JOINT REVIEW: Who We Are and How We Got Here, by David Reich

Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, David Reich (Oxford University Press, 2018).

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

Jane: The problem with history is that there just isn’t enough of it. We’ve been around for, what, fifty thousand years? Conservatively.1 And we’ve barely written things down for a tenth of that. Archaeological excavation can take you a little farther back, but as the archaeologists always like to remind us, pots are not people. If you get lucky with a society that made things out of durable materials in a cold and/or dry environment (or you get very lucky with anaerobic preservation of organic materials, like in ice or bogs), maybe you can trace a material culture’s expansion and contraction across time and space. But that won’t tell you whether it’s a function of people moving and taking their stuff with them, or people’s neighbors going “ooh, using string to make patterns on your pots, that’s cool” and copying it. It certainly doesn’t tell you what their descendants were doing several thousand years later, potentially in an entirely different place and probably using an entirely different suite of technologies. Trying to understand what happened in the human past based on the historical and archaeological records is like walking into a room where a bomb has gone off and trying to reconstruct the locations of all the objects before the explosion. You can get some idea, but it’s all very broad strokes. And actually it’s worse than that, because it wasn’t just one explosion, it was lots, and we wouldn’t even know how many if we didn’t have a way of winding the clock back. But these days we do, and it’s ancient DNA.

Sometime between when my grandfather gave me a copy of Luca Cavalli-Sforza's Genes, Peoples, and Languages for my birthday and when you and I decided to read Reich's book together, two big things happened: humans got really, really good at sequencing and reading genomes, and Svante Pääbo’s lab in Leipzig got really, really good at extracting DNA from ancient bones. (How they developed their procedures is actually a really interesting story, which Pääbo retells in his book, but Reich — whose lab uses the same techniques on an industrial scale — gives a good, brief summary of how it works.) Together, these two advances unlocked…well, not quite everything about the deep past, but an absolutely enormous amount. Suddenly we can track the people, not just the pots, and the story is more complicated and fascinating than anything we might have expected. I’ve written elsewhere about some of the aDNA discoveries about human evolution (Neanderthal admixture, the Denisovans, etc.), but I’m even more excited about what ancient DNA reveals about our more recent past. Luckily, that’s what Reich spends most of the book on, with discussion of ancient ghost populations who now exist only in admixture and then chapters on the specific population genetic histories of Europe, India, North America, East Asia, and Africa, each of which contains some discoveries that would make (at least the more sensible) archaeologists and historical linguists go “well, duh” and others that are real surprises.

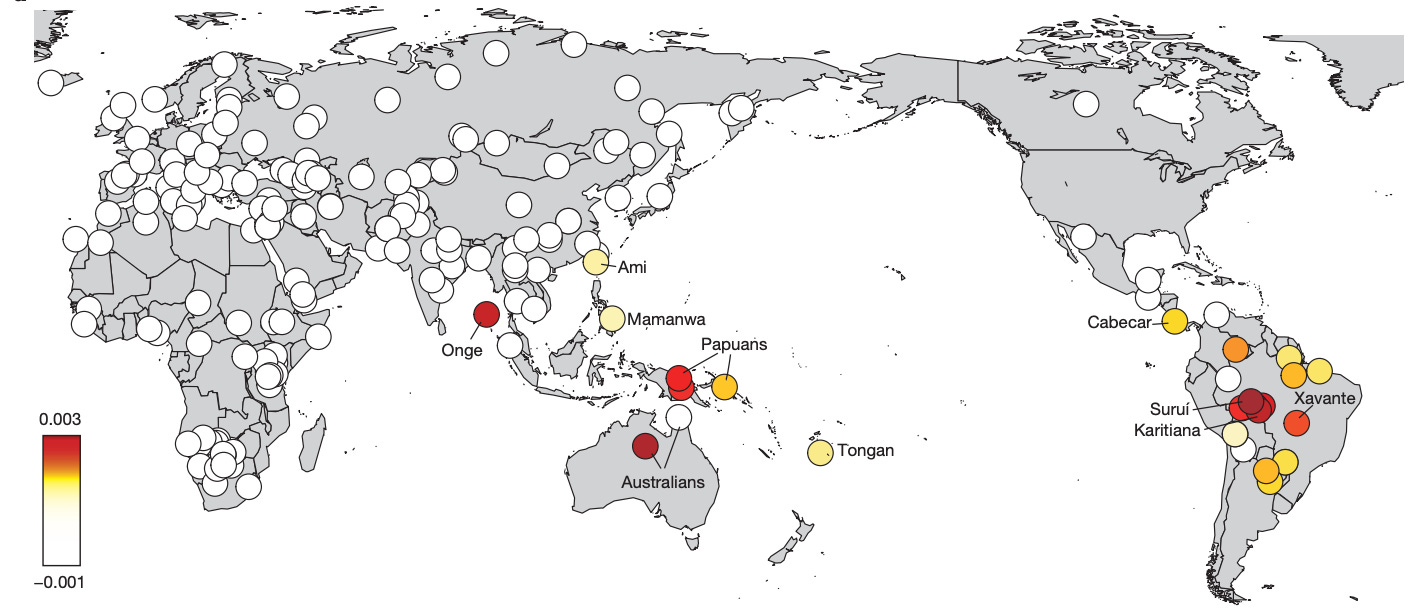

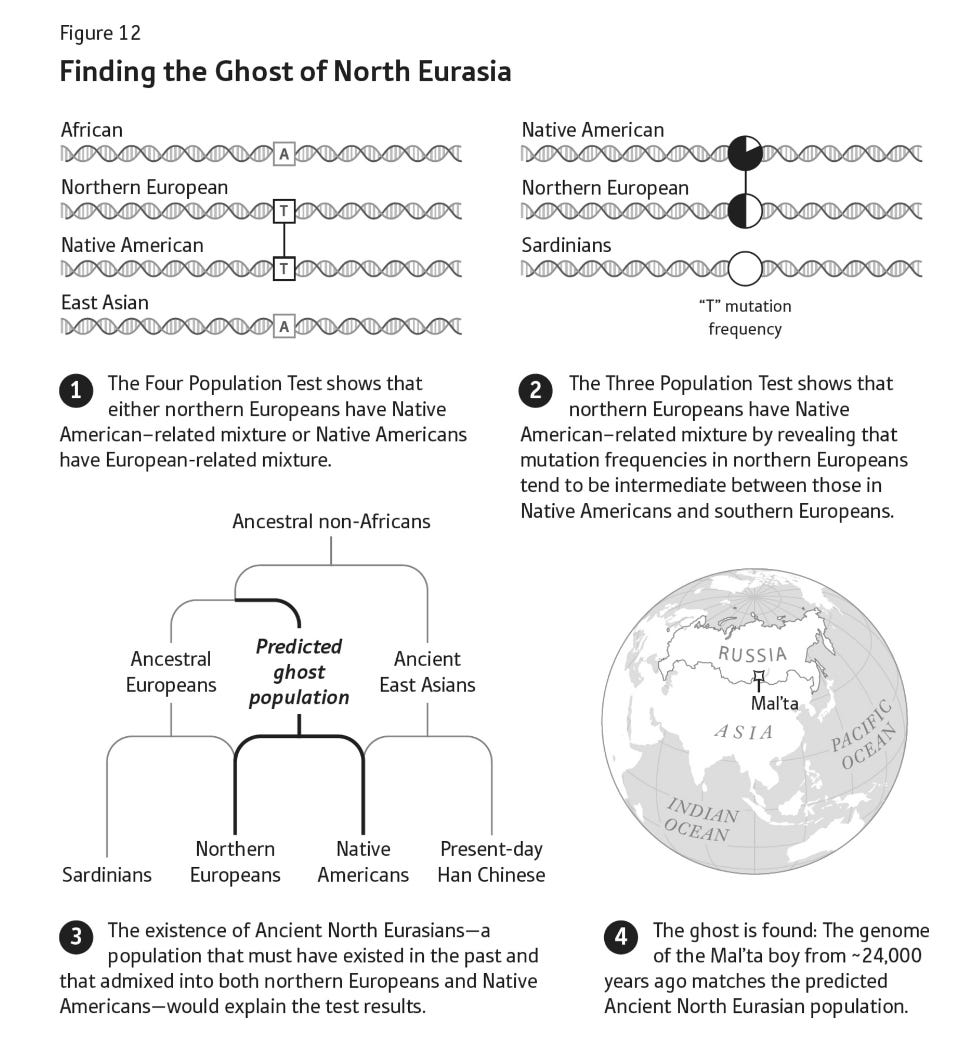

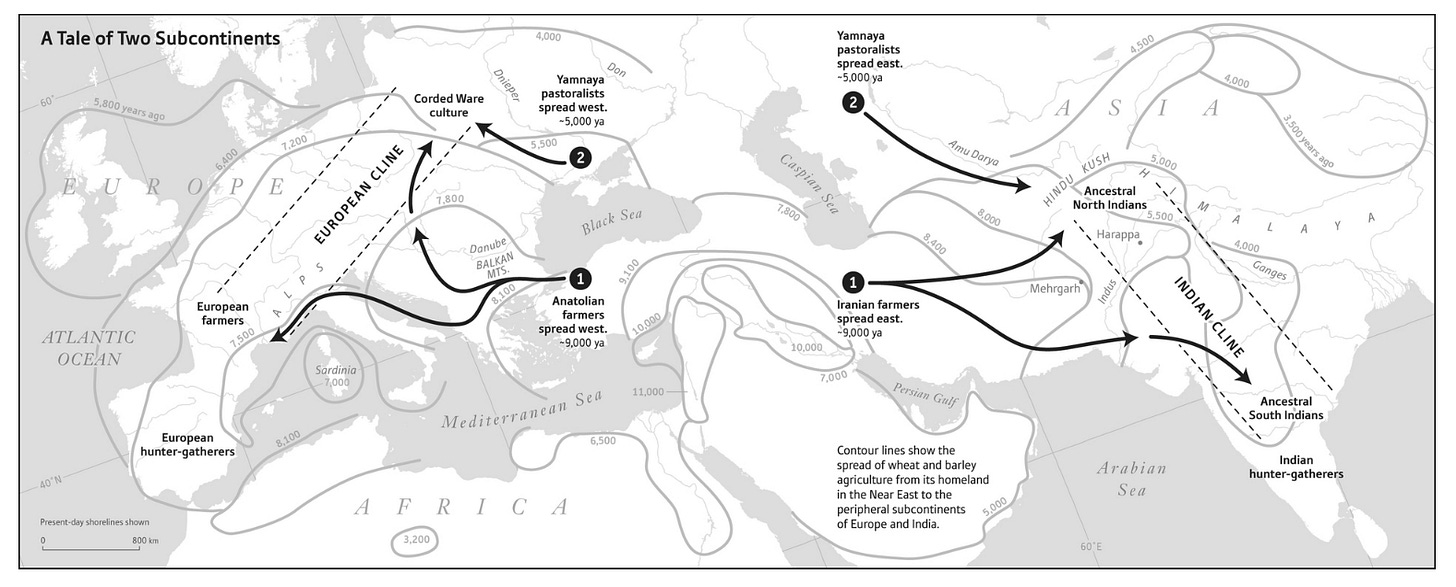

One of the “duh” stories is the final, conclusive identification of the people who brought horses, wagons, and Indo-European languages to Europe with the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic Steppe and their descendants. (David Anthony gives a very good overview of the archaeological case for this is The Wheel, the Horse, and Language, including some very cool experimental archaeology about horse teeth; you have my permission to skim the sections on pots.) My favorite surprising result, though, comes from a little farther north. People usually assume that Native Americans and East Asians share a common ancestor who split from the ancestors of Europeans and Africans before dividing into those two populations, but when Reich’s lab was trying to test the idea they found, to their surprise, that in places where Northern European genomes differ from Africans’, they are closer to Native Americans than to East Asians. Then, using a different set of statistical techniques, they found that Northern European populations were the product of mixture between two groups, one very similar to Sardinians (who are themselves almost-unmixed descendants of the first European farmers) and one that is most similar to Native Americans. They theorized a “ghost” population, which they called the “Ancient North Eurasians,” who had contributed DNA both to the population that would eventually cross the Bering land bridge and to the non-Early European Farmer ancestors of modern Northern Europeans. Several years later, another team sequenced the genome of a boy who died in Siberia 24kya and who was a perfect match for that theorized ghost ANE population.

But we’ve already established that I’m the prehistory nerd in this family; were you as jazzed as I was to read about the discovery of the Ancient North Eurasians?

John: It's true that I don’t get as excited as you about ancient skeletons, but you know I'm always up for the humiliation of a dominant scientific paradigm. I especially like examples where that paradigm in its heyday replaced some much older and unfashionable view that we now know to be correct. It's important to remind people that knowledge gets lost and buried in addition to being discovered.

The wonderful thing about ancient DNA is it gives us an extreme case of this. Basically, the first serious attempt at creating a scientific field of archaeology was done by 19th century Germans, and they looked around and dug some stuff up and concluded that the prehistoric world looked like the world of Conan the Barbarian: lots of “population replacement,” which is a euphemism for genocide and/or systematic slavery and mass rape. This 19th century German theory then became popular with some 20th century Germans who... uh... made the whole thing fall out of fashion by trying to put it into practice.

After those 20th century Germans were squashed, any ideas they were even tangentially associated with them became very unfashionable, and so there was a scientific revolution in archaeology! I'm sure this was just crazy timing, and actually everybody rationally sat down and reexamined the evidence and came to the conclusion that the disgraced theory was wrong (lol, lmao). Whatever the case, the new view was that the prehistoric world was incredibly peaceful, and everybody was peacefully trading with one another, and this thing where sometimes in a geological stratum one kind of house totally disappears and is replaced by a different kind of house is just that everybody decided at once that the other kind of house was cooler. The high-water mark of this revisionist paradigm even had people saying that the Vikings were mostly peaceful traders who sailed around respecting the non-aggression principle.

And then people started sequencing ancient DNA and...it turns out the bad old 19th century Germans were correct about pretty much everything. The genetic record is one of whole peoples frequently disappearing or, even more commonly, all of the men disappearing and other men carrying off the dead men's female relatives. There are some exceptions to this, but by and large the old theory wins.

I used to have a Bulgarian coworker, and I asked him one day how things were going in Bulgaria. He replied in that morose Slavic way with a long, sad disquisition about how the Bulgarian race was in its twilight, their land was being colonized by others, their sons and daughters flying off to strange lands and mixing their blood with that of alien peoples. I felt awkward at this point, and stammered something about that being very sad, at which point he came alive and declared: “it is not sad, it is not special, it is the Way Of The World.” He then launched into a lecture about how the Bulgarians weren't even native to their land, but had been bribed into moving there by the Byzantines who used them as a blunt instrument to exterminate some other unruly tribes that were causing them trouble. “History is all the same,” he concluded, “we invaded and took their land, and now others invade us and take our land, it is the Way Of The World.”

Even a cursory study of history shows that my Bulgarian friend was correct about the Way Of The World. There's a kind of guilty white liberal who believes that European colonization and enslavement of others is some unique historical horror, a view that has now graduated into official state ideology in America. But that belief is just a weird sort of inverted narcissism. I guess pretending white people are uniquely bad at least makes them feel special, but white people are not special. Mass migration, colonization, population replacement, genocide, and slavery are the Way Of The World, and ancient DNA teaches us that it's been the Way Of The World far longer than writing or agriculture have existed. It wasn't civilization that corrupted us, there are no noble savages, “history is all the same,” an infinite history of blood.

Land acknowledgments always struck me as especially funny and stupid: like you really think those people were the first ones there? What about acknowledging the people that they stole it from? Sure enough one of the coolest parts of Reich's book is his recounting the discovery that there were probably unrelated peoples in the Americas before the ancestors of the American Indians arrived here, and that a tiny remnant of them might even remain deep in Amazonia. So: what does it actually mean to be “indigenous?” Is anybody anywhere actually “indigenous?”

Jane: Well, if by indigenous we mean “the minimally admixed descendants of the first humans to live in a place,” we can be pretty confident about the Polynesians, the Icelanders, and the British in Bermuda. Beyond that, probably also those Amazonian populations with substantial Population Y ancestry and some of the speakers of non-Pama–Nyungan languages in northern Australia? The African pygmies and Khoisan speakers of click languages who escaped the Bantu expansion have a decent claim, but given the wealth of hominin fossils in Africa it seems pretty likely that most of their ancestors displaced someone. Certainly many North American groups did; the “skraelings” whom the Norse encountered in Newfoundland were probably the Dorset, who within a few hundred years were completely replaced by the Thule culture, ancestors of the modern Inuit. (Ironically, the people who drove the Norse out of Vinland might have been better off if they’d stayed; they could hardly have done worse.)

But of course this is pedantic nitpicking (my speciality), because legally “indigenous” means “descended from the people who were there before European colonialism”: the Inuit are “indigenous” because they were in Newfoundland and Greenland when Martin Frobisher showed up, regardless of the fact that they had only arrived from western Alaska about five hundred years earlier. Indigineity in practice is not a factual claim, it’s a political one, based on the idea that the movements, mixtures, and wholesale destructions of populations since 1500 are qualitatively different from earlier ones. But the only real difference I see, aside from them being more recent, is that they were often less thorough — in large part because they were more recent. In many parts of the world, the Europeans were encountering dense populations of agriculturalists who had already moved into the area, killed or displaced the hunter-gatherers who lived there, and settled down. For instance, there’s a lot of French and English spoken in sub-Saharan Africa, but it hasn’t displaced the Bantu languages like they displaced the click languages. Spanish has made greater inroads in Central and South America, but there’s still a lot more pre-colonial ancestry among people there than there is pre-Bantu ancestry in Africa. I think these analogies work, because as far as I can tell the colonization of North America and Australia look a lot like the Early European Farmer and Bantu expansions (technologically advanced agriculturalists show up and replace pretty much everyone, genetically and culturally), while the colonization of Central and South America looks more like the Yamnaya expansion into Europe (a bunch of men show up, introduce exciting new disease that destabilizes an agricultural civilization,2 replace the language and heavily influence the culture, but mix with rather than replacing the population).

Some people argue that it makes sense to talk about European colonialism differently than other population expansions because it’s had a unique role in shaping the modern world, but I think that’s historically myopic: the spread of agriculture did far more to change people’s lives, the Yamnaya expansion also had a tremendous impact on the world, and I could go on. And of course the way it’s deployed is pretty disingenuous, because the trendier land acknowledgements become, the more the people being acknowledged start saying, “Well, are you going to give it back?” (Of course they’re not going to give it back.) It comes off as a sort of woke white man’s burden: of course they showed up and killed the people who were already here and took their stuff, but we’re civilized and ought to know better, so only we are blameworthy.

More reasonable, I think, is the idea that (some of) the direct descendants of the winners and losers in this episode of the Way Of The World are still around and still in positions of advantage or disadvantage based on its outcome, so it’s more salient than previous episodes. Even if, a thousand years ago, your ancestors rolled in and destroyed someone else’s culture, it still sucks when some third group shows up and destroys yours. It’s just, you know, a little embarrassing when you’ve spent a few decades couching your post-colonial objections in terms of how mean and unfair it is to do that, and then the aDNA reveals your own population’s past…

Reich gets into this a bit in his chapter on India, where it’s pretty clear that the archaeological and genetic evidence all point to a bunch of Indo-Iranian bros with steppe ancestry and chariots rolling down into the Indus Valley and replacing basically all the Y chromosomes, but his Indian coauthors (who had provided the DNA samples) didn’t want to imply that substantial Indian ancestry came from outside India. (In the end, the paper got written without speculating on the origins of the Ancestral North Indians and merely describing their similarity to other groups with steppe ancestry.) Being autochthonous is clearly very important to many peoples’ identities, in a way that’s hard to wrap your head around as an American or northern European: Americans because blah blah nation of immigrants blah, obviously, but a lot of northern European stories about ethnogenesis (particularly from the French, Germans, and English) draw heavily on historical Germanic tribal migrations and the notion of descent (at least in part) from invading conquerors.

One underlying theme in the book — a theme Reich doesn’t explicitly draw out but which really intrigued me — is the tension between theory and data in our attempts to understand the world. You wrote above about those two paradigms to explain the spread of prehistoric cultures, which the lingo terms “migrationism” (people moved into their neighbors’ territory and took their pots with them) and “diffusionism”3 (people had cool pots and their neighbors copied them), and which archaeologists tended to adopt for reasons that had as much to do with politics and ideology as with the actual facts on (in!) the ground. And you’re right that in most cases where we now have aDNA evidence, the migrationists were correct — in the case of the Yamnaya, most modern migrationists didn’t go nearly far enough — but it’s worth pointing out that all those 19th century Germans who got so excited about looking for the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat were just as driven by ideology as the 21st century Germans who resigned as Reich’s coauthors on a 2015 article where they thought the conclusions were too close to the work of Gustaf Kossinna (d. 1931), whose ideas had been popular under the Nazis. (They didn’t think the conclusions were incorrect, mind you, they just didn’t want to be associated with them.) But on the other hand, you need a theory to tell you where and how to look; you can’t just be a phenomenological petri dish waiting for some datum to hit you. This is sort of the Popperian story of How Science Works, but it’s more complex because there are all kinds of extra-scientific implications to the theories we construct around our data.

The migrationist/diffusionist debate is mostly settled, but it turns out there’s another issue looming where data and theory collide: the more we know about the structure and history of various populations, the more we realize that we should expect to find what Reich calls “substantial average biological differences” between them. A lot of these differences aren’t going to be along axes we think have moral implications — “people with Northern European ancestry are more likely to be tall” or “people with Tibetan ancestry tend to be better at functioning at high altitudes” isn’t a fraught claim. (Plus, it’s not clear that all the differences we’ve observed so far are because one population is uniformly better: many could be explained by greater variation within one population. Are people with West African ancestry overrepresented among sprinters because they’re 0.8 SD better at sprinting, or because the 33% higher genetic diversity among West Africans compared to people without recent African ancestry means you get more really good sprinters and more really bad ones?) But there are a lot of behavioral and cognitive traits where genes obviously play some role, but which we also feel are morally weighty — intelligence is the most obvious example, but impulsivity and the ability to delay gratification are also heritable, and there are probably lots of others. Reich is adorably optimistic about all this, especially for a book written in 2018, and suggests that it shouldn’t be a problem to simultaneously (1) recognize that members of Population A are statistically likely to be better at some thing than members of Population B, and (2) treat members of all populations as individuals and give them opportunities to succeed in all walks of life to the best of their personal abilities, whether the result of genetic predisposition or hard work. And I agree that this is a laudable goal! But for inspiration on how our society can both recognize average differences and enable individual achievement, Reich suggests we turn to our successes in doing this for…sex differences! Womp womp.

John: Wow, way to steer this book review into dangerous territory, dear. Let me answer by way of a story: I had an acquaintance in college who was a dedicated leftist and who also believed in substantial group differences in average IQ.4 One day she was fretting at me that advances in data science, genetics, etc. were going to make this unpalatable reality impossible to ignore, with detrimental consequences for both racial justice and social harmony. Facts and logic were going to explode the noble lie, oh no!

Obviously I had to physically restrain myself from laughing at her. Assuming for the sake of argument that such differences exist and are easily measurable, only somebody totally autistic would think that mere scientific evidence for them would cause them to be acknowledged.5 Just look at all the ridiculous “sky is green” type beliefs that society already successfully forces everybody to internalize. You mentioned biological and cognitive differences between men and women, which are far more obvious and noticeable than those between populations, but which we successfully force everybody to pretend do not exist. And that’s far from the silliest thing everybody pretends to believe, in our society or in others.

Put it another way: there is no such thing as a secular society, every country has a state religion, and you won't get very far opposing it. Were there people in Tenochtitlan who secretly believed that blood pouring down the sides of the great step pyramid day and night wasn’t actually necessary to placate the gods? Yeah probably, but if any of them had tried to point that out, they would have been laughed at (and sacrificed). Were there people in the Soviet Union who privately doubted whether dialectical materialism was the true engine of history? Probably, yes, but everybody besides Leonid Kantorovich was smart enough not to mention it.

What are the religious precepts on which our society is founded? There are a few, but a belief in absolute racial equality is clearly one of them, and that view is now enshrined in the “real” constitution (civil rights caselaw and its downstream effects on corporate HR). Anything which contradicts that precept is just a total nonstarter. If a few nerds somewhere found irrefutable evidence of important differences between groups, they would quietly hide it, and if some among them were like Reich too autistic or principled to do that, they would be ignored, shouted down, or persecuted. Possibly this would even be a good thing — every society needs its orthodoxies, and sometimes those who corrupt the youth need to drink the hemlock.

We’ve gotten far afield, though. As an inveterate shape-rotator, my favorite part of the book was Reich's description of the statistical and mathematical techniques that can be used to determine when population bottlenecks occurred, how recently two populations shared a common ancestor, and when various mixing events occurred. What did you think of all this? From your point of view was it impenetrable or well-explained?

Jane: Oh, it was great. (Also, excuse you, I may be a wordcel but I try harder.) I think Reich hits exactly the right balance for this kind of “intelligent layperson” book: he’s mostly interested in telling you what they’ve found, and explains only as much as you need to know in order to understand the results. (And the statistical approaches are really very clever!) I’ve read a lot of books on aDNA lately, and there are basically two models that work for me: either you have to tell the whole story, dead ends and frustrations and personal conflicts and all, or you have to focus on what you’ve found. A lot of authors try to eke out this awkward middle ground, where they spend two pages explaining how next-generation sequencing works and my eyes glaze over, then they dive right into their results. I understand the impulse — it seems unsatisfying to say “we did it using science” — but honestly it all seems like magic unless you start waaaaay back down the chain of events and give greater detail than really makes sense for many books. Put it in an appendix, my man! Svante Pääbo’s book (which I mentioned above) is sort of the flip side of Reich’s, much more interested in the story of how these discoveries were made than in what they were, but it really worked for me in a way the middle ground books didn’t. If you’re going to start telling me about pyrosequencing I need all that context to make me, how do you say, care.

Then again, Reich has an advantage because his innovations are easier to boil down; I grok math and statistics a lot better than biology. (Probably this comes from mumbledy-mumble years of marriage to you; goodness knows it’s not from high school or college.) And maybe that’s the coolest thing about this book: that they’ve been able to turn bags of mostly water into math, and then use that math to tell us about history. We’re so used to carving in reality into disciplines that we sometimes lose sight of the fact that these are all just different angles for approaching truth. aDNA lets us put it back together again: here we have archaeology and historical linguistics and biology and math working together (Reich’s closest collaborator is a mathematician who worked for the British equivalent of the NSA and then as a quant at a hedge fund) to tell us about our ancestors. And why do we care? Well partly because knowing about the past helps us understand how the world got the way it is, but more importantly because knowing about the past helps us understand how the world could be. What are the options? What is the possibility space for humanity? What’s fundamental to our nature and what’s merely contingent? Some of the answers that have turned up aren’t very cheerful — killing people and taking their stuff seems to be, uh, pretty ingrained there, not that we should have needed aDNA to tell us that — but they all matter.

John: There's a famous video in which Richard Feynman is asked by a BBC journalist if he can explain magnetism to him, and Feynman pauses for a moment and says “no.” The journalist is totally incredulous, and demands to know what Feynman means by that, and the great scientist tells him that he knows so little of the basics, and magnetism is so deep and so tricky,6 that it would be impossible to explain much of anything without either misleading him or giving him a false understanding.

I’ve always thought that nearly all pop science books fall into one version or another of this trap. Either they abandon all attempts at explaining the difficult concept in simple terms, or they simplify and elide so much as to become actively misleading.7 I call the latter horn of the dilemma “string theory is like a taco”-syndrome, and it’s by far the more common failure case. This is because undersimplification makes your audience feel dumb, while oversimplification makes them feel smart, so you sell a lot more books by oversimplifying. Unfortunately the effects on the audience of oversimplification are far more dangerous and insidious. After reading something impenetrable, you at least still know that you don’t really understand it, so there’s still a chance for you to go on and learn it some other way. Reading an oversimplified explanation, however, can fool you into thinking that you now grasp the concept, when in reality all you've grasped is a lossy analogy that will lead you astray.

All of which is to say I think it's pretty impressive how well Reich does at diving into some of the real statistical meat of his techniques while still making them comprehensible to a smart layman. He has the gift that the greatest scientific expositors possess of being able to communicate in simple terms what it is that makes a problem hard, and then also giving you the broad strokes of an elegant solution to that hard problem. He doesn’t pretend that he hasn’t left anything out, instead he points out exactly where he’s glossed over details, so that you can go back and look them up if you want. This doesn't sound all that impressive, but it's actually really freaking hard to pull off, especially in a field that’s new and hence hasn’t been reformulated and recondensed a hundred times until it's turned into a crystalline version of itself.

Okay, what was your favorite interesting genetic fact that this book taught you about a contemporary population? Mine was definitely that the various Indian jatis are as genetically distinct from one another as the Ashkenazi Jews are from everybody else. Not one group, but hundreds and hundreds of groups, all living in close proximity to each other, have gone millennia with incredibly minimal genetic mixing. How is that possible? It makes me take some of the assertions made by classical Indian texts a little bit more seriously.

Jane: The bit that really blew my mind wasn’t about any group in particular (though you know me, anything about the proto-Indo-Europeans is going to get me excited), but comes right in the first chapter when Reich is explaining how genetic inheritance works. It goes sort of like this: you have two copies of each of your chromosomes, one from your mother and one from your father, but your gametes have only one copy of each chromosome, which is produced by splicing together bits from both of yours. One gamete might have, say, the first two-thirds of chromosome 2 from your mother and the rest from your father, while another might have the first quarter from your father, the middle half from your mother, and the last bit from your father again. On average, there are 71 new splices in each generation (across all 23 chromosomes in your germ cells), which is to say that you could imagine each set of chromosomes you inherited from each of your parents being chopped into 71(-ish) pieces and then having one of those pieces picked for the new gamete. But while the number of genetic splices increases linearly, your number of genealogical ancestors doubles with every generation.8 At the beginning this doesn't really matter: you could imagine your four grandparents’ gametes chopped up into 300-odd pieces and randomly assorted into you, and you’d have approximately a quarter of your genome from each. But you rapidly reach the point where you have more ancestors than you have stretches of ancestral DNA — go back ten generations and there’s only about a 50% chance you have genes from any given ancestor. At fifteen generations, the chance drops to 3%. In short, most of your genealogical ancestors did not contribute any of your DNA.

In one sense this seemed sort of depressing: we say our children make us human, our family is “unrolling its generations,” &c. &c., and then it turns out that before long we’re not even part of them? But then I thought about it some more and decided it’s really quite beautiful. We sometimes like to talk about our family as “building a cathedral” — it’s a work for the ages, you and I will never see in its entirety, here we are doing one little part but the finished project is something so far beyond the human scale in time and space that it’s hard to wrap our heads around the immensity of it, sometimes people fall off scaffolding, and so forth. But it’s like a cathedral in this way too: no one knows the names of the men who laid the stones of Notre-Dame or blew the glass for the rose windows of Chartres, just like no one has the genes (or knows the names!) of all their thousands of fifteen-greats grandmothers. But nevertheless the things they built — the cathedrals, the families — still stand: being remembered was never the point, building something was. And the things they built have so far outlasted them that their very signatures have been worn away by time. I hope ours does too.

Happy anniversary, darling. ❤️

That's the latest plausible date for the arrival of full “behavioral modernity” in Africa, though our genus goes back about two million years, tool use probably three million, and I think there's a good case that Homo was meaningfully “us” by 500kya. (That's “thousand years ago” in “I talk about deep history so much I need an acronym,” fyi.)

aDNA works for microbes too, and it looks like Y. pestis, the plague, came from the steppe with the Yamnaya. It didn’t yet have the mutation that causes buboes, but the pneumonic version of the disease is plenty deadly, especially to the Early European Farmers who didn’t have any protection against it. In fact, as far as we can tell, in all of human history there have only been four unique introductions of plague from its natural reservoirs in the Central Asian steppe: the one that came with or slightly preceded the Yamnaya expansion around 5kya, the Plague of Justinian, the Black Death, and an outbreak that began in Yunnan in 1855. The waves of plague that wracked Europe throughout the medieval and early modern periods were just new pulses of the strain that had caused Black Death. Johannes Krause gets into this a bit in his A Short History of Humanity, which I didn’t actually care for because his treatment of historic pandemics and migrations is so heavily inflected with Current Year concerns, but I haven’t found a better treatment in a book so it’s worth checking it out from the library if you’re interested.

I cheated with that “pots not people” line in my earlier email; it usually gets (got?) trotted out not as a bit of epistemological modesty about what the archaeological record is capable of showing, but as a claim that the only movements involved were those of pots, not of people.

Not to get all “Dems are the real racists,” but anecdotally this view does seem slightly more prevalent among my left-wing friends than my right-wing friends, though that seems to currently be changing.

Somebody totally autistic or somebody who had already drunk the kool-aid on literally every other ridiculous official viewpoint imposed by our society. In her case it was probably the latter. As I said she was a leftist, and women in general are much less likely to be autistic but much more likely to value social conformity.

It always bothered me when people ragged on Insane Clown Posse for expressing humility and awe at magnets. In fact their attitude is exactly the appropriate one. Back when ICP were in the news more often, I made a minor hobby of demanding that anybody who made fun of them explain magnets scientifically to me on the spot. Nobody ever succeeded.

And sometimes, remarkably, a pop science book manages to make both mistakes at the same time. I'm reminded of Edward Frenkel's horrible book Love & Math, which is full of passages like: “Think of the Hitchin fibration as a box of donuts, except that there are donuts attached not only to a grid of points in the base of the carton box, but to all points in the base. So we have infinitely many donuts — Homer Simpson would sure love that! It turns out that the mirror dual Hitchin moduli space, the one associated to the Langlands dual group, is also a donut topic/fibration over the same base. Donuts. Is there anything they can't do?”

At least until you accumulate enough ancestors that they start appearing in more than one place in your family tree, which happens sooner or later even if you don’t marry your cousin.

> He replied in that morose Slavic way with a long, sad disquisition about how the Bulgarian race was in its twilight, their land was being colonized by others, their sons and daughters flying off to strange lands and mixing their blood with that of alien peoples... He then launched into a lecture about how the Bulgarians weren't even native to their land

OK! I'd have a drink with that guy.

I miss having Slavic friends.

This is so good. Maybe it’s that I’m reading a lot of slop lately but I’m a little surprised at how much I learned and how much I enjoyed reading this. Thank you.