REVIEW: Sea People, by Christina Thompson

Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia, Christina Thompson (HarperCollins, 2019).

Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum is a 19th century physician’s cabinet of curiosities with a 21st century museum layered on top. Its dark wood panelling and glass-fronted cases contain, among other highlights, a collection of one hundred and thirty nine human skulls (each labeled with name, age, occupation, and cause of death) and the preserved conjoined liver of Chang and Eng Bunker, with fascinating if gruesome explanations of the anatomical oddities displayed. But beside the accumulated specimens is modern commentary on the history and culture of the doctors who diagnosed and treated them. The museum contains both the thing itself, our best current understanding of the thing, and something of the story of how we used to understand it and have come to do so differently.

Sea People is a little like that.

Christina Thompson layers the story of Polynesian expansion, itself a fascinating tale still half-shrouded in prehistory, with the story of European attempts to understand it. She guides the reader through the early attempts to translate Polynesian legend into a history with names and dates, nineteenth century theories that the Polynesians were really Aryans (read: Proto-Indo-Europeans), and social-scientific somatological surveys, down to the evidence of more modern radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis. In the end, though, it all comes down to a single question: how did a single group of Neolithic people manage to settle every single habitable rock between New Guinea and the Galápagos, an area of more than ten million square miles in the middle of the Pacific Ocean?

The Polynesians did it without maps or compasses, without writing, without metal. Europeans explorers with all of these things spent hundreds of years confined by currents and winds to a narrow path across the vast expanse of the Pacific — nearly all of them, beginning with Magellan in 1521, encountered the Tuamotus, but the Chatham Islands weren’t discovered until 1791 — and yet every time Europeans limped into port they found the Polynesians already there.

And the Polynesians clearly did it so quickly, and so recently, that when in 1769 a Tahitian stepped ashore in New Zealand his language was instantly understandable to the waiting Māori. This was more than 2500 miles from his home, something on the order of the distance from Moscow to Madrid; while at some point the pre-Italic family that gave rise to Latin and thence the Romance languages must have been mutually intelligible with the pre-Slavic languages that gave us Russian, Hernán Cortés certainly wouldn’t have been understood if he’d somehow wound up in the court of Ivan the Terrible.

So how did the Polynesians do it? And when, and why, and why did they stop?

Thompson’s vivid, detailed prose explains the constraints of land and sea so clearly that the islands themselves become characters as individual as any human in the book. The Marquesas are high islands, their “peaks shrouded in mist, their folds buried in greenery, their flanks rising dramatically from the sea, they have a brooding, prehistoric beauty,” while the Tuamotus are low islands, from the air “bright circlets of green and white floating like diadems in a sapphire sea” but “really a necklace of inlets…strung along a circle of reef,” where

…it becomes breathtakingly clear that the ground beneath your feet is not really land in the way that most people understand it, but rather the tip of an undersea world that has temporarily emerged from the ocean. The real action, the real landscape, is all of water: the great rollers that boom and crash on the reef, the rush and suck of the tide through the passes, the breathtaking hues of lagoon.

She is clearly very fond of the Polynesians (her husband is Māori), but her recounting of the islanders’ encounters with Europeans are generous and sympathetic to both sides despite their mutual incomprehension and occasional violence. And yet that incomprehension is less than it might seem, for the Polynesians were also the scions of a people who had climbed aboard their own ships and sailed off into unknown waters in search of new lands. Far from the stereotypical first contact story of natives carried off against their will,1 many of the Polynesians were eager to join the European voyages. Within a few decades of contact, Thompson writes, "Polynesians of all stripes would be crisscrossing the ocean...signing on as deckhands on ships out of Sydney, San Francisco, Nantucket, Honolulu."2 Pioneering ethnographer Horatio Hale described them as "cosmopolites by natural feeling," with "a disposition for enterprise and bold adventure." The most dramatic individual in Thompson's book, the Tahitian who landed in New Zealand with James Cook's first expedition, was a perfect example. His name was Tupaia.

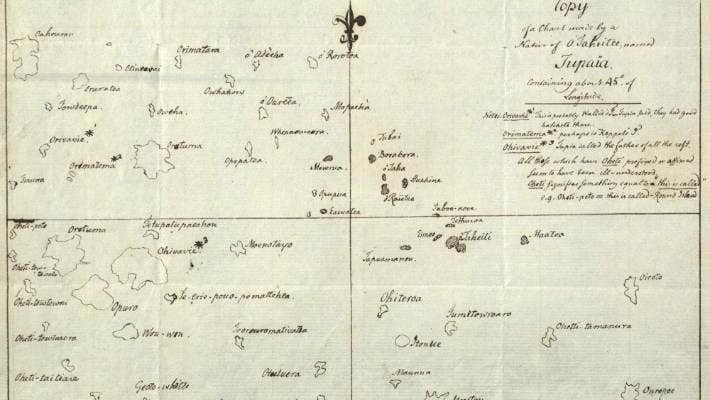

Tupaia was a Tahitian tahua’a (Māori tohunga, Hawaiian kahuna — linguistic drift really hadn’t gotten far!), a member of a priestly adept class that Thompson explains would be responsible for “maintaining not only the history and genealogy of the ruling family to which he was attached, including their sacred rituals and rites, but all the esoteric knowledge of the people in general” in spheres of human endeavor we would categorize as including “cosmology, politics, history, medicine, geography, astronomy, meteorology, and navigation, all of which, in a world with no clear division between natural and supernatural, were inextricably entangled with religion.” As important to our story as this practical expertise, though, was Tupaia’s adventurous spirit. The Endeavour had come to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus, but the British admiralty wasn’t about to waste a perfectly good South Seas trip on purely scientific work when they could also send along sealed secret orders to search for terra australis incognita. So when Cook was preparing to leave for the leg of his journey that would ultimately include mapping New Zealand and discovering the east coast of Australia, Tupaia asked to come along. He offered his own expansive knowledge of the seas, which included details of the locations, reefs, and harbors, of at least fifty islands covering more than two thousand miles of ocean. Once on board the Endeavour, Tupaia was deeply involved in piloting and navigation and an invaluable advisor in the expedition’s interactions with the Polynesians they encountered. He was also eager to explore his new companions’ culture: we have records of his conversations with the passengers, a number of his paintings of life in Tahiti, New Zealand, and Australia, and his map.

Before he was given command of the Endeavour, James Cook’s only claim to fame was as a meticulous surveyor of Newfoundland whose maps were an order of magnitude more detailed than those of his contemporaries. Tupaia, for his part, had been experimenting with European-style maps of the reefs and inlets of his home island (not, in fact, Tahiti — he was from neighboring Ra’iatea but had been driven away by invading Bora Borans) since before he joined the expedition. Perhaps it was inevitable that, during the two months the Endeavour doglegged generally southwest from Tahiti in search of the “unknown southern land,” the two men should have produced such a map. But it is a fascinating document less for its accuracy than for its attempt to leap a radical epistemological gap.

Polynesians had no tradition of cartography (nor of naturalistic representation in visual art, which didn’t seem to stop Tupaia either), but the disconnect went well beyond that. The Polynesians simply had no tradition at all of the kind of imagined impersonal viewpoint that European-style nautical charts — or rationalist analysis more generally — depend upon. Their directional vocabulary was based not on east or west, but on whether something was towards or away from the sea (if the speaker was on land) or its relation to the wind (if at sea). Their navigational system was distinctly relational: not a description of the objective location of some island in space, but an account of the stars, winds, currents, cloud formations, and sea marks one would encounter on the way from one island to another. Distance was given in experiential terms: Tupaia told Cook that the Tongan archipelago was ten days away from Tahiti, but Tahiti was thirty days away from the Tongan archipelago. (This makes perfect sense if you remember which way the wind blows, but it’s not how a European would phrase things.) Two hundred years later, English doctor-sailor David Lewis encountered the same issue when he tried to piece together the “ancient sea-lore of Oceania”: as part of a discussion with a navigator from the Caroline Islands, he drew a diagram to illustrate a point and found that his interlocutor simply didn’t understand what he was trying to communicate. The Caroline Islanders use an especially complicated and abstract system called etak to track their journeys, but like all traditional Polynesian navigators employ a “star compass” based on the rising and setting points of particular stars relative to the boat in order to navigate.3 The boat is the center of a vast semi-sphere of sky, a fixed point in the world, with the stars and islands moving around it. For the European navigator, the geographic reference point is up in the sky looking down, while for the Polynesian navigator it is a “real point of view in real local space.”

At this point, we should confront the fact that Tupaia’s map is, well…wrong. Thompson writes:

[M]any of the islands on the chart, including some that would appear from their names to belong to the Samoan, Tongan, Cook, and Austral archipelagoes, are wrongly positioned — north when they should be south, southwest when they should be northwest, or, most confusingly, split between north and south when they should be together in one place or the other.

A number of explanations have been proffered for this (Horatio Hale suggested that Cook attempted to fill in the islands he knew personally but had the map upside down), but they all boil down to the claim that Tupaia was making a different kind of map. If he was using not the European model of objective, quantitative, universal measurement but rather the egocentric model of the star compass, Thompson offers, “some thirty-three of the islands…can be identified in terms of plotting diagrams using five different islands of departure.” Perhaps Tupaia was clustering them according to how they could be reached using certain sets of bearings. But then why adopt the mathematical grid model of European maps in the first place? Whether a true failure of understanding or “simply” incomplete translation from one conceptual system to another, Tupaia’s map is a striking example of the incommensurability of these wildly different lifeworlds.

Modern attempts to recreate the techniques of ancient Polynesian navigation confirm this difficulty. David Lewis was thrilled to discover that the knowledge remained, as he put it, in “a mosaic of fragments…only waiting to be put together,” but he himself remained the rankest amateur — a cataloguer but not a practitioner. When the replica double-hulled canoe Hōkūleʻa made her maiden voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti, the voyagers had to import a Caroline Islander to navigate. It was not for nearly another generation that someone originally raised in the objective, analytical European tradition was able to immerse himself deeply enough in traditional navigational practices to make the journey without instruments. Like the Israelites wandering in the desert, it took a great deal of time for people to become accustomed to thinking a different way.

This is not to say that we can’t wrap our heads around other ways of seeing and understanding — Thompson herself does a beautiful job of explaining the underlying assumptions of the Polynesian lifeworld — but we can’t fully know and inhabit them without leaving some of our own behind. One might be tempted to ask which of these two ways of seeing is better, but better at what? The Polynesian conceptual framework was manifestly tremendously effective for navigating the ocean with neolithic technology. The European conceptual framework was just as clearly effective for developing ships, maps, and satellites that have made it possible to navigate without what anthropologist Thomas Gladwin describes as the Puluwatan’s experience of “the sum of input from such disparate sources as stars, swells, and birds being processed through training and practice into a confident awareness of precisely where they were at any one time.” That sense of world unity, whoever, is absent. After all, analysis (ἀνα- + λύω) means literally to unravel or break up: our culture’s analytical approach has given us a great deal, but it has taken something too.

In the end, it turns out the question we began with — how did the Polynesians get there? — was answered by the Polynesians themselves. They were all extremely clear, from the very beginning, that their ancestors had come in boats, on purpose, from elsewhere (a place they universally called some variant on “Hawaiki”). Radiocarbon dating and DNA evidence have given us the path and the timeline. What they can’t tell us is why the expansion began and why it stopped.

We know the ancestral Polynesians and their advanced sailing techniques moved rapidly through the inhabited islands of the western Pacific and settled in Tonga and Samoa, where they remained for almost two thousand years before their expansion into the rest of the Polynesian triangle. We know they were able to find their way from one tiny speck of land in a mostly-empty sea to the next not only because David Lewis and a host of “experimental archeologists” were able to reconstruct and reenact their journeys but because their descendants can be found on every habitable rock and atoll in the South Pacific (and evidence of past visitors or residents can be found in many of the uninhabitable ones). And yet by the time they encountered Europeans, the epic voyaging phase of Polynesian life was over. They traveled between islands and even archipelagos in the denser parts of the Polynesian Triangle, but of the fifty islands Tupaia listed, he had visited only half a dozen. In the century between Abel Tasman’s original encounter with the Māori of New Zealand and their rediscovery on Cook’s first voyage, they had abandoned their double-hulled ocean-going canoes for hundred-foot single-hulled waka taua optimized for littoral raiding. The heroic expeditions to far-off lands were no more — or, at least, they would never again be repeated from within the Polynesian lifeworld. The Hawaiian, Samoan, and Māori deckhands who filled the ships of the nineteenth century, and Tupaia himself, were echoes of their ancestors’ expeditions, but they were only echoes.

Thompson suggests that the Polynesian expansion from Tonga and Samoa might have been driven by climate instability, or an increased emphasis on personal genealogy and founder-ancestor veneration, but underlying it all is the implication that there was some vital spark was struck around the year 1000 — and that it was guttering even before an out-of-context problem appeared on the horizon. However well-suited Polynesian technology may have been for their physical environment, and it was clearly extremely adaptive, they were nevertheless displaced as masters of the South Seas by other men — men who also had ships but who had other, very different, ways of seeing and understanding the world. The wave of Polynesian expansion lasted only a few hundred years; it left its mark on the landscape and its people’s outlook, but it ebbed quickly into admiring legend of achievements no one even tried to match.

So ask yourself: what has your culture done lately?

One of the best-known is “Squanto,” the Patuxet Indian who helped the Pilgrims through their first winter, who famously greeted them in the English he had learned after being kidnapped, sold into slavery, and eventually ransomed by charitable monks. Less well-known is the fact that the key agricultural innovation every schoolchild knows he taught the starving Englishmen — planting their corn with a fish head to serve as fertilizer — was in fact a European technique he learned during his time in England.

The “kanaka” of the sea shanty “John Kanakanaka” is Hawaiian for “man” and was a frequently used by fellow sailors as a substitute for difficult-to-pronounce Polynesian names.

Thompson’s account of David Lewis’s navigational research and experiments is simply charming. Here he is sailing with a man from Puluwat in the Caroline Islands:

On his first night of sailing with Hipour, Lewis observed how he steered first toward the setting Pleiades, then, as they became masked by clouds, how he kept the rising Great Bear to one side, in line with part of the rigging, then held the Pole Star in line with the edge of the wheelhouse, while keeping “the sinking Pollux fine on the starboard bow.” At one point, Lewis wrote, “a strange star appeared at which I stared in surprise; but Hipour merely grinned and remarked, unexpectedly in English, ‘Satellite.’”