JOINT REVIEW: The Ancient City, by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges

The Ancient City: A Study of the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and Rome, Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1864; trans. Willard Small, Pantianos Classics, 2017).

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

John: A few months ago I tried moving the Iliad from the list of books I'm good at pretending to have read to the list of books I've actually read, and to my surprise I bounced off of it pretty hard. What I wasn't expecting was how much of it is just endlessly tallied lists of gruesome slayings, disses, shoutouts to supporters, more killings, women taken by force, boasts about wealth, boasts about blinged-out-equipment, more shoutouts to the homies from Achaea who here repreSENTing, etc. The Iliad is basically one giant gangster rap track, and gangster rap is kinda boring.

What was cool though is I felt like I came away with a much better understanding of Socrates, Plato, and that whole milieu. Much like it's easy to miss the radicalism of Christianity when you come from a culture steeped in it, it's easy to miss the radicalism of Socrates if you don't understand that this is the culture he was reacting against. Granted, the compilation of the Homeric epics took place centuries before the time of classical Athens, but my sense is that in important respects things hadn't changed all that much. In our society, even people who aren't professing Christians have been subliminally shaped by a vast set of Christian-inflected moral and epistemic and metaphysical assumptions. Well in the same way, in the Athens of Socrates and of the Academy, the “cultural dark matter” was the world of the Iliad: honor, glory, blinged out bronze armor, tearing hot teenagers from the arms of their lamenting parents, etc.

We have a tendency to think of the Greek philosophers as emblematic of their civilization, when in reality they were one of the most bizarre and unrepresentative things that happened in that society. But Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges is here to tell us it wasn't just the philosophers! So much of our mental picture of Ancient Greece and Rome is actually a snapshot of one fleeting moment in the histories of those places, arguably a very unrepresentative moment at which everything was in the process of collapsing. It's like if [POP CULTURE ANALOGY I'M TOO TIRED TO THINK OF]. And actually once you think about it this way, everything makes way more sense. All those weird customs the Greeks and Romans had, all the lares and penates and herms and stuff, those are what these societies were about for hundreds and hundreds of years, and the popular image is just this weird encrustation, this final flowering at the end.

As the official classicist of the Psmith household, was this all already incredibly obvious to you?

Jane: Well, yes. Because the thing is, as weird and crufty and full of archaism as it is, the Iliad is actually the first step in the rationalization of the ancient world. Like, it's even weirder before.

Homer (“Homer”) presents the gods as having unified identities, desires, and attributes, which of course you have to have in order to have any kind of coherent story but which is not at all the way the Greeks understood their gods before him (or even mostly after). The Greeks didn't have a priestly caste with hereditary knowledge, or Vedas, or anything like that, so their religion is even more chaotic than most primitive religions. “The god” is a combination of the local cult with its rituals, the name, the myths, and the cultic image, and these could (and often did) spread separately from one another. The goddess with attributes reminiscent of the ancient Near Eastern “Potnia Theron” figure is Hera, Artemis, Aphrodite, Demeter, or Athena, depending on where you are. Aphrodite is born from the severed testicles of Ouranos but is also the daughter of Zeus and Dione. “Zeus” is the god worshipped with human sacrifice on an ash altar at Mt. Lykaion but also the god of the Bouphonia but also a chthonic snake deity. Eventually these all get linked together, much later, primarily by Homer and Hesiod, but even after the stories are codified — okay, this is the king of the gods, he's got these kids and this shrewish wife, he's mostly a weather deity — the ritual substrate remains. We still murder the ox and then try the axe for the crime, which has absolutely nothing to do with celestial kingship but it's what you do. If you're Athenian. Somewhere else they do something completely different.

I also really enjoyed this book, and I think for similar reasons to you. Because you're right, at the end of the classical world it wasn't just the philosophers. One major theme in Athenian drama is the conscious attempt to impose rationality/democracy/citizenship/freedom (all tied together in the Greek imagination) in place of the bloody, chthonic, archaic world of heredity.1 It's an attempt at a transition, and one which gets a lot of attention I think in part because people read the Enlightenment back into it. But my favorite part of the The Ancient City is Fustel de Coulanges's exploration of the other end of the process: where did all the weird inherited ritual came from in the first place?!

The short version of the answer is “the heroön.” Or as he puts it: “According to the oldest belief of the Italians and Greeks, the soul did not go into a foreign world to pass its second existence; it remained near men, and continued to live underground.” Everything else follows from here: the tomb is required to confine the dead man, the burial rituals are to please him and bind him to the place, the grave goods and regular libations are for his use, and he is the object of prayers. Fustel de Coulanges is incredibly well-read (that one sentence I quoted above cites Cicero's Tusculan Disputations, “sub terra censebant reliquam vitam agi mortuorum,” plus Euripides' Alcestis and Hecuba), and he references plenty of Vedic and later Hindu texts and practices too. I also immediately thought of the Rus' funeral described by ibn Fadlan and retold in every single book about the Vikings, in which, after all the exciting sex and human sacrifice is over, the dead man's nearest kinsman circles the funerary ship naked with his face carefully averted from it and his free hand covering his anus. This seems like precautions: there's something in the ship-pyre that might be able, until the rites are completed, to get out.2 And obviously we now recognize tombs and burial as being very important to the common ancestors of the classical and Vedic worlds — from Marija Gimbutas's kurgan hypothesis to the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans with the Yamnaya culture (Ямная = pit, as in pit-grave) — their funerary practices have always been core to how we understand them. But I’m really curious how any of this would have worked, practically, for pastoral nomads! Fustel de Coulanges makes it sound like you have your ancestor’s tomb in your back yard, more or less, which obviously isn't entirely accurate when you’re rolling around the steppe in your wagon.

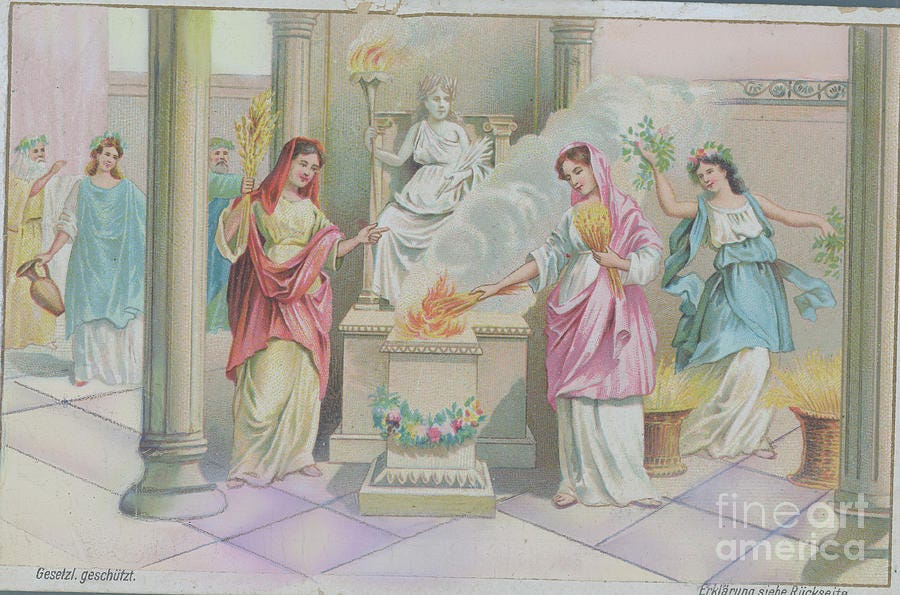

I'd also be interested to see an archeological perspective on his next section, about the sacred hearth. This is the precursor of Vesta/Hestia and also Vedic Agni, the reconstructed *H₁n̥gʷnis (fire as animating entity and active force) as opposed to *péh₂ur (fire as naturally occurring substance). I looked back through my copy of The Wheel, the Horse, and Language and (aside from a passing suggestion that the hearth-spirit’s genderswap might be due to the western Yamnaya‘s generally having more female-inclusive ritual practices, possibly from the influence of the neighboring Tripolye culture), I didn’t find anything. I suppose this makes sense — you can't really differentiate between the material remains of a ritual hearth and a “we're cold and hungry” hearth, especially if people are also cooking on the ritual hearth so there's not a clear division anyway. But if anyone has done it I'd like to see.

I don't know enough of the historiography to know whether Fustel de Coulanges was saying something novel or contentious in the mid-19th century, but he seems to be basically in line with more recent scholarship even if he's not trendy. But The Ancient City can be read as a work of political philosophy as well as ancient history! So what did you make of his description of the development of the family and then the city as its outgrowth? Did it ring true or illuminate anything?

John: The claim that the fundamental religion of the Greco-Roman world was ancestor veneration, and that everything else was incidental to or derivative from that, is so interesting. I'm not conversant enough with the ancient sources to know whether Fustel de Coulanges is overstating this part, but if you imagine that he's correct, a lot of other things click into place. For instance, he does a good job showing why it leads pretty quickly to extreme patrilineality, much as it did in the one society that arguably placed even more of an emphasis on ancestor veneration — Ancient China.

And like in China, what develops out of this is an entire domestic religion, or rather a million distinct domestic religions, each with its own secret rites. In China there were numerous attempts over the millennia to standardize a notion of “correct ritual,” none of which really succeeded, until the one-two punch of communism and capitalism swept away that entire cultural universe. But for thousands of years, every family (defined as a male lineage) maintained its own doctrine, its own historical records, its own gods and hymns and holy sites. It's this fact that makes marriage so momentous. The book has a wonderfully romantic passage about this:

Two families live side by side; but they have different gods. In one, a young daughter takes a part, from her infancy, in the religion of her father; she invokes his sacred fire; every day she offers it libations. She surrounds it with flowers and garlands on festal days. She asks its protection, and returns thanks for its favors. This paternal fire is her god. Let a young man of the neighboring family ask her in marriage, and something more is at stake than to pass from one house to the other.

She must abandon the paternal fire, and henceforth invoke that of the husband. She must abandon her religion, practice other rites, and pronounce other prayers. She must give up the god of her infancy, and put herself under the protection of a god whom she knows not. Let her not hope to remain faithful to the one while honoring the other; for in this religion it is an immutable principle that the same person cannot invoke two sacred fires or two series of ancestors. “From the hour of marriage,” says one of the ancients, “the wife has no longer anything in common with the religion of her fathers; she sacrifices at the hearth of her husband.”

Marriage is, therefore, a grave step for the young girl, and not less grave for the husband; for this religion requires that one shall have been born near the sacred fire, in order to have the right to sacrifice to it. And yet he is now about to bring a stranger to this hearth; with her he will perform the mysterious ceremonies of his worship; he will reveal the rites and formulas which are the patrimony of his family. There is nothing more precious than this heritage; these gods, these rites, these hymns which he has received from his fathers, are what protect him in this life, and promise him riches, happiness, and virtue. And yet, instead of keeping to himself this tutelary power, as the savage keeps his idol or his amulet, he is going to admit a woman to share it with him.

Naturally this reminded me of the Serbs. Whereas most practitioners of traditional Christianity have individual patron saints, Serbs de-emphasize this and instead have shared patrons for their entire “clan” (defined as a male lineage). Instead of the name day celebrations common across Eastern Europe, they instead have an annual slava, a religious feast commemorating the family patron, shared by the entire male lineage. Only men may perform the ritual of the slava, unmarried women share in the slava of their father. Upon marriage, a woman loses the heavenly patronage of her father's clan, and adopts that of her husband, and henceforward participates in their rituals instead. It's... eerily similar to the story Fustel de Coulanges tells. Can this really be a coincidence, or have the Serbs managed to hold onto an ancient proto-Indo-European practice?3 I tend towards the latter explanation, since that would be the most Serbian thing ever.

But I'm more interested in what all this means for us today, because with the exception of maybe a few aristocratic families, this highly self-conscious effort to build familial culture and maintain familial distinctiveness is almost totally absent in the Western world. But it's not that hard! I said before that the patrilineal domestic worship of ancient China was annihilated in the 20th century, but perhaps that isn't quite as true as it might at first appear. I know plenty of Chinese people with the ability to return to their ancestral village and consult a book that records the names and deeds of their male-lineage ancestors going back thousands of years. These aren't aristocrats,4 these are normal people, because this is just what normal people do. And I also know Chinese people named according to generation poems written centuries ago, which is a level of connection with and submission to the authority of one's ancestors that seems completely at odds with the otherwise quite deracinated and atomized nature of contemporary Chinese society.

Perhaps this is why I have an instinctive negative reaction when I encounter married couples who don't share a name. I don't much care whether it's the wife who takes the husband's name or the husband who takes the wife's, or even both of them switching to something they just made up (yeah, I'm a lib).5 But it just seems obvious to me on a pre-rational level that a husband and a wife are a team of secret agents, a conspiracy of two against the world, the cofounders of a tiny nation, the leaders of an insurrection. Members of secret societies need codenames and special handshakes and passwords and stuff, keeping separate names feels like the opposite — a timorous refusal to go all-in.

And yet, literally the entire architecture of modern culture and society6 is designed to brainwash us into valuing our individual “autonomy” too much to discover the joy that comes from pushing all your chips into the pot. Is there any hope of being able to swim upstream on this one? What tricks can we steal from weak-chinned Habsburgs and the Chinese urban bourgeoisie?

Jane: I have a friend whose great-grandmother was one of four sisters, and to this day their descendants (five generations’ worth by now!) get together every year for a reunion with scavenger hunts and other competitions color-coded by which branch they’re from. Ever since I heard this story, one of my goals as a mother has been to make the kind of family where my grandchildren’s grandchildren will actually know each other, so I’ve thought a lot about how to do that.

On an individual level, you can get pretty far just by caring. People — children especially, but people more generally — long to know who they are and where they came from. In a world where they don’t get much of that, it doesn’t take many stories about family history and trips “home” to inculcate a sense a “fromness”: some place, some people.7 Our kids have this, I think, and it’s almost entirely a function of (1) their one great-grandparent who really cared and (2) the ancestral village of that branch of the family, which they’ve grown up visiting every year. Nothing builds familial distinctiveness like praying at the graves of your ancestors! But that doesn’t scale, because we’re a Nation of Immigrants(TM) and we mostly don’t have ancestral villages. (The closest I get is Brooklyn, a borough I have never even visited.) And even for the fraction of Americans whose ancestors were here before 1790 (or 1850, or whatever point you choose as the moment just before urbanization and technological innovation began to really dislocate us), the connection to people and place grows yearly more strained.

For the highly mobile professional-managerial class, moving for that new job, it’s even worse. You and I live where we live not because we like it particularly, or because we have roots here, but because it’s what made sense for work. And though we sometimes idly talk about moving somewhere with better weather and more landscape (not even a prettier landscape, just, you know, more), I don’t think any of the places we’d consider have a sufficiently diverse economic base that I’d bet on them being able to support four households worth of our children and grandchildren. We often think of living in your hometown in order to stay connected to your family as a sacrifice that children make — hanging out a shingle in the third largest town in Nebraska rather than heading to New York for Biglaw or something like that — but I increasingly see giving your children a hometown they can reasonably stay in as a sacrifice that we can make as parents.

Fustel de Coulanges has this beautiful, poetic passage about the relationship between the individual and the family:

To form an idea of inheritance among the ancients, we must not figure to ourselves a fortune which passes from the hands of one to those of another. The fortune is immovable, like the hearth, and the tomb to which it is attached. It is the man who passes away. It is the man who, as the family unrolls its generations, arrives at his house appointed to continue the worship, and to take care of the domain.

I love this as a metaphor. It’s generational thinking on steroids: it’s not just “plant trees for your grandchildren to enjoy,” it’s “don’t sell the timberland to pay your bills because it’s your grandchildren’s patrimony.” And there’s something to it, especially when the woods are inherited, because it’s your duty to pass along what was passed down to you. You should be bound by the past, you should be part of something greater than yourself, because the “authentic you” is an incoherent half-formed ball of mutually contradictory desires and lizard-brain instinct. It’s the job of your family and your culture (but I repeat myself) to mold “you” into something real, like the medieval bestiaries though mother bears did to their cubs. But take it literally, as Fustel de Coulanges insists the ancients did, and it feels too much like playing Crusader Kings for me to be entirely comfortable. Yeah, this time my player heir is lazy and gluttonous, but his son looks like he’s shaping up okay, maybe we’ll go after Mecklenburg in thirty years or so. The actual individual is basically incidental to the process. And the entire ancient city is built of this!

The book describes how several families (and it’s worth noting that this includes their slaves and clients; the family here is the gens, which only aristocrats have) come together to form a φρᾱτρῐ́ᾱ or curia, modeled exactly after the family worship with a heroic ancestor, sacred hearth, and cult festivals. Then later several phratries form a tribe, again with a god and rites and patterns of initiation, and then the tribes found a city, each nested intact within the next level up, so that the city isn’t just a conglomeration of people living in the same place, it’s a cult of initiates who are called citizens. And, as in the family, the individual is really only notable as the part of this vast diachronic entity that’s currently capable of walking around and performing the rites. The ancient citizen is the complete opposite of the autonomous, actualized agent our society valorizes, which makes it a useful corrective to our excesses. That image of the family unrolling, of the living man as the one tiny part that’s presently above ground, is something we deracinated moderns would do well to guard in our hearts. But that doesn’t make it true.

Almost by accident, in showing us what inheritance and family meant for the ancient world, Fustel de Coulanges illustrates why Christianity is such a revolutionary doctrine. For the ancients, the son and heir is the one who will next hold the priesthood in the cult of his sacred ancestor. In Christ, we are each adopted into sonship, each made the heir of the Creator of all things, “no more a servant, but a son; and if a son, then an heir of God through Christ.”

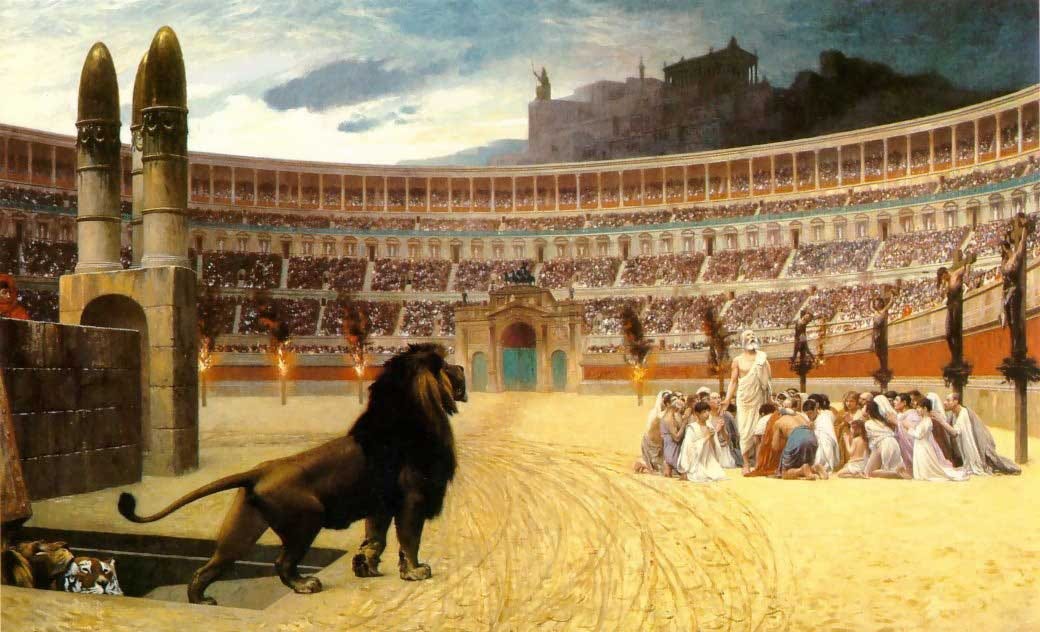

John: I think it's a little bit more prosaic than that. Reading this book really makes it clear how nearly every aspect of Christianity was like a laser-guided bomb aimed at one or more of the pillars holding up the social order of ancient Mediterranean civilization.

Consider celibacy: Fustel de Coulanges examines several ancient legal codes and finds that in all of them the deliberate refusal to procreate was a crime that carried severe punishments. This makes total sense in light of all you've said — a man does not belong to himself, he belongs to his family, a diachronic (or transtemporal?) entity that lives in and through and above individuals. Deliberate celibacy would be like your hand or your kidney refusing to perform its assigned function and trying to murder you instead. Cancer, in other words. And the solution to cancer is to cut it out and destroy it.

Now imagine a religion praising cancer and vaunting the tumor as the highest form of biological life, and maybe we can feel a sliver of the horror that the ancients must have felt towards Christianity. And it wasn't just celibacy either — in area after area Christianity emancipated individuals from the dense, ancient web of obligations, loyalties, and client-patron relationships. Loyalty to the city and loyalty to the family were both such incomparably important qualities for the ancients that Sophocles got several tragedies out of the collisions when they came into conflict, but Christianity in its most radical form says that both are ephemeral and contingent, and must be subordinated to a higher loyalty — fidelity to the Truth. To the ancients I bet this didn't just seem like antisocial behavior, I bet it seemed like the apocalypse. No wonder there were so many martyrs. No wonder so many of them were martyred by their closest relations.

I'm almost tempted to say that that old snake Gibbon was right, it was Christianity that destroyed the Roman Empire, destroyed the entire ancient Mediterranean civilization that had lasted for a millennium or more, first bit-by-bit then all at once. But of course that isn't quite right either. By the time Pentecost occurred, the dissolution was already well underway. Christianity massively accelerated a process that was inexorable by then, and changed the shape of what was to come after it, but the collapse was baked in.

Read any of the Roman authors from either shortly before or shortly after the Lord's birth — Virgil, Cicero, Pliny, Suetonius — all of them, in one way or another, are obsessed with the unraveling of the matrix of tribal and familial relationships that Fustel de Coulanges describes. There were a lot of reasons for it, including but not limited to: mass migration to the cities, economic rationalization that replaced freehold farming with massive latifundia (plantations), and just the accumulated stresses from centuries of continuous warfare and expansion. The cumulative effect of all this was that a society formerly governed by ritual, familial and civic piety, tribe, and clan was transformed into an ocean of atomized and deracinated individuals engaging in mass politics.8

One of my favorite passages in Gibbon's Decline and Fall9 is in the intro to the chapter on Alaric's invasion of Italy. Gibbon contrasts this with Hannibal's invasion 700 years earlier, and goes on this beautiful riff about how on paper, the Rome of the 5th century AD looks incomparably stronger than that of the 3rd century BC — it had a massively larger population, greater wealth, a greater technological edge over its opponents, etc. And yet when it came to a responsibility as basic as that of defense against a foreign invasion, all the GDP and technology in the world wasn't able to make up for a lack of asabiyyah. When Hannibal annihilated the legions at the Battle of Cannae, something like 20% of the entire adult male population of Rome was killed, including most of her military and political leadership, to which the Romans simply gritted their teeth and raised a few more armies. The descendants of those heroes, despite having a vastly larger population to draw from, weren't able to muster a single legion or a single capable commander, and surrendered their city to the Visigoths almost without a fight.

Rome was a rocket that soared into the sky and then came crashing back down, and it's easiest to see it right at the apogee, the point midway between the first and the last great invasions of Italy. The first century glory days of Rome, the time that we moderns consider the height of her power, were actually a moment of deep institutional and social decay. Like an exothermic reaction — a bonfire or an explosion or a fireworks display — what we notice immediately is the ebullient, magnificent blaze. But it's easier to miss all the fuel that's being consumed: solidarity, economic resilience, social technology, all of it woven through with the tight bands of ancient law and custom that Fustel de Coulanges documents. Just as the Greek philosophy we love was an uncharacteristic flash in the pan, an evanescent moment that subverted and destroyed the culture that had given rise to it; so too the Roman imperial achievement was an engine fueled by a society and a citizen-soldiery that it quickly burned to cinders.

I wonder if every civilizational golden age would turn out to have this unsustainable character if you inspected it closely. If so it would explain a historical mystery, which is why these epochs are rare, and why they never last long. From this angle history looks a bit like a 2-stage cyclic phenomenon wherein the long “dark ages” are actually epochs of patient stewardship of economic, cultural, and demographic resources, whilst the short “golden ages” are a kind of manic civilizational fire sale of the accumulated inheritance. Maybe we need a new historiography founded on the idea that what we have heretofore considered dark ages are the true golden ages, and vice versa. This transvaluation of values would be like a temporal version of James Scott's attempted reversal of civilization and barbarism.

Alas, while peasants could vote with their feet and migrate across the imperial frontier, our options for time travel are a bit more limited. Would we prefer to live in the cozy but constricting deep prehistory of a civilization, or in the wild glory of its last days? No doubt it would depend a lot on who we imagine being in each of these phases, but at the end of the day it doesn't matter, because we don't have a choice. May as well sit back and enjoy watching the blaze. It will be beautiful and exhilarating while it lasts.

And of course that tension is extra intriguing because the dramas are always performed at one of these inherited rituals, in this case the city-wide Great Dionysia festival, although it was a relatively late addition to the ritual calendar. Incidentally it's way less bizarre than the Attic “rustic” Dionysia which is all goat sacrifices and phallus processions. (There's also the Agrionia in Boeotia which is about dissolution and inversion and nighttime madness, and another example of "the god" being a rather fluid concept.)

Neil Price, in his excellent Children of Ash and Elm, says that the archeological evidence seems to confirm this:

Most of the objects [in the Oseberg ship burial] were deposited with great care and attention, but at the very end most of the larger wooden items — the wagons, sleds, and so on — were literally thrown onto the foredeck, beautiful things just heaved over the side from ground level and being damaged in the process. The accessible end of the burial chamber was then sealed shut by hammering planks across the open gable, but using any old piece of wood that seems to have been at hand. The planks were just laid across at random — anything to fill the opening into the chamber where the dead lay. The nails were hammered in so fast one can see where the workers missed, denting the wood and bending or breaking off the nail heads.

Speaking of ancient proto-Indo-European practices, his descriptions of the earliest Greek and Roman marriage ceremonies are also fascinating. They incorporate a stylized version of something very reminiscent of Central Asian bride kidnapping! I like to think this is also a holdover of some unfathomably old custom, rather than convergent evolution.

IMO China never really regained a true aristocracy after Mongol rule and the upheavals preceding the establishment of the Ming dynasty.

The trouble with hyphenation is, what do you do the following generation? I know people are bad at thinking about the future, but come on, you just have to imagine this happening one more time. In fact, the brutally patrilineal Greeks and Romans and Chinese were more advanced than us in recognizing a simple truth about exponential growth. Your ancestors grow like 2^N, which means their contribution gets diluted like 1/(2^N), unless you pick an arbitrary rule and stick with it.

With the exception of the Crazy Rich Asians movie. Maybe the Chinese taking over Hollywood will slowly purge the toxins from our society. Lol. Lmao.

Sometimes, as with the Habsburgs, it becomes cringe.

If this sounds familiar, it should. Whenever I read about first century Rome I always come away with a weirdly twentieth century vibe.

Yes, I've read the whole thing cover-to-cover. What? Why are you looking at me like that? There was a pandemic happening, okay?

This is the most criminally underread blog on the internet

Thanks Psmiths. Your essays and discussion is even better than the bookshelf itself. I appreciate the final bit pointing out that what we see and admire most in Greek and Roman "golden ages" is the momentary splendor before it all starts to crash in on itself. Ditto Victorian England. And Pax Americana?

Keep it up; every post is a wonderful invitation to think more deeply.