GUEST REVIEW: The Triumph of the Moon, by Ronald Hutton

The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, Ronald Hutton (1999; Oxford University Press, 2021).

Your hosts have been occupied with their numerous and belligerent progeny, so please enjoy this guest review from Gabriel Rossman. Gabriel previously collaborated with John on a joint review about nightclubs, and now he is back to tell you about the origins of Wicca.

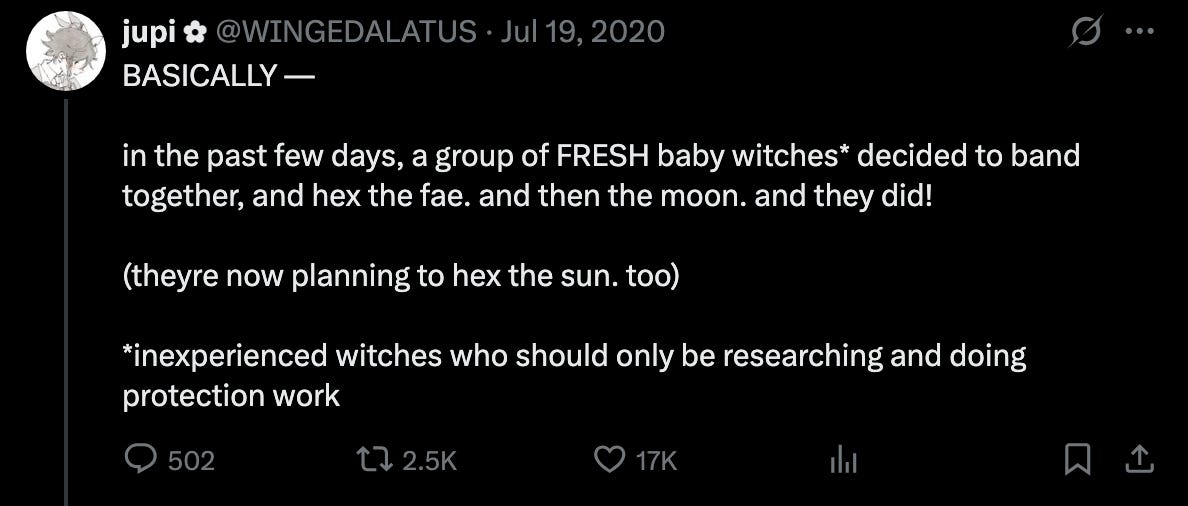

You may recall some disturbing events in 2020, but perhaps the most ominous of all was revealed in a viral Twitter thread that treated with deadly seriousness and a Vox-style explainer the horrifying fact that some witches had been so reckless as to hex the moon.

More mature witches were aghast at the recklessness of these baby witches who cursed the moon (as well as fairies and the sun) willy-nilly and thereby risked severe consequences. It turns out, though, that the idea of witches cursing the moon has an ancient pedigree, dating all the way back to Greco-Roman antiquity and the literary trope of Thessalian witches who could pull the moon out of the heavens and down to earth. These ancient texts were part of the inspiration for Gerald Gardner’s mid-20th century creation of the “drawing down the moon” ritual, but where sources from the classical world implied that a witch could actually pluck the moon from the sky, in Gardner’s version a coven summons the divine personification of the moon to possess a priestess. Moreover, his creation of Wicca also drew extensively from freemasonry, the western ceremonial magic tradition, Crowleyian magic, Gardner’s own ethnographic observations in Southeast Asia — and, most important of all, the theories of James Frazer and Margaret Murray.

One thing that we can be confident that Wicca does not draw upon, however, is a goddess religion that survived the introduction of first the Indo-European *Dyḗus ph₂tḗr in the Bronze Age, and then the Semitic Jesus Christ in late antiquity, before being mostly suppressed in the “burning times” of the early modern era.1 Neo-pagans are not the (great-great-great …) granddaughters of the witches you didn’t burn in the 16th and 17th centuries; rather, they are the granddaughters of upper class romantics whose religious innovations in the early to mid-20th century are best characterized as “creative synthesis.”

Ronald Hutton’s Triumph of the Moon tells the story of the precursors, invention, and development of Wicca. Much of that history can be encapsulated in the mythic genealogy of “Black Annis,” an occasional pagan deity. There was a real medieval anchoress named Agnes Scott who served the church near Leicester and is buried at Swithland Church. She was venerated locally as a Christian saint, but following the Protestant Reformation was reconceptualized as an ogress. Then the 20th century crank archaeologist T.C. Lethbridge interpreted Black Annis as pagan survivalism of the “crone” aspect of the great mother goddess and a corruption of the Celtic goddess Anu. Finally, some modern neo-pagan communities were inspired by Lethbridge’s work to adopt veneration of Black Annis into their liturgy. As Hutton notes, “The gentle and pious Agnes seems therefore to have been turned first into a local saint, then into a local demon, next into a Celtic goddess, and finally into a witch goddess; and all the while her bones have rested in apparent peace at Swithland.”

The changing reputation of Agnes/Annis/Anu reflects a few processes that are common throughout much of the intellectual roots of neo-paganism. You start with the idiosyncratic cruftiness of medieval Catholicism, then Protestants derogate the cult of the saints, feast days, etc. as idolatrous — indeed, practically pagan. Fast forward to 1900, give or take a few decades, and an intellectual with dubious expertise projects pagan survivalism onto historical or ethnographic data. And then finally neo-pagans use the folklorist’s imagined version of the past as inspiration for a “revived” myth and liturgy.

Although Hutton is a historian and does not use the term in the book, Triumph of the Moon is one of the best studies I have ever read of what sociologists of knowledge call performativity.2 In this usage, a scientific theory is performative if the theory did not necessarily describe reality when it was articulated, but has since shaped reality to work in ways predicted by the theory. That is, sometimes a theory can be wrong, but people believe it is true and act on that basis, so a performative theory causes itself to become true — just as Laius and Jocasta probably would have been just fine if they hadn’t gotten around to asking the oracle at Delphi, “So, what’s gonna happen with baby Oedipus?” A slightly weaker version of performativity comes when a theory describes pre-theoretical reality accurately, but in a noisy and approximate way, but then people who are aware of the theory actively conform to its predictions so the random noise goes down and a theory that had been only weakly true becomes strongly predictive. For instance, economics is pretty good at predicting the behavior of students in lab experiments, but it is especially good at predicting the behavior of econ majors, and the hero’s journey described some stories before Joseph Campbell wrote about it in 1949 but many more since his book provided a template (and especially since George Lucas credited the success of Star Wars to following Campbell!).

One of the main applications of performativity in sociology has been to explain the success of economics, a discipline that many sociologists talk about like Jan Brady kvetching “Marcia, Marcia, Marcia.” A nice example is the Black-Scholes-Merton (BSM) equation in financial economics: in theory, BSM described how bond traders already priced options, but in practice traders adopted the equation and used it to guide their estimates of option value. The increase in cognitive tractability this provided allowed Wall Street to dramatically increase the size of the financial derivatives market. (Donald MacKenzie’s book on BSM is called “an engine, not a camera” since BSM powered the options market rather than just documenting it.)3 Similarly, Triumph of the Moon argues that the theory of pagan survivalism does not tell us how religion, folklore, folk medicine, etc. actually worked in Britain prior to the theory’s articulation, but rather that people who were familiar with pagan survivalism theory “revived” paganism along the model posited by the theory.

One of the performative theories is James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, which argued that many myths involve a king or god whose death and rebirth represent winter and spring. Following the popularity of this book, a wave of folklorists rose and began to scan the English countryside for folk customs they could tuck into the Procrustean bed of the dying god archetype. Hutton notes that “unfettered by either history or sociology, the imaginations of folklorists could roam over the material more or less at will,”4 and relates several examples of folklorists imposing farcical readings on the data, such as a 1937 presidential address to the Folk-Lore Society that suggested “pancake-tossing had been a magical rite to make crops grow, that Shrove Tuesday football matches had begun as ritual struggles representing the forces of dark and light, and that Mother’s Day was a relic of the worship of the ancient Corn Mother.”

Perhaps most ridiculous came in 1932, when Violet Alford revived the Marshfield Mummers’ Play, but argued with the locals old enough to remember the play’s previous incarnation because she demanded that the village present the “authentic” version of the play — which is to say the fertility rite that someone steeped in Frazer expected to see. (As of this writing, the Wikipedia article on Marshfield mentions the play and Alford’s role in shaping it, but not the theory-driven nature of her demands and the article straightforwardly describes the play as a “fertility rite.”) Based on such examples, Hutton writes, “by the mid-twentieth century the bossy lady scholar, obsessed with pagan survivals, had become a minor stock character in English fiction.” However, over time, the locals came to accept the theory-driven model. So even if almost nobody in rural England circa 1930 would have told you their customs originated as fertility rites, today a fair number would, which reflects the performative influence of the theory itself.

Hutton notes that by the 1980s, folklorists had come to reject Frazer, but by this point he had entered popular culture. Even if elderly villagers in the 1930s scoffed at the idea that their customs were survivals of pagan fertility rites, by the 1960s and 1970s youth counter-culture embraced folk dancing, crafts, etc., and young rural Boomers often accepted what they learned from early 20th century books and at local folklore clubs about the origins of their practices. (There are other cases of an academic theory having its popular influence grow even as it is discredited within academia: for instance, Hillary Clinton promoted implicit association training as a solution to racial inequality during the 2016 election, a couple years after academic psychologists came to see implicit association tests as one of many casualties of the replication crisis.)

The other major theorist to shape Gardnerian practice was Margaret Murray. Although Hutton reviews Murray’s influences, she stands above them all as the scholar who most thoroughly and influentially articulated the theory now associated with her: not only that substantial aspects of European paganism survived the introduction of Christianity and centuries of inadequate catechism, but that the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries were a major effort to suppress this surviving pagan religion. Her 1921 book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe lays out the model, and Murray includes distinctly Frazerian elements about ritual kings who were sacrificed or self-sacrificed (though now with the added element that these corn kings were allegedly syncretized with the Horned God, an aspect that reflects Pan, as a motif popular with literary figures associated with Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn).

Her terser but equally influential version of the theory was in the entry for “Witchcraft” that she wrote for the Encyclopedia Britannica, which published it from 1929 to 1968.5 For generations, if you heard about Salem and wanted to get more information about witches, you would go to the library and find the Encyclopedia Britannica, (or if you were fancy, the installment plan-financed set on your own bookshelf), reach for the “W” volume, and a few paragraphs in go, “Wow, real witches, amazing!” Murray’s theory has thus been extremely influential. Whenever a Wiccan refers to their religion as “the Old Religion” or a feminist refers to “the Burning Times,” they are alluding to Murray’s theory.

Murray had a big influence on Gardner (and wrote the foreword to his short book Witchcraft Today). Gardner claimed he did not invent Wicca but had been inducted into a coven with centuries of historical continuity, and while this claim was implausible it reflects Murray’s emphasis on an underground witch cult. Among the places Gardner describes this liturgy was his novel, High Magic’s Aid, which he would circulate to potential initiates to gauge their reaction to the rituals described therein.6 “The witch religion portrayed [there],” Hutton writes, “is that of Margaret Murray’s God of the Witches, in virtually every detail, including its dedication to a single male deity of fertility, whose name is given here (again taken from Murray) as Janicot.” The practitioner implementing the ideas of the theorist is classic performativity: there was no pagan witch religion in early modern Europe, but Murray’s claim that there had been was among the most important raw material from which Gardner created an actual pagan witch religion in mid-20th century Britain.

Through all this, there is the question of how so many 20th century scholars got it so wrong — especially given that in the 19th century, both scholars and popular culture understood that witch hunts were moral panics and mass hysteria.7 Black-Scholes-Merton may not have been a perfect description of options prices, but it got much closer to the truth than the idea of pagan survivalism, which is almost completely wrong. Hutton repeatedly notes the importance of relevant expertise, and how often the proponents of pagan survivalism lacked it. Many folklorists influenced by Frazer were simply amateurs, but Murray had legitimate scholarly expertise: she was a respected Egyptologist. This background left her equipped to see a pagan society saturated with magic, but led to a false positive when applying that gaze to Christian medieval and early modern Europe. Nonetheless, in the mid-20th century, Murray’s ideas became accepted in British academia and were integrated into K-12 history textbooks.

However, Hutton notes that such acceptance was mostly from people who did not actively research the witch trials. In contrast, witch trials were an active research area in the United States, and so American scholars remained skeptical even as the Murray thesis became taken for granted in the UK. And while it might be tempting to congratulate America for our pragmatic empiricism, Hutton notes that there was also a subtext of Americans favoring the “persecution of innocents” model for witches because it had become a popular metaphor for the Second Red Scare, as in Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible. American scholars of the 1950s and 1960s may have gotten the history of witch accusations in the 16th and 17th centuries right because they saw it as metaphor for the history of the 1930s through 1950s… which the Venona cables show they got wrong. I rate this 3.41 kiloAlanises.

If performativity is one word starting with a “p” and ending with a “y” that characterizes the themes of Triumph of the Moon, then the other is “polysemy.” This is when the same empirical premise can have different (even wildly different!) meanings for different audiences. In this case, the empirical premise is “at least a thousand years of official Christianity was insufficient to extinguish pre-Christian European paganism, which prominently included a goddess, and so it persisted among rural commoners until the early modern witch hunts and in vestigial form until the Victorian era.” Let us bracket the fact that this empirical premise is wrong and note that people who believed it had wildly different interpretations of its meaning in at least four different respects.

The most basic distinction is whether we ought to sneer at the atavism of pagan survivalism or see it as a laudable tradition worthy of revival. The progenitors of the theory of pagan survivalism, Edward Tylor and James Frazer, were both raised as low church Protestant “dissenters,” people who have traditionally been suspicious that there was something a bit idolatrous or even pagan about the smells and bells of “high church” Christianity.8 Tylor and Frazer both subsequently rejected Christianity, as a matter of private belief if not public practice, in favor of the explicitly rationalistic theologies of deism and atheism respectively. And both saw the civilized and rational as better than the rural and superstitious. Hutton summarizes: “If the general purpose of both Tylor and Frazer was to debunk spirituality and to elevate reason, they also shared a moral disgust for the practices of the ancient and tribal peoples whom they considered. Tylor’s Primitive Culture is littered with expressions such as ‘hideous’, ‘atrocious’, ‘pernicious’, ‘contemptible’, ‘savage’, and ‘barbaric.’” Similarly, Frazer wrote that “the peasant remains a pagan and a savage at heart” whose “ignorance and superstition” would be diminished by urbanization. Depending on the edition, either the explicit text or the 144pt boldface subtext of Frazer’s Golden Bough is that Jesus Christ was just one of many gods to embody the myth and ritual of a king representing the sky, associated with a maiden representing earth, whose sacrificial death and subsequent rebirth promised a good harvest to the kind of living fossil country bumpkins who go in for that sort of thing.

A generation later, we continue to see a rejection of Christianity but also a rejection of rationality with figures like Margaret Murray (who articulated the “early modern witches were actually pagans” thesis and herself cast curses on academic rivals), and Aleister Crowley (who was not only the most influential occultist of the 20th century but also a world-class dirtbag notwithstanding Hutton’s apologetic for him). The notion of not just magic but pagan religion as aspirational came with Gerald Gardner. Gardner was a romantic, in the sense both of exulting nature and being what the kids today call “sex positive,” and he synthesized various occult practice into Wicca to reflect this. Thus, in the roughly 50 years between the peaks of Frazer’s career and Gardner’s, the idea of persistent European paganism went from meaning “I, a rationalist, am better than you Christians, since you are only half a step removed from self-evidently barbaric paganism” to meaning “I, a pagan, am better than you Christians, since you are uptight about sex and don’t appreciate nature.”

This leads to the next issue of different understandings, which is sexuality. Gardner’s conception of Wicca was thoroughly, even primarily, oriented to heterosexuality and sexual complementarity. Gardner followed much of western occultism and semi-scholarly folklore research from the preceding decades in emphasizing a divine pair of a god and a goddess. He embodied this in liturgy, requiring mixed-sex worship with heterosexual initiation. (This mostly meant men initiated women, and vice versa, but could also mean that initiation, especially to the third degree, was via real or symbolic heterosexual intercourse.) Gardner claimed that by ancient tradition, initiation must be either heterosexual or parental, and that the witches who had initiated him told him, “The Templars broke this age-old rule and passed the power from man to man: this led to sin and in so doing it brought about their downfall.”9 Moreover, Gardner’s liturgy developed the “fivefold kiss,” which is gendered to honor the recipient’s penis or uterus as an organ of generation.

The Wicca liturgy seems not just to honor fertility as a theoretical matter but to have more than a little horniness. Several of the “working tools” have BDSM overtones, notably the cord and the scourge, as well as the “athame” (dagger), which was explicitly a phallic symbol, especially when dipped in wine. Likewise, several rites involved nudity.10 Then in the United States in the 1970s, Wicca became an explicitly feminist religion. While current practices demonstrate that feminist Wicca, like many other feminist ideologies and communities, can welcome men so long as relations are egalitarian, the earliest versions of feminist Wicca advocated radical separatist feminism. “Dianic” Wicca was influenced by Gardner, but entirely excluded men and pared the divine couple of horned god and earth maiden down to a henotheistic focus on a single goddess. Hutton describes the 1980 Holy Book of Women’s Mysteries, which argued that “[t]he essence of female spiritual liberation, according to [founder of this school Zsuzsanna] Budapest, was ‘to abide in an all-female energy environment, to read no male writers, to listen to no male voices, to pray to no male gods.’”

Another point of diverging meaning is whether neo-paganism is politically left or right wing. Many of us now think of Wicca as the omnicause protester class assembled at prayer, but this now important strain of Wicca was not seen for the religion’s first few decades. Instead, it was developed in the late 1970s by Starhawk (née Miriam Simos), a California hippy and environmentalist, who took Dianic Wicca, removed the misandry, and developed a highly influential version of Wicca that emphasizes fairies, feminism, and concern for the natural world and all who feel marginalized. The favorite sort of working for Starhawk’s Wicca seems to be things like protesting nuclear weapons. Hutton quotes Starhawk’s Dreaming in the Dark, where she writes that, “Magic had now become ‘the art of evoking power from-within and using it to transform ourselves, our community, our culture, using it to resist the destruction that those who wield power are bringing upon the world.’”

American progressive Wicca has now crossed back over the pond, but Hutton reports that Gardner was likely a conservative, and a writer who studied a British Wicca coven in the 1960s reported its members were all Tories. To get an image of British Wicca prior to American progressive influence, you could do worse than to watch the 1973 film The Wicker Man. In the film, the neo-pagan rural community emphasizes sexuality but is fundamentally conservative. The villagers defer to the local country gentleman, who openly admits he invented their pagan religion based on various influences. (The major deviation from actual Wicca practice is the part where they immolate a priggish but decent cop).11 The immediate precursors to Wicca in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn tended to also be on the right: Hutton describes Aleister Crowley as a high Tory, Dion Fortune as having similar sympathies, and W.B. Yeats as dabbling in fascism. He doesn’t discuss it in the book, but there is also now a resurgent far-right neo-paganism, variously called Wotansvolk, Asatrú, or Odinist and associated with white supremacist prison gangs. (As implied by the names, they practice reconstructed Norse religion rather than a syncretic/comparative reconstruction like Wicca.)

As you might guess from some of the more extreme variation in the political meaning of pagan survivalism and neo-paganism, another split is over attitudes towards Jews. Almost by definition, neo-paganism means rejecting ethical monotheism, which originated with Judaism, but there’s one group of neo-pagans that took it a lot further… As Hutton describes in The Witch, the Nazis were big fans of the Murray thesis that the early modern witch hunts suppressed pagan survivalism — or, as they conceived of it, the invasive oriental/Semitic religion of Christianity never completely took root until the early modern witch hunts suppressed the pagan aspect of the Germanic folk spirit. Himmler tasked SS officer Rudolf Levin with collecting the Hexenkartothek (“witch card index”) which attempted to catalog every witch execution and thereby prove that the early modern witch hunt was a sustained Semitic attack on Aryan women.12

Contrast this to the late 20th century, where you have the thoroughly progressive Starhawk conceptualizing the witch hunts not as Germanic vs. Semitic, or even pagan vs. monotheist, but as oppressed vs. oppressor — and since Jews were historically oppressed, this implies a philosemitic moral to the Burning Times myth. Hutton writes: “By Truth or Dare, Starhawk was explicitly equating the social experiences of Jews and witches, and whereas other Pagan writers had excoriated the whole Judaeo–Christian tradition as the source of the earth’s problems, she was now inclined to regard criticism of Judaism as anti-Semitism while retaining the animosity towards Christian Churches. She held Jewry up for admiration as an example of the capacity of the dispossessed to survive because of spiritual bonds, and her view of politics as a struggle carried on by small groups of right-thinking people amid hostile and ignorant masses drew at least partly upon this example.”

The polysemy of the alleged fact that European paganism survived the introduction of Christianity boils down to: whom do you see as your enemy in the present? If you resent Christianity as irrational theism, you’ll join Frazer in mocking Christianity as rhyming with pagan fertility rites. If you’re opposed to pre-sexual revolution prudery and soot-choked industrial towns, you embrace Gardner’s liturgy and mythology of heterosexually horny nature worship. If you hate men, you’ll practice Dianic Wicca, but if you hate The Man you’ll practice Starhawk’s variety. And if you see Christianity as a Semitic threat to der deutschen Volksgeist, you spend nine years collecting die Hexenkartothek.

The one aspect of this myth that might be true is a pre-Indo-European goddess religion. The idea that Stone Age female figurines like the Venus of Willendorf represent a goddess religion is plausible but unprovable, given that the figures predate writing by about 26,000 years and so we have no literary evidence to contextualize the archaeology. But even saying that the Neolithic goddess cult was possible but not settled fact, as archaeologist Peter Ucko did in the 1960s, was enough to upset Murray, who “sent Ucko a furious letter, informing him that he had no right to speak about the goddess, because he was, first, far too young, and, second, a man.” While there might have been widespread neolithic European goddess worship, all other aspects of the “Murray thesis” — the idea that witches executed circa the Protestant Reformation were practicing a pre-Christian goddess religion — are demonstrably false. Hutton notes the falsity of the Murray thesis incidentally in Triumph of the Moon and argues against it at length in his later book, The Witch.

“Performativity” has many other uses and meanings, all ultimately stemming from the analytic philosophy concept of speech acts. Perhaps most famously, in recent years the term has had applications in gender and queer theory, but I won’t be addressing that meaning here as I don’t feel like giving myself an ulcer by taking enough ibuprofen to make my way through Butler.

Kieran Healy has noted that it is not just economists whose theories shape reality but also sociologists ourselves, with sociological theory about social networks providing many of the assumptions behind Web 2.0. For instance, sociologists have long posited a network heuristic called transitivity (aka triadic closure), which is to say that if you and I have mutual friends then we are more likely to become friends with each other than would be two otherwise similar people chosen at random. Social media platforms use this model as the basis for their “you may also know” recommendation engines, which means that transitivity is probably a good deal stronger in a world shaped by social media than it was in 1994, when Stanley Wasserman and Katherine Faust described transitivity in their influential textbook.

In a subsequent book, Hutton assesses the accuracy of various claims of pagan survivalism. He shows that a few cultural tropes or practices, notably fairies, have authentic pagan roots but in general “it was invented in the 19th century” is a much safer bet than “it dates back to paganism.”

Fortunately cranks writing the encyclopedia is an issue safely in the past.

“Check out my fantasy novel (that describes the counter-cultural religion with transgressive rites that I actually practice and wish to induct you into)” is a more elaborate version of using plausibly deniable indirect speech to broach a taboo proposition.

Volume 2 of Charles Mackay’s 1841 Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds contains a lengthy section on the early modern witch hunts that captures the 21st century scholarly consensus that witch hunts were the result of a moral panic and opportunistic expression of grudges as abetted by poor legal process. Mackay’s history differs from the current scholarly consensus only in failing to understand that witch trials were most aggressive in weak states, especially those whose establishment of religion was sufficiently tenuous as to be threatened by popular sentiment that the prince exercised insufficient brutality in defending the populace against hostis humanis generis.

It is interesting that Sir Edward and Sir James were both knighted, but so has been Sir Ronald since publication of Triumph of the Moon, and a major the point of the book is the latter thinks the former were full of it.

Gardner seems to be alluding to, and assessing as credible, the charges and evidence against the Templars that were extracted under torture when Philip IV sought to escape his debts through the traditional royal life-hack of persecuting his creditors, but Gardner found merit in the Templar’s alleged idolatry and witchcraft and shame only in the charge of sodomy. Gardner’s opposition to male homosexuality contrasts to his precursors in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Notably, Victor Neuburg wrote “The Triumph of Pan,” a poem so intensely homoerotic it makes even the reader not usually inclined towards either homosexuality or masochism give a contemplative nod to the possibility of being severely buggered by a satyr. Aleister Crowley, the bisexual top whom Neuburg divinized in his poem, later wrote the “Hymn to Pan,” which is also homoerotic, but not as graphically so as its less famous predecessor composed from the bottom’s point of view.

All the stuff from Gardner about nudity, fivefold kiss, sexual initiation rites, binding, and flogging sounds like “my ‘I invented a religion to indulge my sexual appetites’ t-shirt is raising a lot of questions already answered by my ‘I invented a religion to indulge my sexual appetites’ t-shirt.” Hutton does his best to exculpate Gardner, but this effort comes across like a talented lawyer doing legal aid work who has reviewed the scant evidence provided by his obviously-guilty defendant, asks “is there anything else that might help your case?” and upon being told that’s it, puts on a brave face and says, “OK, we’ll see if the jury buys it.” Hutton argues that flogging was humanely applied and a way to achieve a trance state without exciting Gardner’s asthma, binding with cords was to achieve dizziness, and also we can tell it wasn’t erotic because Gardner’s surviving porn collection was vanilla pin-ups. Likewise, Hutton says Gardner was never subsequently MeToo’d and thus wasn’t a case of the familiar pattern of the leader of a new religious movement using that position for sexual predation. Uh huh.

Wicca does not practice human sacrifice, but some of its precursors and influences had a theoretical interest in the subject. Frazer of course gave great emphasis to the sacrifice of the king of the sacred rites and this theme is echoed in Wicker Man. Robert Graves (yes, the I, Claudius guy) had serious mommy issues, one expression of which was a masochistic fantasy about young men being tortured and sacrificed by priestesses. Aleister Crowley infamously claimed to have sacrificed an average of 150 of his own male children a year, but this logistically improbable claim seems to have been an erudite joke about non-procreative ejaculations.

Imagine the balls it took to be on the thesis committee in 1944 at University of Munich that rejected Untersturmführer Levin’s habilitation (second dissertation).

![[Gerald Brosseau Gardner] [Gerald Brosseau Gardner]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!a-A8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0454281f-ce31-4ccc-bd83-9543bbf1a9ff_200x300.jpeg)

I recently listened to an interesting podcast with J.J. Storm which situated /The Golden Bough/ in its historical context. ( https://shwep.net/oddcast/jason-ananda-josephson-storm-on-james-george-frazer-the-golden-bough-and-western-esotericism/ ) One thing I wanted to highlight to add to this excellent review is that Frazer was not some lone wolf stochastic terrorist rising up against Christianity. The idea of "pagan survivals" was deeply exciting to hundreds of 19th century European intellectuals who are completely forgotten today; you can read a long list of them in Joscelyn Godwin's /The Theosophical Enlightenment/. Frazer was actually behind his times theoretically, and most folklorists and anthropologists were already discarding his thesis by the 1930s. What made him unique, though, was his impressive industry. He was not afraid to sit in the British Library and slowly translate old articles from Dutch or Spanish language journals just to find a citation or two to stick into the third edition of his work. Even today, some anthropologists find /The Golden Bough/ useful simply because of its massive number of citations in a diverse number of languages. It's like an encyclopedia written entirely to prove a point. It's unsurprising that the creators of Wicca looked to Frazer instead of the hundreds who came before him, most of whom were just playing wishful thinking with a handful of texts.

Another amusing point raised by the podcast is that well before the creation of Wicca, both Frazer and Margaret Murray were cited by Lovecraft when he first described the Cthulhu cult.

An amusing sidelight on Margaret Murray's moonshine is that a number of British Golden Age mystery writers wrote mysteries in the 1930s in which folk cult survivals, or ostensible ones, were at play--usually (a bit like in The Wicker Man) created by a charismatic local, often as a cover for nefarious but entirely non-supernatural doings. One of my favorite blogs has an entertaining post about one of these: https://thepassingtramp.blogspot.com/2017/05/it-takes-village-case-of-unfortunate.html

Also interesting, for anyone interested in the reception of Murray's moonshine, is this article: Jacqueline Simpson (1994) Margaret Murray: Who Believed Her, and Why?, Folklore, 105:1-2, 89-96, DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.1994.9715877 The first paragraph is worth sharing, I think:

No British folklorist can remember Dr Margaret Murray without embarrassment and a sense of paradox. She is one of the few folklorists whose name became widely known to the public, but among scholars her reputation is deservedly low; her theory that witches were members of a huge secret society preserving a prehistoric fertility cult through the centuries is now seen to be based on deeply flawed methods and illogical arguments. The fact that, in her old age and after three increasingly eccentric books, she was made President of the Folklore Society, must certainly have harmed the reputation of the Society and possibly the status of folkloristics in this country; it helps to explain the mistrust some historians still feel towards our discipline. It is disturbing to see one speaking of "the folklorist or Murrayite" interpretation of witchcraft, as if the two words were synonymous, and all folklorists espoused her views (Russell 1980,41)—whereas, as I hope to show, she wrote only one substantial article on witches for Folklore (in 1917), the reviews of her books that appeared there were far from enthusiastic, and as far as can now be seen the only member of the Folklore Society to adopt her theory wholeheartedly was the very untypical Gerald Gardner, founder of the Wicca movement.