REVIEW: Storia do Mogor, by Niccolao Manucci

Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653-1708 (vols. 1 and 2), Niccolao Manucci, (trans. William Irvine, John Murray, 1907).

There are people who say “you can just do things,” and then there are people who at the age of fourteen stow away on an ocean-going vessel heading who-knows-where. Niccolao Manucci was the latter sort, and he held out down in that ship’s hold as long as he could, until hunger got the best of him. In fact, he lasted so long that when he finally gave in and presented himself to the captain it would have been inconvenient and uneconomical to return him to his parents in Venice. As the sailors debated whether to toss him overboard, press him into service, or maroon him on the closest bit of coastline, young Niccolao went and chatted up the other passengers. One of them, Lord Henry Bellomont, had recently escaped death at the hands of Oliver Cromwell, and invited Manucci to accompany him on an important mission to Persia.

That sounded pretty good to the teenager, so he disembarked with Bellomont at Smyrna, made the hazardous journey across Ottoman Anatolia, thence through Armenia, and finally to the Safavid Empire, where Bellomont declared himself an ambassador from the rightful king of England and sought Persian intervention in the English Civil War (!). The Shah was horrified by the regicide and amazed that the other Christian kings of Europe had not come to the aid of Charles I,1 but gently rebuffed Bellomont’s request by pointing out that it would be quite impractical to send a large army from Persia to England.

Frustrated, Bellomont set off once again with his young charge, this time to the Mughal Empire. He got as far as the port of Surat, where he suddenly died, leaving the teenage Manucci completely on his own, thousands of miles from his home, in the middle of a civil war.

I sometimes wonder how often this sort of thing happens without us ever finding out. Perhaps history is full of ridiculous people having ridiculous adventures, it’s just that most of them aren’t Zhu Yuanzhang, or they don’t write detailed memoirs, or those memoirs are lost or destroyed before they reach us. Something like this very nearly happened to Manucci. The Venetian teenager left all alone in India not only survived, but flourished socially and financially, lived to a ripe old age, and wrote thousands of pages of penetrating social observations. His account is both the most entertaining and the most reliable history of the Mughal Empire at its zenith. Manucci had the singular talent of moving through every social circle, from the royal court to the lowest of peasants. He interacted with generals and statesmen, harem attendants, Islamic jurists, Hindu sages, elephant drivers,2 Portuguese mercenaries, eunuchs, merchants, prostitutes, common soldiers, missionaries, beggars, and even the emperor himself. There are very few cases where we get to see a premodern society laid out in all its intimate detail and from every angle, and we only missed losing this one by the barest of lucky strokes.

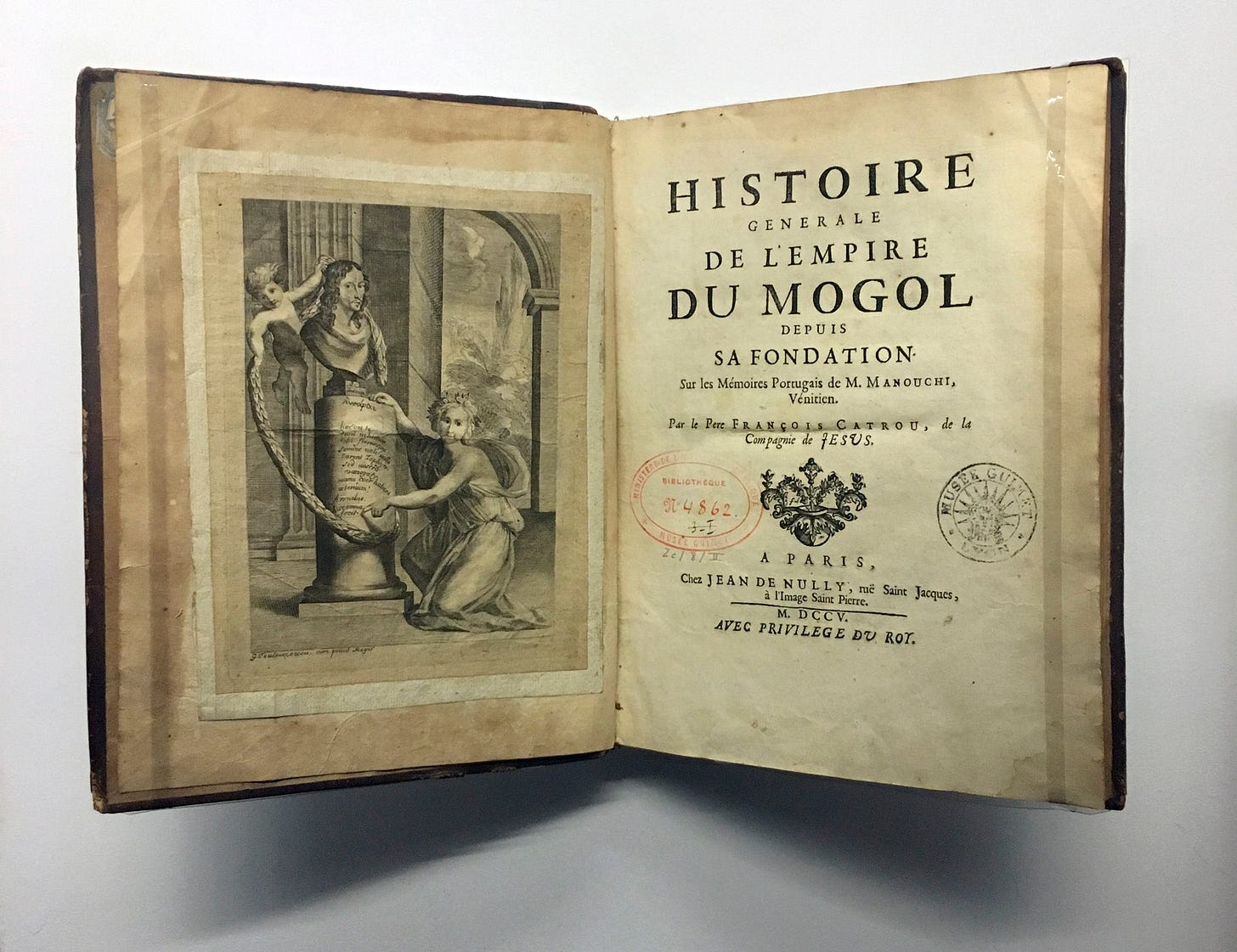

The story of Manucci’s manuscript is a twisting one. The original copies of his tale fell into the hands of a French Jesuit who mutilated the text — excising all the fun parts, all the personal observations, the adventure stories, and of course anything remotely critical of the Catholic Church. The resulting “edition” found its way back to India and into Manucci’s hands before his death. Naturally, he freaked out and tried to reproduce his original text from memory, sending it along with a letter of protest by sealed courier directly to the Venetian Senate. But this second copy is the work of a much older man, much farther from the stories and events described, and has numerous omissions and differences from the original.3 In 1763, the Jesuit order was expelled from France and their Paris library, including Manucci’s first manuscript, was seized by the state. It was then lost during the Revolution and believed destroyed, before turning up in damaged and partial form at an auction-house in Berlin a century later.

Countless European intellectuals have tried their hand at stitching the mishmash of fragments we have back into a cohesive whole, including a “J. Bernoulli” (yes, one of those Bernoullis, but I can’t figure out which brother it was). But everybody agrees the most successful of these efforts was that by William Irvine, a British colonial administrator and fellow of both the Royal Asiatic Society and the Asiatic Society of Bengal, who also helpfully translated the whole thing into English. Irvine’s edition has been republished many times, most recently by the wonderful people at Forgotten Books, which is how it found its way into my hands.4

Irvine is not the sort of editor who confines his remarks to a preface and some footnotes. Instead, he directly injects his own commentary inline, into the body of the text. These asides range from bracketed remarks like “[here I have deleted a coarse and obscene description]” all the way up to essays dozens of pages long containing his reflections and opinions on the text. And this is layered on top of the various modifications and emendations made by French Jesuits and Venetian scribes. All of this gives the book a meta-textual, almost postmodern feeling. It’s a bit like House of Leaves. Sometimes you’re reading Manucci, and sometimes you’re reading three nested layers of people commenting on people commenting on people commenting on Manucci. And the effect is heightened when you suddenly realize that Manucci, like the protagonist of a Gene Wolfe story, is not telling you all that he knows.

How do I know that? Well let’s return to the teenage Venetian, suddenly orphaned of his foster father: “I was left alone, sad and anxious, having nothing to console me, nor anywhere to turn in order to recover my things.” Then things go from bad to worse: two other Europeans show up and steal the rest of Manucci’s stuff and coerce him into traveling with them to Delhi. But then somehow the young man scores an interview with the king’s vizier and, using the bits of Persian he picked up along the journey, convinces him to arrest the men who’d tried to abduct him. He parlays the vizier’s friendship into a royal audience, and thence into an offer of employment from the crown prince. In a short while, Manucci is a courtier hanging around the palace in fine clothes paid for by the state, getting tutored in Indian languages and Mughal history and correct deportment. He tells us that the only difficulty in his life was the need to constantly scheme in order to avoid being forcibly converted to Islam, and then interrupts his own narration to give us a few hundred pages of ancient Mughal history.

Are you rolling your eyes yet? Every bit of this story so far, starting from the moment he snuck onto that ship, is literally unbelievable. Irvine certainly seemed to feel that way, if his footnotes and interjections are anything to go by. He evidently flung himself into a centuries-later posthumous cross-examination, looking for any detail in Manucci’s narrative that’s out of place. He doesn’t find any. Worse, he finds numerous corroborating accounts in other contemporaneous sources. But if this story actually happened, then we are left with a nasty trichotomy. One of three things must be true: (1) Manucci is the luckiest sonofabitch alive. (2) Manucci has superhuman powers of persuasion. (3) Manucci is leaving out something important. Actually, I’m pretty sure it’s a little bit of all three, because Manucci is a player character.

They walk among us. Lately the preferred jargon term has been “agency.” Before that people called them “live players.” In the old days they were referred to as “great men,” but that one’s my least favorite of the descriptors because it implies that they have to be like Cyrus the Great or Napoleon, when in reality they’re often much harder to spot. That’s because, as Samo Burja notes, player characters often deliberately cloak themselves in order to avoid detection by other player characters. These ones you may only notice by their aftereffects, like the lingering gravitational distortion after a singularity has whizzed by, reality warping as they knife through to their destination and then reconstituting itself behind them.

Humanity’s great sages have long known that every so often the planets are in a particular configuration, and a Child of Destiny is born. The real question is why. The fun-ruiners will note that in a world of billions of people, some of them are just going to be 6σ lucky. It is difficult for us even to conceive what it means to be 6σ lucky, and yet, like some bizarre object conjured by a non-constructive mathematical proof, we know such people are out there, somewhere in the wave function. But let’s not be fun-ruiners for a moment and consider the other possibilities. Maybe these individuals are chosen by God, or the gods. Or maybe they are the ones paying for the simulation, and therefore have access to the root login. Whatever their source, they exist. Often they spend part of their lives unaware of their true nature. And then…they awaken.

There was a little while when “NPC” was getting thrown around as a term of abuse, but as I have explained at some length,5 there’s nothing wrong with being an NPC. We come by it honestly. At some point, in the Springtime of your life, you bumped up against the universe, you pushed the boundaries, you pushed your limits. On that day, the universe pushed back. Hard. You learned your lesson, like a little kid who touched a hot stove. NPCs are formed from scar tissue, a fibrous mass of tough lessons about the nature of the world. But, as we have just deduced, there must exist people who, whether by divine ordinance or fluke of probability, had a very different experience on that fateful day. They pushed against the universe, and the universe gave in and gave them everything they wanted. And what lesson does that impart? Something like: “Rules are for the sheep, but you can hack the matrix and get what you want.” Now they are awakened. And the crazy thing is that if you keep getting lucky, not 6σ lucky, but just on-a-roll lucky, the awakened state can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Some parts of the world really can be hacked with a little luck and a lot of determination. So there’s a feedback loop that can rapidly amplify mere one-in-a-billion luck into miraculous, reality-altering luck. That’s my attempt at a purely naturalistic explanation of player characters. Or maybe they’re just chosen by God.

Manucci is a slippery one. I only caught him because I read the first part of this book twice: once when I was reading it through casually, and then again as I sat down to write this review and tried to figure out how the hell to convey all this. Again, as with a Gene Wolfe novel, to understand the beginning you must have read the ending. In all the thousands of pages of narration, the one subject Manucci barely touches on is himself. That’s because Manucci is a player character practicing very high-level obfuscation techniques. This sort of misdirection is also the hallmark of a con-man, and what do you know: there is one brief, brief moment when Manucci gets a little too sure of himself and lets slip that he actually was functioning as a super-effective con-man back there in 17th century India. He wove his web of shadows around the Mughal aristocracy, and then he nearly got it around us the readers as well.

So we finally have Manucci pinned down: he is the subtype of player character known as a “guile hero.” You know them from stories: Odysseus, or Locke Lamora, or almost every character played by Kevin Spacey. Manucci is like them, his character class is either rogue or bard.6 At what age was he awakened? Was he already aware of his powers when he crept down that Venetian dock? And what really happened between him and Bellomont? Did he seduce the English gentleman? Or did he suss out his mission and blackmail him with a threat to make it public? Or did he just turn the full force of his personality on the hopeless cavalier and get 6σ lucky on his CHA roll? We shall never know. But if you are asking questions like these, then you now have the correct interpretive lens for what follows.7

Anyway, this is the point in the book where Manucci avoids our questions by launching into a scholarly disquisition about Mughal history (when he restarts the story it will be in medias res, and ten or twenty years will have passed).8 Irvine hates this section, describing it as “nothing more than a farrago of the wildest and most improbable legend,”9 and his footnotes and interjections only escalate in violence from there. But it’s fun. Manucci starts with Tamerlane, the last and most brutal of the great steppe conquerors, and gives abbreviated and fantastical biographies of all his nasty descendants through Babur, the invader of India and founder of the Mughal kingdom.

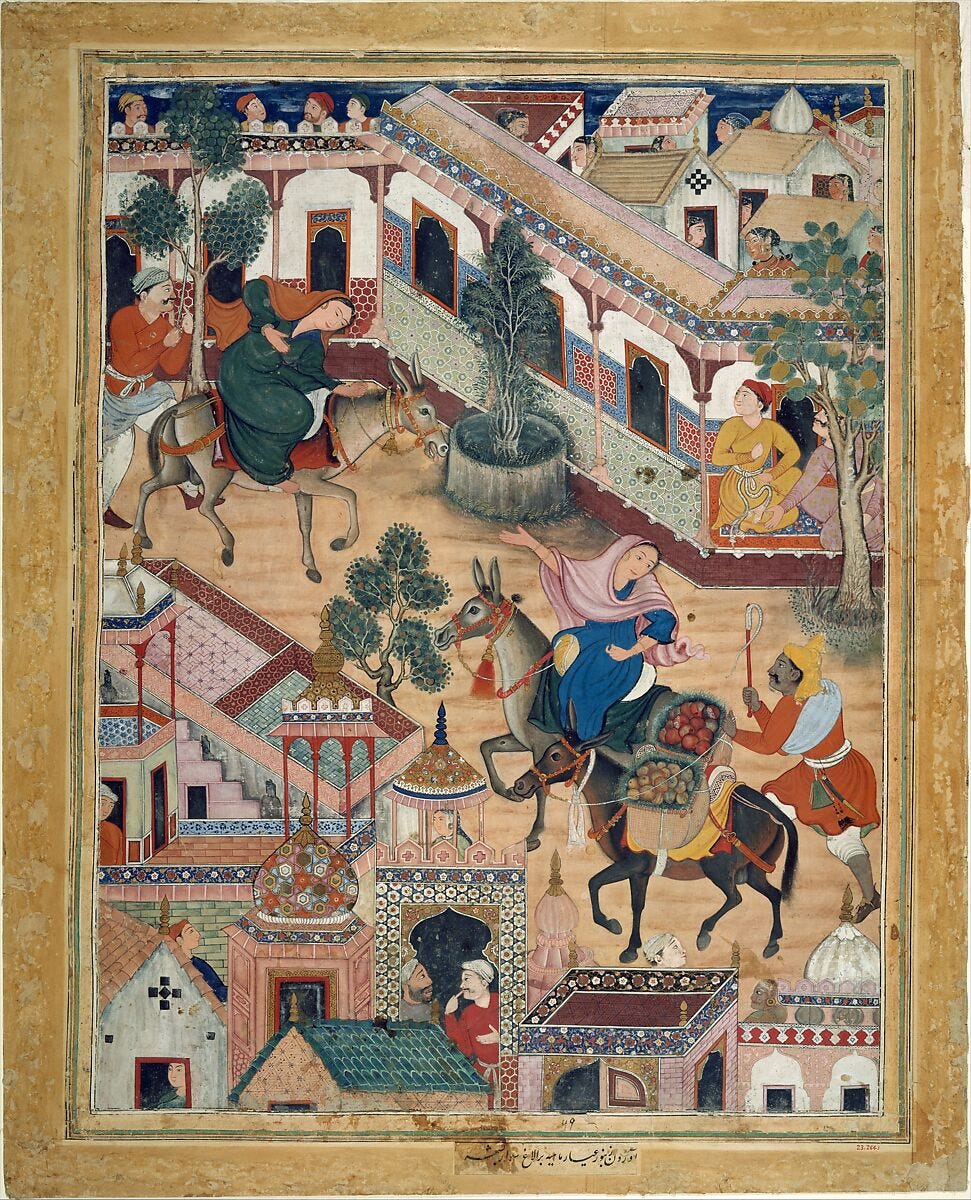

At this point, the biographies start getting much lengthier and filled with stories which, if not true in the sense of “actually happened,” are probably true in the sense that they convey import context and setting material about the world he’s about to plunge you into. They are also fun. Like the king who accidentally sends his best counsellor into hiding, and in order to locate him proclaims a ridiculous and self-contradictory law, and then sends troops to the only podunk village that wrote back with a reasoned and cogent objection.10 Or the queen who — when her royal city was about to fall to the Mughal king Akbar — ordered all of the gold to be melted down and formed into cannonballs that were fired in all directions to deny him loot.11 Or the king who ordered that an entire palace be built out of copper, but abandoned the plan when they ran out of metal (and when they discovered that in the summer it would literally be a giant oven).12 Or the king who lined his roads with vast pillars of rebel heads, and would swap in fresh ones as they decomposed.13 Or the European artilleryman who won the right for other European mercenaries to distill and drink their own liquor by deliberately missing all his shots when sober.14 But my favorite is the king who was obsessed with the question of what language a child would innately speak if never taught a language by another:

[The king] ordered the erection of a house with many rooms at a distance of six leagues from the city of Agrah, and directed them to place in it twelve children, who should be retained there to the age of twelve years. An injunction was laid on everyone that, under pain of death, no one should speak a word to them or allow them to communicate with each other. This was done, because one set of men asserted that they would speak the natural language, that which was the language of our first parents. Others held that they would speak the Hebrew language; others that they would not speak anything but Chaldean; while the Hindu philosophers and mathematicians asserted that they must infallibly speak the Sanskrit language… However, the twelve years having passed, they produced the twelve children before the king. Interpreters for the various languages were called in to help.15 Each one put questions to the children, and they answered nothing at all. On the contrary, they were timid, frightened, and fearful, and such they continued to be for the rest of their lives.

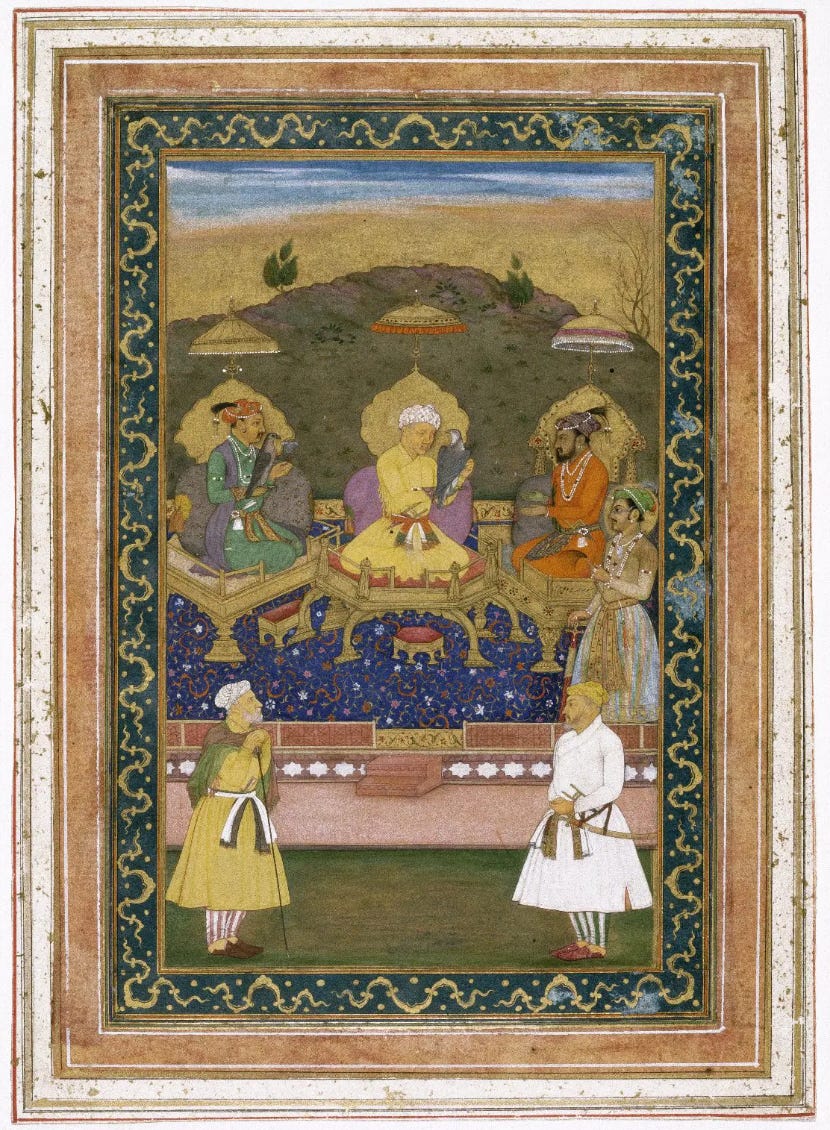

This brings us to the first of the kings that Manucci knew personally, the father of that crown prince into whose employment he so improbably entered. This king was Shah Jahan, whom you may know as the founder of the city of Delhi and builder of the Taj Mahal. Here, Manucci’s tone unmistakably shifts. We have left the realm of history and legend, and are now dealing with people that he knew personally and intimately. But even when Manucci is describing the most loathsome people, he can’t help enjoying their company. His portraits sometimes get judgy or catty, but always in a sort of bemused way. He can’t help liking these people, and that comes across so clearly that I in turn can’t help liking him.16

Shah Jahan famously built the Taj Mahal in a romantic gesture to honor his dead wife, but what’s less well known is that he went on to have one heck of a rebound. As the Sultan of Hindustan and King of the Kings of India, he had a harem full of thousands of eager women, yet he gradually destroyed his kingdom by repeatedly seducing or raping the wives of his most faithful advisors. Even this was not enough to satisfy his libidinity, and he established an annual fair where, for eight consecutive days, all men besides the king were expelled from the palace and tens of thousands of women of all races and nationalities were locked inside, while he toured them with his female attendants like a vast meat market.17 The most attractive women might be admitted to the royal goon cave:

For the greater satisfaction of his lusts Shahjahan ordered the erection of a large hall, twenty cubits long and eight cubits wide, adorned throughout with great mirrors. The gold alone cost fifteen millions of rupees, not including the enamel work and precious stones, of which no account was kept. On the ceiling of the said hall, between one mirror and another, were strips of gold richly ornamented with jewels. At the corners of the mirrors hung great clusters of pearls, and the walls were of jasper stone. All this expenditure was made so that he might obscenely observe himself and his favourite women.

Shah Jahan had other qualities (for instance, he kept a basket of poisonous snakes by his throne and would have them bite people as a form of execution, and he liked to punish his officials by placing rats down their daughters’ pants), but his total slavery to his lusts seems like the most important one, since he eventually blew up his kingdom over it. But the crazy thing is that while Shah Jahan may be the most extreme representative of “harem culture,” he was far from an outlier. Unlike pretty much any other European traveler, Manucci got to visit the insides of harems often, initially just because of player character energy and later on because he was pretending to be a doctor (oh yes, we will get to this). His reports are grim.

You have to understand that Manucci is very far from a 21st century feminist. I dare say, he is not even a 17th century feminist. And yet even he is totally disgusted and horrified by the reality of the harem once all the orientalism and fantasy is stripped away. A Mughal gentleman would have, depending on his rank and wealth, between a few and a few thousand18 young women locked up and guarded in a special compound. No other man was permitted to enter, so the women on the inside were guarded and waited upon by a combination of eunuchs and elderly matrons. If you were low-ranking, your harem might just consist of foreign slaves and daughters of farmers and peasants. If you were the king, you’d have some of those (if they were exceptionally beautiful), but also princesses and noblewomen from rival kingdoms, or the relatives of your own courtiers.

What shocks Manucci the most, I think, is how this completely destroyed trust between the sexes. The women are property. But they’re treated as fundamentally untrustworthy property that’s looking for any opportunity to “dishonor” the master of the harem by sleeping with anyone or anything else.19 Likewise, every Mughal man assumes that every other Mughal man is constantly attempting to break into his harem and ravish his nubile toys (granted, when Shah Jahan is around this might not be an inaccurate assumption). Yes, the harem is fundamentally about easy sex on demand, but it also weirdly rhymes with prepper fantasies about home invasions. The harems all have elaborate and over-the-top security procedures (not least the thousands of men who are castrated to be able to serve as guards). One gets the sense that the owners have almost as fun dreaming up and foiling ways of breaking in or out as they do with the ladies.

Meanwhile the women on the inside just sort of waste away mentally. Some of them drink a lot or do a lot of drugs, others try to outcompete each other in sluttiness when the master visits in the hopes that they will bear his children. Still others spend all their time scheming against the other women, or playing abusive tricks, or plotting how to sneak out or sneak their boyfriends in. Manucci has a few “regulars” who pretend to be sick so that the famed European doctor (no, he is not actually a doctor!) will be called in and they can…feel the touch of his manly hand when he takes their pulse. Is that all that happened? I rather doubt it, but Manucci doesn’t kiss and tell.

Most of the previous paragraph applies to Shah Jahan’s daughters too. Unlike the other women in the harem they did not belong to any man, but like them they were kept confined without family or purpose. Shah Jahan did not permit his daughters to marry, in keeping with ancient Mughal policy that the king ought to avoid having sons-in-law. The eldest, Begam Sahib, was her father’s favorite and had her own palace outside the royal court. She was a factional ally of the prince who was Manucci’s employer, and as an unmarried woman she was technically supposed to live in her father’s harem, so she maintained a large staff there that fed her palace intelligence. A lot of that intelligence then made its way to Manucci, who was close friends with her chief eunuch and a number of her maids. Begam Sahib led a scandalous life, and flaunted her many lovers and her use of various drugs. She was also fond of booze (which was illegal in the Mughal empire):

But the best liquor she drank was distilled in her own house. It was a most delicious spirit, made from wine and rosewater, flavoured with many costly spices and aromatic drugs. Many a time she did me the favour of ordering some bottles of it to be sent to my house… This liquor profited me greatly. The lady’s drinking was at night, when various delightful pranks, music, dancing, and acting were going on around her. Things arrived at such a pass that sometimes she was unable to stand, and they had to carry her to bed. I say this because I was admitted on familiar terms to this house, and I was deep in the confidence of the principal ladies and eunuchs in her service. I have no wish to state all that went on.

The next oldest child was Manucci’s patron, the crown prince Dara, “a man of dignified manners, a comely countenance, joyous and polite in conversation, ready and gracious of speech, of most extraordinary liberality, kindly and compassionate.” Prince Dara was also something of a xenophile: he loved Europeans, proclaimed himself agnostic on all religious questions, and enjoyed hosting and debating Christian, Jewish, and Hindu scholars.20 But his most important trait was a fondness for absurd practical jokes that made everybody at his father’s court hate him. Prince Dara was constantly ridiculing and humiliating all of his father’s generals and councilors (who, remember, were already reeling from the need to protect their wives and daughters from Shah Jahan). Manucci ends his description of Dara’s character with: “He might have been King of Hindustan if he had known how to control himself.”

We will breeze over the next five kids: two sons, who commanded armies in the field and nursed a festering resentment against their father and older brothers; three daughters, who lurked in the harem with smuggled-in boy-toys, and each allied with a different brother and fed them intelligence. But then… there was also one more son.

In 1653, a most curious omen was reported from the city of Rajmahal in Bengal:

At eight o’clock in the day there appeared near the said city, in a plain a league and a half broad, a great number of cobras, large and small. They covered the field and moved from West to East until four o’clock in the afternoon; they looked like ripples in the ocean. In the greatest fright, the inhabitants of the villages climbed upon the tops of their houses and upon trees. They beheld moving in the midst of the said cobras one of great size, which carried on its head another smaller one, entirely white.

Everybody consulted astrologers, and they got a lot of different, bad answers. They agreed that the small cobra riding on top of the giant one must be the King of All Cobras, but gave conflicting interpretations as to what that meant. Probably they just wanted to avoid the obvious one: there was already somebody in Hindustan nicknamed “the White Snake.” It was Prince Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan’s middle son, so named because he was pale of skin and slight of build and made everybody around him uncomfortable. Shah Jahan hated him because he was weird looking and because when he was a child a holy man had prophesied that the White Snake would destroy his family’s legacy.

When you’re born with the deck stacked against you like that, you have to get creative if you want to survive. Aurangzeb was a survivor. The first order of business was obviously to remove himself as a contender for the succession before he got arrested or poisoned. He accomplished this by becoming a wandering mendicant and ascetic, renouncing all earthly status, traveling to Mecca, and becoming so learned in Islamic law that people acclaimed him as mullah. The second order of business was to begin building his power base in the provinces, because the whole first order of business was a sham. So he did favors for the most important of the Mughals’ vassals and client states, led some successful military campaigns, and captured a large number of cannon which he stockpiled in his home base of Aurangabad.21

What does not seem to have been a sham was his asceticism or his religious conviction. I need to harp on this, because he initially pattern-matches our modern stereotype of a bad guy who cynically uses religion to his advantage. No, it’s more complicated than that. He was a bad guy who cynically used religion to his advantage, but his Islamic fanaticism was simultaneously 100% sincere. He also hated alcohol. As a young man Aurangzeb had a dalliance with a dancing girl who liked to drink. She died suddenly, which the prince interpreted as a sign from Allah pointing him towards a new and glorious path. Perhaps it was just that simple. Or perhaps, as Dr. Freud might suggest, the black sheep of a family permeated by harems and drugs and booze would naturally incline the other way.

So there you have the Mughal Empire under Shah Jahan and his four sons and four daughters, sitting around like an enormous pile of dry tinder perched on top of a powder keg. The crisis when it came was precipitated in a very Shah Jahan way. You see, he was sixty-one years old, and when a man gets older sometimes his sexual performance with his two thousand harem girls begins to falter. He sought potions and tonics from every corner of his kingdom, and one of them solved the problem a bit too well. The resulting erection lasted for three days, during which time he was unable to urinate effectively, which led to a bladder infection that soon had him on death’s door.

In fact, Shah Jahan recovered from his illness very quickly. But in those days, news traveled slowly, and everybody was already on a hair trigger for the inevitable succession war when the old man died. So while Shah Jahan’s fever raged, Dara began mustering an army, and when news of that (and exaggerated rumors of Shah Jahan’s condition) reached his brothers, they one by one declared themselves in rebellion on the flimsiest of pretexts. A few days later, when a new messenger arrived announcing that the king had recovered and demanded their submission, it was too late to walk things back. Everybody saw where they and the others stood. It was time for war.

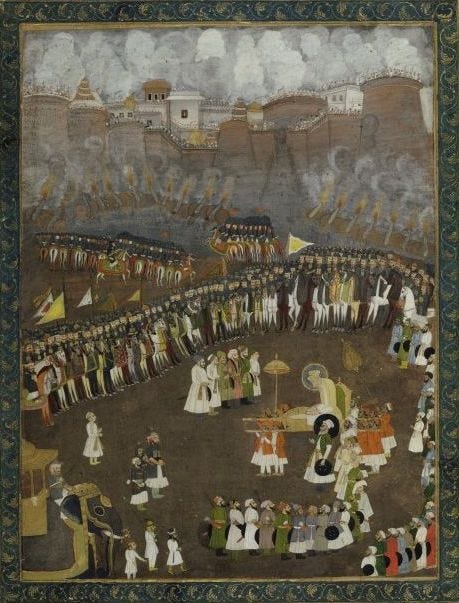

If you’re genre savvy, you know how this ends. The civil war was an absolute curb stomp in which Aurangzeb annihilated the combined forces of his father and brothers. First he used his reputation as a humble Islamic scholar who’d renounced all claim on the throne to worm his way into the confidence of his brother Murad Baksh. He then magnanimously offered to lead his army for him, which turned out about as well as you can imagine for Murad Baksh.22 He consistently out-strategized, out-planned, and out-fought the others. He used poison and assassination to remove their closest confidantes. He bought off their top generals and advisors (who, remember, already hated this family because of Shah Jahan’s predatory behavior), and if he couldn’t buy them off then he played weird mind games to make his opponents think that he’d bought them off. In the case of one brother, literally every honest subordinate got exiled or executed for conspiring with Aurangzeb, and every remaining subordinate was actually conspiring with Aurangzeb. He went into battles outnumbered, and emerged with barely a scratch as the opposing army evaporated on contact due to backstabbing amongst its leaders and panic amongst its common soldiers. And the more he won, the more others were scared to face him.

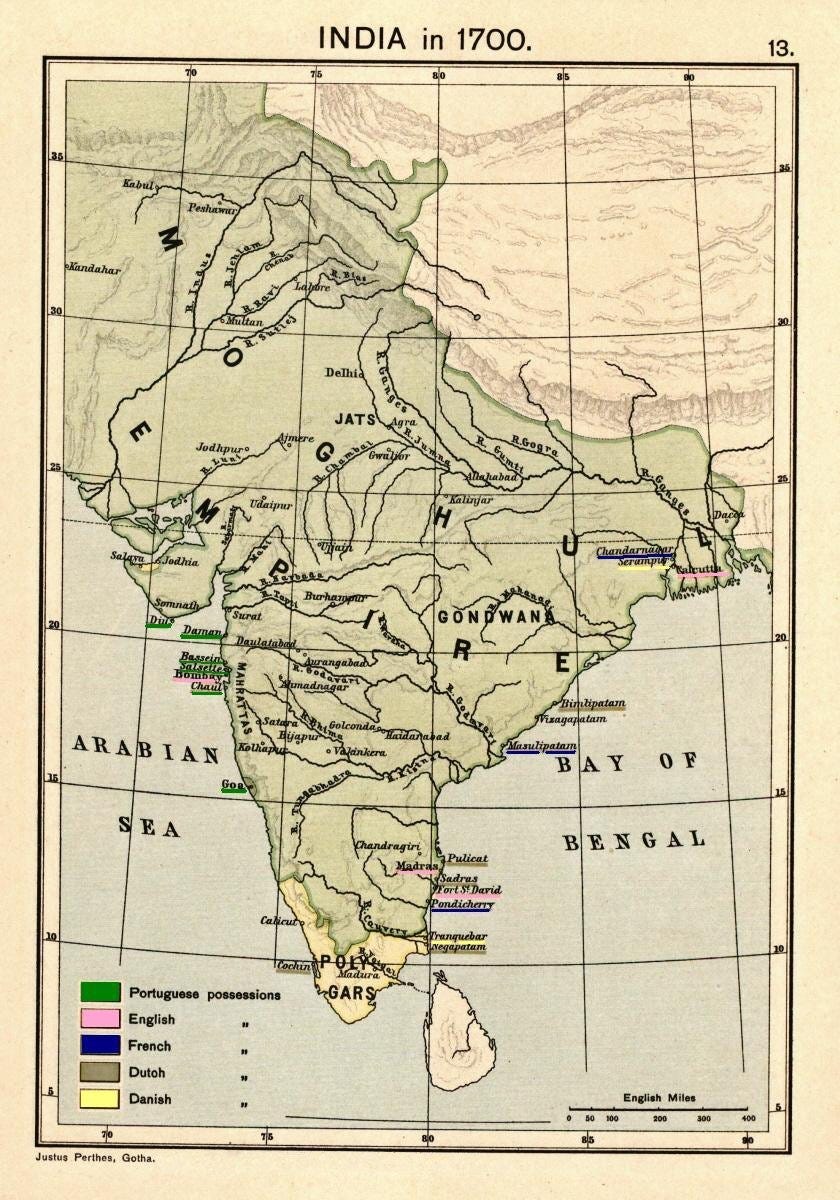

This is the moment at which Manucci suddenly reenters the story, as a leader in Dara’s army in charge of a band of European mercenaries. All of the brothers employ huge numbers of white mercenaries, mostly Portuguese,23 mostly either as artillery specialists or as elite shock troops. The Europeans are valued for being more violent and more disciplined than the Mughal troops or their Indian allies, and also for being much less likely to run away. The Mughal armies are huge, but they’re mostly mobs of untrained peasants who treat war as a fun outing and refuse to attack without overwhelming numbers.24 The Mughal commanders are warrior aristocrats who love to display their martial prowess and act chivalricly. The Europeans, by contrast, are just professional killing machines who neither run away nor get overly hung up on niceties.25

The first battle that Manucci describes from ground level was lost by Dara because of a dumb decision and some bad luck. The prince was personally leading his vanguard from atop a great war elephant, and the initial shock of their charge caused part of Aurangzeb’s army to falter and retreat. To mop them up, Dara got down off his elephant’s back and onto a horse to run them down, but as soon as he did a rumor began to be spread that he was dead, and nobody could refute it by looking up and seeing him on the elephant. A weird mirror version of this happens in a later battle when one of Aurangzeb’s elephant-riding generals is killed by arrow fire, but a loyal servant prevents the army from panicking by crouching behind the corpse still in its howdah, and turning its head and moving its arms like some grotesque human puppet show. Since I apparently cannot resist drawing glib leadership lessons from these book reviews, let me just say that an important one is “always stay on your elephant” (ὁ ἀναγινώσκων νοείτω).

Dara gets beaten in battle after battle, but Manucci’s star just keeps rising and rising. Say it with me now: he’s a player character. Manucci keeps recounting meetings where the prince says something like, “well, we got totally destroyed out there and I don’t know how much longer we can hold on, but you’re just so awesome, Niccolao, so I’m doubling your salary and giving you an extra-cool turban.” It’s a good example of how you can’t let Manucci cast his glamor over you, but need to maintain a suspicious and hostile mind while reading (this is one thing Irvine gets right). So while it’s objectively true that Manucci’s rank in the Mughal civil service26 was rising at this time, I interpret these episodes as being 50% real and 50% fluff. The funny thing is that Manucci was trying to make himself look good to his readers, but he accidentally makes himself look good…at manipulating Dara.

I am glossing over a tremendous amount. Manucci spends hundreds and hundreds of pages on this civil war. There are crazy hijinks along the way. A lot of it is Manucci engaging in deranged player character behavior, of course, but not all of it. Dara’s wife is a colorful character who is constantly threatening suicide, then does things like feed tribal chiefs the water she used to wash her breasts to emasculate them and symbolically turn them into her children. As his odds grow longer, Dara turns to supernatural assistance and recruits holy men to petition Muhammed in paradise and request his intervention. The holy men go away and give it a try, then come back and dejectedly report that Muhammad is busy. Busy? Yes, busy, Aurangzeb is talking to him nonstop, and as a result their messages cannot get through.27

As the war draws to an end, Aurangzeb captures the capital and Shah Jahan, then in a bit of ironic contrapasso imprisons his father together with his harem in a palace that overlooks the Taj Mahal — the monument to his dead wife. He likes to humiliate his defeated enemies and make them suffer, especially if they’re his family members. At one point he doubts the loyalty of one of his own sons, and has him confined to a dungeon, and orders the jailers not to allow him to have or even overhear any human communication, and “to ply him continually with the water of opium until his mind was destroyed.” When he has Dara cornered, he announces his intention to make Dara’s wife into his concubine, which drives her to such despair that she finally does kill herself. On finding her corpse, Dara is a broken man, and barely resists as Aurangzeb’s soldiers put him in manacles and drag his children away.

Aurangzeb, who has now occupied the royal palace in Delhi, orders that Dara be forced to process through the main streets of the city as a prisoner. At one point a homeless beggar calls to him: “O Dara! When you were master you always gave me your alms; today I know well thou hast naught to give me.” Dara tries to give the homeless man his cloak, but is punished because he is lower than the beggar and has no right to give anything. A short while later, Dara is beheaded, and a gloating Aurangzeb stabs the head through the face, then orders that a feast be prepared, and that the head be cleaned up and sent to Shah Jahan’s prison.

[He] waited until the hour when Shahjahan had sat down to dinner. When he had begun to eat, I’tibar Khan entered with the box and laid it before the unhappy father, saying: “King Aurangzeb, your son, sends this plate to your majesty, to let him see that he does not forget him.” The old emperor said: “Blessed be God that my son still remembers me.” The box having been placed upon the table, he ordered it with great eagerness to be opened. Suddenly, on withdrawing the lid, he discovered the face of Prince Dara. Horrified, he uttered one cry and fell on his hands and face upon the table, and striking against the golden vessels, broke some of his teeth and lay there apparently lifeless… Then I’tibar Khan removed the head. When the old man recovered consciousness he began to pluck out his beard till it was all bleeding, and to beat his face; then, dissolving into a flood of tears, he raised both hands to heaven and said these words… “My God, Thy will be done.”

As a final insult, Aurangzeb dug up the sepulcher of the Taj Mahal and dumped Dara’s headless corpse into it, so that every time Shah Jahan looked out the window at the memorial of his dead wife, he would remember his murdered son, and so that the one sight out of his prison would never bring him peace or joy again.

But this was still just a warmup. Next Aurangzeb took Dara’s surviving wives and forced them to become his concubines, then had all of Dara’s children secretly murdered, and then launched a wide-ranging and ruthless purge of all Dara’s associates and allies. Manucci barely escapes with his life, but is eventually captured and presented to Aurangzeb who (naturally) offers him employment because he is a player character. Game recognize game, after all. But here Manucci does something most out of character, and politely declines. He has had enough of politics, and wants to go see the world. So he heads for the Indian coast and leaves Aurangzeb to quietly complete the slaughter of his entire extended family.

This section of the manuscript is one of my favorites, because we finally get to spend some time with Manucci, and he’s the one character I kept wanting to get to know better. When he’s writing about history and war and grand affairs of state, it’s very easy for him to fade into the background. But when he’s writing about his own travels and mundane events, even though he’s practicing the arts of obfuscation, he necessarily stands out a bit, and occasionally lets important things slip. For example, that he has agents placed in every major palace and royal apartment… How odd! Could it be that he was more than an adventurer and mercenary and former companion of the former prince? And then, almost five hundred pages into this book, he mentions that he was short on money and so went to collect payment from the Viceroy of Goa who owed him for “certain articles that he had asked me to send him when I was in the Mogul country.”

Yes, we finally got there: Manucci was a spy. Suddenly a number of mysteries are cleared up, like why he’s so well-informed, and why he collects favors from seemingly every dancing girl and scullery maid in Delhi, and why he’s so good at disguises,28 and why mysterious assailants keep randomly attacking him. Presumably somebody found it very useful to have him in the Mughal court, until things got a little too hot with Aurangzeb’s accession, and he decided to bail out. But how long had he been a spy for? And who was he spying on behalf of? Were the colonial authorities in Goa his main employers, or was that just a bit of freelancing? None of these mysteries have obvious answers, just like he never comes out and says, “I was a spy.” But if you interrogate the book, if you read it critically, I bet the answers are there.29 Manucci never covers his tracks perfectly, and besides I think on some level he wanted to be caught by his readers.

So we get to travel around 17th century Southeast Asia with him, while Manucci hitches rides on boats, battles crocodiles and pirates, makes careful sketches of port facilities… He even almost gets married a couple of times. And I know as I write this that I am merely falling under his spell like all those others did centuries ago, but gosh darn it I really like him. He’s friendly, and intellectually curious, and brave, and has a wonderful deadpan sense of humor. He is very smart, as evidenced by his command of almost a dozen languages, and he is also streetwise and rarely caught flat-footed. He assumes the best of everybody he meets, while always being prepared to unleash savage violence on them. And he has moments of real moral seriousness that you don’t quite expect from a sellsword and a charlatan and a rogue.

This is also the section where Manucci lets slip that he is a Catholic, and not just in the sense that everybody in 17th century Venice was a Catholic. The first clue is when he mentions offhand taking an extremely inconvenient detour on one of his voyages so that he can spend Lent in a town that has a church.30 Another hint comes via omission: this man is a spy, his morals are highly flexible, and he pretends to be many things he isn’t. But in all his escapades, he never denies Christ and never pretends to be a Muslim or a Hindu, even when that would make his life far more convenient.31 In one episode, we even get a foreshadowing of a modern Irish joke (which makes me wonder just how old that joke is!):

I fastened my gown or qaba on the right side, as is the fashion of Mahomedans. The Hindus fasten theirs on the left. I also went with my beard shaven, wearing only moustaches like the Rajputs, but without pearls hanging from ears as they have. The Rajput officers wondered at this get-up, neither Rajput nor Mahomedan. They asked me what religion I belong to; I replied that I was of the Christian religion. Once more they asked me whether I was a Mahomedan Christian or a Hindu Christian.

But the dead giveaway that he really believes in this stuff is his absolutely incandescent anger at priests and missionaries who by their conduct give the faith a bad reputation. There are a lot of these, and Manucci does not hold back in laying out their crimes (these are some of the most heavily censored sections of the French edition, and had to be patched up with the Venetian codices). Why would it be that this guy who has spent decades observing every sort of depravity only really loses his mind when he sees a corrupt priest? He is a mercenary who has waded through lakes of blood, and jaded to the point where he can describe even the most senseless massacre in a wry manner. But a hypocrite priest is betraying the One Good Thing that Manucci still believes in, something pure and perfect and beyond the grasp of this world, something that can never be pillaged or butchered or raped or despoiled.

All of this makes Manucci an even more perfect foil for Aurangzeb. Just as we are not used to the idea that a bloodthirsty dictator who lies and cheats his way into power might be a sincere believer, so we are also not used to the idea that a roguish, cunning, deceitful anti-hero might be dutifully saying his prayers every night. Neither one computes, but that’s because we expect people to be easy and simple. In reality, people are complicated. Manucci’s writing practically aches with religious longing. At one point he describes the martyrdom of a friar who apostasized, converted to Islam, and then returned to Christianity despite knowing that it would lead to his torture and death:

God avails Himself many times of men’s sins to exalt them, and to show that, although to some it may appear that He has forsaken them, He may yet save us as long as we are still alive.

I don’t think he’s just talking about the friar.

Speaking of Aurangzeb, how is the new King of Hindustan settling in?32 Pretty well, in fact! In a few short months, Aurangzeb launched sweeping crackdowns on alcohol, hashish, and musical instruments. Then he forced all dancing girls and prostitutes to marry. After that he kicked off a pogrom against his Hindu subjects by poisoning or arresting most of his Hindu courtiers, then banning their religious festivals, and then sending out an army to smash and desecrate every famous temple or religious idol within reach.

You might wonder how popular this all made him. The answer is “very popular.” He still sometimes wore the garb of a wandering ascetic, and many of his subjects were sincerely convinced that he received prophetic visions. Aurangzeb encouraged this belief by installing an all-seeing network of spies and informers, who told him all kinds of random facts about random people, which he then used in public demonstrations to appear omniscient. Even the people who didn’t like him believed that he was a great and powerful sorcerer, and he became known as “the miraculous king.”

A sign of how total his grip on the empire was is the reaction when Aurangzeb got very sick. As you will recall, an illness was the trigger for the rebellion against Shah Jahan’s rule. But in Aurangzeb’s case, all his children and vassals and courtiers sat terrified and well-behaved while he ailed, because they all assumed it was just a trick to smoke out traitors. Nobody dared to plot against the guy who was so fiendishly good at plotting. He had creative solutions to domestic problems too, like forcing disobedient daughters to marry their imprisoned brothers, so that they couldn’t legally run off and marry somebody else and produce a legitimate claimant against him. Of course Shah Jahan was still locked in his harem, but that was only a problem for a little while longer:

One day Shahjahan was in front of a mirror adjusting his moustaches, and these two women were standing behind him. One made a sign to the other, as if mocking the old man who wanted to get himself up as a youth. Shahjahan saw the gesture, and, touched in his reputation, had recourse to drugs to maintain his strength in his accustomed vices. By these his bladder was so weakened that a retention of urine came on. For this no remedy could be found, he being now an old man and much enfeebled.

And so Shah Jahan died as he lived.

As the new king was settling in, the old scholar who had been his childhood tutor heard about his accession and about the propitious start to his reign. The teacher made the long journey to court to present himself and to receive the gratitude (and surely also a financial reward) from his former student. Instead, Aurangzeb publicly humiliates the old man and accuses him of only teaching useless and impractical lessons. He rages at him, “You should have told me how to gain friends, to take or besiege fortresses, and fight pitched battles.”

And he has a point. While some more fortunate princes are taught these lessons systematically, Aurangzeb is truly a self-made man. His royal upbringing was as much an obstacle to the throne as a stepping-stone, insofar as it made him a prime target for assassination his entire childhood. He doesn’t even look like his father and brothers, are we even sure he’s really his father’s son? Everything that got him here — his craftiness, charisma, knowledge of poison, skill in battle, his talent for instilling fear and commanding obedience — it’s all self-taught, all learned on the job during an adolescence that was one protracted struggle for survival and then supremacy. And if, as we might suspect, the “white snake” is not actually of the blood of Tamerlane, but a bastard sired by a commoner who snuck into Shah Jahan’s harem, then he is truly one of the all-time great rags to riches stories. Dare we even say…a player character?

Could it be? What are the odds that there were not one, but two player characters running around the Mughal Empire in the 1650s, and that one of them became the king? But on the other hand, if we examine Aurangzeb’s career less historically and more novelistically, he is clearly the sort of dark and edgy villain protagonist that you love to hate.33 So is Manucci actually the main character of this story? Or is it Aurangzeb, and Manucci is just the unreliable narrator who crosses paths with him? Some may resist the idea of this psychopathic monster as the main character of 17th century India, but Manucci has no time for that:

Those are kings whom God appoints, but as they know not His secret purposes, men decline to acknowledge those who unjustly seize some kingdom. All the same, the saying in the Proverbs of Solomon, chapter viii., is incontrovertible: Per me reges regnant. God alone raises men to the throne to be either a scourge or a solace to their subjects.

And it clears some things up, like his insane runs of luck, and like the fact that he played the game on a completely different level from all the other contenders. There are people who sort of sleepwalk through life, and there are people who treat every situation they’re in as a scenario in a game and then work out from first principles what the optimal actions are for winning the scenario. Manucci and Aurangzeb are strange mirrors for each other in one more way: at times they seem like the only guys who are really trying.

If we can’t admire Aurangzeb morally, we can at least admire him aesthetically. There is something darkly beautiful about watching somebody so lethally ambitious and unprincipled at work. He may be a bastard (in both senses), but he is a magnificent one. He is the villain whom we can’t help chuckle with as he stays one step ahead of the hero. He’s something dangerous and powerful, like a shark on the hunt, which we enjoy watching so long as we can stay out of its way. No doubt Manucci sensed it too, which is why he turned down that generous offer of employment. Player characters usually try to avoid each other after all. We can only conclude that for all his powers of observation, Aurangzeb didn’t notice Manucci’s true nature. A good thing too, since if he had, Manucci probably would not have survived to write this book.

Deprived of his royal subsidies and no longer working as a soldier-for-hire, Manucci needed to find a new source of income. Fortunately he soon discovers that he is exceptionally skilled at medicine and declares himself to be a great and wise doctor. This makes perfect sense because, in 17th century India, doctors cannot meaningfully treat the vast majority of their patients. So the most important qualifications for a doctor are a jocular manner and ability to fill conversational gaps, panache and dramatic flair sufficient to awe a patient and their family, and a preternatural instinct that lets them take credit for recoveries and preemptively distance themselves from hopeless cases.34 Here is an example of his medical technique, practiced on his first patient, an Uzbek ambassador:

To induce him to believe that I was a great physician, I asked the patient’s age, and then for a time I assumed a pensive attitude, as if I were seeking for the cause of the illness. Next, as is the fashion with doctors, I said some words making out the attack to be very grave. This was done in order not to lose my reputation and credit if he came to die.

But soon, he gets more ambitious than mere talk therapy. The case that makes his reputation is an old woman who is so sick and weak she barely has a pulse. Manucci builds an improvised enema out of a hookah pipe and a cow’s udder, and violently administers cleansing potions made up of ingredients selected from “certain books” for their geomantic significance. Then he nervously waits. He knows how risky this is, for “a happy cure at the start suffices to give the greatest credit, even if the cure be a mere accident. On the contrary, if there is failure in the first case, even when the doctor is exceedingly learned and experienced [lmao], it suffices to prevent him ever being esteemed.”

Fortunately, the treatment is a total success. Manucci gains a reputation as a doctor capable of “resuscitating the dead.” Soon every Mughal aristocrat is seeking out the services of the great Hakim Niccolao. This almost gets him in trouble, when he is called in to cure a governor who has been poisoned on Aurangzeb’s orders. But he’s able to wriggle out of that one, and keeps his reputation intact despite letting the man die. Soon he is treating everybody from princesses to the destitute. In one case a wealthy and powerful eunuch, who has had his nose and ears removed as a punishment, begs Manucci to cure his disfigurement by cutting the sense organs off a fine-looking slave and causing them to fuse with his own face. Manucci ultimately declines, but not before teasing the slave a bit with a threat to do it.

He may avoid nonconsensual nose transplants, but Manucci does get into some pretty weird stuff. For example: Manucci is a huge fan of bloodletting, which leads the jealous native doctors to start a scurrilous rumor that he is a vampire who drinks the blood of his patients. Just as I was getting outraged on his behalf, however, Manucci mentions that he got really excited upon learning that two morbidly obese men had been condemned to death and petitioned the magistrate to let him harvest human fat from the corpses for use in ointments and potions. This leads a succession of outraged fanatics, both Muslim and Christian, to come try to kill him. He escapes them all, through “God, who seemed to cherish a special desire for my protection.”35 Later, after he’s talked one of them out of killing him, the guy admits to consuming human flesh, but chastises Manucci that you’re supposed to do it discreetly.

And then, we get to the exorcisms. When he is universally recognized as the greatest of all doctors, when his star can rise no further, Manucci decides to convince the population that he is a NECROMANCER who can command demons. “This idea spread because I was a man capable of conversation, in which I showed my nimbleness of wit whenever an occasion presented itself.” It turns out this was also a huge business opportunity, and “they brought before me many women who pretended to be possessed (as is their habit when they want to leave their houses to… meet with their lovers).” Manucci is able to cure the women, eventually, but first he has a bit of fun with them:

The usual treatment was bullying, tricks, emetics, clysters, which caused much amazement, the actual cautery, and evil-smelling fumigation with filthy things. Nor did I desist until the patients were worn out and said that now the devil had fled. In this manner I restored many to their senses, with great increase of reputation, and still greater diversion for myself… I was capable of many practical jokes of this sort. What is certain is that I very seldom lost my temper, and knew how to divert myself in proper time and place with harmless amusements.

In one noteworthy case in Goa, a young man came to Manucci despondent because he is impotent. The man’s wife despises him for his condition and has applied to the archbishop for an annulment. Manucci brushes aside the professional doctors (who have just been transferring him between tubs of cold and hot water in hopes of “effecting a change”), and immediately diagnoses the man with “obstruction of the spleen,” whereupon he prescribes “sustaining and fortifying medicine.” The man is completely cured and proudly returns to demonstrate for the archbishop that he is “fit for marriage.” The archbishop orders him to go and bring his wife back to their house, and while she initially resists him, she is soon thoroughly satisfied. The great doctor Manucci practically glows with satisfaction at having restored domestic harmony to a troubled household, and ends with a grave admonition that a man must examine himself honestly and determine whether he is husband material before getting married.

Speaking of marriage, women keep trying to snag Manucci for one — mostly European women or half-breeds, but in at least one instance an aristocratic Mughal woman who begs him to kidnap her along with all her wealth and bring her back to Italy.36 He resists all such attempts, or goes along with them half-heartedly and then doesn’t fight to save the relationship when it falls apart before the big day. The reason is obvious: he isn’t marriageable and he knows it. Not unmarriageable in the euphemistic sense that his young patient in Goa was, nor riddled with venereal disease as his detractors (he informs us with outrage) whisper. No, the problem is his lifestyle and line of work are not suitable for a family. He knows that his job as a man is to provide stability and security for his little polis, but he equally knows that he has no security of stability to offer, just a life in the shadows and a life on the move.

But just as time weathers even the most inhospitable cliffs into rolling and bucolic hills, so age will sand down a violent and erratic young man into somebody basically normal. As he grew old, Manucci became tired of dealing with the Mughals and their plots, and the next time he was offered a chance at retirement he leapt at it. It so happened that the city of Goa was threatened with conquest by a massive Indian army, and Manucci via his usual wheeling and dealing was able to head off the problem and save the city. For this, he was awarded a knighthood by the Portuguese government,37 which he was then able to parlay into a settled and genteel habitation in Madras. Within a few months he had married a beautiful young widow (a woman born in India to English Catholic parents). As far as we can tell, after that he never went on an adventure again, but not to worry, he tells us: “My residence in Madras will offer no prejudice to the continuation of my History, for, besides the spies I employed, the nobles were pleased to forward me news.”

And he better continue his history! Because he hasn’t yet finished telling us the story of Aurangzeb. He does this over the course of hundreds more pages of warfare and familial strife, which I will not attempt to summarize. The upshot is that Aurangzeb the bloodthirsty and lonely tyrant continues to masterfully outplay everybody else in India, and to increase his power against everybody (even the Europeans!). He kills anybody who so much as looks at him funny; the only troublemakers he doesn’t kill are his own sons and grandsons. Not out of some paternal sentimentality, mind you, but because he wants his line to continue. So instead he locks them up, occasionally tortures them, but always takes care to preserve their physical capacity to procreate. At one point, he has literally every single one of his sons and grandsons in a dungeon somewhere. Manucci can’t help but be impressed: “There can be no doubt that if any king ever had recourse to foresight to prevent disorder, it was Aurangzeb.”

But the sort of order represented by Aurangzeb is terribly fragile. Rather than resolve contradictions, it hides them under a rug, presses pause on them, plunges them into a deep freeze. But they’re there, quietly gathering strength, ready to burst forth with a vengeance when the iron grip relaxes even slightly. Aurangzeb brought the Mughal Empire to its greatest wealth and territorial extent, but within decades of his death it had almost completely unraveled. A bitter and sterile legacy for so great a conqueror. But at the close of Manucci’s history, all of that is still far in the future:

The thing most to be wondered at in my History is the wisdom of Aurangzeb, who, in spite of being an old man of eighty-four years, knows how to regulate affairs with such skill that he maintains himself as king against the will of so many claimants.

And speaking of legacies, did Manucci leave any besides a literary one? Across this whole entire epic, the always talkative, always voluble Manucci only mentions it in one single sentence, so quick that a careless reader can easily miss it: “I had a son, but God chose rather to make him an angel in Paradise than leave him to suffer in this world.” For once I don’t think Manucci is deliberately practicing obfuscation. You can sense the pain in every word of that sentence, and in the unrelated sentences around it. This time his brevity is because he’s barely holding it together. To lose a child is an unimaginable horror, but how much worse it must be when it is the first time in your life that your luck has run out.

Bellomont’s only real success in his mission was to completely poison the well for all future European travelers in Persia. Manucci reports that the next Englishman to visit the court of the Shah was thrown into a dungeon for disloyalty to his liege lord (a story independently corroborated by the French adventurer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier). “[The shah’s] object was to give a lesson to his own nobles as to the manner in which they should serve their king and the fidelity they ought to display, when the occasion arose, in defence of their monarch.”

The book contains extensive discussion of how all elephants and horses that the Mughal princes might want to ride are pre-ridden by an attendant, to “loosen its stomach” and eliminate any flatulence.

This is actually a huge simplification — there are four distinct Venetian codices, all with major differences from each other.

I started with the Forgotten Books paperback, but halfway through the first volume I was hooked, and seeing that I had a thousand pages left to go, picked up a handsome leatherbound set from a used book seller for a song. I would normally never dream of buying a second copy of a book I already own just because it feels nicer in my hands, but you, dear subscribers, have spoiled me.

This is a totally OP and broken build, since as a Venetian he already gets a racial bonus to DEX and CHA.

And you’re one step ahead of Irvine, who as far as I can tell never figured it out.

Probably a bard.

Yep, definitely a bard.

Irvine: “This name and the story connected with the man are quite impossible.”

This may have backfired, since Akbar instead transferred the captured queen to his harem. Irvine thinks the whole story is ridiculous, but Manucci claims to know a grass-mower who discovered one of the cannonballs and a rapacious official who embezzled it.

Irvine lets this one pass without comment, but I can feel his eyeroll from across the centuries.

This one is probably true!

This one is mentioned in the official royal chronicle of that reign.

Manucci does not indicate where they found an interpreter for “the natural language” spoken by our first progenitors.

Or maybe whatever charming aura or glamour he wielded so effectively back then is still working on me, through the pages of this book, four hundred years later.

Irvine was able to find corroborating evidence from a contemporaneous source that this actually happened every year.

You might object that not even Shah Jahan would have time to sleep with two thousand women. That’s not the point! It’s conspicuous consumption, duh. It’s a potlatch. Blatant value destruction as a flex. The point of the first dozen or hundred women in the harem is that you sleep with them, the point of the next hundred is that they aren’t sleeping with anybody at all. You’re so powerful, you’re taking hot, fertile women off the market for no reason except that you can.

The harem sections of these books are subject to the most extreme censorship by Irvine’s Victorian sensibilities, but sometimes something slips past him because he’s just too innocent to get the implication. One example is Manucci’s observation that all visitors to the harem are searched for cucumbers and similarly shaped vegetables.

Dara also loved astrologers. Manucci tells a good story about how one time Dara asked an astrologer about his future, and the sage replied with complete certainty that he would become the next emperor. When Dara asked why he was so confident, the astrologer laughed and said that if Dara did actually become emperor, he would remember the astrologer favorably, and that if he did not, he would be too busy fleeing for his life to punish him. An early example of an apocalypse trade!

I know that whenever I renounce all earthly status, I make sure to name my capital city after myself.

Manipulated, repeatedly used as cannon fodder, drugged, betrayed, wives and children sold into slavery, imprisoned, executed.

Manucci tells a bizarre story about one of these mercenaries, a man named Joao Carvalho, who “had been endowed by Nature with such length of arm that his hands reached below his knees.” This leads some superstitious Hindu villagers to begin worshipping him, because their idols also have exceptionally long arms. He takes up residence in their temple as a living god, requisitioning fine foods, young girls, and miscellaneous treasures whenever he feels like it.

While they may individually be cowards, like all human beings the Mughal troops enjoy beating up on a weaker party. What’s different about the Mughals is that their commanders give them opportunities to commit massacres as a deliberate ploy to improve morale:

Mir Jumlah, who that same day had arrived, counselled Aurangzeb at this juncture to reanimate his men by ordering them to slay and plunder all the Hindus to be found. This was carried out. The slaughter lasted an hour or more, and it put his men into heart, not a soul having resisted them.

There’s a funny moment where some Europeans try to explain naval combat to a Mughal leader. “You see, we bring the cannons onto flimsy wooden boats, and we fire heated shot to set them on fire, and canister rounds that shred each others’ flesh, and we try to ram each others, and once battle is joined there is no way to run away, and we do this on the high seas, and if you fall in the water you will die a horrible death.” The Mughal doesn’t believe them, so they put on a fake example naval battle for him, and he just shakes his head like, “damn, you people are crazy.”

These ranks are documented in excruciating detail in volume 3, which I skimmed.

“Do NOT face Aurangzeb alone when Astral projecting.”

He’ll occasionally just randomly drop sentences like: “I therefore left in the garb of a Carmelite monk.” Manucci can do a convincing impression of anyone, which will come in handy during his medical career.

Or perhaps the answers are in a different book. One of Manucci’s least favorite people is a Frenchman named François Bernier. What a coincidence that Bernier is the other European who wrote a personal memoir about traveling around the Mughal Empire at the exact same time! I am firmly a Manucci partisan and believe him when he says that Bernier made tons of mistakes and doesn’t know what he’s talking about, but I am still tempted to read Bernier’s book on the off-chance that it sheds light on the enigma that was Manucci.

He is very nearly assassinated as a result of this detour, and chalks his survival up to God’s providence. We know that it’s actually because he was a player character (same thing).

He also occasionally tries to proselytize. In one particularly notable instance, a eunuch who has risen to a position of great power is petitioned by an old couple from the countryside. They turn out to be his parents, and aghast at their revealing him to be a country bumpkin, he orders them each to receive a hundred lashes before being thrown out. Manucci tries to intervene by telling him the story of Joseph receiving his treacherous brothers in Egypt, but the cultural gap is too great, and while they are spared the lashes they are still thrown out.

As is traditional, Aurangzeb took a regnal name, which in his case was Alamgir meaning “world conqueror.” This was also the name of his favorite sword (Manucci goes into extensive detail on the names and ornamentation of the various royal swords).

Probably a monk/sorcerer multi-class?

Though Manucci found something to do in one set of hopeless cases:

When I became a physician I baptized in eight years more than fifteen thousand infants, besides those I found on the roadsides moribund, and whom I baptized… But I baptized none except those infants who, as I could clearly see, were bound to die. By this means I have baptized sons of persons in very good positions, princes, and even some of the blood royal. With this profession of doctor it is possible to do some service for God.

A friend of mine who works in a NICU once confessed to me that he did the same.

Conclusive evidence that Manucci is not just a player character, but an awakened one.

He proudly points out to the reader that he could have deceived her and robbed her of all her money if he’d wanted to, but he didn’t.

The letter granting the knighthood (Order of Sao Thiago) is reproduced in its entirety in the book. It lists a number of critical services that Manucci has performed for the crown, many of them at no point mentioned in his narration.

Extremely good review, and sorely tempted to pick this up even though the last thing I need is another 1,000-page memoir to read through.

The fact that it was Venice that produced Manucci, and so many other men like him, seems noteworthy to me. From Athens and Republican Rome to Florence and Amsterdam, people from a polis or polis-like political entity seem to generate a high number of player characters in all kinds of realms. Even early America, it could be argued, matched with this, functioning much like a continent-sized polis up through the Civil War or even up to the New Deal. Certain modes of society and political organization seem to be the best at imbuing individual men with high levels of agency that make them extremely formidable at innovating or solving problems. But this kind of competence can be lost even without losing material prosperity, and once it's lost it is very hard to get back.

Aurangzeb is also the Emperor whose granddaughter is captured/killed by the English pirate Every (another possible player character candidate) in the "greatest single act of piracy in history":

"Later accounts would tell of how Every himself had found "something more pleasing than jewels" aboard, usually reported to be Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb's daughter or granddaughter."

Johnson, Steven (2020). Enemy of All Mankind.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Every

Also, I think you are on your way to a new series: the Compleat D&D character sheets of major historic figures.