once it has taken over.

Look, I have a lot of sympathy for these guys. Like the Russian radicals of the 1870s, they correctly observe that there’s something insane and rotten about our society, but unlike those radicals they’re attracted to something that’s really out there and really true and good. “Fake it til you make it” is not the worst strategy ever invented for securing a mature and authentic faith in a supreme being. But once you’re in that state, there’s a clock running, your time is limited, there are other things out there in the night, attracted by the smell of lost and receptive souls.

This is one of the best book reviews I’ve ever read.

It's a good review, but you're very unfair to Fathers and Sons, which is nowhere close to wish fulfillment you describe. You say it's about zoomers learning to accept their boomer parents? Please! Bazarov, (the book's hero), scorns his own loving parents, romantically humiliates and then shoots the narrator's uncle, and finally dies of a self-inflicted wound. You make it sound like an after-school special. It's true that Arkady (the narrator) ends on good terms with his family, but not because he's realized they're hip after all. Rather, he finds he can't stomach the cruelty of Bazarov towards their parents' generation, for whom he has always harbored great affection. The point of the novel is not that Bazarov is wrong and Arkady is right, or reverse -- it's that Arkady's maturation forces him to recognize that he will never be as bold or exciting as Bazarov, and that any attempt to emulate Bazarov will always come off as ugly and inauthentic. Even with his downfall, at the novel's end it's clear that the future belongs to the Bazarovs of the world, and not the Arkadys. Arkady will live a nice life on his farm, but he will never become a figure of importance.

The Faust passage is wonderful. I want to read Faust now.