GUEST REVIEW: Alexander to Actium, by Peter Green

Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, Peter Green (University of California Press, 1993).

In the 4th century BC, the Greeks conquered the world. And that is where their problems began.

When I was a child first getting interested in ancient history, the books I read followed a smooth narrative process. The story of the Greeks began with Athenian democracy and the victories at Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea that saved Western civilization from Persian conquest. Then there was the Athenian maritime empire, and its tremendous cultural achievements: the Parthenon, Socratic philosophy, the plays of Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes. There was the Peloponnesian War and Thucydides’s chronicling of it. And then, in a tremendous climax, there were the awesome conquests of Alexander the Great, who destroyed the most powerful empire on Earth and conquered the known world by the age of 33, only to die young and have his empire swiftly broken up after his death.

…And then the story would promptly lurch 700 miles to the northwest and start over. Greeks? What Greeks? Now I was reading about the rise of a different city, Rome, and the achievements of its great republic. Instead of the Assembly and the ostracism, there was the Senate and the consuls. I would read about the Samnite Wars, the Punic Wars, the Gallic Wars, and finally the great civil wars that transformed Rome from a republic into the empire that men still think about a few times a week. In this story, the Greeks appear again, but only as enemies for Rome first to easily defeat, then be culturally influenced by. This fusion of Greek and Roman culture leads to European Christianity, the Renaissance, the cultural canon — in a word, the West itself.

Kid me didn’t think too much about it at the time. But as I grew, I and many others finally had a thought intrude: Wait a minute, what the heck was going on in Alexander’s old empire before the Romans got there?

And if you’re like me, asking that question is how you wind up reading Alexander to Actium.

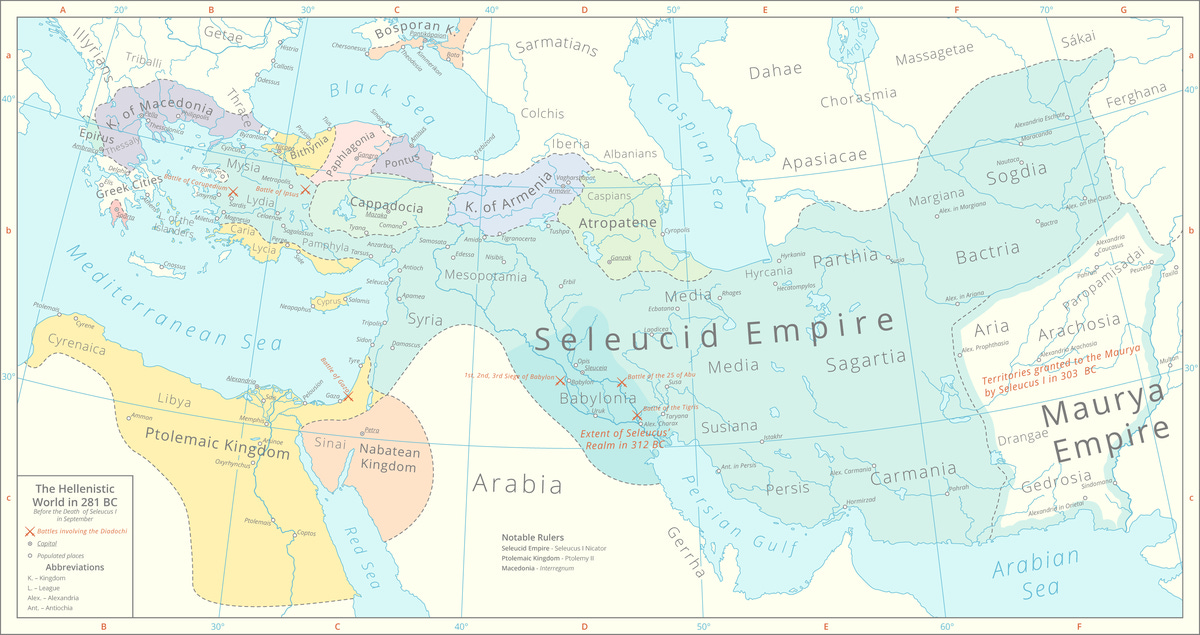

Alexander to Actium is classicist Peter Green’s gargantuan tome covering the period historians now call the Hellenistic era, the 293-year span following the death of Alexander the Great during which his vast but short-lived empire was divided up and ruled by ethnically Macedonian and Greek elites who left the stamp of Hellenic culture all across the eastern Mediterranean. The era begins with Alexander’s generals (the Diadochi, “Successors”) waging an epic forty years of war as funeral games for their dead master before finally settling into a more stable system with three great kingdoms centered on Macedon, Egypt, and Syria (plus lesser monarchies like Pergamon and Bactria). These kingdoms battled one another and Rome for another quarter-millennium, gradually losing land and power before they were extinguished, one by one. The last Hellenistic kingdom, Ptolemaic Egypt, made it until 30 B.C., when the legendary Cleopatra1 committed suicide and her realm became the personal possession of Octavian, the future Caesar Augustus. Long after their destruction, the Hellenistic legacy lingers most in religion: the Christian New Testament was written not in the Hebrew or Aramaic of Judea or the Latin of the Roman Empire, but in the koine Greek that had become the lingua franca of the educated eastern Mediterranean.

The ebb and flow of this 300-year historical epic is one that really deserves a trashy big-budget TV adaptation or three. The sordid acts of the Successors and their successors are so spectacular they could easily be made into a hybrid of HBO’s Rome and a popular show about dragons that shall remain nameless. I’m a little shocked one hasn’t been made already. To give just a small set of anecdotes from Green’s work:

After an attempted army revolt following Alexander’s death, the general Perdiccas holds a “purification” ceremony for the army, which consists of rebel leaders being publicly trampled to death by elephants.

Antigonus One-Eye, the man who came closest to reuniting Alexander’s empire, was very tall, very wide, very old, and had a very good nickname. Huge in size and huge in ambition, he dies fighting in battle at over 80 years old at Ipsus, a battle featuring 25,000 cavalry, 120 scythed chariots, and almost 600 elephants.

Olympias, Alexander the Great’s mother, is so vindictive that when Philip II dies, she has a rival wife and her infant daughter roasted to death on a charcoal brazier even though they pose zero dynastic threat. When her own end comes during Macedon’s multiple civil wars, the soldiers of Cassander refuse to kill Alexander’s mother – so she is instead stoned to death by the families of those she had killed during past purges.

Seleucus I, founder of the Syria-based Seleucid Empire, is happily married to his second wife Stratonice when he notices his son, Antiochus, is deeply enamored with her. No worry: Seleucus simply divorces Stratonice and has her marry Antiochus. This is actually a happy ending and works out for everyone, surprisingly.

Lysimachus, king of Thrace, is happily married to his third wife, Arsinoe, when she tricks him into having his son by a first marriage executed so her own son can succeed. This sparks a war that kills Lysimachus and destroys his kingdom, somewhat botching the whole succession thing. But no worries: Arsinoe escapes to Egypt and makes out just fine by marrying its pharaoh – her brother.

Cassander, king of Macedon, gets so irate at clever jabs from the wily Athenian politician Demades that he finally snaps and personally chops both Demades and his son to pieces while screaming insults at them.

For about a decade during the various successor wars, Athens is ruled by a literal philosopher-king, the thirty-something Macedonian puppet Demetrius of Phaleron. One of his agenda items is building a gigantic mechanical snail to crawl through the streets of Athens leaving a realistic trail of slime behind; this is apparently some artful way of shaming the Athenians for being sluggish in standing up for Greek freedom.

After Demetrius the Philosopher King is overthrown (by a different Demetrius, long story) the new tyrant takes advantage of divine honors granted to him to house his hoes in apartments at the back of the Parthenon. He tries to seduce a teenaged boy who instead commits suicide by jumping into a tub of boiling-hot water, and another time waives a fine against a prominent Athenian citizen in return for taking his son as a catamite. When you are legally a god, they let you do it.

Aratus is a quite successful Greek general with the unfortunate problem of getting uncontrollable diarrhea before every battle.

Escaped slave and rebel Drimakos defies authorities on Chios so successfully they simply reach a treaty with him: As long as he doesn’t steal too much and only accepts new slaves into his army who were severely abused by their masters (while sending the rest back), they’ll leave him alone. Drimakos lives to a ripe old age, then has his boy lover kill him and take his head in to claim a reward. Later, Drimakos’s spirit would supposedly appear to Chians in their dreams to warn of plots by their slaves.

To show off their power, the Ptolemies commission a grand procession through Alexandria whose centerpiece is “a gaudily painted gold phallus, almost two hundred feet long … and tied up, like some exotic Christmas present, with gold ribbons and bows.” Green reasonably wonders how this mighty phallus was able to negotiate corners.

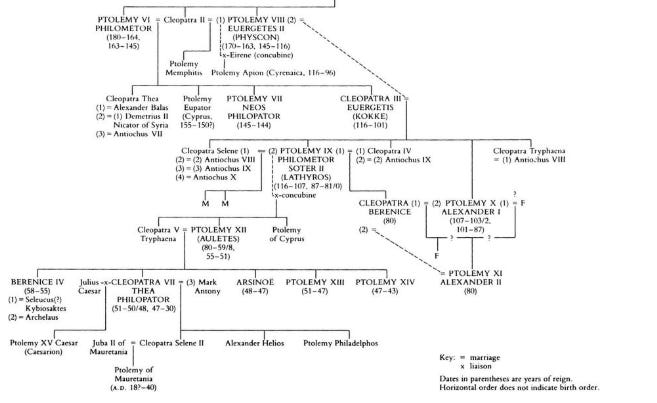

The later Ptolemies could win some kind of ghastly award for their spectacular decadence. Ptolemy VIII Physcon (“the Obese”), who resembles a 2nd century BC Baron Harkonnen, seizes power after the death of his brother (also named Ptolemy) by marrying Cleopatra, who is also their sister. He then has her son, his nephew (also named Ptolemy), murdered during the wedding feast, then proceeds to seduce and marry his pubescent niece (also named Cleopatra). A decade later, riots forced Physcon and his niece-wife into exile, and his sister-wife proclaims her son by Physcon (another Ptolemy) as pharaoh, but the heir is apparently in Cyrene at the time, allowing Physcon to capture his unsuspecting son and send his dismembered corpse to the sister-wife as a birthday present. Meanwhile, the sister-wife’s daughter by her first brother (named Cleopatra, of course) gets married off to a Seleucid king and uses her sons as a series of puppets. The first puppet, Seleucus V, proves troublesome, so his mother murders him by using him for archery practice. The second puppet, Antiochus VIII, is more canny, and when his mother tries to murder him with a cup of poisoned wine, he notices something is up and forces her to drink the fatal cup herself. Antiochus VIII then fights a long civil war against his half-brother and cousin Antiochus IX, who is not a puppet but instead has the private hobby of playing with literal giant puppets. Got all that?

If learning the above is your idea of fun, then Alexander to Actium is a rich feast, enlivened throughout with Green’s flare for delicious details and legends that are possibly fanciful but too remarkable to leave out.

But telling the actual narrative of the Hellenistic world, however bizarre and entertaining it gets, is really only the superficial purpose of Alexander to Actium. No, the real point of the book, and the real reason to stick around for all 700 pages, is to witness Peter Green’s incredible, almost maniacal act of vengeance against an era he despises.

Whether it’s playwrights…

The poet-playwright Menander … has always struck me as a classic example of a growth industry created by papyrological accident.

…poets…

Callimachus, like Ben Jonson, has always had a rather better press than he deserves, and for much the same reason: his academic ideals and credentials can hardly fail to appeal to those other academics … I cannot help finding him at once pretentious and faintly distasteful, a literary exhibitionist with an unpleasant groveling streak about him, a sycophant implacable in his attacks on rival sycophants[.]

…philosophy…

Popular philosophies — and Stoicism must be accounted one of the most popular ever — almost always tend to have an intellectually suspect quality about them.

…coin portraits…

Prusias I of Bithynia is porcine, crass, and self-satisfied. The early kings of Pontus resemble nothing so much as a family of escaped convicts: Pharnaces I has the profile of a Neanderthaler, and Mithridates IV that of a skid-row alcoholic.

…or academia itself…

Museum faculty developed a reputation for symposia, frivolous research topics, and alcoholism: to anyone in the same profession there cannot fail to be a certain sense of deja vu.

…Green knows how to write a burn. It’s not simply that he’s a hater: his book about the Battle of Salamis overflows with love and admiration for the golden age Greeks who defeated the Persians. No, Green specifically has a bone to pick with the Hellenistic era and its rulers, its people, its art, and its ideas. For those who read for entertainment, the best part of Alexander to Actium isn’t the battles, the George R.R. Martin-esque politics, or the even more Martin-esque incest — it’s tagging along as Peter Green gets revenge on the Hellenistic Age by writing a definitive textbook about it, so that all students of history who come after him will read of his scorn and contempt.

Green’s harsh attitude is clear right from the preface, when he sets the book’s scope.

[I will not] devote specific sections either to law or to school education, on the grounds that during our period the first … was little more than an elaborate sham masking the realities of power, while the second offered nothing, in essence, but literary rote learning, elementary mathematics, music, athletics, and—most important—a rhetorical grab bag that would enable men at the top to talk their way into, or out of, anything.

Hellenistic historiography fares just as badly:

Polybius remains the only worthwhile historian of the Hellenistic period whose work substantially survives. Diodorus, as we are too often reminded, is a third-rate compiler … I have no wish to burden an already overlong book with yet another imaginative analysis of his chronological inconsistencies and synthetic rhetoric. Like Plutarch, he believed that one virtue of history lay in “recording the nobility of distinguished men, publicizing the vileness of the wicked, and in general promoting the good of mankind.” Successful statesmen, he thought, were righteous, while evil ones met with frustration: nothing, in short, succeeds like success. None of this inspires confidence.

From there the savagery continues almost non-stop, right down to the last page when Green ridicules imperial Roman literature for “guttering out” by the mid-2nd century. Virtually nothing escapes.2

Take philosophy, that most noble of ancient endeavors. The Hellenistic world’s biggest philosophical contribution was Stoicism. Today, Stoicism enjoys a good reputation for encouraging adherents to be stolid and uncomplaining in the face of difficulties. Green, though, puts the spotlight on Stoicism’s lesser-known traits like its determinism and pantheism, then singles it out as a shallow ideology perfect for helping elites rationalize their own hypocrisies.

Sandbach correctly notes that “the belief that the world was entirely ruled by Providence would have an appeal to the ruling class of a ruling people.” What Stoicism offered, in fact, was a built-in justification—moral, theological, semantic—for the social and political fixed order: it was the most powerful and subtle instrument of self-perpetuation that the Hellenistic ruling class ever conceived. The mere fact of anything happening meant that it had been fated to happen; and since nature was providentially disposed toward mankind, what was fated could not fail to be all for the best. This interesting version of determinism is most often presented as a source of comfort when things seemingly went wrong; but of course, as I have suggested, it would be of even greater benefit to those who were anxious to have some moral principles to offer the world in justification of ruthless self-interest. If it was bound to happen, it had to be right.

People have always wanted to learn the future, but Stoicism’s belief in a deterministic yet providential cosmos drove a tremendous increase in the popularity of astrology, divination, and other woowoo, often egged on by the philosophers themselves.3 Green even hypothesizes that Stoicism’s popularity directly sabotaged whatever nascent scientific progress there was in the late Hellenistic age.

But if Stoicism was the shallow George W. Bush evangelicalism of its day, it at least fares better than Epicureanism, the other popular and enduring school of Hellenistic thought. The traditional Christian attack on Epicurus was that he was an atheist and hedonist. More modern scholars emphasize that Epicurus’s belief in pleasure as the highest good actually encourages moderation and avoiding pain or fear so as to achieve tranquility.

Green picks neither of these interpretations, instead arguing that Epicureanism was totally a cult. Epicureans joined communes after swearing oaths to obey “the Leader,” whom they “flattered like a god.” “Act always,” they were told, “as though Epicurus is watching.” The Leader “seems to have enjoyed droit de seigneur with several of his followers’ wives and mistresses.” In Epicurus’s famous Garden outside Athens, nobody actually worked, with the commune instead sustained in “endowed leisure” by donations extracted from supporters across the Mediterranean. “Send us, for the care of our holy body, first fruits on behalf of yourself and your children,” Epicurus writes to one of his disciples. In Green’s telling, “Epicureanism was, in the last resort, the brainchild of an antisocial and anti-intellectual dogmatist, with a bee in his bonnet about providential gods, and more than a passing urge…to replace the deity himself.”

Quite the cynical attitude…except that Green is just as harsh on the literal Cynics. Being an ascetic who lives on the street in ostentatious poverty while engaging in public defecation and masturbation doesn’t make you a rebel, it just makes you a loser:

The lifestyle is strictly self-promoting; it has no real ulterior end in view. We adopt the lifestyle to be happy. Happiness is defined through the lifestyle, which becomes an end in itself. The manipulation of these social concepts, the “natural” and the “shameless,” simply gives the Cynic an excuse to thumb his nose at the society he is busy rejecting. … Worst of all, the so-called self-sufficiency is a patent sham. The Cynic, in the last resort, exists as a tolerated parasite on the society that he condemns. … The situation is not unfamiliar today.

Hellenistic art fares a bit better than philosophy, but only a bit.

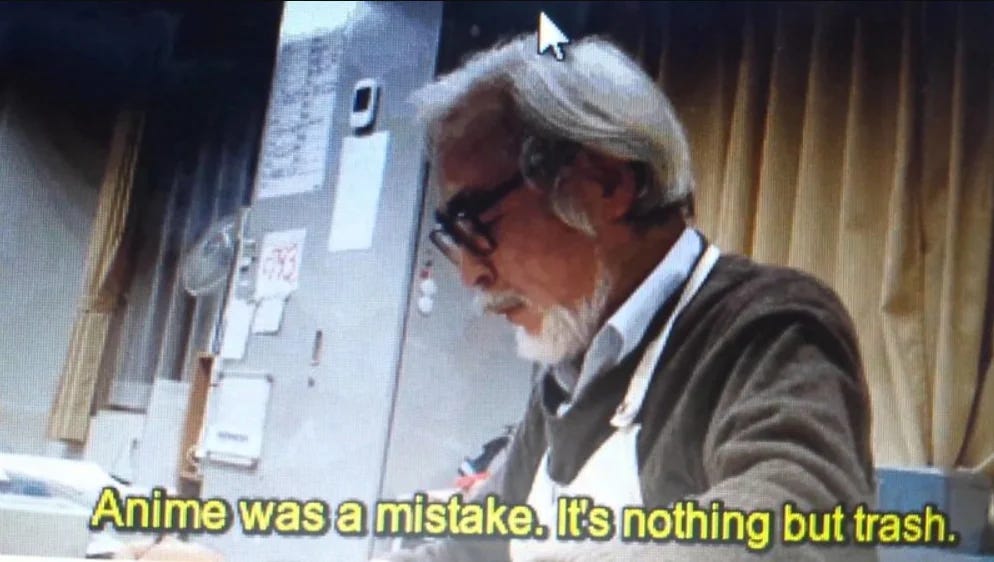

If you’re at all online (condolences if so), you may have seen this meme once in your life.

The man in the image is Hiyao Miyazaki, director of some of the most famous anime films of all time (Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and more). The quote is fake, but inspired by real comments a jaded Miyazaki once made in an interview:

Some people spend their lives interested only in themselves. Almost all Japanese animation is produced with hardly any basis taken from observing real people, you know. It’s produced by humans who can’t stand looking at other humans. And that’s why the industry is full of otaku!

In short, anime has been ruined because it is now made by people whose sole life experience is being die-hard anime fans. And so, far too often, anime has simply become a mixture of fanservice, self-referential masturbatory impenetrability, and crass wish fulfillment. It has minimal artistic merit because the creators are pure consumers, with nothing real or interesting to say.

Fortunately, Green is here to tell you that this exact same wretched pattern was already around in Alexandria, Athens, and Antioch during the 3rd century BC. The greatest poetic innovation of the Hellenistic Age is pastoral poetry. And what is pastoral poetry? That’s right, low-effort wish fulfillment:

Pastoral poetry … is invariably produced by urban intellectuals who have never themselves handled a spade, much less herded sheep, goats, or cattle, in their lives. … It grafts a kind of yearning idealism onto a reality that was, in fact, peculiarly harsh and unrewarding. … That this should be an exclusively urban phenomenon is no accident. The real shepherd or farmer knows, too well, that his life is poor, dangerous, backbreaking, and without respite.The pastoral dream, then, is the special property of the gentleman poet, living on patronage from a Ptolemy or an Augustus: when Marie-Antoinette played at being a milkmaid, the charade did not require her to get up at four in the morning and milk obdurate cows in freezing weather with chilblained hands.

The pastoral genre peaks in silliness with the ancient romance Daphnis and Chloe, where two young shepherds are too innocent to know about sex — an absurdity once you remember they live around livestock. Yet as silly as it is, the pastoral endlessly recurs in history, always there to satisfy the craving for cheap nostalgia or easy escapism. It could be the most enduring art form pioneered by the Hellenistic age.

…Or it would be, if not for the slop they were churning out in the theater. There, the Hellenistic growth industry is the New Comedy. Just as with pastoralism, the defining feature of New Comedy is escapism. The satire of Aristophanes (so biting it got Socrates killed) gives way to stock characters and flimsy plots totally detached from real-world concerns. New Comedy is a landscape of “comfortable cliché and romantic fantasy.” Every story has a happy ending. Twenty-three hundred years before television, the Hellenistic Greeks invented the stale network sitcom. In one of the funniest digressions I’ve ever read in a serious history book, Green dedicates half a chapter to a detailed, scene-by-scene thrashing of the most popular Hellenistic playwright, Menander (he of the “papyrological accident”):

[Menander’s corpus] abounds in situational idiocies. Take the Arbitrators (Epitrepontes) … a young stud, Charisios (“Charmer”), having raped one Pamphile (“Darling”) during the inevitable night festival, gets married, only to discover, first, that the girl he married has a baby five months later, and then, as a dénouement, that she was also the girl he raped, and that the child is therefore presumptively his. … Disbelief, though suspended, keeps breaking in. Why, we may legitimately ask, did Charisios not have the problem of her five-months’ child out face-to-face with his wife instead of listening to the servants? Why, instead, does he simply walk out on her in a huff and take up with Habrotonon, a guitar-strumming floozy with the usual heart of gold? No play otherwise, the cynic might answer; rational plots are not exactly Menander’s forte.

… [W]e are being asked to accept as fact that the soap-opera plots, the popular aphorisms, the commonplace moral values, stock characters, stereo-typed opinions, and cliché-ridden dialogue were all concessions made by this intellectual and creative paragon to the Aunt Ednas of the Athenian bourgeoisie, whereas any flashes of brilliance that can be detected in his work are ascribed to the genius he was forced to restrain while pursuing the bitch-goddess success. In that case, quite apart from the innate immorality of such a proceeding (once a whore, always a whore, as Orwell remarked in a very similar modern context), one can only point out that Menander’s essay in self-prostitution did him singularly little good. Eight victories in over a hundred attempts is hardly the record of a clever crowd-pleaser.

Not all art was mass-market schlock. Some of it fell on the other end of the scale: Works so dense and learned they were nearly unreadable. To cite merely one line from Lycophron of Chalcis’s poem Alexandra:

“The centipede lovely-faced stork-colored daughters of the Bald Lady struck maiden-slaying Thetis with their blades” (22–24) simply means that Paris’s hundred-oared ships, built of timber from Bald Mountain (Phalakra) in the Troad, painted with the apotropaic eye on their bows, hulls pitch-black, like storks (more plausible than white, the other prevalent color of European storks), dipped their oars in the sea, more particularly the Hellespont (since this claimed the life of the maiden Helle), Thetis qua sea nymph being used by synecdoche to represent the sea itself. Every line requires this kind of exegesis.

Who wanted this? In truth, almost nobody, but that was the point. “[B]eginning in the fourth century, literature moved away from the public arena, to become the property of a private, very often subsidized, intellectual minority.”

Normally all this negativity would get grating, but Alexander to Actium would be a lesser book if Green admired his subject more. The fact he doesn’t, and why he doesn’t, is what elevates this book from merely informative to exceptional.

Because, besides being fun, all of Green’s jabs and bitter humor serve a purpose. They answer a central question about the book itself and the era it describes. Superficially, the Hellenistic era seems like the Ancient Greeks at their apex. They were culturally and politically dominant over half the Mediterranean. They had spectacular wealth, plundered from Persian treasuries or extracted from Egyptian fellaheen. Their cities were larger and their patronage more lavish than any prior era. So why does the average well-educated Westerner know almost nothing about them, while knowing a lot about the comparatively tiny city-state of Athens?

Simple: because beneath the mighty empires, so impressive on a map and so rich when seen as museum exhibits, the world of a Hellenistic Greek was miserable. His governments were tyrannical, exploitative, decadent, and distant. His economy was one of ever-fewer masters and ever-more slaves. His religion no longer satisfied and was abandoned en masse by the elites who once safeguarded it. And then, looming over the horizon, there was the ever-rising Roman superpower, culturally backward yet militarily unstoppable, chipping away at Greek power so steadily that the Greeks accepted they were doomed decades before actually being conquered.

This was more than just tough times. It was a great civilization going into eclipse. It was an age defined by “…loss of self-confidence and idealism, displacement of public values, the erosion of religious beliefs, self-absorption ousting involvement, hedonism masking impotent resentment, the violence of despair, the ugliness of reality formalized as realism, the empty urban soul starving on pastoral whimsy, sex, and Machtpolitik.”

Why were the Greeks in a psychological funk? The word that comes to mind again and again is autonomy.

Golden age Greece was a Greece of countless poleis, individual city-states constantly in competition with one another: Athens, Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, Argos, and so on. Citizens were part-time magistrates, jurors, lawmakers, and soldiers. A man seeking status almost always sought it by becoming a great man in his own city, but even if he was a person of no consequence he had a direct stake in his city’s success and a role to play in achieving it. A man’s gods were the gods of his city, worshipped since time immemorial, with few people asking awkward questions about where they came from or whether they were, strictly speaking, actually real. In the Greece of city-states, the squabbles were petty, but never meaningless. In a land without kings, every man was a player character.

It was this quarrelsome, decentralized patchwork that produced the Greek miracle: the birth, in a remarkably short period, of the Western world’s foundational works of philosophy, history, science, and drama.

With Alexander’s godlike achievements, though, that old Greek world crumbled. Suddenly, Greek civilization was dominated by massive kingdoms, ruled by kings whose only claim to legitimacy was that they or their fathers had won their lands at the tip of a spear. These kings quickly took a liking to the trappings of Oriental rulership, styling themselves first as “saviors” and then simply as “gods,” spectacularly above and apart from the people they ruled. Their kingdoms were essentially for-profit estates run for the benefit of the mighty god-kings. Alexandria, the crown jewel of the Hellenistic world, home to the Great Lighthouse and Great Library, was effectively a giant consumer good for the Ptolemaic royal family, where all the surplus of Egypt’s countryside had to be shipped, on pain of death. In a city of perhaps half a million, royal palaces occupied as much as one-third of the land.

In the decades of war that followed Alexander’s death, the Greek cities soon learned that their future was to be in a constant state of servility to one overlord or another. The “freedom of the Greeks” changed from a point of pride to a pathetic sham:

The cities went through the motions of freedom, but in the last resort they did so on sufferance. What they really felt about their de facto subjection can be inferred from the carefully euphemistic terminology employed … [Officials] had “spent time with” the king, or had “gone abroad” with him, or had “enjoyed his friendship”: anything to circumvent the notion of paid service, and perhaps a residual unwillingness to face the grim fact of political impotence. It is significant that later this objection fades: by 200 the honorand’s court title is being expressed openly, without circumlocution.

This is where my boyish enthusiasm to learn more about the great Hellenistic empires led me astray, because while vast empires look so impressive on a map and are so fun to play in a 21st-century video game, they gradually destroyed what had made the Greeks such a dynamic civilization. Instead of reflecting civic pride, great temples and festivals simply displayed the profligacy of rulers. Patronage emanating from a tiny handful of elites led to sycophancy and parasitism. The desire of ruling dynasts to preserve power at all costs, coupled with ignorance of economics, led to a suffocating stagnation like that seen in many an Oriental despotism.

Fittingly, one of the only Hellenistic entities Green has clear enthusiasm for is the small trading republic of Rhodes. Everything that the great eastern kingdoms were, Rhodes was not. Thanks to its victory against Demetrius the Besieger (the same guy with the Parthenon harem) in 304 BC, the city kept its independence and was “the last bastion of genuine freedom” in the Aegean Sea, a reservoir of “the old classical Greek pride and civic intransigence.” When famine struck, Rhodian policy was to supply emergency grain at cheap prices rather than to price gouge, and a similar welfare program provided for the city’s own indigent. To keep the seas free for trade, Rhodian ships waged war against pirates to the benefit of all. While other states used mercenaries to do their fighting, Rhodian galleys were crewed entirely by Rhodian citizens, like the Athenian triremes at Salamis centuries before (and unlike Athenians triremes in Hellenistic times). So popular was Rhodes that when the city was leveled by an earthquake in 228 (knocking down its famed Colossus), the great powers of the Mediterranean competed with each other at donating funds for its reconstruction.

But few Greeks had the privilege of being Rhodians. And when they lost their independence and autonomy, it was as though everything else was lost with them. For the Greek colonists of the new great Eastern metropoli, the Olympian twelve were no longer enough, and earnest belief in them among the urban and educated precipitously declined. Notably, in the 4th and 5th centuries BC governments would petition the Oracle at Delphi for prophecies, but by Hellenistic times only individuals still bothered.

In the place of the old gods came new ones: syncretic deities like Serapis (a composite of Zeus, Osiris, and the Apis bull), radically altered ones like Isis, and flourishing mystery cults that promised adherents that, however unpleasant this world was, secret rituals could lead to a better one in the afterlife. But the most distinctive new religious trend was the cults honoring the new dynastic rulers themselves, acclaimed not merely as kings but as gods on earth. When Demetrius the Besieger arrived in Athens in 291 B.C., he was greeted with a paean that went:

The other gods are far away,

Or cannot hear,

Or are nonexistent, or care nothing for us;

But you are here, and visible to us,

Not carved in wood or stone, but real,

So to you we pray.

Was this belief literally real? Almost certainly not. But when nascent atheism is becoming a more and more common assumption, it is easy for sycophancy towards the powerful to take the place of religion.

At some point while reading Alexander to Actium, a thought will break in. Maybe it’s when Green lists the chief virtues of Hellenistic philosophy, all of them negative: “aponia, absence of pain; alypia, avoidance of grief; akataplēxia, absence of upset; ataraxia, undisturbedness; apragmosynē, detachment from mundane matters; apathia, non-suffering.” Maybe it’s when he narrates the doomed effort of Cleomenes III to Make Sparta Great Again. Whatever it is, eventually one realizes Green isn’t just describing long-dead Greeks. He is also describing us, another civilization in an existential funk, going through an abrupt decline from a dizzying peak.

We too live in the wake of a great conquest like Alexander’s. In fact, we live in the wake of two: first, the great-but-vanished European empires of the 19th century, and second, the Pax Americana, the economic and cultural domination of most of the world by America, its values, its way of looking at the world.

Like a Greek in Alexandria or Antioch, we live amid great superficial abundance. Set aside whatever angst you have about housing prices and you know it’s true: your access to food, entertainment, and creature comforts would be a marvel not just to the distant past but even a person from the 1980s.

What has gone missing? The same things that were vanishing for those Greeks 2300 years ago. The faith the West held when it swept the world before it has been abandoned en masse, yet even as irreligion has surged enthusiasm for superstitious woowoo has remained untouched (or even grown). Art is plentiful, yet stagnant, and many people are apparently content with lowest-common-denominator AI slop.4 And then, looming in the background, there is the unease that whatever material prosperity we have is borrowed from the future, passing the time until foreign peoples and nations surpass us…or simply replace us.

The more of Green one reads, the more unsettling the parallels. As Greece headed for its final disintegration and conquest in the 2nd century B.C., birthrates collapsed. Polybius claims the well-off preferred to live lives of pleasure without marrying, or to have one or two children at most, “so that they could leave them in affluence and bring them up to be spendthrifts.”5 Foodie culture thrived: “Infatuation with haute cuisine became, at least among the propertied classes, a kind of substitute religion.”

Perhaps the single most important thread tethering Green’s world to our own, though, is the loss of sociopolitical agency. Like 5th-century BC Greece, 19th-century America was a paradise of self-government. Americans settled the frontier, founded towns and colleges, set up governments, formed associations, launched business enterprises, expanded and invented and built, all with shockingly little central government control.

On the other hand, today’s America is a lot more like 2nd century BC Greece. What changed? America didn’t get conquered or become a monarchy. We are still an “Our Democracy,” as the BlueSky pundits never tire of saying. But, much like with the fraudulently autonomous poleis of Hellenistic Greece, the ghost has (mostly) gone out of American self-government. A combination of atomization, urbanization, and political nationalization mean the average American’s control over their own government is lower than ever. Americans see bad laws, bad ideas, bad policies, and bad social trends all over the place, but when any change of course requires taking control of a country of 340 million, what hope is there? A large country where everything that matters is centralized will inevitably create an apathetic populace. Most people will simply check out and give up, or look for an easier way out. The Hellenistic Greeks put their faith in god-kings; today, millions of Americans put theirs in God-Emperors.

There are no happy endings in the fall of a great civilization. Like Hemingway’s bankruptcy, the Greek implosion happens gradually and then suddenly. In Greece proper the Achaean League of southern cities repeatedly allies with Rome to help it destroy Macedon, only to abruptly realize in 146 BC that it is next:

When Critolaus marched north to discipline the apostate city of Heracleia he found himself, to his horror, confronted by a Roman army under the redoubtable Metellus. At Scarphaea, near Thermopylae, he was crushingly defeated, and may have committed suicide. …A kind of passionate last-ditch determination swept the country. Boeotia and Euboea, Phocis and Ozolian Locris joined the League’s forces. The mood resembled that of the American Old South in 1860, and the military preparations were no less inadequate. Nor, clearly, had a vigorous Roman offensive been foreseen. Through the fiery rhetoric we glimpse disorder, civilian panic, flight. Yet once committed, the cities of the League reveal an unshakeable determination to fight on, whatever the cost. A few prominent citizens, predictably, argued for capitulation: they were imprisoned or executed. …Polybius paints a scene of panic and confusion sweeping the cities of Greece. …Despite the fact that he had executed at least two subordinates who urged surrender on terms, Diaeus, instead of holding out, fled by night [for] Megalopolis, where—like the Gaul commemorated by Attalus I’s Pergamene sculptors —he first slew his wife to prevent her falling into Roman hands, then committed suicide. The Achaean War was over, almost before it had begun. Mummius gave his troops carte blanche to loot and destroy Corinth. … Women and children were sold into slavery; any men still in the city when it fell were slaughtered without mercy..

A few years later, the kingdom of Pergamon doesn’t even bother to fight a doomed war. Instead, its final king simply wills his kingdom to Rome rather than let it inevitably be violently devoured.6 The Seleucid kingdom is rendered so pathetic by repeated civil wars that its final destruction is a borderline afterthought, a mere item of business as Pompey the Great reorders the East. When the last Hellenistic state in Egypt finally falls, it is a conquest long overdue — and while Christian apologists know to point out that the Great Library was probably destroyed by Caesar rather than angry Christians, the truth is even that is probably untrue. By 30 B.C., Alexandria’s best artists and scholars were long-gone and the library was a relic.

But amid the despair of civilizational destruction, Alexander to Actium offers a peculiar sort of hope.

Even as the Greeks collapsed, their cultural legacy would live on thanks to the fortunate biases of their conquerors. As Rome thrashed the Greeks in one war after another, it only grew more and more philhellenic in its attitudes, no matter how much the Greeks themselves saw the Romans as uncultured boors. Most of our surviving Greek art actually comes from the huge number of copies made for a Roman mass market — or sent west by other means:

After the sack of Corinth, with priceless art treasures being piled up on the quayside for removal to Rome (Polybius says he saw soldiers playing draughts on stacks of classical paintings), Mummius—who, as Strabo says with demure wit, was a generous patron rather than an art lover—apparently insisted on retaining one regular clause in his contract with the shipping agency: if any of these objets-d’art were lost or destroyed in transit, they were to be replaced by others of equal value.

The Romans didn’t have much appreciation for artistic innovation or novelty. They liked “conservative, academic, classicizing” art, an “eclectic, sterile (and often mechanical) re-creation of the past.” And for cash, the Greeks were happy to supply it…but there are worse fates than mass-producing the greatest art of yesteryear.

It wasn’t just artifacts. By the first century B.C., the mightiest cities of classical Greece had been reduced to tourist attractions, their populations mere curators for a museum of past greatness. The Spartan agoge, used to train the hoplites who fell at Thermopylae, became a brutally violent spectator event put on for wealthy visitors. Roman elites would do a stint of study in Athens like a British lordling making his Grand Tour to Italy (or like a Chinese scion studying at Harvard?).

For the cities that had once defined civilization itself, it was profoundly humiliating. Yet thanks to the Romans’ new money enthusiasm, the classics endured. They were copied, remembered, and eventually, rediscovered. If the Greeks were no longer relevant, they were at least revered.

I can’t help but think of today. While Western popular culture sinks to lower and lower common denominators, the Chinese are founding dozens of professional symphony orchestras. While we struggle to build anything at all, let alone anything beautiful, Huawei’s vast corporate campus imitates a dozen great European cities.

So majestic was the Greek achievement that, even millennia after their fall, “the extraordinary aura [of Athens] survived, and still survives, all time’s vicissitudes.” Will our own civilization be so fortunate?

The Seventh, it turns out.

Don’t assume that you, the reader, will be free from Green’s scorn. Green studied the classics at Cambridge back when standards were standards. The preface alone includes untranslated phrases in Greek, Latin, French, and even German, a norm that continues throughout the book for the first three languages (and for the fourth in the highly-entertaining footnotes). Green has no patience for the puny monolinguists of today.

Posidonius of Apamea, one of the most famed Stoic writers of the ancient world, was also one of its most famed astrologers.

The Hellenistic Age even had its own version of this: Greek sculptors met high Roman demand by mass producing generic marble bodies that could simply have heads attached to them later — or swapped out, if need be.

Incredibly, it appears to have been common to simply sell off unwanted children directly into slavery.

Roman rule was so unpopular that Anatolian Greeks joined a conspiracy to murder every Roman in the province, and so the violent destruction eventually came anyway.

A shared quality between golden age America and Greece(and Rome, for that matter) is a military meta that prioritized mobilizing large numbers of heavy infantry combined with a level of state capacity that was unequal to the task of maintaining a permanent professional force on that scale. The aristocracy in this situation had to make some concessions to the ordinary citizens who formed the backbone of the army and navy if they wanted to win wars. When state capacity reached the point where a citizen militia is no longer needed, citizens' rights and autonomy were rapidly eroded.

Eras where the meta is prohibitively expensive tech such as cavalry, chariots, or air power favor aristocrats and plutocrats in those societies where state capacity is lacking, so you get feudalism or something like it instead of citizen republics.

Green, incidentally, published fine translations of the Iliad and Odyssey in his 90s, and died just before his 100th birthday. Perhaps spleen kept him going.