REVIEW: The Domestic Revolution, by Ruth Goodman

The Domestic Revolution: How the Introduction of Coal into Victorian Homes Changed Everything, Ruth Goodman (Liveright, 2021).1

Note: We usually avoid publishing reviews on similar topics too close together, but I was reading this book, and writing this review, at the same time as my husband was reading and reviewing Energy and Civilization and we kept interrupting each other to share interesting facts about coal. They were, however, very different sorts of facts, these are very different reviews, and I thought the contrast was a fun #thetwogenders moment.

Last spring, my oldest daughter and I set out to tame our blackberry thicket. Half a dozen bushes, each with a decade’s worth of dead canes, had come with our house, and we were determined to make them accessible to hungry children. (Do you have any idea how much berries cost at the grocery store, even in the height of summer? Do you have an idea how many hours of peaceful book-reading you can stitch together out of the time your kids are hunting for fruit in their own yard? It’s a win-win.) But after we’d cut down all the dead canes, I explained that we also needed to shorten the living ones, especially the second-year canes that would be bearing fruit later in the summer. At this point, scratched and sweaty from our work, she balked: was Mom trying to deprive the children of their rightful blackberries? But I explained that on blackberries, like most woody plants, the terminal bud suppresses growth from all lower buds; removing it makes them all grow new shoots, each of which will have flowers and eventually fruit. Cutting back the canes in March means more berries in July. At which point I could see a light dawning in her eyes as she exclaimed, “Oh! We’re memorizing the Parable of the True Vine in school but I never knew why Jesus says pruning the vines makes more fruit…”

It’s pretty trite by now to point out that Biblical metaphors that would have made perfect sense for an agricultural society are opaque to a modern audience for whom vineyards are about the tasting room and trimming your wick extends the burn time of your favorite scented candle. There’s probably whole books out there exploring the material culture of first century Judaea to provide context to the New Testament.2 But at least pruning is a “known unknown”: John 15:2 jumps out as confusing, and anyone who does a little gardening can figure out the answer. Plenty of things aren’t like that at all. Even today, few people record the mundane details of their daily lives; in the days before social media and widespread literacy it was even more dramatic, so anyone who wants to know how our ancestors cleaned, or slept, or ate has to go poking through the interstices of the historical record in search of the answers — which means they need to recognize that there’s a question there in the first place. When they don’t, we end up with whole swathes of the past we can’t really understand because we’re unfamiliar with the way their inhabitants interacted with the physical world.

The Domestic Revolution is about one of these “unknown unknowns,” the early modern English transition from burning wood to coal in the home, and Ruth Goodman may be the only person in four hundred years who could have written it. With exactly the kind of obsessive attention to getting it right that I can really respect, she turned an increasingly intensive Tudor reënactment hobby into a decades-long career as a “freelance historian,” rediscovering as many domestic details of Tudor-era life as possible and consulting for museums and costume dramas. Her work reminds me of the recreations of ancient Polynesian navigational techniques, a combination of research and practical experiments aimed at contextualizing what got remembered or written down, so of course I would love it. (A Psmith review of her How To Be a Tudor is forthcoming.) She’s also starred in a number of TV shows where she and her colleagues live and work for an extended time in period environs, wearing period costume and using period technology,3 and because she was so unusually familiar with running a home fired by wood — “I have probably cooked more meals over a wood fire than I have over gas or electric cookers,” she writes — she immediately noticed the differences when she lived with a coal-burning iron range to film Victorian Farm. A coal-fired home required changes to nearly all parts of daily life, changes that people used to central heating would never think to look for. But once Goodman points them out, you can trace the radiating consequences of these changes almost everywhere.

The English switched from burning wood to burning coal earlier and more thoroughly than anywhere else in the world, and it began in London. Fueling the city with wood had become difficult as far back as the late thirteenth century, when firewood prices nearly doubled over the course of a decade or two, and when the population finally recovered from the rolling crises of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the situation became dire once again. Wood requires a lot of land to produce, but it’s bulky and difficult to transport by cart: by the 1570s the court of Elizabeth I found it cheapest to buy firewood that had been floated more than a hundred miles down the Thames. Coal, by contrast, could be mined with relative ease from naturally-draining seams near Newcastle-upon-Tyne and sailed right down the eastern coast of the island to a London dock. It already had been at a small scale throughout the Middle Ages, largely to fuel smithies and lime-burners, but in the generation between 1570 and Elizabeth’s death in 1603 the city had almost entirely switched to burning coal. (It had also ballooned from 80,000 to 200,000 inhabitants in the same time, largely enabled by the cheaper fuel.) By 1700, Britain was burning more coal than wood; by 1900, 95% of all households were coal-burning, a figure North America would never match. Of course the coal trade itself had consequences — Goodman suggests that the regular Newcastle run was key in training up sailors who could join the growing Royal Navy or take on trans-Atlantic voyages — and it certainly strengthened trade networks, but most of The Domestic Revolution is driven by the differences in the materials themselves.

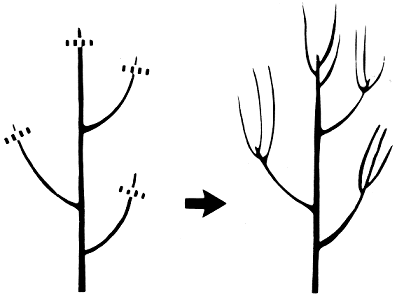

The most interesting part of the book to me, a person who is passionately interested in all of human history right up until about 1600, were the details of woodland management under the wood-burning regime. I had, for instance, always assumed that early modern “woodcutters” like Hansel and Gretel’s father were basically lumberjacks chopping down full-grown trees, but actually most trees aren’t killed by removing their trunks. Instead, the stump (or roots, depending on the species) will send up new, branchless shoots, which can be harvested when they reach their desired diameter — anywhere from a year or two for whippy shoots suitable for weaving baskets or fences to seven years for firewood, or even longer if you want thick ash or oak poles for construction. This procedure, called coppicing, also extends the life of the tree indefinitely: an ash tree might live for two hundred years, but there are coppiced ash stools in England that predate the Norman Conquest. (My ignorance here wasn’t entirely chronological provincialism: the pines and other conifers that make up most North American timberland can’t be coppiced.)4 The downside to coppicing is that the new shoots are very attractive to livestock, so trees can also be pollarded — like a coppice, but six or eight feet up the trunk,5 quite a dramatic photo here — which is harder to harvest but means you can combine timber and pasture. This made pollarded “wood pasture” a particularly appealing option for common land, where multiple people had legal rights to its use.6 The woodcutters of the Grimms’ tales probably had a number of fenced coppiced patches they would harvest in rotation, ideally one fell for each year of growth it took to produce wood of the desired size, though a poor man without the upfront capital to support planting the right kind of trees could make do with whatever nature gave him.

There’s plenty more, of course: Goodman goes into great but fascinating detail about the ways different woods behave on the fire (hazel gets going quickly, which is nice for starting a fire or for frying, but oak has staying power; ash is the best of both worlds), the ways you can change the shape and character of your fire depending on what you’re cooking, and the behavior of other regional sorts of fuel like peat (from bogs) and gorse (from heathland). But most of the book is devoted to the differences between burning wood and burning coal, of which there are three big ones: the flame, the heat, and the smoke. Dealing with each one forced people to make obvious practical changes to their daily lives, and in turn each of those changes had second- and third-order consequences that contributed to the profound transformations of the modern period.

The most obvious difference is the fire itself. The flames of wood fires merge together to form a pyramid or spire shape, perfect for setting your pot over: the flames will curl around its nicely rounded bottom to heat it rapidly. Coal, on the other hand, forms “a series of smaller, lower, hotter and bluer flames, spaced across the upper surface of the bed of embers,” suitable for a large flat-bottomed pot. More importantly, though, burning coal requires a great deal more airflow: a coal fire on the ground is rapidly smothered by its own buildup of ash and clinker (and of course it doesn’t come in nice long straight bits for you to build a pyramid out of). The obvious solution is the grate, a metal basket that lifts the coal off the ground, letting the debris fall away rather than clogging the gaps between coals, and drawing cold air into the fire to fuel its combustion. This confines the fire to one spot, which may not seem like a big deal (especially for people who are used to cooking on stoves with burners of fixed sizes) but is actually quite a dramatic change. As Goodman explains, one of the main features of cooking on a wood fire is the ease with which you can change its size and shape:

You can spread them out or concentrate them, funnel them into long thin trenches or rake them into wide circles. You can easily divide a big fire into several small separate fires or combine small fires into one. You can build a big ring of fire around a particularly large pot stood at one end of the hearth while a smaller, slower central fire is burning in the middle and a ring of little pots is simmering away at the far end. You can scrape out a pile of burning embers to pop beneath a gridiron when there is a bit of toasting to do, brushing the embers back into the main fire when the job is done.

In other words, the enormous fireplaces you may have seen in historical kitchens aren’t evidence of equally enormous fires; they were used for lots of different fires of varying sizes, to cook lots of different dishes at the same time. The iron grate for coal, on the other hand, is a fixed size and shape, like a modern burner — though unlike a modern burner the heat is not adjustable. The only thing you can do, really, is put your pot on the grate or take it off.

The most common everyday sort of meal in wood-burning Britain was what we might call pottage or frumenty, a thick moist dish in which whole grains or pulses are brought to a boil and then simmered until as much liquid as possible has been absorbed. Think risotto but with less stirring. The simplest version was very simple indeed — wheat or barley or peas cooked in water with whatever fresh vegetables or herbs were available — but if you had the means you could add anything that was in season: meat, fish, butter or cheese, milk or cream, eggs, and even delicacies like sugar, almonds, or imported dried fruits.7 In fact most medieval dishes were thick and sticky, exactly the sort of thing I like to give my toddlers because it stays on even the most inexpertly wielded spoon, and they’re extremely well-adapted to cooking over wood. Just get your pot boiling over a big fire, then as the flames die down your dinner will simmer nicely. You’ll have to stir it, of course, to keep it from sticking to the pot, but you have to come back anyway to feed the fire. You can cook like this over coal, but it’s difficult: a coal fire stays hot much longer, so moderating the temperature of your frumenty requires constantly putting your pot on the grate and taking it off again. It’s far simpler to just add more liquid and let it all boil merrily away, with the added bonus that the wetter dish needs much less stirring to keep it from sticking. With the switch to coal, boiled dinners — soups, meats, puddings, and eventually potatoes — became the quintessentially English foods.8

A coal fire also burns much hotter, and with more acidic fumes, than a wood fire. Pots that worked well enough for wood — typically brass, either thin beaten-brass or thicker cast-brass — degrade rapidly over coal, and people increasingly switched to iron, which takes longer to heat but lasts much better. At the beginning of the shift to coal, the only option for pots was wrought iron — nearly pure elemental iron, wrought (archaic past tense of “worked,” as in “what hath God wrought”) with hammer and anvil, a labor-intensive process. But since the advent of the blast furnace in the late fifteenth century, there was a better, cheaper material available: cast iron.9 It was already being used for firebacks, rollers for crushing malt, and so forth, but English foundries were substantially behind those of the continent when it came to casting techniques in brass and were entirely unprepared to make iron pots with any sort of efficiency. The innovator here was Abraham Darby, who in 1707 filed a patent for a dramatically improved method of casting metal for pots — and also, incidentally, used a coal-fired blast furnace to smelt the iron. This turned out to be the key: a charcoal-fueled blast furnace, which is what people had been using up to then, makes white cast iron, a metal too brittle to be cast into nicely curved shapes like a pot. Smelting with coal produces gray cast iron, which includes silicon in the metal’s structure and works much better for casting complicated shapes like, say, parts for a steam engine. Coal-smelted iron would be the key material of the Industrial Revolution, but the economic incentive for its original development was the early modern market for pots, kettles, and grates suitable for cooking over the heat and fumes of a coal fire.10

In Ruth Goodman’s telling, though, the greatest difference between coal and wood fires is the smoke. Smoke isn’t something we think much about these days: on the rare occasions I’m around a fire at all, I’m either outdoors (where the smoke dissipates rapidly except for a pleasant lingering aroma on my jacket) or in front of a fireplace with a good chimney that draws the smoke up and out of the house. However, a chimney also draws about 70% of the fire’s heat — not a problem if you’re in a centrally-heated modern home and enjoying the fire for ✨ambience✨, but a serious issue if it’s the main thing between your family and the Little Ice Age outdoors. Accordingly, premodern English homes didn’t have chimneys: the fire sat in a central hearth in the middle of the room, radiating heat in all directions, and the smoke slowly dissipated out of the unglazed windows and through the thatch of the roof. Goodman describes practical considerations of living with woodsmoke that never occurred to me:

In the relatively still milieu of an interior space, wood smoke creates a distinct and visible horizon, below which the air is fairly clear and above which asphyxiation is a real possibility. The height of this horizon line is critical to living without a chimney. The exact dynamics vary from building to building and from hour to hour as the weather outside changes. Winds can cause cross-draughts that stir things up; doors and shutters opening and closing can buffet smoke in various directions. … From my experiences managing fires in a multitude of buildings in many different weather conditions, I can attest to the annoyance of a small change in the angle of a propped-open door, the opening of a shutter or the shifting of a piece of furniture that you had placed just so to quiet the air. And as for people standing in doorways, don’t get me started.

One obvious adaptation was to live life low to the ground. On a warm day the smoke horizon might be relatively high, but on a cold damp one (of which, you may be aware, England has quite a lot) smoke hovers low enough that even sitting in a tall chair might well put your head right up into it. Far better to sit on a low stool, or, better yet, a nice soft insulating layer of rushes on the floor.

Chimneys did exist before the transition to coal, but given the cost of masonry and the additional fuel expenses, they were typically found only in the very wealthiest homes. Everyone else lived with a central hearth and if they could afford it added smoke management systems to their homes piecemeal. Among the available solutions were the reredos (a short half-height wall against which the fire was built and which would counteract drafts from doorways), the smoke hood (rather like our modern cooktop vent hood but without the fan, allowing some of the smoke to rise out of the living space without creating a draw on the heat), or the smoke bay (a method of constructing an upstairs room over only part of the downstairs that still allowed smoke to rise and dissipate through the roof). Wood smoke management was mostly a question of avoiding too great a concentration in places you wanted your face to be. The switch to coal changed this, though, because coal smoke is frankly foul stuff. It hangs lower than wood smoke, in part because it cools faster, and it’s full of sulfur compounds that combine with the water in your eyes and lungs to create a mild sulfuric acid; when your eyes water from the irritation, the stinging only gets worse. Burning coal in an unvented central hearth would have been painful and choking. If you already had one of the interim smoke management techniques of the wood-burning period — especially the smoke hood — you would have found adopting coal more appealing, but really, if you burned coal, you wanted a chimney. You probably already wanted a chimney, though; they had been a status symbol for centuries.

And indeed, chimneys went up all over London; their main disadvantage, aside from the cost of a major home renovation, had been the way they drew away the heat along with the smoke, but a coal fire’s greater energy output made that less of an issue. The other downside of the chimney’s draw, though, is the draft it creates at ground level. Again, this isn’t terribly noticeable today because most of us don’t spend a lot of time sitting in front of the fireplace (or indeed, sitting on the floor at all, unless we have small children), but pay attention next time you’re by an indoor wood fire and you will notice a flow of cold air for the first inch or two off the ground. All of a sudden, instead of putting your mattress directly on the drafty floor, you wanted a bedstead to lift it up — and a nice tall chair to sit on, and a table to pull your chair up to as well. There were further practical differences, too: because a chimney has to be built into a wall, it can’t heat as large an area as a central fire. This incentivized smaller rooms, which were further enabled by the fact that a coal fire can burn much longer without tending than a wood fire. A gentleman doesn’t have much use for small study where he can retreat to be alone with his books and papers if a servant is popping in every ten minutes to stir up the fire, but if the coals in the grate will burn for an hour or two untended he can have some real privacy. The premodern wood-burning home was a large open space where many members of the household, both masters and servants, went about their daily tasks; the coal-burning home gradually became a collection of smaller, furniture-filled spaces that individuals or small groups used for specific purposes. Nowhere is this shift more evident than in the word “hall,” which transitions from referring to something like Heorot to being a mere corridor between rooms.

But coal smoke had dramatic implications for daily life even beyond the ways it reshaped domestic architecture, because in addition to being acrid it’s filthy. Here, once again, Goodman’s time running a household with these technologies pays off, because she can speak from experience:

So, standing in my coal-fired kitchen for the first time, I was feeling confident. Surely, I thought, the Victorian regime would be somewhere halfway between the Tudor and the modern. Dirt was just dirt, after all, and sweeping was just sweeping, even if the style of brushes had changed a little in the course of five hundred years. Washing-up with soap was not so very different from washing-up with liquid detergent, and adding soap and hot water to the old laundry method of bashing the living daylights out of clothes must, I imagined, make it a little easier, dissolving dirt and stains all the more quickly. How wrong could I have been.

Well, it turned out that the methods and technologies necessary for cleaning a coal-burning home were fundamentally different from those for a wood-burning one. Foremost, the volume of work — and the intensity of that work — were much, much greater.

The fundamental problem is that coal soot is greasy. Unlike wood soot, which is easily swept away, it sticks: industrial cities of the Victorian era were famously covered in the residue of coal fires, and with anything but the most efficient of chimney designs (not perfected until the early twentieth century), the same thing also happens to your interior. Imagine the sort of sticky film that settles on everything if you fry on the stove without a sufficient vent hood, then make it black and use it to heat not just your food but your entire house; I’m shuddering just thinking about it. A 1661 pamphlet lamented coal smoke’s “superinducing a sooty Crust or Furr upon all that it lights, spoyling the moveables, tarnishing the Plate, Gildings and Furniture, and corroding the very Iron-bars and hardest Stones with those piercing and acrimonious Spirits which accompany its Sulphure.” To clean up from coal smoke, you need soap.

“Coal needs soap?” you may say, suspiciously. “Did they…not use soap before?” But no, they (mostly) didn’t, a fact that (like the famous “Queen Elizabeth bathed once a month whether she needed it or not” line) has led to the medieval and early modern eras’ entirely undeserved reputation for dirtiness. They didn’t use soap, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t clean; instead, they mostly swept ash, dust, and dirt from their houses with a variety of brushes and brooms (often made of broom) and scoured their dishes with sand. Sand-scouring is very simple: you simply dampen a cloth, dip it in a little sand, and use it to scrub your dish before rinsing the dirty sand away. The process does an excellent job of removing any burnt-on residue, and has the added advantage of removed a micro-layer of your material to reveal a new sterile surface. It’s probably better than soap at cleaning the grain of wood, which is what most serving and eating dishes were made of at the time, and it’s also very effective at removing the poisonous verdigris that can build up on pots made from copper alloys like brass or bronze when they’re exposed to acids like vinegar. Perhaps more importantly, in an era where every joule of energy is labor-intensive to obtain, it works very well with cold water.

The sand can also absorb grease, though a bit of grease can actually be good for wood or iron (I wash my wooden cutting boards and my cast-iron skillet with soap and water,11 but I also regularly oil them). Still, too much grease is unsanitary and, frankly, gross, which premodern people recognized as much as we do, and particularly greasy dishes, like dirty clothes, might also be cleaned with wood ash. Depending on the kind of wood you've been burning, your ashes will contain up to 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH), better known as lye, which reacts with your grease to create a soap. (The word potassium actually derives from “pot ash,” the ash from under your pot.) Literally all you have to do to clean this way is dump a handful of ashes and some water into your greasy pot and swoosh it around a bit with a cloth; the conversion to soap is very inefficient (though if you warm it a little over the fire it works better), but if your household runs on wood you’ll never be short of ashes. As wood-burning vanished, though, it made more sense to buy soap produced industrially through essentially the same process (though with slightly more refined ingredients for greater efficiency) and to use it for everything.

Washing greasy dishes with soap rather than ash was a matter of what supplies were available; cleaning your house with soap rather than a brush was an unavoidable fact of coal smoke. Goodman explains that “wood ash also flies up and out into the room, but it is not sticky and tends to fall out of the air and settle quickly. It is easy to dust and sweep away. A brush or broom can deal with the dirt of a wood fire in a fairly quick and simple operation. If you try the same method with coal smuts, you will do little more than smear the stuff about.” This simple fact changed interior decoration for good: gone were the untreated wood trims and elaborate wall-hangings — “[a] tapestry that might have been expected to last generations with a simple routine of brushing could be utterly ruined in just a decade around coal fires” — and anything else that couldn’t withstand regular scrubbing with soap and water. In their place were oil-based paints and wallpaper, both of which persist in our model of “traditional” home decor, as indeed do the blue and white Chinese-inspired glazed ceramics that became popular in the 17th century and are still going strong (at least in my house). They’re beautiful, but they would never have taken off in the era of scouring with sand; it would destroy the finish.

But more important than what and how you were cleaning was the sheer volume of the cleaning. “I believe,” Goodman writes towards the end of the book, “there is vastly more domestic work involved in running a coal home in comparison to running a wood one.” The example of laundry is particularly dramatic, and her account is extensive enough that I’ll just tell you to read the book, but it goes well beyond that:

It is not merely that the smuts and dust of coal are dirty in themselves. Coal smuts weld themselves to all other forms of dirt. Flies and other insects get entrapped in it, as does fluff from clothing and hair from people and animals. to thoroughly clear a room of cobwebs, fluff, dust, hair and mud in a simply furnished wood-burning home is the work of half an hour; to do so in a coal-burning home — and achieve a similar standard of cleanliness — takes twice as long, even when armed with soap, flannels and mops.

And here, really, is why Ruth Goodman is the only person who could have written this book: she may be the only person who has done any substantial amount of domestic labor under both systems who could write. Like, at all. Not that there weren’t intelligent and educated women (and it was women doing all this) in early modern London, but female literacy was typically confined to classes where the women weren’t doing their own housework, and by the time writing about keeping house was commonplace, the labor-intensive regime of coal and soap was so thoroughly established that no one had a basis for comparison.

The transition may also have driven broader cultural shifts. In 1523, Fitzherbert’s Boke of Husbandrie gave a list of a housewife’s jobs (“What warkes a wyfe shulde do in generall”) that included the household’s cooking, cleaning, laundry, and childcare, all of which are typically part of modern housewifery, but also milking cows, taking grain to the miller, malting barley, making butter and cheese, raising pigs and poultry, gardening, growing hemp and flax and then spinning it, weaving, winnowing grain, making hay, cutting grain, selling her produce at market — and, as necessary, helping her husband to fill the dungcart, plow the fields, or load hay. Roles were still highly gendered, but compared to eighteenth and nineteenth century household manuals this is a remarkable amount of time spent out of the house, and the difference holds even when you compare the work hired maids were doing in both periods. Around the time of the advent of coal, though, our descriptions of women’s work increasingly portray it as contained within the walls of the home — or, at most, in the dairy or the poultry yard. Of course social transformations are never monocausal, and the increasing specialization and mechanization that moved some production out of the household probably nudged things along, but Goodman suggests that “the additional demands of running a coal-fired household might have also helped push the idea that a woman’s place is within the home.” After all, if your cleaning takes twice as long, there’s simply less time available for all that agricultural labor and small-scale commerce.

The Domestic Revolution is a fascinating tour of the ways relatively minor changes snowball, changing the way people interact with the material world and with one another, but it’s also a tremendous pleasure for its lucid, practical explanations of how these things actually work. Goodman is deeply familiar with her tools and materials in a way that’s quite unusual today. Of course anyone who really makes things will have this familiarity — ask a software engineer about programming languages or his favorite text editor — but in most walks of life actually making things has become increasingly optional. Of the objects I interact with on a daily basis, the only ones I can really be said to have made (my kids don’t count) are the things I cook and the chairs I refinished and upholstered.12 Beyond that there’s the garden I planted with seeds and perennials I bought at a nursery, the furniture I assembled out of pieces some nice Swedish man machined for me, and the various bits of plumbing I’ve swapped out, but none of that is really “making” so much as it is “assembling things other people have made.” It’s mostly the productive equivalent of last mile delivery — nothing to sneeze at, but a far cry from the sort of deep involvement with the material world that was common only a few centuries ago.

This makes perfect sense, of course: I don’t have a deep and intimate knowledge of these things because I don’t need one. Still, though, it’s important to have a certain very basic familiarity with how the things around you work — enough, say, to know what to Google when something breaks and how to put the results into practice, or to turn fifteen feet of arching blackberry cane into an actual bush — because it gives you power over your world. The particular powers don’t really matter (it’s easy enough to pay someone else to fix your plumbing or grow your berries); the key is the patterns of thought they engender. There are, for example, apparently some enormous number of people who don’t change the batteries in their beeping smoke detectors. I have no idea whether it’s drug-induced apathy, ignorance of how things work (in the same way that drilling a hole in your wall to hang something seems scary if you don’t know that your wall is a lie just painted drywall in front of empty space between the studs), or simply a pathological lack of personal agency, but it’s hard to believe you can change anything dissatisfactory about your life if you can’t change a 9V battery.

Making and doing things, even when you don’t have to, is practice in believing that you can change your own world. It’s weightlifting for agency. You can outsource the making of your physical world, but social worlds — the arrangement of your family life, your personal relationships, the organizations and institutions you’re involved in — must be created by the participants themselves. A good society would be one where the default “builder-grade” scripts lead to human flourishing, but unfortunately that isn’t ours, so you have to be able to decide on your own changes. Start practicing now: find one little thing about your physical environment that annoys you and fix it. Put the new toilet paper roll actually on the holder. Replace the burned-out lightbulb. Hang the artwork that’s listing drunkenly against the wall. Pull some weeds. And then, once you've warmed up a little bit, go and make something new.

This is a bad subtitle and it should feel bad; the book is mostly about the early modern period and barely touches on the Victorians.

Are they any good? Should I read them? I’ve mentally plotted out a structure for one of my own, where each chapter is themed around the main image of one of the parables — oil, wine, seeds, fish, sheep, cloth, salt — and explores all the practicalities: the wine chapter would cover viticulture techniques but also land ownership (were the vintners usually tenants? what did their workforce look like?), seeds would cover how grain was planted, harvested, milled, and cooked, etc. The only problem is that I don’t actually know anything about any of this.

Several of them are streaming on Amazon Prime; I don’t much TV, but I did watch Tudor Monastery Farm with my kids and we all loved it.

Some firs can be regrown in a related practice called “stump culture,” which is particularly common on Christmas tree farms, but it’s much more labor-intensive than coppicing.

If you live in the southern United States, you’ve probably seen pollarded crape myrtles.

Contrary to the impression you may have gotten from the so-called tragedy of the commons, the historical English commons had extremely clearly delineated legal rights. More importantly, these rights all had fabulous names like turbary (the right to cut turves for fuel), piscary (the right to fish), and pannage (the right to let your pigs feed in the woods). I’m also a big fan of the terminology of medieval and early modern tolls, like murage (charged for bringing goods within the walls), pontage (for using a bridge), and pavage (using roads). Since the right to charge these tolls was granted to towns and cities individually, a journey of any length was probably an obnoxious mess of fees (Napoleon had a point with the whole “regulating everything” bit), but you can’t help feeling that “value added tax” is pretty boring by comparison. I suggest “emprowerage,” from the Anglo-Norman emprower (which via Middle English “emprowement” gives us “improvement”) as a much more euphonious name for the VAT. Obviously sales tax should “sellage.” I can do this all day.

We’re used to thinking of plants as being seasonal, but until quite recently animal products were seasonal too: chickens won’t lay in the winter without artificial lighting, cows stop giving milk when their calves reach a certain age, and generally one would only slaughter an animal for its meat at the right time of year. Geese, for instance, were typically eaten either as a “green goose,” brought up on summer grasses and slaughtered as soon as it reached adult size around the middle of July, or a “stubble goose,” fattened again on what remained in the fields after harvest and eaten for Michaelmas (in late September). Feeding a goose all autumn and half the winter only to eat it for Christmas would have been silly.

It’s also typical of New England, which makes sense; the New Englanders by and large came from East Anglia, which is right on the Newcastle-London coal route and a region that adopted coal cookery relatively early.

Brief ferrous metallurgy digression: aside from the rare, relatively pure iron found in meteors, all iron found in nature is in the form of ores like haematite, where the iron bound up with oxygen and other impurities like silicon and phosphorus (“slag”). Getting the iron out of the ore requires adding carbon (for the oxygen to bond with) and heat (to fuel the chemical reaction): Fe2O3 + C + slag → Fe + CO2 + slag. Before the adoption of the blast furnace, European iron came from bloomeries: basically a chimney full of fuel hot enough to cause a reduction reaction when ore is added to the top, removing the oxygen from the ore but leaving behind a mass of mixed iron and slag called a bloom. The bloom would then be heated and beaten and heated and beaten — the hot metal sticks together while the slag crumbles and breaks off — to leave behind a lump of nearly pure iron. (If you managed the temperature of your bloomery just right you could incorporate some of the carbon into the iron itself, producing steel, but this was difficult to manage and carbon was usually added to the iron afterwards to make things like armor and swords.) In a blast furnace, by contrast, the fuel and ore were mixed together and powerful blasts of air were forced through as the material moved down the furnace and the molten iron dripped out the bottom. From there it could be poured directly into molds and cast into the desired shape. This is obviously much faster and easier! But cast iron has much more carbon, which makes it very hard, lowers its melting point, and leaves it extremely brittle — you would never want a cast iron sword. (The behavior of various ferrous metals is determined by the way the non-metal atoms, especially carbon, interrupt the crystal structure of the iron. Wrought iron has less than .08% carbon by weight, modern “low carbon” steel between .05% and .3%, “high carbon” steel about 1.7%, and cast iron more than 3%.)

Yeah, I know they tell you not to do this because it will destroy the seasoning. They’re wrong. Don’t use oven cleaner; anything you’d use to wash your hands in a pinch isn’t going to hurt long-chain polymers chemically bonded to cast iron.

They’re oak dining chairs, probably (judging by the construction) about a hundred years old, and they looked a lot better on Facebook Marketplace than in real life. When I showed up to buy them, the sellers turned out to be an elderly couple moving to assisted living in six hours; they admired my baby and showed me pictures of their grandchildren and explained they had inherited the chairs from the wife’s mother, who in turn had gotten them from her friend’s mother, and by this point I couldn’t really say “yeah I can tell” and leave, so home they came. When I took apart the seats to recover them I discovered the original horsehair padding and some extremely questionable techniques applied over the years, but anyway now my chairs have eight-way hand-tied springs and I have some new calluses.

I'm reading all the old reviews and happened to read this the same day as the one for Burn, and it's interesting how both of them basically go back to the same point: That completely invisible facets of modernity are to some extent ruining people. With Burn, it was how the lack of physical activity is driving all manner of mental illness, depression, and neuroticism because the body's energy can't be expended on normal physical movement. Here, it's the systematic loss of agency created by hyperspecialization and mass production. Not sure I've ever seen anywhere else make the case that the steam engine directly leads to tfw no gf, but it's a thought that will stick with me.

I just wanted to poke my head in and say that it's a joy to read these reviews every week. When the emails show up, I tend to clear the deck and enjoy reading.

Thanks! I might even start expanding my reading genre in the near future. I'm learning about books in areas that I never knew existed.