Home Comforts: The Art and Science of Keeping House, Cheryl Mendelson (Scribner, 1999).

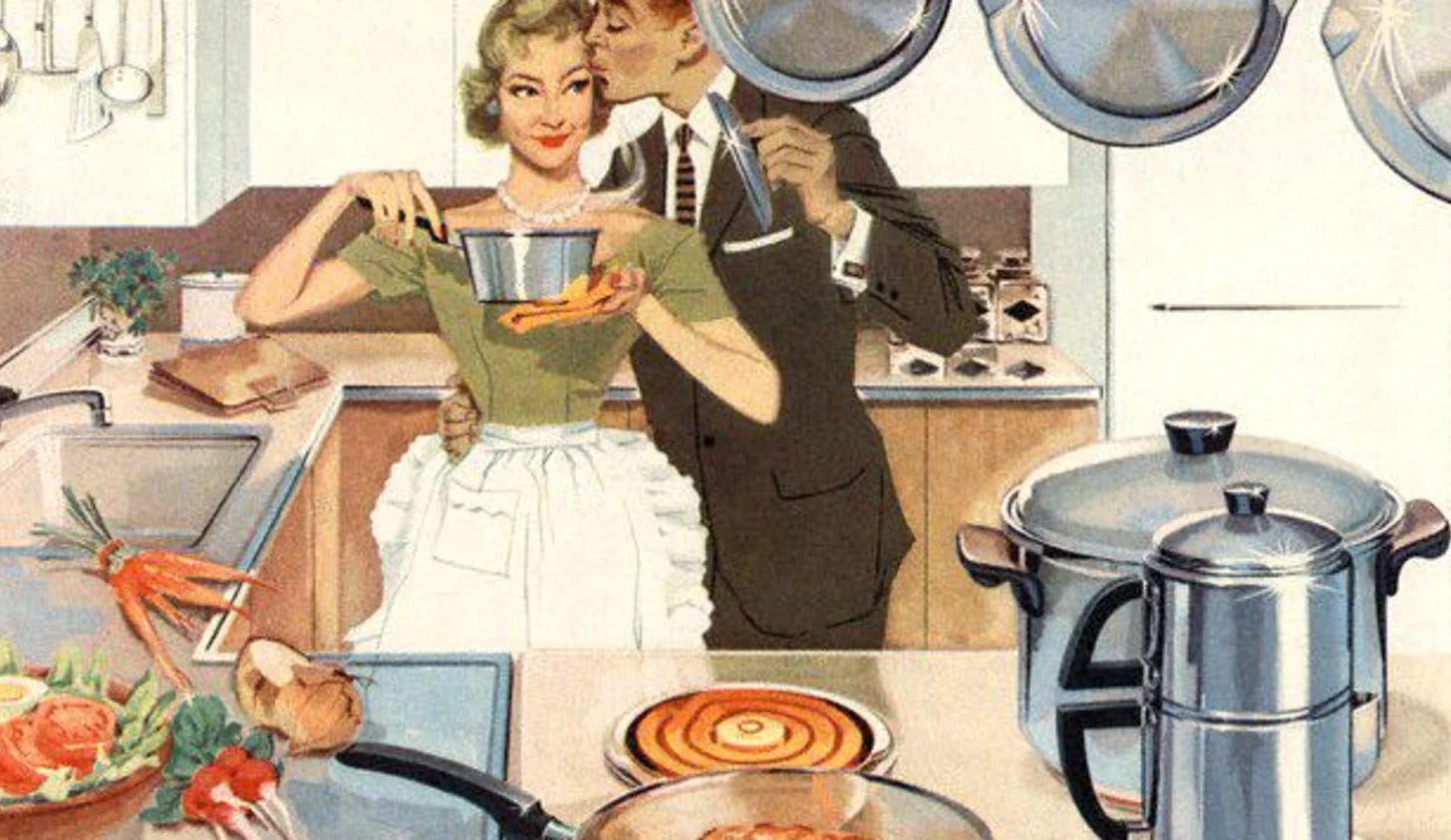

A couple of months ago, a nice young man asked me to write something about being a SAHM. I’ve been home with my kids since my eldest was born more than a decade ago and I seemed (he said) to be pretty happy. Yet somehow, none of the nice young women he knew considered it a live option for their futures. It wasn’t that they’d considered it and decided it wasn’t for them; they just seemed to assume it couldn’t possibly be satisfying. I, obviously, think it is. What’s up with that?

Well, I am lazy, so I went looking for a good link to send him. Surely so much has been written about motherhood — usually on websites with graphics featuring that one font that shows up on everything marketed to women — that someone, somewhere, had already written what I wanted to say. But it turns out that mommy blogs are written for people who are already someone’s mommy, and all you can find elsewhere is endless rehashing of the economic tradeoffs — given the price of daycare, can you afford to work? given the foregone career progression and retirement savings, can you afford not to? And that’s fine, but I wasn’t looking for a case that being home is better. I just wanted the argument that it’s good. I was looking for a positive vision of why an intelligent, accomplished young woman might want to devote herself to the care of her home and family. So I decided I would have to write it myself.

It’s not a complicated case. It really just boils down to the simple claim that it is good and valuable work to make a home for your family, whether or not it includes children. But “simple” doesn’t mean “uncontroversial.” After all, isn’t housework basically drudgery? Isn’t having someone else to scrub the toilets and change the diapers what we have an open border for? Isn’t it practically an insult to suggest that a smart, capable young woman consign herself for a period of years to nothing more intellectually stimulating than vacuuming Cheerio crumbs and picking up someone else’s discarded socks? For this you went to college? (Because, of course, the office job you would otherwise be working contains no drudgery.) Yet here I was, taking the counterintuitive position that domestic labor is good, actually, and I couldn’t quite figure out how to articulate it beyond something like, “You know how SWPL bougies get about cooking? That but for laundry.”

And then a few weeks ago I picked up my copy of Home Comforts and read the opening sentences: “When you keep house, you use your head, your heart, and your hands together to create a home—the place where you live the most important parts of your private life. Housekeeping is an art: it combines intuition and physical skill to create comfort, health, beauty, order, and safety.” And I thought: oh.

Home Comforts is a massive doorstopper of a tome (906 pages in my edition), and most of the page count is devoted to an encyclopedia of housekeeping topics, from interpreting laundry care labels to food safety to the proper way to vacuum upholstery. It’s less useful as a reference work now that Google can answer your questions more rapidly than an index (“do I really have to dry clean it if it says ‘dry clean only’?”), but the real pleasure of it was always Cheryl Mendelson’s defense of keeping house. It’s not a necessary evil, she says; it’s affirmatively good, it’s valuable work of which someone who went to Harvard Law School can be really proud. (When she first published it more than twenty years ago, she had left a legal and academic career for writing and housewifery; she has since returned to occasional adjuncting in moral philosophy at Barnard.)1 And so here I found my case already half-made for me:

Housekeeping creates cleanliness, order, regularity, beauty, the conditions for health and safety, and a good place to do and feel all the things you wish and need to do and feel in your home. Whether you live alone or with a spouse, parents, and ten children, it is your housekeeping that makes your home alive, that turns it into a small society in its own right, a vital place with its own ways and rhythms, the place where you can be more yourself than you can be anywhere else.

What a gift to give to yourself and the people you love. It’s not only the maintenance of physical order, the tidying of surfaces and washing of dishes and changing of sheets; a well-kept home is also a vital source of psychic and even moral order. Think how stressful it is to be hungry and trying to figure out what you can eat. Think how much calmer and more pleasant you can be to the people around you when you’re not juggling a dozen projects at once, when you haven’t run out of toilet paper and you have milk for your coffee and you know where to find the receipt you need. Think how comforted and secure you feel when someone (perhaps someone else, perhaps Past You) has taken a moment to think of your needs, even in something so small as making sure you have clean underwear. And then expand this to the tiny, helpless people who rely on you to create the structure that allows them to venture out, explore, and return to a place of comfort and safety.

The small society of your home, like all societies, has a culture. It has values and things “we don’t do,” ways of living that encode tacit knowledge and convey unarticulated principles. If you live alone this may just be an unexamined outgrowth of personality and habit (though consider how many people have tried to live a different way, wanting something better for themselves even if they can’t make the change stick), but even a pair of adults is engaged in a collaborative cultural process. Do we watch TV at dinner? (Do we even consider the possibility that we might?) How do we speak to each other, what do we do together, what do we do for one other? And so, obviously, when you add children to the family, the demands on the family culture grow. They have to be taught care and consideration for others, respect for their environment, love of God (or veneration of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights or a personal relationship with the preserved corpse of Jeremy Bentham, you do you), and they’ll only learn these things if they see them in their home. Anything they don't see at home, or don't see often enough, will eventually be displaced in favor of its mass culture equivalent by sheer osmosis. Grown-ups can have the odd evening where, okay, we might gotten fast food on DoorDash and eaten it on the couch while scrolling Twitter in total silence, but that’s not who we are. Children, on the other hand, are the ratchet effect incarnate and can support far fewer of these exceptions, and a necessary reset (say, when Mom and Dad finally recover from the flu and the endless My Little Pony supply is cut off) can be exceptionally painful. The creation and maintenance of a culture is work, and like all the other work it expands exponentially when children are involved.

What mothers have always known, and social scientists have recently begun presenting as a shocking fact, that a great deal of the work involved in making a home isn’t the direct labor of shopping, cleaning, cooking, removing the toddler from the washing machine, &c., but the planning and organizing that comes before it: which stores do you have to visit and in what order to get everything you need, how long has it been since the bath towels were changed (and for that matter since the children bathed), is that kale in the crisper drawer going to survive another couple of days or should you throw it into the pasta sauce tonight. My favorite Shirley Jackson work isn’t any of her horror stories but the screamingly funny Life Among the Savages, where she gives a perfect example:

I believe that all women, but especially housewives, tend to think in lists; I have always believed, against all opposition, that women think in logical sequence, but it was not until I came to empty the pockets of my light summer coat that year that I realized how thoroughly the housekeeping mind falls into the list pattern, how basically the idea of a series of items, following one another docilely, forms the only possible reasonable approach to life if you have to live it with a home and a husband and children, none of whom would dream of following one another docilely. What started me thinking about it was the little slips of paper I found in the pockets of my light summer coat, one beginning “cereal, shoes to shop, bread, cheese, peanut butter, evening paper, doz doughnuts, CALL PICTURE.” I showed this list to my husband, and he read it twice and said it didn’t make any sense. When I told him that it made perfect sense because it followed my route up one side of the main street of our town and down the other side—I have to buy the cereal at a special store, because that’s the only one which carries the kind the children like—he said then what did CALL PICTURE mean? and when I explained that it meant I must call the picture-framer before I started out and was in big letters because if I took the list out in the store and found I had forgotten to call the picture-framer I would then have to stop in and see him… The other list I found in my summer coat pocket started out “summer coat to clnrs.”2

Our fourth grader can pack school lunches; the first grader can move a load of laundry from washer to dryer. My job to make sure we have the cold cuts for their sandwiches, and laundry gets done before we run out of clean underwear, and there are dollar bills for when the Tooth Fairy is expected, and the baby’s nap schedule has been adjusted to the microsecond to accommodate both today’s preschool early dismissal and the regular school pickup, and the filters on the air vents have been changed so we don’t get allergies, and the city has been called because according to my records we already paid that water bill (oh, my job is also keeping the records), and…

Of course, these are things every household has to do (or pay the costs, in money, time, or stress, for not doing), and without children it’s not that hard to fit them into evenings, weekends, or lunch breaks. But once you have kids, with their illnesses and their messes and their clothes they’ve ripped or outgrown (not to mention all the fun parts, like the books to read to them and the games to play with them and the swings to push them on), you have both more to do and less time to do it in. And I don’t mean to say you can’t have a job and wedge all these other things into whatever crevices you can find, many people do, but the whole point of being home is so you don’t have to. Go to the hardware store for that new hose valve on a Tuesday morning when it’s just you and the contractors, prune the viburnums while the baby chases his ball around the yard, make dinner during naptime so you aren’t spending the witching hour settling sibling disputes from the stove. Your spare capacity creates flexibility and space for flourishing, not just for you (because there’s definitely at least forty hours of work to do, but it’s not all nine-to-five) but for your entire family. Me being home has meant my family could move to the opposite coast for work, and then back (for different work). It’s meant that in February 2020 we could take our first grader out of the school we didn’t much like anyway and spend a year building Assyrian siege equipment out of LEGOs and memorizing the Roman emperors instead of putting her on endless Zoom calls. It’s meant that I can be actively involved in the school we found later (which we love), or make food for a sick friend, or manage testing and therapy for what blessedly turned out to a mild and easily-treated developmental delay — without the added stress completely upending the equilibrium of our household. And of critical importance to you if you’re reading this, it’s meant that my husband and I have the free time to read books and write this Substack.

This is why I don’t like the term “stay-at-home mom.” It always reads to me as implying that childcare is the only reason not to have a paying job, and while that’s not entirely wrong — small children do need someone to watch them, and a household without children probably doesn’t have enough work to occupy a person for the entire day — it misses the point. Wrangling small children is only part of the work of caring for your home and your family. You could, if you wanted, substitute in a good nanny, one who would educate, entertain, and enrich your children (but won’t do laundry or cook or mail packages, nannies have a code), and even then all the other work would remain — with the added burden of managing the performance of an unusually intimate employee. The point of being home isn’t just the kids (although the kids are wonderful!), it’s the kids and everything else. And so I generally prefer to call myself a housewife.3

Of course it can be lonely, and it can be boring, especially when you only have one baby.4 But I have been reliably informed that every field of human endeavor is occasionally lonely and/or boring. Certainly every job I've ever had was! And anyway, it’s nice to do these things for yourself. Being home is, as Mendelson puts it, “among the most thoroughly pleasant, significant, and least alienated forms of work that many of us will encounter even if we are blessed with work outside the home that we like.” Hard work is always more rewarding when you know you’ll capture every drop of the value you create. One of my fondest memories is of that first April of the pandemic, when everything was closed but we hadn’t yet realized what a slog it was all going to be, and I spent what had been our summer camp budget on an enormous jungle gym complete with crow’s nest observation tower.5 We spent more than a week building it together: the children ferried bolts and screws, I sorted the pieces of pre-drilled lumber and held them in place, and my husband climbed the growing structure to get everything attached. It wasn’t terribly well machined, and several times we had to stop because I wasn’t very good at plugging in the spare battery so it actually charged, but the whole thing was tremendous fun. We had made something impressively large, something we knew we would all enjoy for years, and we had done it together.

And this, I think, is one part of why those nice young women can’t imagine themselves staying home: it’s a way of structuring your life and dividing the work of the family that only makes sense with a partner. You become one half of a whole, and that’s tremendously difficult to envision without knowing the particular person who would be the other half. Can you trust that when he comes home to your reasonably tidy house, with its homemade meals and its functioning appliances and its happy children, he will really respect and value your contribution to the mutual work of making a life together? Contemporary discussions of the “mental load” seethe with anger at the husbands who just don’t see everything their wives are doing behind the scenes to make everything tick; being home can mean your family explicitly recognizing the mental Sherpa’s vital role, but if done wrong it can also mean a soul-crushing disregard. And this is only compounded by the other thing preventing young women from considering housewifery: being at home is low status.

Cheryl Mendelson knows this: “No one meeting me for the first time would suspect that I squander my time knitting or my mental reserves remembering household facts such as the date when the carpets and mattresses were last rotated,” she writes in her first chapter, titled “My Secret Life”:

Without thinking much about it, I knew I would not want this information about me to get around. After all, I belong to the first generation of women who worked more than they stayed home. We knew that no judge would credit the legal briefs of a housewife, no university would give tenure to one, no corporation would promote one, and no one who mattered would talk to one at a party.

Taking a few years off from an already-successful career to have babies is sometimes respectable as an strangely atavistic sort of hobby, like bow-hunting or through-hiking the Appalachian Trail, but that lasts no longer than when the youngest child enters kindergarten. Making a lifestyle of it, being a housewife rather than a temporarily-staying-at-home mom, is regarded as dangerously retrograde and/or white trash. And to that I say: who cares? Your concern is for your own small society, your own family culture. Do you want to be valley people? Do you want to marry someone who wants to be valley people?

You don’t have to forgo paid employment to find value in caring for your home and family, just as you don’t have to keep house the way Cheryl Mendelson does. (I have a cupboard full of jam made by a dear friend who has both a baby and a full-time job; I have never in my life ironed a bedsheet and I don’t intend to start now.) But you should, at least, recognize the deep satisfaction and deeper freedom that come from a well-kept home, and you should think seriously about how you can secure that for your family.

Her husband Edward Mendelson is the Lionel Trilling Professor in the Humanities at Columbia, as well as literary executor of W. H. Auden’s estate, and according to her chapter on the care of books “will lend a book only when he has privately steeled himself to the certainty of never seeing it again, and even keeps a shadow library of cheap paperback editions that he loans out instead of his good hardback copies.”

I have lists exactly like this. They live in my Notes app and are interspersed with a catalog of interesting people from Tudor England, measurements for rugs I mean to buy one day if I see a good deal at an estate sale or thrift shop, books I needed to order when I homeschooled my oldest child three years ago, and an inventory of our chest freezer.

Not least because it’s awfully fun when someone at a cocktail party opens with “so, what do you do?” If you say you stay home with your kids they’ll tell you it’s the most important job in the world and look for someone more interesting to talk to, but if you cheerfully reply “I’m a housewife!” I find you will usually have surprised them enough that in the brief moment of confusion you can jump in with something you’d actually like to talk about.

I read this essay back when my oldest was a baby and thought it seemed crazy, but in fact it is entirely correct.

This was all before supply chain issues were invented, of course; for a long time you couldn’t get one of these for love or money and now that they’re back on the market they cost twice what I paid for it.

Alexi and I try to make a habit of telling each other about the smaller, hidden bits of maintenance (e.g. the perennial wet swiffering of the floor, erased by the time he's home; unpacking and rearranging the boxes in the storage room). Because it would be easy to not notice them, and we try to tell and receive them not as a "Because you never notice" and more as a "I know you wouldn't want to miss the chance to be happy about this" and that's mostly where we land!

I love this book! I bought it when it came out in 1999 and it’s on my shelf right now.

As I’ve suffered through a debilitating illness over the last year, I’ve been grateful for the slack in our household system—slack which is only available because my husband and I made the choice for me not to work outside the home. Giving ourselves that space is, in my opinion, another good reason for one person to opt out of a “typical” employment track.