REVIEW: The High Crusade, by Poul Anderson

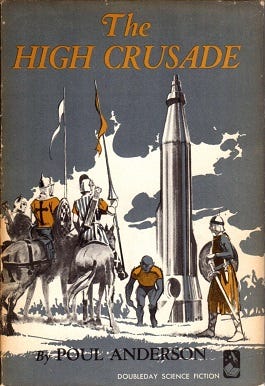

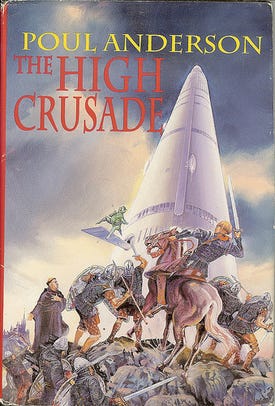

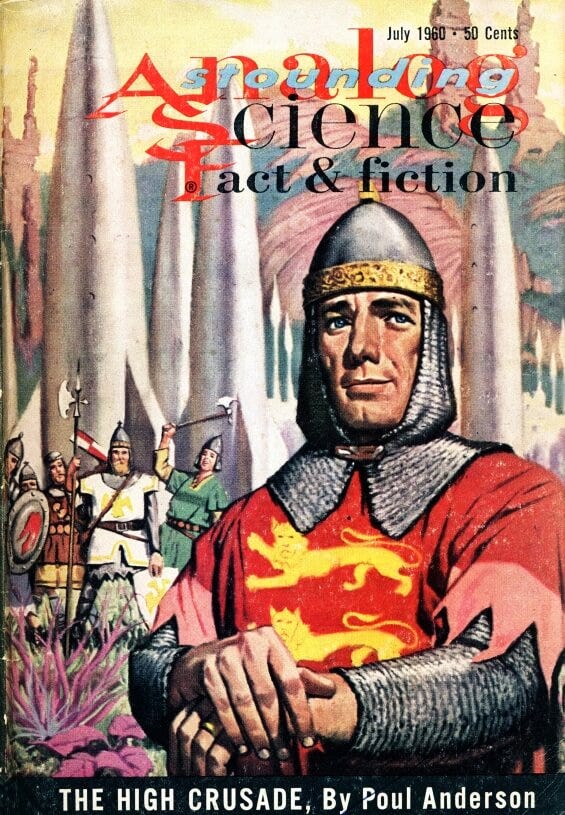

The High Crusade, Poul Anderson (1960; Baen Books, 2010).

The year is 1345. In the tiny Lincolnshire village of Ansby, Sir Roger de Tourneville is gathering men to join King Edward III on campaign in France. And then, suddenly, an enormous metal ship comes hurtling down through the sky at tremendous speed and lands in a pasture. Its blue-skinned occupants, rapidly disgorged and armed with rayguns, turn out to be a scouting expedition of the Wersegorix Empire, here to evaluate Earth’s suitability for colonization — after the subjugation or annihilation of its primitive inhabitants, of course. Unfortunately (for them), they’re utterly unprepared for English longbows or mounted knights charging up their gangway. Sir Roger prevails upon the sole survivor to pilot the ship, intending to use this fully armed and operational spacecraft to conquer the French and then liberate the Holy Land, and packs up the entire village in its capacious hold — who knows what they’ll need. Inevitably, of course, he is betrayed: the truculent Wersgor instead programs the autopilot on an unalterable course to his people’s nearest colony world. The English find themselves trapped on a distant planet, battling a vicious foe with dramatically superior technology, when it suddenly occurs to the young monastic narrator that under the two alien suns they have no way of determining the date of Easter. And that’s when they all freak out.

Speculative fiction — science fiction, fantasy, horror — shows us worlds that are somehow unreal in order to illuminate truths about what is real. We imagine colonists on Mars to tell stories about the human thirst for exploration, or a young wizard’s struggle with evil and power to explore what it means to grow up.1 Sometimes it casts light on a metaphorical truth by making it literal — in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, high school really is Hell and your boyfriend really does become someone else after you have sex with him; in The Half-Made World, the Western’s dichotomy between the lawless independent romance of the gunslinger and the ordering regularizing principle of civilization is made concrete as dueling sets of eldritch abominations. Sometimes it’s positing a single change and watching the effects ripple through society, and sometimes it’s the construction of an entire secondary world where any vast human (or elven) drama the author imagines can play out. But my favorite sort of speculative fiction — the one I’ll read no matter how bad it is, which is lucky because it’s usually pretty bad — is alternate history, which at its best uses the unreal to illuminate the lifeworlds of people very different from the WEIRD inhabitants of the 21st century.

Or, as a friend once put it (with an understandably dismissive tone, because I was explaining why I liked an objectively bad book), “It’s fun to play with LEGOs from different sets.”

But it is fun, and not just because you get to do things like the Battle of Cynoscephalae — only with the Mongols vs. the Aztecs. There’s something akin to simultaneous contrast going on: you notice the distinctive features of your little Roman legionary LEGO guy more when he’s on a little LEGO spaceship than when he’s in his little LEGO oppidum. Straight historical fiction (or worse, lazy fantasy cod-historical) makes it easy to get so caught up in the set dressing and events of the past that you don’t notice that your characters could be contemporary Americans.2 (I never want to read another novel starring a medieval bossbabe who prefers swordplay to needlework. That’s nice, honey, but what is your family supposed to wear?) Removing the characters from their familiar world, or presenting them with unfamiliar circumstances, forces the writer to really engage with what makes them different from us, and that’s something The High Crusade does magnificently. Its depiction of medieval Englishmen isn’t accurate, of course — this is a rollicking high octane thrill-ride, not a doctoral dissertation — but it doesn’t need to be accurate to get at something true.

It helps, of course, that the Wersgorix are a trifle…familiar. The initial parley between the two is deadpan hilarious, from the Wersegorix confusion at prayer (surely it must be some form of psionic augmentation, no creature capable of spaceflight would hold to primitive superstition) to their total incomprehension of the idea of high birth (some sort of selectively-bred warrior caste, perhaps?). They are highly advanced technologically, but determinedly rationalist in mindset. Brother Parvus narrates:

Actually the Wersgor domain was nothing at all like home. Most wealthy, important persons dwelt on their vast estates with a retinue of blueface hirelings. They communicated on the far-speaker and visited in swift aircraft or spaceships. Then there were the other classes I have mentioned elsewhere, such as warriors, merchants, and politicians. But no one was born to his place in life. under the law, all were equal, all free to strive as best they might for money or position. indeed, they had even abandoned the idea of families. Each Wersgor lacked a surname, being identified by a number instead in a central registry. Male and female seldom lived together more than a few years. Children were sent at an early age to schools, where they dwelt until mature, for their parents oftener thought them an encumbrance than a blessing.

Yet this realm, in theory a republic of freemen, was in practice a worse tyranny than mankind has known, even in Nero’s infamous day.

The Wersgorix had no special affection for their birthplace; they acknowledged no immediate ties of kinship or duty. As a result, each individual had no one to stand between him and the all-powerful central government. In England, when King John grew overweening, he clashed both with ancient law and with vested local interests; so the barons curbed him and thereby wrote another word or two of liberty for all Englishmen. The Wersgor were a lickspittle race, unable to protest any arbitrary decree of a superior. “Promotion according to merit” mean only “promotion according to one’s usefulness to the imperial ministers.”

Contrast this bland gray mediocrity with Sir Roger’s martial valor (the Wersgorix have forgotten hand-to-hand combat is even an option), personal initiative (the Wersgorix are supposed to wire headquarters for instructions), and, frankly, style, and it’s hard not to pump your fist every couple of pages. Science fiction always seems to turn humans into the Americans of space, even when they’re medieval Englishmen.

But they are still, recognizably, medieval Englishmen (of an admittedly caricatured sort, far more Plautine “types” than Shakespeare), and Anderson draws them with great affection. The things they love are shown to be lovable, the things they believe are shown to be good (if not necessarily true, since their faith is taken seriously but never quite authorially endorsed), and their “rich ceremonial and…government of individual nobles [one] could meet face to face” is shown to be better than the Wersgorix way of doing things. It is the Wersgorix we’re comparing them to, right?

You just don’t get books like this any more. And I don’t mean because the list of past civilizations for whom it’s socially acceptable to express unalloyed fondness without half a page of throat-clearing about their treatment of now-emancipated groups doesn’t include 14th century England. (That’s true but whining about it is boring.) You don’t get books like this any more because, of the two elements that combine to make The High Crusade such a delight — there’s fast-paced, slightly goofy, Technicolor adventure, but it’s wrapped around a core of real values and meaning — nerd culture has imprinted on exactly the wrong one.

My 50th anniversary Kindle edition opens with a number of appreciations from various famous nerds (several notable alt-history writers among them), but the first is from Diana Paxson, who along with Anderson was one of the founding members of the Society for Creative Anachronism. (It grew out of a costumed 1966 backyard jousting tournament and impromptu parade down Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue.) The SCA was, she writes, at least loosely inspired by what she calls The High Crusade’s “combination of authenticity, humor, and adaptability.” These days it describes itself as “selectively recreat[ing] the culture [of the Middle Ages], choosing elements of the culture that interest and attract us” (their emphasis), or perhaps as “the Middle Ages as they ought to have been” — namely, with indoor plumbing, gender equality, and noble titles as nothing more than names for the members who are taking their turns doing the organizational and administrative work. And don’t get me wrong, it seems like a perfectly cromulent hobby: I’m always interested in what we can learn about the past from attempts to recreate its material culture, and if you want to dress up and hit people with a boffer sword while you do it, you know, fine. If what draws you to history is archery or the minutiae of past weaving techniques or perfecting your open-flame cookery, or even just making pretty dresses, more power to you. But if what you long for in tales from the past is glory, honor, fealty — well, this is history with the heart ripped out. The forms are there, but the meaning that animated them is all gone.

It’s not really fair to pick on the SCA, which I mention only because my Kindle book did and I found the contrast so striking. This phenomenon is everywhere in contemporary nerd culture, including speculative fiction, and especially in fantasy. Nerds are still capable of telling stories about friendship or self-actualization or rebellion against oppression, but fantasy in particular is so deeply occupied with kings and wars and high politics that the inability to come to terms with why those things matter leaves the genre empty. If most modern fantasy is (as Terry Pratchett once said) rearranging the furniture in Tolkien’s attic, it does so without ever actually taking the things down out of the attic and putting them to their proper uses. Tolkien had a vaguely medieval setting, but it was suffused by deeply medieval values (and often expressed in fabulously medieval forms). His inheritors merely deploy the set-dressing, and generally not as well. Even the Lord of the Rings films can’t really pull it off: Viggo Mortensen’s Aragorn is compelling as a dirty ranger of the North, but as a king of the line of Elendil he looks vaguely constipated. Few indeed are the new books that pay more than lip service to concepts like duty, honor, authority, or hierarchy, and those that really consider them are almost always trendily cynical grimdark fantasy, trotting out these old familiar friends just to bloodily subvert them before your horrified eyes. Frankly I’ll take that over a moral core of damp cardboard (at least it’s an ethos), but it’s not a lot better.

Not that every hero needs to be Aragorn, of course — a moral universe not yet shorn of all its richness has plenty of room for Conan and Elric and Cugel, for Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, and, yes, for Sir Roger de Tourneville. But those were books written by human beings, not bugmen, and if you loved them then most speculative fiction is going to disappoint you. That’s not your friend any more; that’s the thing that killed your friend and is wearing his skin as a suit.

All of which makes The High Crusade even more of a delight now than it must have been at its 1960 debut. It’s a hard book to assign to a genre: I’ve talked here about alt-history, which it resembles in its mixture of the historical and the speculative, and fantasy, with which it shares a vibe even though there’s no magic. (Of course there’s an alien spaceship so it’s definitionally sci-fi.) But it doesn’t really matter what you call it, because it remains both tremendous fun and a reminder of what we love about the little LEGO knight.

You guys, I’m obviously talking about A Wizard of Earthsea. Read another book.

Or maybe it’s intentional, stemming from a writer’s worry that portraying a truly foreign worldview would alienate their readers. Even Dan Davis, who’s doing an otherwise very fun (and prehistorically accurate) early Bronze Age fantasy retelling of the Hercules myth, regularly has his Yamnaya (“Heryos”) hero reflect on and then deliberately buck cultural expectations about the treatment of social inferiors like women, slaves, and Early European Farmers. The Watsonian explanation is pity, but frankly it makes the demigod come off as a bit of a wimp.

"Nerds are still capable of telling stories about friendship or self-actualization or rebellion against oppression, but fantasy in particular is so deeply occupied with kings and wars and high politics that the inability to come to terms with why those things matter leaves the genre empty."

My favorite telling of how jarring it is to displace a king, even a bad king, is Shakespeare's Richard II. I've only seen the Hollow Crown production, so that's what I'm going with, but they made the scene where Richard is dispossessed of his crown excruciating. And the production in no way believes he's a good king or even a tolerable one! But you get such a clear sense that the king that follows cannot be king in the same way, and that removing a bad king badly breaks something.

The other good example of how different a king might be than "the one who is currently in charge" comes in Macbeth, when Edward the Confessor never appears on stage, but he is curing scrofula nearby off stage when Malcolm is in England, and it's Malcolm's reverence for/awe of Edward that establishes he might be able to restore his nation, not just remove Macbeth.

What a delightful review. Thanks for reminding me of how great this book is. I haven’t read it for years but now I need to dig it out of storage and give it to my sons to read. Thanks.