REVIEW: The Art of Not Being Governed, by James C. Scott

The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, by James C. Scott (Yale University Press, 2010).

Like many great thinkers, James C. Scott’s ideas seem totally obvious once you’ve heard them. But with Scott this problem is exacerbated by the fact that every single person on the internet has only read one of his books. Let’s read a different book.

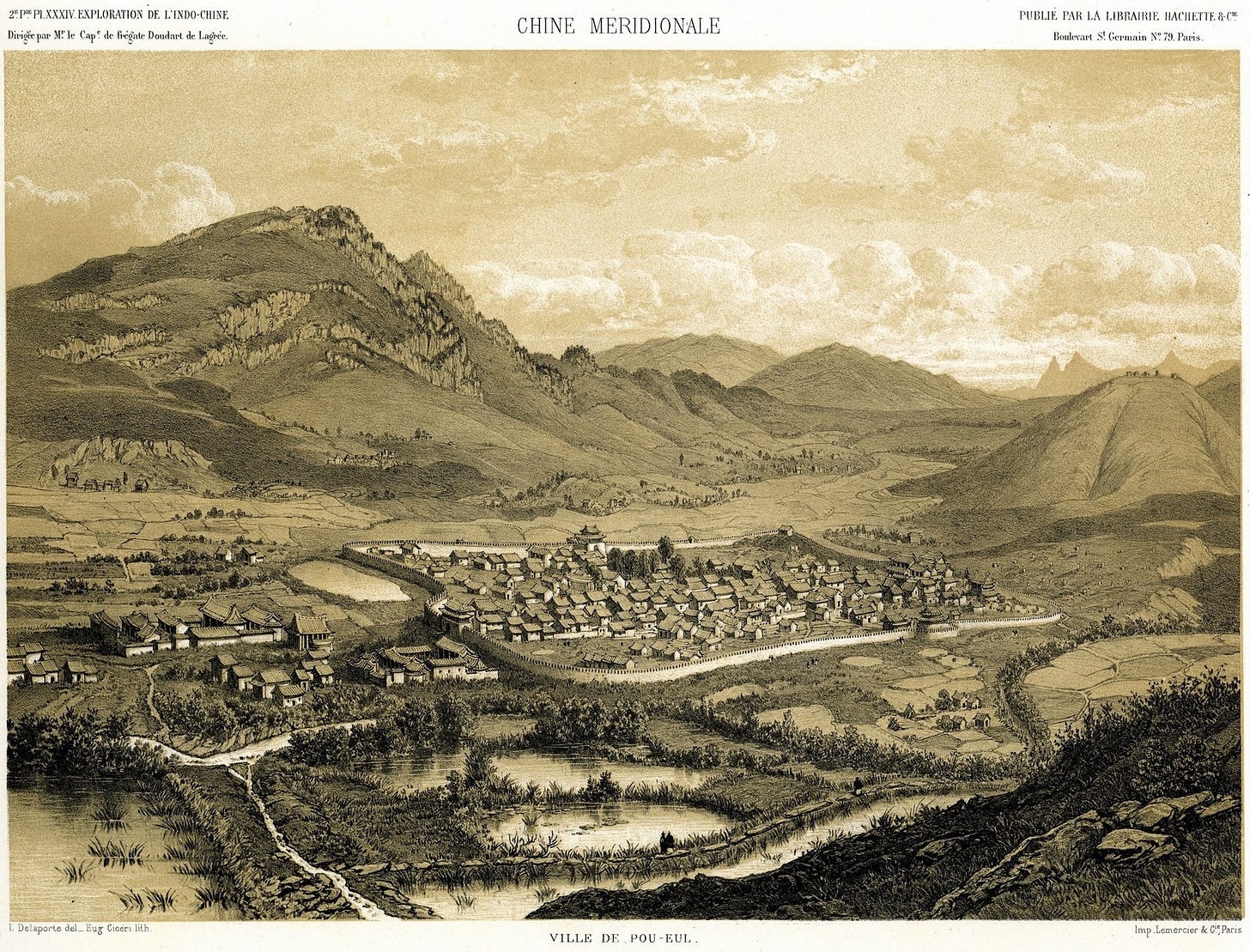

There’s a clichéd history of civilization which goes something like: once upon a time all human beings lived in wandering hunter-gatherer bands where everybody was directly involved in food production. Then while sojourning through a fertile river valley, some of these groups discovered agriculture. The relative predictability and reliability of farming, coupled with the much higher caloric yield per hour of labor,1 made it possible to support a denser population, and for only a portion of it to be directly involved in food production. The rest of them could become soldiers, artisans, priests, and scribes. They could develop technology, pass on their knowledge through writing, and develop complex systems of taxation, bureaucracy, and forced labour. Along the way, they made picturesque little walled farming villages like the one below.

This is not their story. Instead it’s the story of the people who live in the hills behind that village. Without knowing anything at all about the place that picture depicts, you can probably tell me a lot about the people in those hills. Hill people are hill people, the world over. What are the odds that they’re clannish? Xenophobic? Backwards! Unusual family structures. Economically immiserated (probably due to their own paranoia and indolence). Deviant in their religious, commercial, and sexual practices. Illiterate, or at best poorly-read. They also probably talk funny. Basically they’re barbarians, but not the impressive kind who ride out of the steppe to massacre and enslave the soft city-dwellers. No, something more like living fossils — our ancestors were once like that, but then they got with the program. Well if they could do it, why don’t those hill dwellers move down here too, like normal people?2 They’re up to no good up there.

That’s certainly been the traditional view from the valleys, and there’s some truth to it, but there’s one important detail that we valley-dwellers get wrong. Far from being aboriginal holdovers of some previous phase of humanity, it’s relatively easy to determine from genetic, linguistic, and archaeological evidence that the hill people are largely descended from… the valley people!3 But… that would mean that there are people who look around at our beautiful civilization and reject its fruits — you know, art, technology, fusion cuisine, and uh… taxation, conscription, epidemic disease, corvée labour… How dare they!

You would never know it from reading the reports of the valley-bureaucrats, but the great agricultural civilizations of classical antiquity were in a near-constant state of panic over people wandering away from their farms and becoming barbarians.4 There are estimates that over the course of the empire something like twenty-five percent of the inhabitants of Roman border provinces quietly slipped across the limes for the proud life of the savage. In Ancient China, the movement was more cyclical — in times of war, or epidemic, or famine, entire villages might give up rice agriculture and vanish into the hills. Then, when the situation had stabilized, the human tide would reverse, and the hills would disgorge barbarians eager to be Sinicized (or really re-Sinicized, as their parents and grandparents had been). In both these cases and more, the boundary between “civilized” and “savage” was a great deal more porous, and the flow a great deal more bi-directional than we might realize. Like a single substance in two phases, now boiling, now condensing, changing back and forth in response to changes in the temperature.

So why then is it that hill people5 the world over have so much in common? Scott argues pretty convincingly that something like convergent cultural evolution for ungovernability is at work — that is, the qualities we stereotypically associate with backwards and barbarous peoples are precisely the traits that make one difficult to administer and tax. Some examples of this are very obvious to see — for instance physical dispersal in difficult terrain makes it harder to be surveilled, measured, or conscripted. Scott also talks a lot about the crops that hill people like to grow, and how the world over they tend to be either crops that are amenable to swiddening and don’t require irrigation, or things like tubers that mature underground and can be harvested at irregular times. Both patterns make it easy to lie about how much food you’ve planted and where, hence difficult for others to tax or control you.

What about illiteracy? Scott finds that many hill people around the world have oral legends about how they once had writing, but no longer do. Of course this is exactly what we would expect if, contrary to the usual story, the hill people are not the ancestors of the valley people, but their descendants. Yet the question remains, why give up writing? Scott posits several benefits of illiteracy: one is just that the inability to write removes any temptation to keep written records of anything, and written records are the kind of thing that can be used against you by a tax collector or an army recruiter.

But more fundamentally, a reliance on oral history and genealogy and legend is powerful precisely because these things are mutable and can be changed according to political convenience. Anybody who’s read ancient Chinese accounts of the steppe peoples or Roman discussions of Germanic barbarians has probably recoiled from the confusing profusion of tribes, peoples, and nations; the same ethnonyms popping in and out of existence over a vast area, or referring to a band of a few hundred one year and a nation of millions a decade later. Scott argues that the reason we see this is that the very notion of stable ethnic identity is a fundamentally “valley” conceit. Out in the hills or on the far wild plains, people exist in more of a quantum superposition of identities, and the nonsensical patterns you see in the histories come from imperial ethnographers feverishly making classical measurements in a double-slit experiment and trying to jam the results into a sensible form.

Naturally this all made me think of 4chan. The swirling chaos that dominates the more subaltern corners of online bears an eerie resemblance to the mutability of identity that Scott chronicles as a form of resistance to domination. If the channers and the Twitter anons seem a little barbaric (in the less descriptive, more judgmental sense of the word), well, they are, but hill people frequently are too. “Self-barbarization” can be be a very effective conscious or unconscious strategy of resistance while simultaneously making a group unpleasant to be around (in fact these things are linked).

The digital barbarians have for now made themselves illegible to the hyper-surveillance, algorithmic discipline, and intrusive analytics that loom like the hundred-eyed Argos over all online interactions. In fact, insofar as a key technique of the cyber-panopticon is the construction of predictive models of user behavior, to be unpredictable is an important component of being ungovernable. The other option is to hide.

Hiding is a strategy that some people attempt offline as well, either by building a compound in the woods or by adopting protective coloration and hiding in plain sight. But as the bots grow ever more omniscient, hiding gets more expensive and less effective. Another classic barbarian-inspired strategy is to maximize mobility, and indeed contemporary economic and technological conditions seem ripe for a renaissance of nomadism. But the trouble with always being ready to pack your bags is it makes it hard for anybody to count on you.6 Is there anything that can be done for those of us who want to live marginally more barbarically, but still sip lattes and put down roots? Yes, because the ultimate lesson of Scott’s book is that barbarism is really more of a state of mind that can be practiced anywhere. Three brief examples of ways to increase your Barbarism Quotient (BQ), suitable for the discerning urban barbarian:

Keep your identity small. Paul Graham once said this, but we can go much further. An expansive identity implies its contrapositive: a similarly expansive set of ideas, behaviors, and lifestyles which we cannot adopt without incurring psychic damage. This limits our space for action, and makes us easier for the machines to predict and for the man to control. Better far to figure out what you really care about, figure out what the real red lines are, and convert everything else from a non-negotiable into a piece of the optimization frontier. The ethnic and cultural mutability of barbarous peoples is an example of this kind of suppleness, but there are other sorts of mutability that can be useful too.

The great Boston T. Party once declared: “it’s better to have $1,000 of ammunition in your garage than $1,000 in your bank account; but it’s even better to have only $100 of ammunition in your garage and $900 of practice.” A lot of would-be modern barbarians daydream about burying gold bars in the ground or sewing them into the lining of their clothes (like the barbarians of yore hiding their tubers in the ground), but Mr. Party’s insight generalizes well here. Physical gold is admittedly a less legible form of wealth than T-bills or CBDC; but skills, knowledge, and relationships are even harder to seize than bullion, and even easier to transport across borders. The wise barbarian judiciously transmutes a fixed percentage of his financial capital into human capital. Nothing improves your ultimate BATNA like having friends or being useful.

Barbarians have a deserved reputation for not taking too kindly to strangers, but this xenophobia and clannishness is tactical. For the hill dweller, most strangers are in one way or another the representatives of hostile alien entities that are out to conscript, tax, and subjugate. The situation for we cosmopolitan, urban, dare I say urbane barbarians is a little bit different. We’ve already reached an accommodation with centralized despotic states, having found the advantages they offer to be worth the tradeoffs. Be that as it may, states have a tendency to try to unilaterally change the terms of the deal. To protect ourselves from this form of encroachment, the correct attitude is not xenophobia, but rather paranoia. The toolkit of modern states is to direct all our enthusiasm towards the Current Thing whilst deadening our senses towards everything else. “We had no idea it could get this bad” is a recurring theme in testimonies given by survivors of oppression and genocide, to which a family culture of “they really are out to get us” is a salutary corrective. Every pinprick ought to raise an alarm, because it could be the prick that precedes the onset of anesthesia. Finally, the cultured barbarian remembers that states are not the only hostile, alien entities waiting for us in the night with drooling jaws.

I could come up with a dozen more such practices, inspired by the hill people Scott documents, and ready for incorporation into the family culture you’re creating. But barbarism is a state of mind, and reflecting on how to keep yourself distinct and aloof from the fat, decadent agriculturalists is part of it. So read this book, and then begin carving out your cultural mountain fastness or your ideological swamp hideout. The barbarians are within the gates, they live among us, and we welcome you to join our ranks.

Scott has yet another book about how this important detail of the stock story is totally false. In Scott’s telling, early agriculture produced fewer calories per hour of work than hunting and foraging. The entire increase in social complexity associated with primitive agriculture came not from a food surplus, but from the fact that it was easier to measure how much food everybody was producing and confiscate a portion of it.

Maybe then one of their descendants can go to Yale Law School and write a book about it.

Next time you’re driving through Montana, try to count how many people are transplants from New York or California.

Once you know this fact, you can go back and read those classical texts esoterically, and nervous panic over people defecting from civilization is practically all you will see.

I’ve used “hill people” throughout this review as a synecdoche for groups that have rejected a life-pattern involving settled agriculture and tax-paying, but as Scott points out there are many kind of terrain unsuitable or difficult for state administration. Marshes have historically been another magnet for those rejecting polite society, as have deserts and open plains.

Unless, that is, you all move together. If somebody wants to pitch me on peripatetic cyber-gypsy life, I am all ears.

This is interesting, & given the mention of marshes, I'd love to read Scott on the Maroons & similar groups. I will say, though, that "paranoia" is both a) very easy to manipulate, and b) inimical to the compromises that make neighborhood possible. Like, the more people view every pinprick as a crisis, the more every local dispute becomes an existential threat, and soon you have people throwing bricks through windows of places that host drag brunches, etc.

Lol I'll also say that praising righteous paranoia seems likely to feed the thing where people convince themselves that they're actually a targeted minority, so anything they do to other people is just self-defense.... There's an inherent conflict, maybe, between taking the "barbarian" self-protective viewpoint and continuing to try to live in community with that motley crew known as "the neighbors."

Cory Doctorow channels Robert Heinlein (and Ursula LeGuin) in a novel about exactly this.

https://craphound.com/category/walkaway/