REVIEW: Kindred, by Rebecca Wragg Sykes

Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art, Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Bloomsbury, 2020).

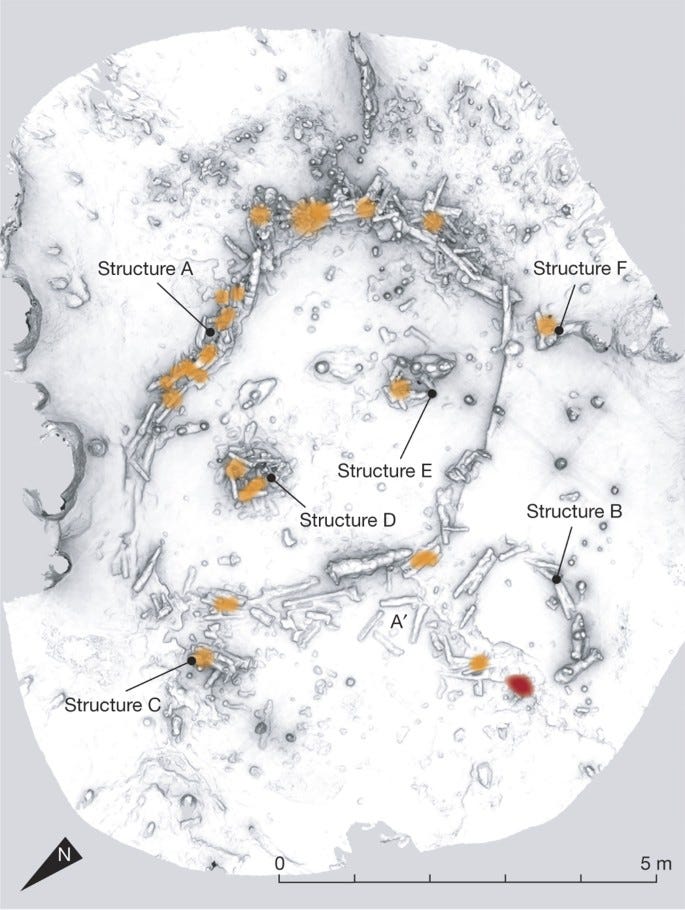

One hundred seventy-five thousand years ago, a group of people carried torches deep into a cave in what is now the southwest of France. There they broke some four hundred stalagmites from the ground and used the central cylindrical pieces — more than two tons of them —to build a pair of enormous circles. The stones were layered atop each other (up to four levels in some places) and carefully braced to build the walls of the rings. In a few places they stacked more stones, for all the world like the ruins of some classical temple, in piles. And then they lit fires, beside and on top of the structure itself. There was no cooking or butchering in the cave, which lies about a thousand feet down a narrow passage, and without any means of venting the smoke of their torches and fires the air must have been choking. But they or their fellows returned more than once to build further fires amidst the stone rings. We don’t know who these people were or why they did any of this. But we have some idea what they looked like, because they were Neanderthals.

Anatomically modern humans existed at this point, but they wouldn’t reach Europe for another hundred thousand years. And for another twenty to fifty thousand years after that, the two kinds of people shared the continent — sometimes competing with each other, sometimes procreating — until Neanderthals disappear from the fossil record about 40,000 years ago. (You’ll note I don’t call anatomically modern humans “our ancestors,” although of course they were, because anyone with non-African descent can trace about 2% of their genome to Neanderthals. It’s not clear whether this ratio indicates only occasional interbreeding, the reduced fertility of males whose parents are genetically dissimilar, the gradual out-competition of Neanderthal genes in a mixed population by better-adapted genes from the newer African arrivals, or something else entirely.) But for 400,000 years (give or take), through several rounds of the advance and retreat of glaciers across the landscape, western Eurasia was peopled only by the Neanderthals. And it was the Neanderthals who built the stone rings in Bruniquel Cave.

I’ve always been fascinated by prehistoric hominins. I trace it to a copy of Lucy that lived right next to my parents’ computer in the days of dialup, and for years I thought I wanted to be a paleoanthropologist. It turns out I have a thing about dust on my hands (and besides I was never all that interested in the issues of comparative skeletal morphology), so I’m very happy as a housewife who reads a lot of books about paleoanthropology. And what I really wanted to know was: forget bats, what is it like to be a Neanderthal?

Rebecca Wragg Sykes doesn’t really answer this, because it’s not a question that can be answered. That gap of understanding is a problem intrinsic to the study of prehistory: if no one knows quite what to make of the plastered skulls from Çatalhöyük ten thousand years ago, how much more difficult to understand the reasoning behind the burial practices of people who lived ten times as long ago and whose brains (let alone minds) may have been quite different from our own? But she tries, and she comes about as close as anyone can until we learn more. And how much we’ve learned already! Not only have we extracted Neanderthal DNA and sequenced their genome, we can analyze the barium in their teeth to tell when they were weaned. We can count micro-layers of soot and mineral deposits on cave ceilings to tell whether evidence of a dozen fires meant a band traveling together or twelve separate visits by an individual or small group. We can look at the patterns of cut marks on the bird bones they left behind and tell they kept raptor talons and long wing feathers, probably for adornment. We can use the tartar on their teeth to determine their diets and even what kind of wood they used for for splinters to clean their teeth. (I shall henceforth consider my semiannual dental cleanings as a kind of modern barbarism designed to shield the intimate details of my life from future scrutiny.) We can’t know what these things meant, but we can guess, and at a certain point, the mere piling-up of material details begins to give a sense of the texture of these people’s lives.

I keep calling them “people,” but we often don’t. Scientific papers, of course, use technical vocabulary, but even in casual conversation we wouldn’t call Lucy a woman; she’s a female australopithecine. We used to point to fire and tool use as the uniquely human characteristics until we found evidence of both all the way back with H. erectus more than a million years ago. Now we’re more likely to suggest that language, art, or burial practices separate the “archaic hominins” from the “ancient people.” But even by those criteria, Neanderthals score about as well as the anatomically modern humans who were their contemporaries. They engaged in long-distance exchange and buried their dead. (H. naledi, an African hominin with interesting mosaic anatomy including modern locomotion but brains about a third the size of ours or Neanderthals’, also buried their dead.) We can’t prove they had language, but they certainly planned and coordinated their hunts and moves across the landscape well ahead of time, their hyoid bones were the same shape as ours, and their FOXP2 gene (mutations to which have been found in modern humans causing serious language impairment) was the same as ours, so there’s no reason to think they didn’t speak. And they probably didn’t leave musical instruments or representational art, but then neither did H. sapiens until quite recently.1

The arrival in Eurasia of full “behavioral modernity,” with representational art and more sophisticated stoneworking techniques, coincides almost perfectly with the disappearance of Neanderthals from the fossil record — but it’s important to distinguish between the arrival of behavioral modernity and the arrival of H. sapiens, who at some sites alternated residence with Neanderthals for thousands of years. There are a number of sites with stone tools and other artifacts (are animal teeth engraved with geometric markings and rubbed with ochre symbolic? are they art?) that date to this period of coexistence and might be Neanderthal or H. sapiens in origin. And tantalizingly, none of the H. sapiens genomes sequenced from this period seem to be ancestral to any living human populations.

My guess (and it is just a guess, though it’s consistent with the evidence and actual experts have guessed this too) is that the disappearance of the Neanderthals was due not to better-adapted H. sapiens genetics but to better-adapted H. sapiens culture. More specifically, a particular better-adapted H. sapiens culture, which conquered, displaced, or simply outcompeted not only the Neanderthals but also the anatomically modern H. sapiens with whom the Neanderthals had been sharing the continent.2 Somewhere, probably in Africa, some group of H. sapiens hit on a revolutionary package of tools and social technologies that allowed them to spread into territory previously held by other hominins — and beyond. In only a few tens of thousands years, the merest blink of an evolutionary eye, they had adapted to every environment on Earth and were on the road to developing sedentarism, agriculture, states, and eventually the very field of paleoanthropology that allows us to study what was left behind.

And it’s what the Neanderthals left behind that fascinates me. Their genes, yes, and their ochred beads, but they also left us at least one monumental stone structure. You can find video of Bruniquel Cave online and it takes only a small stretch of the imagination to transform the cool, steady light of the explorers’ headlamps to ruddy, flickering torchlight. So far into the cool, deep underground world, no sounds would be heard but the pop and crackle of fire, the snap of breaking stone, the labored breathing of people lifting and carrying heavy objects for hours in the increasingly smoky air. We can no more know their purpose in building it than some far future society could identify the purpose of Nôtre-Dame without a written record. But can we doubt there was a purpose?

Which all leads me, inexorably, to my craziest theory. You’ve probably heard of the Denisovans, another archaic human species that, for a time, coexisted and interbred with both Neanderthals and H. sapiens. (I hope someday we’ll know enough about them that someone can write a book like Kindred about them, too, but for the moment we definitely don’t.) What you may not know, though, is that the Denisova hominins get their name from the cave in the Altai where they were discovered, which is itself called after the 18th century hermit Dionysiy (Denis) who lived there for many years in prayer and fasting. He was accompanied in his ascetical labors only by the unbelievably ancient bones of at least six dead people, and probably more, many of whom came from a branch of our human family we never knew existed. One of them, the young woman referred to as Denisova 3, lived between 75,000 and 50,000 years ago. She’s known to us only from a piece of the last bone of her little finger, which was our first evidence of the Denisovans; many of the scientists involved have described the bone as “miraculously” well-preserved. They presumably intended it to be figurative, but perhaps it’s literally accurate. Perhaps through the grace of God and the prayers of the monk Denis, Denisova 3’s fingerbone survived to tell us of the existence of her people. And why? Well, knowledge, maybe, but also so we can pray for them, as well as for the Neanderthals — some of whom, given the extra-African genetic heritage of the Mother of God, must surely be numbered among the ancestors of the Lord. After all, we should remember our kin!

Briefly Noted

I have read a whole lot of other books on human evolution and paleoanthropology, most of which don’t deserve recommendations, let alone their own reviews. Here’s a list of ones I do recommend, in a rough order of how strongly I recommend them:

Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, by David Reich: If you only read one of these books, make it this one. We gave it a joint review here. Reich has a lot more to say about population genetics and human prehistory than about archaic hominins, but his genetics work is absolutely central to our present understanding of Neanderthals and his book does an amazing job of explaining the statistical and laboratory techniques he employs.

The World Before Us: How Science is Revealing a New Story of Our Human Origins, by Tom Higham: Higham has been at the center of several of the most exciting recent discoveries in human evolutionary history, and on the edge of most of the rest of them. This book is the newest on the list, and in a field that’s changing this rapidly that makes a big difference; there are several other recent books that cover some of the same material (most notably by Johannes Krause), but this is the one to read. It also sheds a little more light on what it’s like to do this kind of science in a practical sense and I enjoyed his brief sketches of some of the most famous archeologists, anthropologists, and evolutionary geneticists are like. You can only read the name “Svante Pääbo” so many times before you get a little curious!

The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Vice in Human Evolution, by Richard Wrangham: Mentioned below in Footnote 3; Wrangham draws on the science of animal domestication to argue that the unique feature of H. sapiens was our reduced reactive aggression. There are interesting implications for cultural development and the shifts that took place with the rise of civilization, though Wrangham doesn’t draw them out.

Almost Human: The Astonishing Tale of Homo naledi and the Discovery That Changed Our Human Story, by Lee Berger: Fun mostly as a window on how paleoanthropology is actually done: the story of the excavation of Rising Star cave is crazy.

Shaping Humanity: How Science, Art, and Imagination Help Us Understand Our Origins, by John Gurche: An absolutely gorgeous coffee table book by the man who did the sculptures at the Smithsonian’s Hall of Human Origins (by far my favorite Koch joint). The Neanderthal man pictured above is his reconstruction of Shanidar I, but Gurche has also done most of the other notable hominins, and the book covers both what we know about various species and the artistic process of representing them. When you sculpt Lucy from her bones, how do you make sure that she’s both physically accurate and that she creates the appropriate emotional and aesthetic experience for her audience? Probably the book on this list that’s closest in spirit to Kindred, despite its very different approach. And the pictures are great.

Origins: How Earth’s History Shaped Human History, by Lewis Dartnell: This is actually primarily a book about geology and climate as they impact humanity, but that’s unusual and I found it fascinating.

Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, by Richard Wrangham: I am biased about the importance of cooking to just about everything, but I think Wrangham makes a good case.

Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes, by Svante Pääbo: Speaking of Svante Pääbo! Mostly a memoir, but since the life events are all concerned with ancient genetics (a field in which Pääbo is basically the guy) the science is there too. Extremely readable, and boy does it make me glad I’m not a bench scientist, but he’s done some truly remarkable work. This is a book to read if you’re interested in the history of the field and the individual people involved. Reich and Higham are mostly interested in telling you what we’ve figured out; Pääbo has the story of how. Ignore the rather outré personal life. Fun fact: Pääbo and his biological father, whom he hardly knew growing up, both won the Nobel Prize. Genes, man.

Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth, by Chris Stringer: This one is a decade old, which means it’s full of observations like “this tooth is kind of weird, I wonder what’s up with that” and then you Google and it turns out that actually they’ve extracted DNA from the tooth and what’s up is the guy was 10% Neanderthal. I think it’s still worth checking out if you’re a completionist, though, because Stringer gives some really interesting background on how the field has changed since he hitchhiked around Europe measuring fossils with calipers in 1971. He’s mostly a bones guy, after all, and the paleontology isn’t changing nearly as fast as the genetics.

And of course, if you subscribe to this Substack there’s already a 13% chance you read Razib Khan's Unsupervised Learning, but if you're interested enough in what I have to say about Neanderthals to read to the bitter end and you don't already read Razib, you're missing out. He just did an hourlong podcast that’s just him explaining all of human genetic history (and namedropping half the guys above) and it was great. I have a couple of three month gift subscriptions available if you want one.

There are fascinating suggestions that a set of cave paintings in modern Spain may have been Neanderthal in origin, which would not surprise me at all but is far from accepted.

Primatologist Richard Wrangham argues in The Goodness Paradox that one important element in H. sapiens’ success was a reduction in reactive aggression associated with a broader domestication syndrome. The theory is that Neanderthals were unable to maintain the large group sizes necessary for cumulative cultural evolution to produce complex social technologies and that they stand in the same relationship to us as wolves do to dogs.

I bought the book, thanks. I really liked the other book recommendations. I've read a bunch of those, and I'm now looking forward to reading "The World Before Us". My main reason for writing is to talk about "The Goodness Paradox". This book, more than any other I can think of, changed how I think about human evolution. As you hint at, there seem to be many possible implications (spandrels) of our self domestication that Wrangham doesn't follow up on. Neoteny (staying childlike) and the scrambling of our sexuality, might both be downstream of domestication.

And finally I thought I'd offer you (or maybe your husband) a book that you perhaps have not read. "A Pattern Language" by Christopher Alexander. Lots of ideas in this book are things I sorta knew, but having them fleshed out by someone who had thought about them more was useful. How we build and interact with our living spaces... it's great and I'm sure you'll love the parts about children's spaces. (I added a window seat a few years ago and all the pets and humans in the house love it.)

I know this is an old thread, but any chance you still have gift subscriptions to unsupervised learning? I love the free posts I have read over there.