REVIEW: Scaling People, by Claire Hughes Johnson

Scaling People: Tactics for Management and Company Building, Claire Hughes Johnson (Stripe Press, 2023).

This is a bad book. Usually we review books that we like. Sometimes we make an exception and review a book we don’t like, but which is nonetheless extremely interesting. Unfortunately, this book isn’t interesting either. What it is is important, both for what it tells us about some trends in Silicon Valley corporate management and about the broader ideology of the American ruling class.

First, a methodological note: in preparing to write this book review, I interviewed former leaders in Stripe’s engineering and operations divisions who confirmed to me that the practices described in this book bear little resemblance to how Stripe is actually run. This doesn’t surprise me, but it also doesn’t matter for our purposes. Let’s accept the book at face value, what is this book aiming to be?

At the end of the introduction, the author, former Stripe COO Claire Hughes Johnson, says this:

There’s a Pablo Picasso quote we like to repeat at Stripe: “When art critics get together, they talk about Form and Structure and Meaning. When painters get together, they talk about where you can buy cheap turpentine.” Sometimes you want to read a book about Picasso’s life, and sometimes you just want to know where to buy the cheapest turpentine. Consider this the latter: an insider’s guide to management turpentine.

It’s a catchy line: where to buy turpentine. It sounds pragmatic, gritty, and down-to-earth. But the really clever thing about this analogy is that sourcing turpentine is also repeatable, objective, and generic. An artist needs turpentine whether he’s painting cats or boats, whether his paintings are impressionistic or abstract, whether he’s a novice or a master. What Johnson is promising us is “management turpentine” — repeatable, objective, domain-agnostic techniques for the organization and motivation of human beings. That certainly sounds very useful if she can pull it off.

It also fits very well with the zeitgeist. Our society loves the idea of generic, domain-agnostic expertise that’s applicable to any situation. It’s the whole idea behind private equity, or behind Jack Welch’s tenure at General Electric, that being a corporate executive is a transferable skillset and that it doesn’t matter whether the company in question makes toasters or nuclear reactors.1 It’s also why we’ve placed control of our society in the hands of a class of highly-credentialed meritocrats who, as Helen Andrews has observed, don’t know much at all about anything in particular. And finally, it’s why those meritocrats tend to pursue post-collegiate training in domains like law and finance and consulting — fields concerned with the organization and allocation of productive activity as opposed to the production of anything in particular.

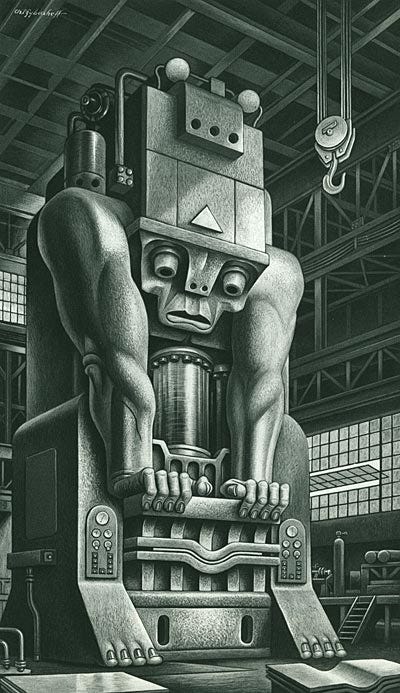

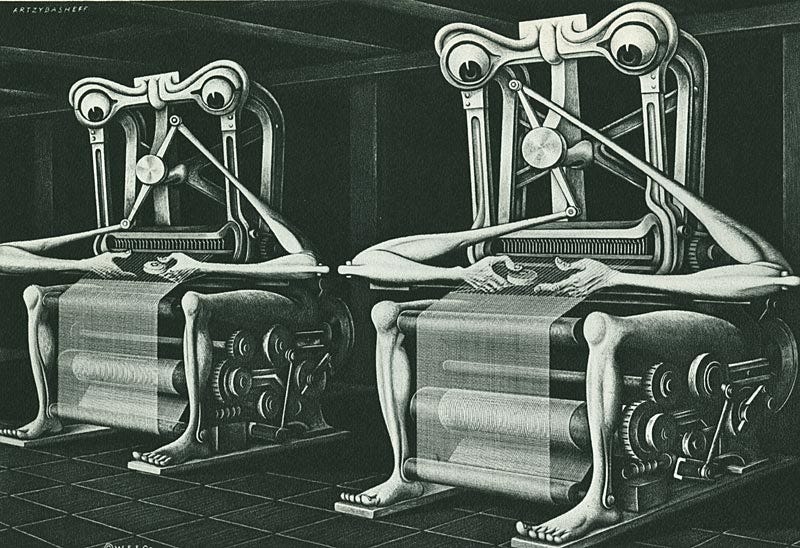

In the world of management, the ideology of generic, domain-agnostic expertise first made its appearance in the late 19th century under the name of “scientific management,” or “Taylorism” after its godfather Frederick Winslow Taylor. Taylor’s insight was that the same engineering principles used to design a more economical or efficient product could just as well be applied to the shop floor itself. In his view, the workers, overseers, and production processes of a factory all combined to form a great living machine, and that machine could be optimized and made more efficient by an application of scientific attitudes.

Taylor was unpopular in his own day and is even less popular today, because his particular brand of optimization of the great living machine was all about stripping autonomy (or as Marx would say, “control and conscious direction”) from workers. But the particular kind of optimization he advocated is less important than the conceptual breakthrough that while a nail factory and a car factory might look very different on the surface, they are both governed by the same set of abstract laws: laws of time and motion, concurrency, bottlenecks, worker motivation and so on. A master of those laws could optimize a nail factory, and then go on to optimize a car factory, and could do both without knowing very much at all about nails or cars.

Who could have a problem with that? Even I don’t think it’s entirely wrong — I may have misgivings about the sheer volume of people going into fields like management consulting, but I’ll admit that there remains alpha in asking a smart and incisive outsider to take a look at your operation and tell you what seems crazy. The trouble comes with confusing that sporadic, occasional sanity-check with the actual business of leading a team of people who are working together to achieve an objective. Because, get this, it’s impossible to lead such a team without a deep understanding of the details of every person’s tasks

It’s surreal to me that this point has to be made, yet somehow it does. If the team you lead makes nails, you need to know everything there is to know about making nails. If the team you lead operates a restaurant, you need to be an expert, not in “management”, but in restaurants. If the team you lead sells mortgage-backed derivatives, you better know a heck of a lot about finance in general, mortgages in particular, the art of sales, and the specific world of selling financial instruments. There are a thousand reasons why this is true, but consider just one: a subordinate is failing at a task, and tells you that it isn’t because he’s lazy or unqualified but because the task is unexpectedly difficult. How on earth can a manager evaluate this claim without being able to do the job himself?

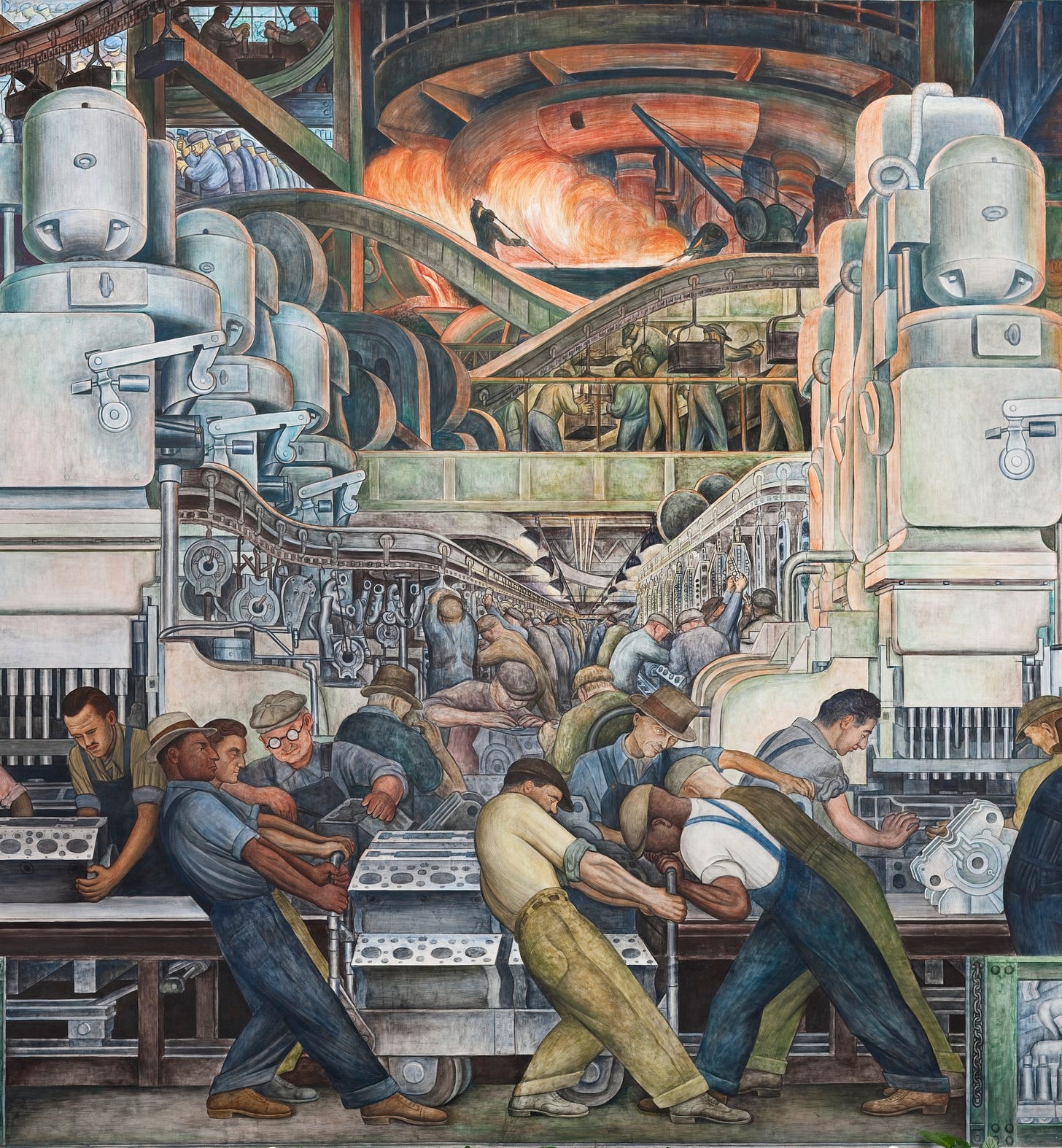

There’s another, very different reason managers need to be experts in whatever it is their team is doing, and it has to do with morale. A subordinate in any sort of hierarchical organization needs to see that his superior can do his own job as well or better than he can. Almost everybody gets this. In a high-pressure commercial kitchen, if a chef or sous-chef doesn’t like the performance of one of their line cooks, they will often leap in, take over that cook’s station, and begin “expediting.” This has a dual purpose: it both relieves a genuine production bottleneck, and also acts as a showy demonstration of prowess, reminding everybody that they got to be the boss through excellence. At the better tech companies, those managing software engineers are always former engineers themselves, and often the very best of the lot. Just like a chef would do, an engineering manager needs to be able to seize a computer and begin expediting under pressure, both to solve a real problem and as a dominance display. But it’s not just about keeping the troops in line, it’s about inspiring them. Nothing motivates a soldier like seeing his commander leading the charge, weapon in hand.2

Despite this view being out of fashion today, most organizations retain a residual awareness that leaders should have a superset of the skills of the people they’re leading.3 So the only thing that really could serve as “management turpentine,” a transferable set of management techniques applicable to any domain, is narrowly-tailored advice for how to deal with people, how to motivate, direct, and control them. And so, by and large, that’s what management books like this one offer — techniques for the one part of the job generic enough to benefit from this kind of advice. But is it really so generic?

A nanosecond’s reflection will tell you that the techniques needed to manage computer programmers, movie actors, and the boom-town roughnecks that inspired Conan the Barbarian are going to be very different. What if we restrict our analysis to just one category, say the computer programmers?4 Well, consider another similarly restrictive category: children. The great limitation of parenting books is, as every parent of more than one child knows, that children are extremely different from one another. One child may need strict discipline, while another actually needs to be encouraged to take rules less seriously; one needs to be reassured constantly and showered with love, while another needs to have firm boundaries. The techniques that work brilliantly with one child will not work unmodified with another. If the goal is the Aristotelian mean, then some need to be nudged to one side, and others in the opposite direction.

If that’s the way it is with kids, imagine how much more so this all applies to adults, who in addition to having different innate personalities and temperaments and aptitudes also carry with them extensive life histories, experiences, and scar tissue. Any generic advice, any “management turpentine,” needs to be heavily customized to the personalities and the dynamics of a particular team. But the catch is that mastering the ability to apply this sort of generic management advice in a particular situation is pretty much just the same thing as mastering management itself.

To a very great degree, management just is the art of taking a set of discordant personalities and welding them into a harmonious whole. A great manager sizes up his or her team, sees the ambitious go-getter, the resentful and self-defeating genius, the timid and awkward newbie with leadership potential, the lazy slob who secretly glues them all together — sees not just these categories but sees the individuals and the unique ways they subvert these archetypes, and instantly and intuitively knows how to fuse them into a machine for achieving a common purpose. Or as Hilaire Belloc once put it:

There is one element in the [management of men] which is all-important, and the possession of which is a gift, like the gift of verse or “eye” in a sport. It is not to be prayed for. It is not to be acquired. It is granted by the unseen powers. This element is that which you have in the good management of a pack of hounds, or in any other kind of good generalship. It consists in a mixture of detailed and general appreciation; for when those two faculties are combined — the faculty of seeing the individual, the faculty of seeing the whole — you have the genius of the human helmsman; as rare a sort of genius as there is among men.

But why does he say that this particular talent is not to be acquired? Go back to Johnson’s line about the management turpentine and read it again, but this time note how deftly the magic trick is performed. Do you see it? Hey presto, there are only two options as to what a book on painting could be about — “Form and Structure and Meaning,” or where to buy turpentine. This is important, because left to your own devices you might prefer a third possibility: namely a book about how to make great art. But as soon as you say it, it becomes clear why that option needs to be hidden from view — no such book has ever existed, no such book can exist, you can’t learn to make great art from a book.

Unfortunately the same is true of being a great manager, and Johnson, to her credit, implicitly admits this along the way. Why can’t you learn it from a book? Well the sage 莊子 once told a story about a wheelwright:

Duke Huan was reading a book in the hall. Wheelwright Pian, who had been chiseling a wheel in the courtyard below, set down his tools and climbed the stairs to ask Duke Huan, “may I ask you, my Lord, what is this you are reading?”

“The words of sages,” the Duke responded. The wheelwright continued, “Are these sages alive?” “They are already dead,” came the reply. Wheelwright Pian persisted, “That means you are reading the dregs of long gone men, aren’t you?” An exasperated Duke Huan retorted, “How does a wheelwright get to have opinions on the books I read? If you can explain yourself I’ll let it pass, otherwise, it’s death for you.”

Wheelwright Pian said, “In my case I see things in terms of my own work. When I chisel at a wheel, if I go slow the chisel slides and does not stay put; if I hurry, it jams and doesn’t move properly. When it is neither too slow nor too fast I can feel it in my hand and respond to it from my heart, and the wheels come out right. My mouth cannot describe it in words. You just have to know how it is. It is something that I cannot teach to my son and my son cannot learn it from me. So I have gone on for 70 years, growing old chiseling wheels. The men of old died in possession of what they knew and took their knowledge with them to the grave. And so, my Lord, what you are reading is only their dregs that they left behind.”

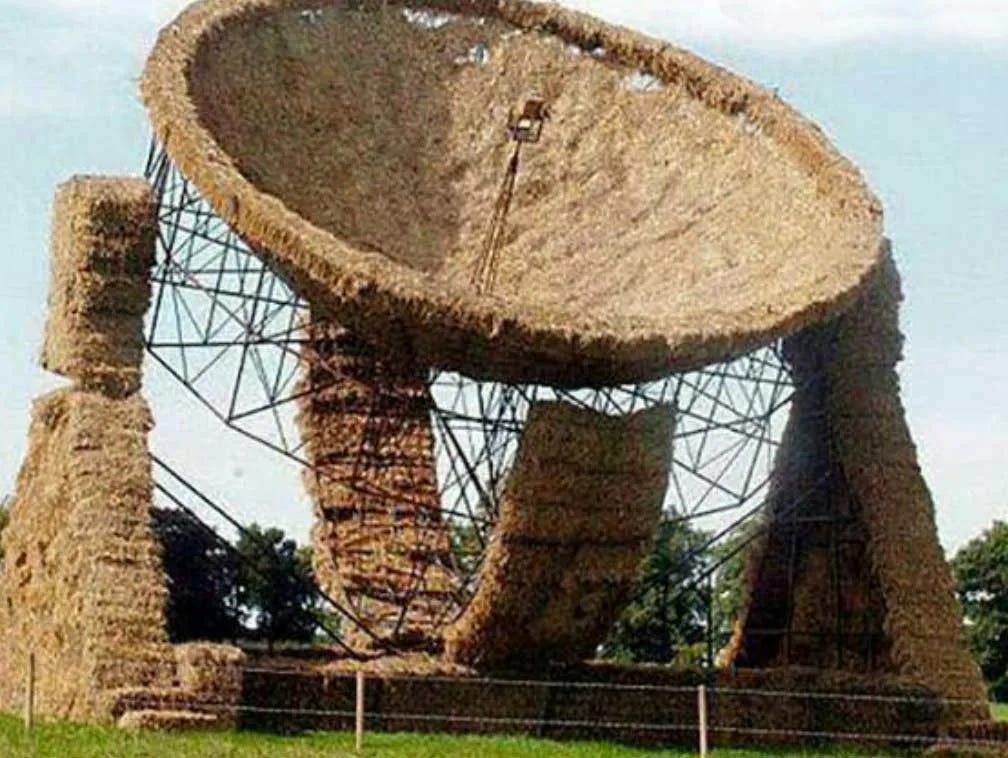

That’s right, being a great manager is actually a kind of process knowledge, and like most process knowledge can’t be written down. Oh, you can write down some things that you’ve seen great managers do, much like the participants in a cargo cult can write down the steps to building an imitation airfield, but the reasons they did those things then, and other things at other times, will remain obscure to you. They may even be obscure to the great manager himself.

This truth mostly goes unspoken because our civilization is allergic to the idea that there are forms of knowledge that can’t be written down in books. Various cranky reactionaries have complained that this is due to unexamined rationalistic/constructivist metaphysical premises embedded in our ruling ideology. But I have an alternate explanation which is at once more cynical, and also more prosaic: the existence of forms of knowledge that cannot be imparted by our credentialing institutions would threaten the legitimacy of our system of rule, which derives much of its moral and affective sympathies from the claim that it’s smarter and better and more efficient than anybody else.5

If management is a domain-agnostic set of skills that can be learned at Harvard, this is extremely convenient for the class of interchangeable, domain-agnostic meritocrats who went to Harvard. Conversely, if management is a skill that comes through hard toil in a particular field for a long time, or even worse an innate skill relatively uncorrelated with one’s position in the meritocratic hierarchy, then that is detrimental to the class interests of the people who write all of the books and make all of the rules.

Johnson is of that class. We know this because she presents her educational credentials and cursus honorum on practically the first page of this book, like a 17th century aristocrat rattling off his family titles and a list of the battles his ancestors fought in. We also know this because she signals fealty to the DEI church by mentioning that one McKinsey study that everybody always mentions.6 But it only gets that little cursory nod, because it’s beneath her station as a true noble to be excessively pious. The inquisition tends to be staffed by people from more middling backgrounds.

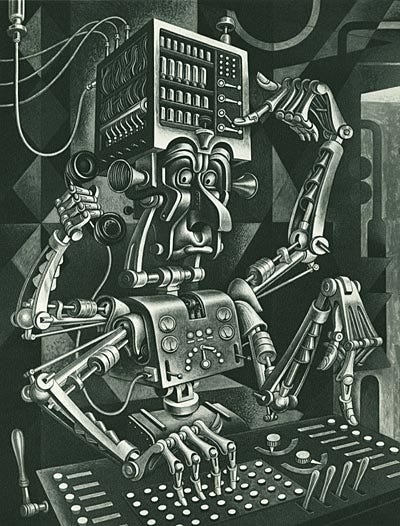

One thing this class of meritocrats is quite bad at is autonomously coming up with their own values or objectives and then trying to achieve them. This is unsurprising, since the way you get into the meritocracy is by diligently following a track laid down by others — good grades in school, just the right extracurriculars, college application essays that express the approved sentiments in the approved fashion, four years at the right university, and so on. These people are very good at following orders, and even better at acting as a transmission belt that passes along orders flowing in from above, but figuring out what ought to be done in the first place is not their strong suit.7

So this is a book by and for that class of dutiful middle managers, and to its great credit it never tries to pretend otherwise. In fact it even sets up a dichotomy between “management” and “leadership” and then says “this is a management book.” But things go off the rails when, in the course of this stage-setting, it tries to describe what leadership is and gets it horribly, destructively wrong. It’s possible this is one of those “darkness cannot comprehend light” situations. In my experience, the best leaders come to love and appreciate good managers (sometimes they even are good managers themselves), just as any general knows that his army would be a disorganized mob in the absence of company and battalion commanders. However even the best managers, and I have no doubt that Johnson is a very good one, tend to view their leaders almost as an alien species, albeit one they cannot live without.

Thus, when you ask a good manager what leadership is, you tend to get some screwy answers. Here’s Johnson’s definition: “Leadership is disappointing people at a rate they can absorb.” This saying is pernicious because it sounds oh so clever and canny, and because it contains a kernel of truth: leadership does often involve disappointing people. The place that sentence turns nasty is at the end. Reading it feels to me like having a mouthful of something tasty and then suddenly spotting the worms and maggots writhing in the bit of it that remains on your plate.

The awful barb in this faux-insightful quip is the “at a rate they can absorb” part. Think for a second and it becomes clear that an equivalent phrasing would be: “lie to people or conceal the truth from them if you don’t think they can handle it.” I’d say I’m surprised by that level of disrespect and condescension towards one’s subordinates, except that Johnson then immediately goes on to say, “a saying I’ve repeated often to colleagues and direct reports,” so apparently she also thinks they’re too dumb to figure it out.

All the same, it’s hard to blame her, because this surpassingly patronizing attitude that it’s the job of leaders to manipulate their subordinates (for their own good of course) is a fundamental tenet of our ruling ideology. It’s part and parcel of the American ruling class obsession with manipulating social reality to the exclusion of physical reality. Just consider the two definitive crises of the past few years: the SARS2 coronavirus pandemic and the Second Donbass War.

The public health establishment’s response to the new respiratory infection that swept the globe progressed through a few distinct phases, starting with underreaction, eventually switching to overreaction, and ending up like those Japanese marines that occasionally stumble out of the jungles of Borneo, unaware that the war is long over. Nevertheless all these distinct phases share a common thread, which is a belief that good outcomes will result from manipulating the public into doing what’s best for them, rather than just telling them how it is.8 The head-spinning reversals that have destroyed what legitimacy America’s public health institutions retained were all downstream of this tendency.

Our peasant rebels love to point to these flip-flops as evidence of the shakiness of the underlying science. Why else did masks suddenly switch from ineffective or harmful to mandatory? Why did vaccines suddenly switch from risky and ineffective to mandatory? Why did large public gatherings switch from mandatory for all non-racists, to absolutely forbidden, then back to mandatory for all non-racists? As always, the Amerikulaks see the right symptoms and deduce the wrong illness. The science on all of these questions was remarkably consistent throughout these phases: what changed were the directives sent by the nomenklatura, and hence the resulting messaging. The policies kept changing for the same reason that health authorities spent the first critical weeks of the pandemic orchestrating a cover-up — because the goal was never actually to stop the pandemic, the goal was always to manage public perceptions of the pandemic.

The American public health response was all about ignoring biological or logistical realities and hyper-focusing on trying to shape social reality instead. The result has been an endless gamut of failed psyops and ham-handed attempts at reverse psychology that have annihilated public trust and backfired in ways that would be hilarious if they weren’t so dark. I don’t have it in me to dig into all the ways in which the Ukraine crisis has followed the exact same pattern, but suffice it to say that it does.

You can see it in the way that the Ukrainian government (whose operations are meticulously coordinated by the same class of Americans that was in charge of pandemic policy) puts disproportionate energy into showy or cinematic operations designed to make awesome memes. As of this writing, Western media is deluged with hand-wringing articles lamenting that the Ukrainian offensive has the appearance of failure. Not that it is failing, mind you, but that it appears to be falling, which could have implications for morale, popular support, etc., etc. If you can’t quite believe that these people think public relations can defeat an enemy who’s equipped with guns and bombs, remember that a short while ago the same people believed that public relations could defeat a virus.

A few months into the pandemic, Tyler Cowen received a great deal of criticism for innocently asking what the average GRE score was for individuals admitted to a Masters in Public Health program. We don’t have to go as far as Cowen and Andrews in saying these people are dumb to recognize that there might be a bit of a “human capital” issue here.9 Remember the composition of our meritocracy: individuals with high agreeableness, conscientiousness, and fluid intelligence, but not much in the way of actual knowledge about any actual topic. Fighting a pandemic, fighting a war, and making stuff all require actual, detailed, practical knowledge of technical fields. But we have an aristocracy of lawyers, consultants, journalists, and financiers. Are you really surprised that they spend all their time making memes? It’s what they’re good at.10

So back to Johnson: maybe her catastrophically bad advice on leadership can be excused, because really she’s just picking up the ambient vibes of her social class and transmitting them in aphorism form. What could we tell her that would make her better at this? Well, maybe she could take a pointer or two from the man who conquered Europe. Napoleon’s wartime correspondence with his generals has all been published, and the dominant concern that comes up again and again in those letters is…shoes.

Shoes? Yes, you read that right. Napoleon obsessed over every aspect of battlefield logistics, but he paid special attention to shoes. Historians have advanced various reasons for this: perhaps it was because he wanted to ensure his army could march a long way every day, perhaps it was to prevent frostbite and disease, perhaps it was a sort of brown M&M test for his commanders. I suspect he did it for all those reasons, but I also suspect there was one more. I think he did it for the same reason he so often remembered the names and biographical details of individual infantrymen decades after learning them, I think he did it for the same reason he would share food and wine from his own table with his sentries, I think he did it for the same reason he would weep after battles. I think he did it because he actually gave a damn about the people under his charge.

The greatest leadership superpower is actually caring about your subordinates. Many leaders pretend to care, but human beings have exquisitely tuned bullshit detectors, especially for people who want something from us, so there’s no substitute for the genuine article. Management books make this mistake all the time, with advice like “try acting like you care,” as opposed to “try actually caring.” This is partly because these books are all cargo cults,11 partly because actually caring is hard. The people you’re supposed to care about are often disagreeable, unmotivated, selfish, or just plain smelly. The temptation is strong to treat them as tools, or as consumable resources that happen to be human beings. Why am I supposed to care again?

Different civilizations have had different answers to this question. Perhaps you’re supposed to care because of aristocratic noblesse oblige, or perhaps you’re supposed to care because every relationship between superior and subordinate is an icon of the archic yet kenotic relationship between God and creation, the Lord as servant of all. Our society stands alone in not giving superiors much of a reason to care; the ideology of meritocracy has stripped us of it. Every past civilization has recognized an element of chance in who winds up a king and who a peasant, but ours insists that no, those who rule do so because they are deserving. Even worse, it purports to judge those rulers according to a value-free objective standard of “effectiveness.”

It’s hard to imagine a system of rule better designed to produce an attitude of contempt towards subordinates.12 “Don’t these lazy idiots know that I went to Harvard, and that their incompetence is making me look bad?” It starts with the temptation to treat people as resources, to lie to them when convenient, and it only gets worse from there.13 I can’t really blame Johnson for imbibing this attitude, when it’s the spirit that animates our entire regime. But there is an alternative. There is something in the soul of every man that longs for the return of a righteous king. Start acting like him, and people will joyfully follow you into anything.

I once met a guy on a sailing trip, and when I asked what he did, he said, “I’m a corporate executive” and didn’t elaborate. I then asked what his company did, and he just stared at me blankly. I wished I could short his company’s stock, but they had recently been acquired by a large European conglomerate and taken private.

This shows up in places you wouldn't expect to. I was once cast in a show, and quickly came to understand that our director could (and often did) leap onto the stage, snatch a script out of somebody’s hand, and play their part better than they could. For any part. Before he did this to me, I found him annoying and bossy. Afterwards, I would follow him into the Somme.

Fewer and fewer every day though. A United States military friend recently pointed out to me that the high ratio of senior Russian officers killed in Ukraine and Syria speaks well of their military culture, because it means that even their general officers make a custom of occasionally leading from the front (there’s a long history of this in the Russian armed forces). He then reflected bitterly that an American general being killed was simply unthinkable, since to a man they sit in air-conditioned offices and command their troops over satellite link.

Johnson’s book is marketed towards those managing computer programmers, which is interesting since she worked on the operations side of the house and as far was I know has never been in charge of a crew of engineers.

I’ve wondered sometimes whether this might be a structural weakness in our system of rule-by-experts. Every regime runs into problems when harvests fail, barbarians invade, infrastructure degrades, and the Mandate of Heaven begins to slip away. But in most regimes, the ruler is legitimate because he is the Son of Heaven or the Voice of the People or something like that. When legitimacy has its ideological superstructure built around keeping the economy growing and the trains running on time, does it therefore erode more quickly when those things stop happening? I guess we’ll find out…

If you’ve ever read an article of the form, “diversity improves corporate outcomes,” I will wager you that it either cites this study or one of its immediate predecessors.

The study is obviously very low quality and says nothing of the kind. But that isn’t the surprising part to me. The surprising part is that the vast machine that summons studies like this into being has thus far been satisfied by just one. Why hasn’t anybody else gone and produced this result? Surely it would be more convincing if there were more things to cite. I can only conclude that we’re already past the point of Brezhnevite ideological exhaustion, and that even the people who believe this stuff don’t actually bother to read these things.

This is all very much connected to some of Peter Thiel’s writing on “indefinite optimism,” which can almost be defined as the condition your civilization falls into when it’s run by organization kids.

There could be another cause for why the pandemic response focused so heavily on messaging and PR. Remember that the big public health topics of the last few decades have been things like obesity, heart disease, smoking, AIDS, opiate addiction... These all have something very important in common: to a greater or lesser extent, they’re diseases of the will, things people do to themselves, not an implacable, mindless, alien force like a rapidly-spreading virus.

This has a couple big consequences for how public health conceives of its role. First of all, it turns a major part of the public health field into public relations. More insidiously, it shapes their culture to be disdainful and antagonistic towards the public. (I really sympathize with them here — if my job were to spend all day convincing idiots to stop destroying themselves, I’d be disdainful and antagonistic too!)

It seems very likely that all of this sank into the culture of these fields. And so when another challenge arose, they reached for familiar tools. A lot of what happened in America in 2020 suddenly makes more sense once you realize that the average CDC employee wasn’t trained to fight pandemics but to lie to people for their own good.

But also they’re right, these people are dumb.

The human capital issue can easily turn into a vicious cycle too. If a professional field or a social caste celebrates triumphs of messaging and suasion, it will tend to attract people with high verbal intelligence as opposed to people with high quantitative intelligence or strategic cunning. Some of them will wind up in high positions, where they will push even further in the direction of all activities revolving around the manipulation of social reality, and attract more people like themselves.

Something like this is part of the lifecycle of every scientific and artistic community. But when you apply it to a ruling class as a whole, that’s when you get a situation where the best and brightest aren’t obsessing over exponential growth curves or Chinese lab safety procedures, but instead are trying to figure out the perfect way to craft a public service announcement or social media campaign.

Some real “Duke Huan and the Wheelwright” vibes here. Can’t you just imagine some management guru watching a leader yukking it up with his troops, asking one of them, “say, wasn’t it your kid’s birthday yesterday?” and robotically writing down in his Big Book of Management Tips, “Memorize children’s birthdays.”

In the early Middle Ages, French aristocrats would commonly attend village festivals, and wrestle in the mud with their peasants. By the 18th century, they were doing everything they could to avoid ever seeing peasants. Which end of the spectrum do you think our rulers are closer to? Now imagine that the peasants are Trump voters.

In this fallen world, I don’t think true leadership categorically rules out ever lying to people for their own good, but it should be understood as a grave decision with the potential to permanently destroy the trust between leader and follower. A good heuristic might be, “how would I feel about lying to my wife for this reason?”

I think this is a really great essay, and I really enjoyed it.

I do have a criticism, however, in that it sort of falls apart and contradicts itself in the second to last paragraph.

The first reason is somewhat pedantic, but in fact most societies had (have) a reason why their leaders were deserving. Divine right of kings, descent from gods, chosen of god, caste, right of conquest, etc. It just doesn't take long before people start to wonder "Why is he pushing everyone around? Why not me?" and an answer needs to be provided.

More importantly, however, is that you conflate "meritocracy" with "credentialism". Those managers and leaders you describe before, those who can do the job better than their subordinates because they did it before and know it so well, those people have merit. The management school graduate with no experience and a still damp degree, that fellow has merely a credential. He may have some merit when it comes to completing school, but no demonstrated merit in the field he is entering.

I bring that up because I think that is where we got off the rails, confusing merit in one field (getting through school) with merit in any other field. We mistook a credential for merit that can apply anywhere, as though it were the turpentine from the beginning of the essay.

I would wager the issue came from the distinct realms of schooling: job training vs filtering for smart and conscientious. An engineer or a doctor who gets a degree probably can do engineering and doctoring pretty well shortly there after with minimal extra training (at least in the old days.) A manager or English major who gets a degree has merely shown they are intellectually sufficient to get the degree, not that they can actually do anything useful after without a lot of extra training. I expect that once, long ago when relatively few people could cut it in college and most went for job training type things anyway, merit and credentials were a little closer, but lately of course they have greatly diverged.

At any rate, I would argue that although we call what we have a "meritocracy" what we in fact have is a "credentialocracy". Which is awkward to say and embarrassing, so our rulers prefer to claim merit when in fact they eschew merit in favor of, well, doing exactly what you say in this essay. Which was really great! Except for those last two paragraphs :D Don't grant the bastards their claim that what we have is a meritocracy, when those in charge are versions of your executive who doesn't even know what his company does. That's not merit, at least not in any activity worth pursuing.

A most excellent post! If you're familiar with Iain McGilchrist's work (The Master and His Emissary), his analysis of the differences between those who are Right Hemisphere Dominant and Left Hemisphere Dominant (in terms of their thinking and orientation) seems to really overlap with the distinctions you point out between good and bad leaders. (John Carter at Postcards from Barsoom had some posts on this theme, e.g., https://barsoom.substack.com/p/left-and-right-brains-and-politics, as did Winston Smith at Escaping Mass Psychosis, e.g., https://escapingmasspsychosis.substack.com/p/the-master-betrayed-1?s=r.) Your analysis also sheds some interesting light on the growing competency crisis in America (and the West generally), where we've been promoting leaders based on their mastery of symbolic knowledge, but they lack any concrete skills or any ability to tie their academic theories to anything real in any meaningful way; so we have a leadership class that can write bestselling books on leadership full of neat aphorisms, but cannot actually lead anyone in any way that yields tangible, real-world improvements. Add to that all the DEI nonsense and regular Peter Principle tendencies, and you have a surefire recipe for mediocrity.