Central Banking 101, Joseph Wang (Self-Published, 2021)

The greatest gift bestowed by admittance to elite institutions is that you stop being overawed by them. For instance, there was a time when upon hearing “so-and-so is a Rhodes Scholar,” I would have assumed that so-and-so was a very impressive person indeed. Nowadays I know quite a lot of former Rhodes Scholars, and have seen firsthand that some of them are extremely mediocre individuals, so meeting a new one doesn’t faze me much. My own cursus honorum through America’s centers of prestige has been slow and circuitous, which means I’ve gotten to enjoy progressive disenchantment with the centers of power. Trust me, you folks aren’t missing much.

I have a theory that this is why Twitter has been so destabilizing to so many societies, and why it may yet be the end of ours. Twitter offers a peek behind the curtain — not just to a lucky few,1 but to everybody. We’re used to elected officials acting like buffoons, but on Twitter you can see our real rulers humiliating themselves. Tech moguls, four-star generals, cultural tastemakers, foundation trustees, former heads of spy agencies, all of them behaving like insane idiots, posting their most vapid thoughts, and getting in petty fights with “VapeGroyper420.” There’s a reason most monarchies have made lèse-majesté a crime, there’s a level at which no regime can survive unless everybody pretends that the rulers are demigods. To have the kings be revealed as mere men who bleed, panic, and have tawdry love affairs is to rock the monarchic regime at its foundations. But Twitter is worse than that, it’s like a hidden camera in the king’s bedroom, but they do it to themselves. Moreover it seems likely that regimes like ours which legitimate themselves with a meritocratic justification are especially fragile to this form of disenchantment.

This is also why the COVID pandemic was so damaging to our government’s legitimacy. I’ve been inside elite institutions of many different sorts, and discovered the horrible truth that most of the people in them are just ordinary people making it up as they go along, but one place I hadn’t quite made it yet was the top of our disease control agencies.2 So in a bit of naïveté analogous to Gell-Mann amnesia, I just assumed that there was some secret wing of the Centers for Disease Control which housed men-in-black who would rappel out of helicopters and summarily execute everybody in Wuhan who had ever touched a bat. And I was genuinely a little bit surprised and disappointed when instead they were caught with their pants down, and a bunch of weirdos on the internet turned out to be the real experts (the silver lining to this is that now we all get to be amateur scientists).

So much for public health. But if there’s one institution which still manages to shroud itself in mystery while secretly pulling all the strings, surely it’s the Federal Reserve. You can tell people take it seriously because of all the conspiracy theories that surround it (conspiracy theories are the highest form of flattery). And there’s a lot to get conspiratorial about — the Fed manages to combine two things that rarely go together but which both impress people: technocratic mastery and arcane ritual. The Fed employs a research staff of thousands which meticulously gather and analyze data about every aspect of the economy, and they have an Open Market Committee whose meeting minutes are laden with nuanced double-meanings that would make a Ming dynasty courtier blush, and which are accordingly parsed with an attention to detail once reserved for Politburo speeches.

And they also control all of our money! Is it any wonder that people go a little bit crazy whenever they think about the Fed? I can’t think of a more natural target for the recurring cycles of ineffectual populist ire that characterize American politics. So it is with great regret that I’m here to report that they, too, are making it all up as they go along.

I learned this from the book I’m reviewing, Central Banking 101, by Joseph Wang. Wang is a former Fed economist turned prolific Twitter poster, and he’s an institutional loyalist, or at least I think he is. It’s hard to tell if “these people have no real idea what they’re doing” is supposed to be the Straussian esoteric message of this book, or whether it’s something he just let slip, but either way it’s there. Most criticisms of the Fed are written by insane people or by ideological cranks. This one, whether it was meant to be a criticism or not, is written by a deeply sympathetic former employee, and that’s what makes it so interesting.3

This is a book about the Fed by somebody who loves the Fed, but he’s also a guy who knows where all the bodies are metaphorically buried, and that turns out to be the magic combination. Wang worked on the Open Market Trading Desk (a.k.a. “The Desk”), which is the part of the Federal Reserve charged with turning policy into reality by actually doing things in the real world. How things actually happen is a piece of the story that most writing about the Fed glosses over. You read a lot of stuff in the business press that says things like, “the Federal Reserve decided to change the overnight interest rate to 3.75%,” but how they do that is left weirdly vague. The omission is inexcusable, because as Wang’s book teaches us, it’s both one of the most interesting parts of the story and one of the most disturbing.

Consider one of the Federal Reserve’s jobs: conducting monetary policy in accordance with its “dual mandate” of maximizing employment while maintaining stable prices. Historically this was viewed as something of a tradeoff (less unemployment meant more inflation, and vice versa, in accordance with the Phillips Curve). But these days our court macroeconomists believe that if inflation is held at the suspiciously-round number of 2% per annum, then that is low enough to avoid most of the downsides of inflation in practice, high enough to produce durably low unemployment, and best of all predictable enough that businesses and individuals can make plans for the future and calculate long-term internal rates of return.

The way that interest rates affect the rate of inflation is also somewhat murky and indistinct, but there is presumably some interest rate that will send inflation creeping upwards, and another one that will have it creeping downwards, and one right in the middle (called r*) that will keep it stable. The Fed employs an army of economists to try to figure out what r* is, and then adjusts interest rates accordingly to meet their 2% target.

Haha! Did you catch that? I just did it to you, the thing that all writing about the Federal Reserve does. I said “and then adjusts interest rates accordingly…” without saying how on earth they can do that, and you nodded right along. But an interest rate comes out of the sum of all the decisions made by people borrowing and lending money across the whole economy, so how exactly can the Fed control it?

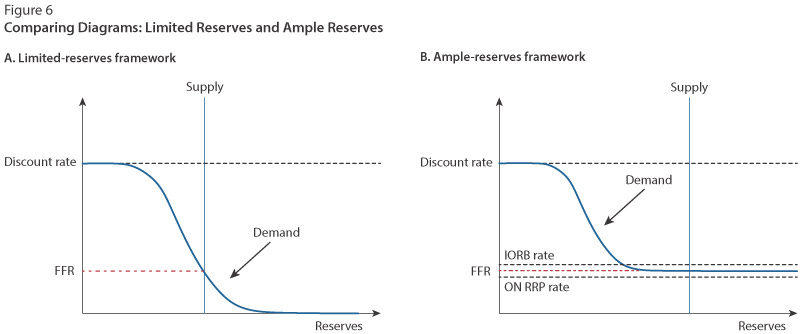

The historical answer is that the Fed did this by tinkering with the level of bank reserves via “open market operations,” primarily buying and selling treasury bills. Banks have regulatory requirements that a certain percentage of their deposits be held as reserves with the central bank.4 This creates a demand for central bank reserves among financial institutions, and means that if the Fed can estimate the demand curve for reserves, then by changing the amount of reserves in the system it can change the willingness of banks to lend reserves to each other. That willingness manifests as an interest rate — the overnight rate for interbank reserve lending, also called the Federal Funds Rate. Changes in the Federal Funds Rate then ripple through the economy and affect all the other interest rates.

That’s the traditional answer, and you will still see it in old textbooks, but it’s now completely wrong. You may remember that back during the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed embarked on a program called “quantitative easing,” wherein it purchased trillions of dollars of financial assets in a feverish attempt to give the economy additional stimulus. An important side-effect of this program is that it massively ballooned the quantity of central bank reserves, such that we’ve shifted entirely off the part of the demand curve with non-negligible slope, and tinkering with the amount outstanding no longer has any effect on the Federal Funds Rate. Basically moving from the picture on the left to the picture on the right:

Today, the Fed controls short-term interest rates in a completely new way, using completely new powers. The most important of these is the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Facility (ON-RRP), which is a program that permits a wide variety of market participants to lend financial assets to the Fed and get them back the next day. Since lending to the Fed is “risk free,” nobody is going to lend things to private entities for less than what the Fed is offering, and so the ON-RRP effectively sets a floor on short-term interest rates. There are other techniques too, also new since 2008, most of them involving creatively reinterpreting some aspect of the Fed’s statutory authority to put pressure on a critical node of the financial system, to get the result it wants in a roundabout way.

What is my point with all of this? My point is that beneath the interface of “setting interest rates,” the implementation of what the Fed actually does has drastically changed. Most of the new stuff had never been tried before, some of it was quite controversial within the central banking community, some of it they weren’t quite sure whether or not it would work. I used to think of the Federal Reserve as a group of scientists in white lab coats standing around looking at a machine, turning one big dial up and down. But in fact, there’s a lot of “engineering” going on as well, and a lot of throwing stuff against the wall to see what sticks.

They’re also slowly adding more dials. If you’re old like me, you remember Japan’s “lost decade” of the 1990s, when interest rates were at zero but the economy stubbornly refused to move. There was a lot of speculation about what might happen if the United States central bank ever found itself in a similar position — back against the wall, rates already rock bottom and no room for maneuver. The answer came in 2008: in the grips of a financial crisis that had the potential to be seriously deflationary, the Fed decided to reach across the yield curve and start controlling long-term interest rates as well.

This was a big move: the Fed had never done this before, some even claimed that the Fed didn’t have the legal authority to do this.5 Short-term interest rates are controlled by the Fed, but long-term interest rates are set by the market. They encode information about what the expected future course of short-term rates,6 but they also incorporate a “term premium” that models the cost of having your money locked up and inaccessible (including both the opportunity cost and the cost imposed by inflation). In 2008 the Fed began trying to affect these rates directly by buying trillions of dollars worth of longer-dated financial assets. See if you can spot the point on this graph where the quantitative easing program began.

Is this good? Is this bad? Does it actually increase economic activity? Are there terrible long-term side-effects? The short answer is that nobody knows, but we are trying it anyway. This internal Fed report suggests that quantitative easing has had a big effect on the prices of financial assets but a small effect on economic activity. Does this mean that the Federal Reserve’s unconventional monetary policy is responsible for NFTs? But wait, here’s a different Fed report which says that QE totally did work. In fact, Wang cites both of these reports at different points in his book to argue both sides of the question (not in a deliberate “some say… others say…” way, but in an “I forgot that I espoused the opposite opinion a hundred pages ago” way). He has no idea whether QE works, nor do I, nor does anybody. Economies are big and complicated, and almost impossible to run controlled experiments on, which is why economics will never be a real science. If you hit the engine with a hammer, does it make the sound go away?

Central bankers around the world talk to each other a lot, and frequently people will try out new interventions in one country before rolling out a wider release. And the place that most of these things get tried out is Japan. The Bank of Japan is astonishingly aggressive, they invented QE and they’ve also pushed it to its furthest limit so far. The US Fed has purchased a few trillion dollars in financial assets, which might seem like a lot, but the BOJ has purchased assets amounting to more than 100% of Japan’s GDP. In doing so, they have annihilated the Japanese bond market. Japanese bond prices are not set by the market, they’re set by the central bank, and there are now days when no Japanese government bonds are traded at all. Is this bad? Is this fine? Nobody knows!

The ultimate form of quantitative easing is the ominously named “Yield Curve Control” (YCC), unsurprisingly also pioneered by the Bank of Japan. The idea behind YCC is that the central bank just announces its intentions as to what interest rates shall be at each maturity, and then dares the market to make it otherwise. So long as the central bank is willing to back up its words with an infinite firehose of QE (or QT in the opposite case), market participants are likely to heed Martin Zweig’s mantra, “Don’t fight the Fed,” and go along with it. Sure enough, when the Bank of Japan tried this out, the announcement alone was enough to make interest rates be what they wanted. Expect this to be coming to America soon.

If you missed all these changes, don’t feel too bad. One of the Fed’s tricks is concealing big changes in its toolkit (or its mission7) within announcements that sound like they’re just tweaks to low-level implementation details. When you read something like “Open Market Desk to conduct Reverse Subordinated FX-Swap Repo Credit Facilities,” it can be hard to tell whether that’s a big deal or not, and in fact it can be hard for actual professionals to figure it out too. And some of the biggest recent changes in the Fed’s behavior all sound like that, and moreover have nothing to do with controlling interest rates at all…

Besides its dual mandate for conducting monetary policy, another of the Fed’s traditional missions is preventing bank runs by serving as a lender of last resort to distressed banks. Then in 2008, it quietly also began guaranteeing the primary dealers8 (via the Primary Dealer Credit Facility), the money market funds (via the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility), and a huge set of securitization vehicles (via the Commercial Paper Funding Facility and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility). All of this is perfectly legal — section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act gives the Fed the power to lend to essentially anyone for essentially any reason. The real fun came in 2020, when the Fed announced the Primary and Secondary Corporate Credit Facilities, wherein it directly purchased corporate bonds from random businesses.

That last one is pretty weird, and pretty unlike what the Fed has done before (you’ll be unsurprised to hear that it was also pioneered by the Bank of Japan,9 living life on the edge). The argument in favor of this policy is that it’s just monetary policy by other means — before the Fed would stimulate the economy by lowering the borrowing costs for corporations by pushing down interest rates; now the Fed is lowering their borrowing costs directly, by buying their debt. The obvious downside is that it means the price of a bond in some sense no longer tells you anything about the health of the company that issued it. Another whole class of financial assets are no longer really communicating information, but instead implicitly being guaranteed by the central bank.10 Is that actually a problem? Will everything go great? Will we regret it someday? Again, nobody knows!

The biggest surprise to me was that it isn’t just the US economy that the Fed is backstopping. During both the 2008 and 2020 crises, the Fed set up FX swap lines with “friendly” central banks, enabling them to rapidly provide dollar liquidity to foreign commercial banks in participating nations. In some sense this makes all the sense in the world. The offshore dollar economy is one of the major pillars of American hegemony, and extending the Fed’s umbrella over foreign banks deepens our already-significant influence over the entire dollar trading bloc.11 Do we have a robust theoretical understanding of the long-term consequences, or even a good historical analogue to work off of? Lol. Lmao.

In the end, it all comes down to what your theory of financial crises is. Most of these crises involve a particular mechanism that sets them apart — junk bonds, or subprime loans, or jpegs of bored-looking apes, or whatever — and much of the journalistic analysis of a crisis hyper-focuses on these details. It’s easy to form a view of the world where the financial system is a basically rational and totally-understood system, except there was this tiny regulatory oversight involving junk bonds… then later another one involving collateralized debt obligations and credit-default swaps…then later another one, etc. This view of the world will naturally incline you to a view where financial crises can be solved via technocratic means: every time we tinker with reserve ratios or add government backstops to a new part of the economy in the aftermath of one of these crises, we are closing one of a finite set of loopholes and asymptotically approaching a world where financial crises are impossible.

There is another view of the world, one which I prefer. The financial system is a game of Nomic played between human beings with inconceivable amounts of money on the line. The rules and meta-rules allow for essentially unbounded emergent complexity, like a Turing-complete programming language, or the axioms of Peano arithmetic. Most of the specific mechanisms involved in later financial crises didn’t even exist during earlier ones. Every regulatory attempt to close a loophole creates another one, like vainly adding sentences to a Gödelian system. The new ingredient in every crisis isn’t new at all, it’s periodic: human psychology. The “mechanical” preconditions for a crisis are always present, what waxes and wanes is the balance between greed and fear. The timescale between crises is determined by generations, by careers, and by the duration of human memory, and when things tip far enough in the direction of greed, very smart people convince themselves in droves that things have totally changed, and a new kind of asset has been invented that always appreciates and has no risk.

All of which makes it so exciting that a large and influential contingent of the central banking world now believes in something called “modern monetary theory” (MMT). MMT holds that sovereign debt crises are literally impossible if you know what you’re doing, and that fiscal deficits do not matter at all. Maybe they’re right, and this time really is different. Maybe they’re wrong, and this is exactly the kind of thing you expect people to say before a sovereign debt crisis. I have no idea, and neither does anybody at the Fed, but we’ll all find out together.

And that lucky few have much to gain by maintaining the charade. A stable ruling class is one that has much to offer potential class traitors, so they don’t get any ideas. It’s when the goodies dry up, whether due to elite overproduction or to a real reduction in the spoils available, that things fall apart.

That’s not quite true: I did once attend an invite-only conference at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. The food was awful, and I wasn’t even able to find the lab where they created crack cocaine, HIV, and Lyme disease.

The closest Wang ever comes to criticizing central bankers outright is in his discussion of CBDC (central bank digital currencies). In a casual aside, he first gently eviscerates the pretexts commonly advanced for CBDCs, then denounces them as one of the greatest government violations of liberty ever conceived. I am not a goldbug or a bitcoin guy, so I had never given CBDCs much thought, but after reading Wang the acronym makes me instinctively reach for my pitchfork.

Conveniently, as the primary regulator for the banking system, these reserve requirements are…also set by the Fed.

Joke’s on them! The Fed’s mandate is to ensure full employment and stable prices, and those terms are both vague enough, and the question of what leads to full employment and stables prices sufficiently controversial, that I suspect the Fed can do whatever it wants. I’m sure there’s some fascinating Supreme Court doctrine or test which says that the Fed can’t nuke Burundi merely because they consider it necessary to maintaining full employment and stable prices, but then again…maybe there isn’t.

Another source of information about this is short-term interest rate futures. That’s right, you can buy a futures contract on what the 3-month interest rate will be 6 months from now. It’s actually a very useful financial instrument.

Ridiculous! The Fed has never changes its mission of ensuring full employment and stable prices, it’s just the things you need to do to ensure full employment and stable prices that have changed.

Primary dealers are large financial institutions that basically act as market-makers for government securities.

Why is it always the Bank of Japan? I dunno, you tell me.

This is both more and less of a big deal than the anti-Fed alarmists make it sound. The total size of the Fed intervention in the market for corporate debt is tiny in relative terms — they owned something like 0.1% of corporate bonds at their peak. But the effect this had on corporate bond yields was enormous, which presumably means that everybody interpreted it as an implicit backstop.

A lawyer friend of mine recalls that on the first day of his securities law class, the professor walked in and announced, “Welcome to the only class offered at this school that will be relevant anywhere on earth you choose to live.”

Wonderful review. My experience in econ academia matches your experience well: many will admit they have no idea what is going on, and that there is no real theory anyone can point to to make sense of the decisions.

No serious economists believe in MMT. If your guy believes in MMT, it follows that he's not a serious economist. He can still have insights into the nitty-gritty of how the Fed operates, but be vary of grand conclusions.