REVIEW: Flying Blind, by Peter Robison

Flying Blind: The 737 MAX and the Fall of Boeing, Peter Robison (Doubleday, 2021).

Such a frustrating book! Such a missed opportunity! The premise is great: “how a subtle change in corporate culture led inexorably to planes falling out of the sky and the deaths of 346 people.” Alas, the execution is not there, and it becomes increasingly clear as you read this that Peter Robison has no idea how to trace the chain of causality. So he panics, flounders, falls back on the hoariest and most shopworn investigative journalist clichés ([gasp] “did you know there was regulatory capture?” Buddy, when is there not regulatory capture?). It’s very sad, because he’s done his homework and interviewed a bazillion people, and because now that he’s ruined this topic nobody else is going to get a publisher’s advance to write this book the way it should have been done. Well, can we do better?

Let’s start where Robison does, at the beginning. Boeing was once a young startup, founded by the eccentric heir to a timber fortune. Through a mixture of luck, derring-do, and frequent cash injections from its wealthy patron, it managed to avoid bankruptcy long enough for World War II to begin, at which point the military contracts started rolling in. Along the way, it developed an engineer-dominated, technically perfectionist, highly deliberative corporate culture. At one time, you could have summed it up by saying it was the Google of its time, but alas there are problems with that analogy these days. Maybe we should say it was the “circa 2005 Google” of its time.

There’s a lot to love about an engineer-dominated corporate culture. For starters, it has a tendency to overengineer things, and when those things are metal coffins with hundreds of thousands of interacting components, filled with people and screaming through the air at hundreds of miles an hour, maybe overengineering isn’t so bad. These cultures also tend to be pretty innovative, and sure enough Boeing invented the modern jet airliner and then revolutionized it several times.

But there are also downsides. As any Googler will tell you, these companies usually have a lot of fat to trim. Some of what looks like economic inefficiency is actually vital seed corn for the innovations of the future, but some of it is also just inefficiency, because nobody looks at the books, because it isn’t that kind of company. Likewise, being highly deliberative about everything can lead to some really smart decision making and avoidance of group think, but it can also be a cover for laziness or for an odium theologicum that ensures nothing ever gets done. Smart managers steeped in this sort of culture can usually do a decent job of sorting the good from the bad, but only if they can last, because you see there’s a third problem, which is that almost everybody involved is a quokka.

Engineers, being a subspecies of nerds, are bad at politics. In 1996, Boeing did something very stupid and acquired a company that was good at politics. McDonnell Douglas, another airplane maker, wasn’t the best at making airplanes, but was very good at lobbying congress and at impressing Wall Street analysts. Boeing took over the company, but pretty much everybody agrees that when the dust had settled it was actually McDonnell Douglas that had taken over Boeing. One senior Boeing leader lamented that the McDonnell Douglas executives were like “hunter killer assassins”. No, sorry bro, I don’t think they were actually that scary, you were just a quokka.

Anyway, the hunter killer assassins ran amok: purging rivals, selling off assets, pushing through stock buybacks, and outsourcing or subcontracting everything that wasn’t nailed down. They had a fanaticism for capital efficiency that rose to the level of a monomania,1 which maybe wasn’t the best fit for an airplane manufacturer. And slowly but surely, everything went off the rails. Innovation stopped, the culture withered, and eventually planes started falling out of the sky. And now the big question, the question Robison just can’t figure out. Why?

A lot of thinkfluencers will describe technology as an “ecosystem” without grappling with the full implications of that term. Most often when they say it they’re referring to a cluster of consumer-facing businesses that rent space or other capabilities from a “platform” provider, like apps on an App Store. But that isn’t an ecosystem, that’s a shopping mall. Real ecosystems have energy and nutrient flow both up and down the food chain, as well as laterally; they have vast swarms of bottom feeders, fungi, and other detritivores that recycle matter through decomposition and make its constituents bioavailable once more; they also have a constant source of energy input (usually the sun) to make up for the constant entropic drag that would otherwise grind things to a halt. One of the great discoveries of modern ecology is that apex predators, macrofauna, the plants and animals we notice and admire are perched precariously atop a vast network of invisible supports. A tiger is the temporary result of too many worms gathering in one place.

Technology is also an ecosystem, not the way bluechecks talk about it, but in this more profound sense. A Boeing or a Google is like a tiger: the highly-visible culmination of a vast subterranean drama. Turn over a spade and you’ll find them — the suppliers and subcontractors, investor networks, tooling manufacturers, feeder universities, advisors, researchers, shipping and packaging experts, friendly bankers and government officials, producers of upstream technological inputs, and a vast collection of lower-tier companies in related markets that act like an economic flywheel, absorbing and releasing excess labor as the economy shudders through its fits and starts.

In nature, it’s energy and nutrients that move through the food webs. Here their analogues are capital and knowledge. It’s hard to miss the money sloshing back and forth — world-changing companies are nurtured through their awkward adolescence by sophisticated and patient pools of capital, and the high-flying champions of those companies become the next generation’s venture investors after cashing out. Harder to see but even more influential is the vast economic dark matter made up of professionals who struck it rich enough to live comfortably but not rich enough to fly private. These unobtrusive capitalists are the first to hear through professional whispernets that so-and-so has quit his job to work on such-and-such. Since they’re still in the rat-race, they can have an informed opinion on the caliber both of the idea and of the team around it, and are usually the early champions of the most unusual and speculative ventures. And finally, money sloshes around between the companies themselves through a complicated network of deals, joint ventures, and strategic investments.

The money is more visible, but the way knowledge moves is more important. Part of it is academic, propositional knowledge or technical data whose discovery is accelerated when a dozen different teams are on its scent, sometimes racing each other to the prize, sometimes egging each other on and celebrating each others’ victories. But the bulk of what makes this ecosystem hum, the true currency that drives nearly every barter or exchange, is practical, process knowledge of the sort that 莊子 first described and Michael Oakeshott later re-popularized for our benighted and ignorant age. What makes process knowledge unusual is that by its very nature it cannot be separated from people, cannot be digitized or divorced or attached to an email. It is at once the nous of a technological ecosystem and the thing that makes it fundamentally illegible — an immaterial, intangible essence that inheres only in individuals, like a mind or a soul.

Dan Wang, in his wonderful essay on how technology grows, describes process knowledge as the sine qua non of industrial capitalism, more fundamental than the machines and factories that everybody sees:

The tools and IP held by these firms are easy to observe. I think that the process knowledge they possess is even more important. The process knowledge can also be referred to as technical and industrial expertise; in the case of semiconductors, that includes knowledge of how to store wafers, how to enter a clean room, how much electric current should be used at different stages of the fab process, and countless other things. This kind of knowledge is won by experience. Anyone with detailed instructions but no experience actually fabricating chips is likely to make a mess.

I believe that technology ultimately progresses because of people and the deepening of the process knowledge they possess. I see the creation of new tools and IP as certifications that we’ve accumulated process knowledge. Instead of seeing tools and IP as the ultimate ends of technological progress, I’d like to view them as milestones in the training of better scientists, engineers, and technicians.

The accumulated process knowledge plus capital allows the semiconductor companies to continue to produce ever-more sophisticated chips. […] It’s not just about the tools, which any sufficiently-capitalized firm can buy; or the blueprints, which are hard to follow without experience of what went into codifying them.

Process knowledge lives in people, grows when people interact with other people, and spreads around when skilled individuals relocate between cities or companies. But this also means it can wither and die, can be lost forever, either when old workers shuffle off to the Big Open Plan Office in the Sky, or when an ecosystem no longer has the energy or complexity to sustain a critical mass of skilled workers in a particular vocation. Some East Asian societies have gone to extreme lengths to retain process knowledge, for instance by deliberately demolishing and rebuilding a temple every 20 years.

In fact this is far from the most extreme thing East Asian societies have done to retain the process knowledge that lives within their workers! There are some components of an ecosystem, whether natural or technological, that are especially important keystone species. In the technological case, these species can be unprofitable at the current scale of an ecosystem, or inefficient, or they might not make economic sense until one or more of their customers exist, but those customers might not be able to exist until the keystone species does. Venture capital is very practiced at solving this kind of Catch-22, but in the East Asian economic boom it was national governments that actively sheltered keystone industries until they could get their footing, thus making entire ecosystems possible. A wonderful book about this is Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works, but if you can’t read it, read Byrne Hobart’s thorough review instead.

Process knowledge is so powerful, the ecosystem it enables so vital, it can break the assumptions of Ricardo’s theory of trade. Steve Keen has a perceptive essay about how the naive Ricardian analysis treats all capital stock as fungible and neglects the existence of specialized machinery and infrastructure. But naive defenders of trade liberalization often make an exactly analogous error with respect to the other factor of production — labor. Workers are not an undifferentiated lump, they are people with skills, connections, and expertise locked up in their heads. When a high-skill industry moves offshore, the community of experts around it begins to break up, which can cripple adjacent industries, stymie insights and breakthroughs, and make it almost impossible to bring that industry back.

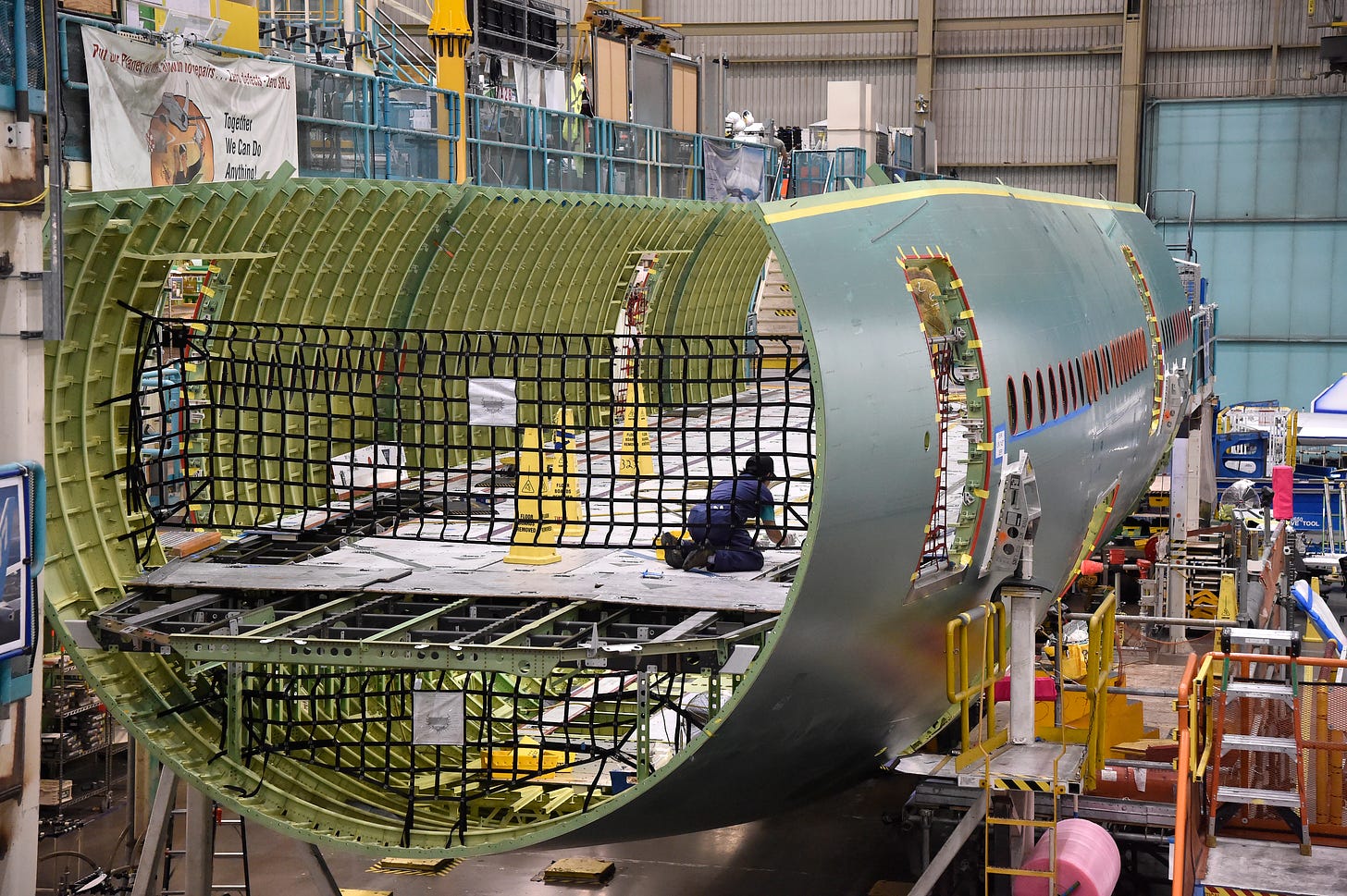

As at the macro level, so at the micro level. Those McDonnell Douglas managers probably really did find some non-core job functions that could be more efficiently subcontracted away. But every such small gain in economic efficiency came with a hidden cost. For every component whose production was outsourced away, Boeing lost irreplaceable information about its “implementation details” — tolerances, design history, manufacturing approach, undocumented capabilities or limitations.

Any engineer worth his salt can feel this ground shifting under him, and will react by piling additional details into the specification for the part that he once would have taken for granted. Indeed Robison notes that one specification document for an electronic part in the 777 that used to be 20 pages long ballooned to 2,500 pages after the outsourcing blitzkrieg. But no amount of such specification can catch every last nuance of a component’s behavior. If you want something to be exactly so, at some point you need to either make it yourself or be friends and colleagues with the person who makes it. Small wonder that top engineering companies like SpaceX, Apple, and Google frequently reject the false economies of outsourcing and bring the design and manufacture of their dependencies fully in-house.2

Mis-specification is far from the only danger of taking the engineers charged with making a component and the engineers charged with using it, and putting them under different roofs. Conversations around the water-cooler, clichéd as that idea might be, are a constant source of serendipitous discoveries across the interfaces between teams. “Oh, the reason you wanted it to have property X is because you wanted to do Y? But there’s a much easier way to accomplish Y!” Or even more importantly: “Yikes, I can see why you thought that, but in this case property X won’t actually enable Y, we need to redesign this.” Nobody gets credit for these conversations, they don’t appear on anybody’s budget, they don’t show up as a line item on anyone’s P&L statement, yet there are few things more important. Their invisible presence is felt by senior leadership and program managers as “luck” — serendipitous redesigns that come out of nowhere, or disastrous misunderstandings that aren’t caught until the last minute.

The water cooler is also a back channel of last resort when vital information isn’t spreading any other way, due to organizational dysfunction, empire building by middle management, or just simple carelessness. Collegial relationships, where you’re all in it together and all have a common share price, reduce the psychological and emotional barriers to “betraying” your team or department by engaging in this sort of horizontal whistle-blowing. Conversely, the commercial relationship between a company and its subcontractor is governed by documents that will eventually be adjudicated in an adversarial legal system. This massively increases the personal and organizational stakes of any information leak.

Subcontracted relationships like this are implicated in several steps of the failure cascade that led to Boeing airliners falling out of the sky. Key examples include responsibilities for writing the manual for the new aircraft and the entire organization of test pilots, both of which had once been core parts of Boeing’s commercial airliner division, both of which were out-sourced to third parties by the hunter killer assassins, and both of which had independently discovered the fatal flaw in the 737 MAX-8 but were unable to communicate effectively back to the design staff.

Boeing says they’re very sorry about all of this. The flaw in the airliners has been patched, yet nothing fundamental about their company organization has changed. Try as I might, I can’t get too mad at them, because process knowledge once lost can be extraordinarily hard to regain. It’s not clear that they could switch back to a vertically-integrated culture of engineering excellence even if they wanted to.

What keeps me up worrying isn’t the long-haul flight on a Boeing airliner I’m making tonight, it’s every other company in America. You see, it isn’t just economic and legal alignment that are necessary for the healthy spread of process knowledge, you also need physical proximity. It isn’t a coincidence that nearly every high-tech industry — software, semiconductors, cars, electronics, biotech, machine parts — tends to cluster into geographic concentrations. The spontaneous lunches, chance encounters in the hallway, and (yes) chats around the water cooler are a load-bearing element in the architecture of all of these industries.

For the last 3 years, American corporations have been running a radical social experiment in the form of remote work. Like offshoring and subcontracting, remote work offers a one-time boost in economic efficiency in exchange for permanently damaging the growth and diffusion of process knowledge. Talk to workers who love remote employment, and you hear a lot of: “I’m just as productive at my [narrowly defined] job”, with scant recognition of the positive externalities their presence in the office might bring.

Maybe they’re right. Maybe the cafeteria conversations, the glancing over a newbies’ shoulder and gently correcting his technique, the zero-friction questions and suggestions and learning by watching others at work, maybe none of it matters. At Boeing, it took years before the invisible unraveling of their engineering community produced visible effects — cost overruns, schedule slips, design errors, manufacturing defects, and finally a deadly catastrophe. The thing about mortgaging the future for short-term benefit is that everything looks great until everything suddenly looks terrible. But maybe it’ll be fine in this case. I guess we’ll find out.

This is how you know this story took place in an era of high interest rates!

These companies are frequently teased for “not invented here”-syndrome by people who work at objectively more mediocre companies.

"One of the great discoveries of modern ecology is that apex predators, macrofauna, the plants and animals we notice and admire are perched precariously atop a vast network of invisible supports. A tiger is the temporary result of too many worms gathering in one place."

Hot dang do I wish I could write like this.

Minor nitpick: you have your specification page-lengths for the 777 and 787 reversed. It was 2500 pages on the 777, and just 20 pages on the later 787 (the problem was that Boeing massively under-specified a lot of components, leading to coordination issues down the line).