REVIEW: The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian, by Robert E. Howard

The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian: The Original Adventures of the Greatest Sword and Sorcery Hero of All Time!, Robert E. Howard (ed. Patrice Louinet, Del Ray, 2003).

Know, oh prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars — Nemedia, Ophir, Brythunia, Hyperborea, Zamora with its dark-haired women and towers of spider-haunted mystery, Zingara with its chivalry, Koth that bordered on the pastoral lands of Shem, Stygia with its shadow-guarded tombs, Hyrkania whose riders wore steel and silk and gold. But the proudest kingdom of the world was Aquilonia, reigning supreme in the dreaming west. Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.

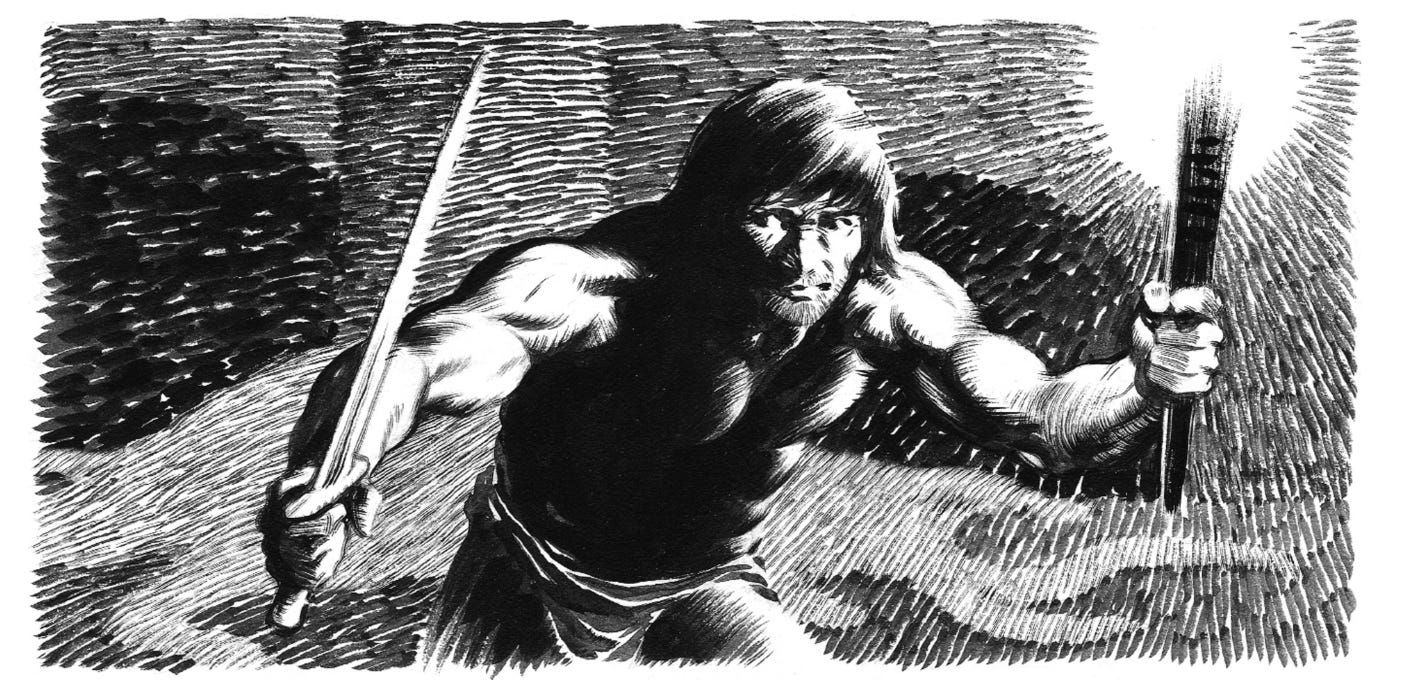

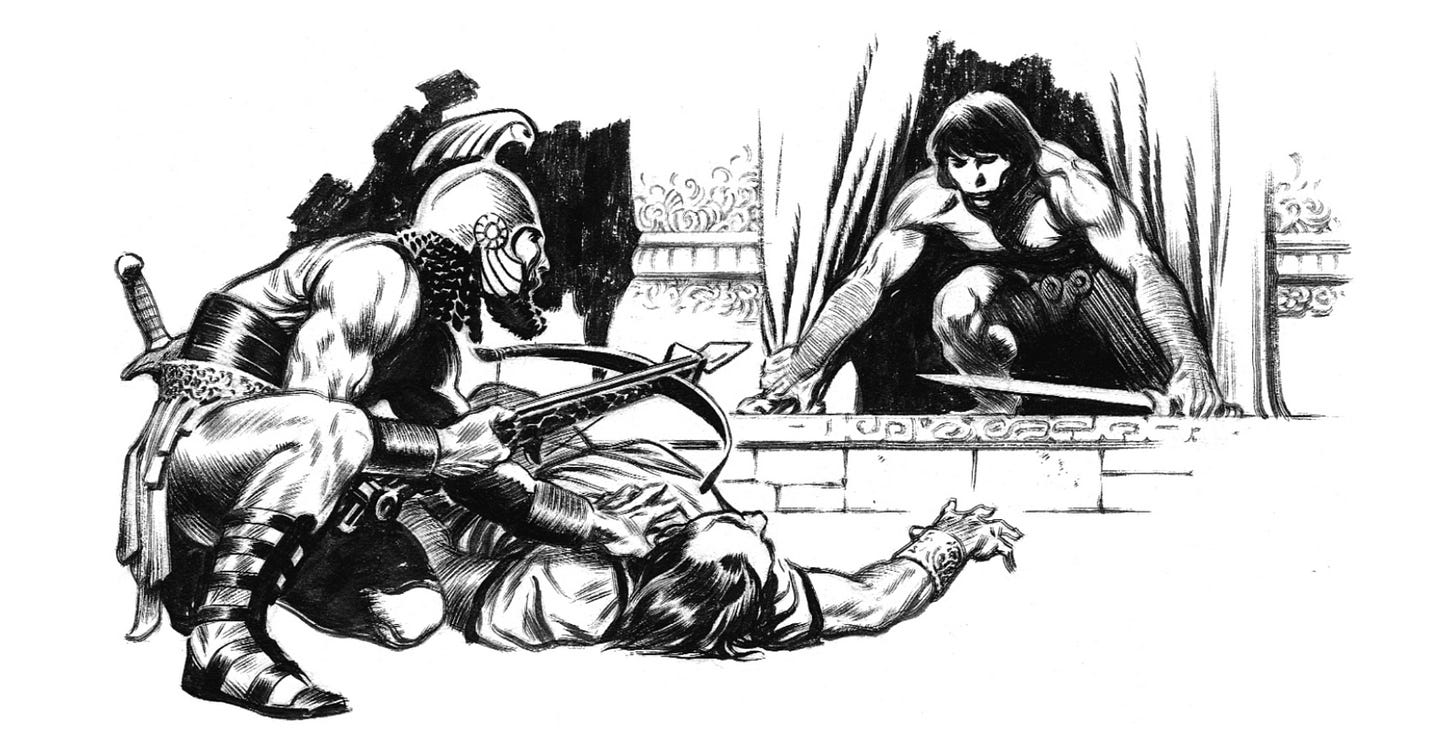

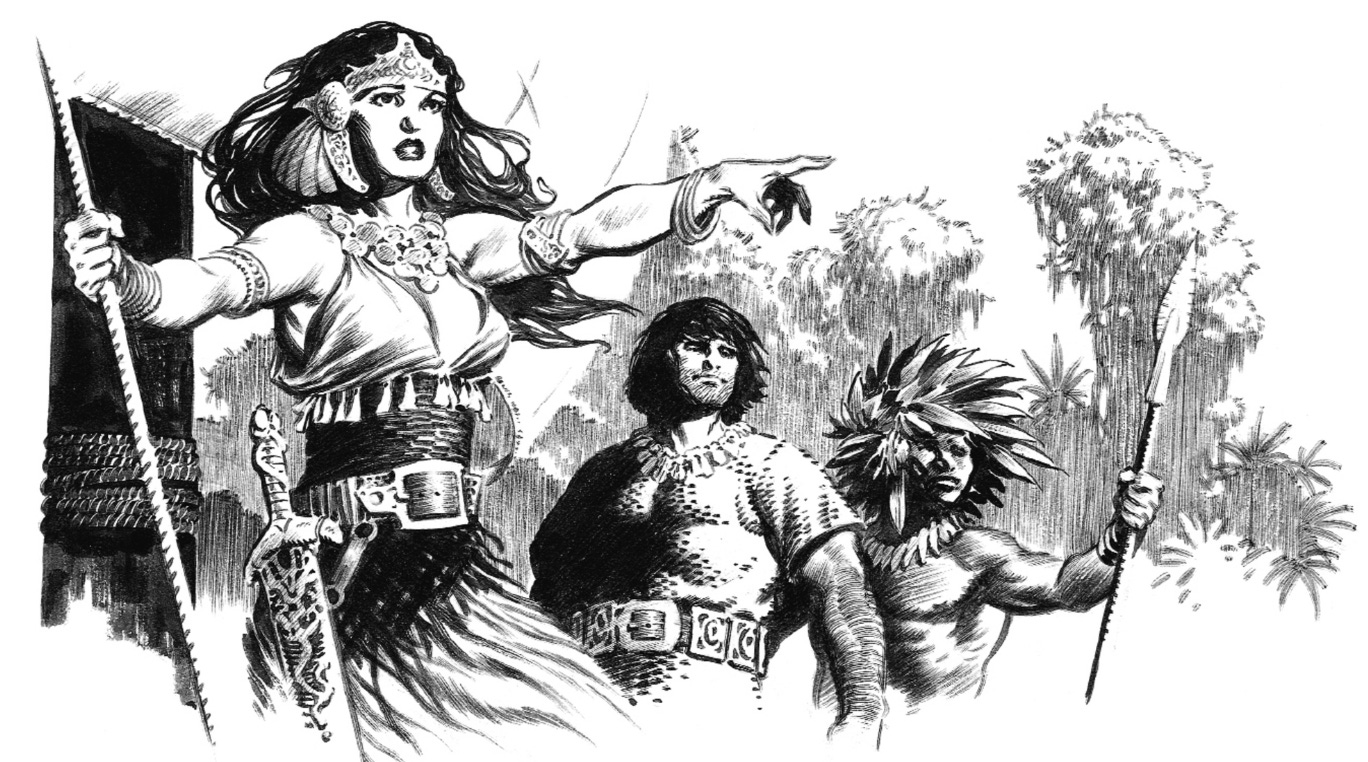

Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories are everything I have ever wanted in fantasy literature — decadent cities bowed under the weight of the ages, wicked sorcerers, gushing arterial blood, lurking antediluvian horrors, red-handed buccaneers, strange magics that have slumbered beneath the sands for untold centuries, glorious cavalry charges into the teeth of death, arcane jewels the size of ostrich eggs, monstrous ape-like demons with slavering jaws, captive princesses, steely thews — and this is the way to read them. For years they were only available in heavily-edited versions, interspersed with “posthumous collaborations,”1 and, worst of all, presented in chronological order (has Narnia taught us nothing?). These editions, though — there are two more volumes — give us Howard’s texts, in the order Howard wrote them, and beautifully illustrated.2 They’re a great pleasure to read, and you should, so I promise not to spoil any major plot points.

Howard got his professional start with boxing stories, but his great authorial love was historical fiction. “There is no literary work, to me, half as zestful as rewriting history in the guise of fiction,” he wrote in 1933. “I wish was I able to devote the rest of my life to that kind of work.” He published stories set during the Crusades (see, for example, Hawks of Outremer, which has some notable similarities to his later work on Conan) and the eras of Mongol and Islamic conquest, and failed to sell tales of ancient Irish warriors. Unfortunately, the markets were slim (more or less only Oriental Stories, which only ran for four year) and the demands of research high: “I could never make a living writing such things, though,” he went on. “[I]t takes me so long to complete one. I try to write as true to the actual facts as possible, at least, I try to commit as few errors as possible. I like to have my background and setting as accurate and realistic as I can…” In his Hyborian Age, the setting for his Conan stories, Howard hit upon an ingenious solution: take the coolest parts of history, file off the serial numbers, and do with them as you will. As a bonus, it means you can combine eras and civilizations that could never have coexisted (or, indeed, existed at all) in real history: the Hyborian Age has 13th century France (or its imagined version of Charlemagne and his Paladins) in the streaming banners of Aquilonia, the Old Kingdom of Egypt in the necromantic rituals of Stygia, warring Assyrian city-states in the lands of Koth, the hill tribesmen of Afghulistan and the tent-dwelling Shemite nomads and the wild pillaging Picts, all immediately recognizable. Howard paints in broadest of strokes, with none of the specifics that would obsess, say, me — there’s no fussing about why classical Greece is next door to the Timurids or why you have the Bronze Age one place and the Middle Ages elsewhere — but it works. Here’s a sweeping picture of rumor spreading across his world in Black Colossus:

Rumors drifted up through the meadowlands, into the cities of the Hyborians. The word ran along the caravans, the long camel-trains plodding through the sands, herded by lean hawk-eyed men in white kaftans. It was passed on by the hook-nosed herdsmen of the grasslands, from the dwellers in tents to the dwellers in the squat stone cities where kings with curled blue-black beards worshipped round-bellied gods with curious rites. The word passed up through the fringe of hills where gaunt tribesmen took toll of the caravans. The rumors came into the fertile uplands where stately cities rose above blue lakes and rivers: the rumors marched along the broad white roads thronged with ox-wains, with lowing herds, with rich merchants, knights in steel, archers and priests.

You know immediately what he’s gesturing at with all these peoples and places. H.P. Lovecraft, Howard’s friend and frequent correspondent, complained about his “incurable tendancy to devise names too closely resembling actual names,” but that was precisely the point. Why waste pages establishing the culture and character of an imaginary people with no emotional valence to anyone but the author when you can simply call a real people to mind in a few choice words? We already have a wealth of associations and baggage with the real world; it just makes sense to use them when you can. This is true on the small scale — as game designer and writer Kenneth Hite points out, your reader will have a much more powerful reaction to the shocking revelation that the queen is a vampire if it’s Elizabeth I rather than Lots’apostrae’fiis VII, to whom they were introduced three pages ago3 — but it’s even more useful when your fictional world has a wide scope. And indeed, Howard’s strategy works so well that it’s been copied by a great deal of subsequent fantasy literature: A Song of Ice and Fire is full of it, as is the world of Warhammer Fantasy. Even Tolkien, widely considered the master of secondary world fiction, works best for me when he draws most directly on the real world: on a recent re-read of Lord of the Rings, I cheered for the Rohirrim but had trouble caring about the Dúnedain and the line of Elendil until I started mentally substituting “Atlantis” for Númenor.

If you’ve only seen the movie (and you have seen the movie, haven’t you?), you may not recognize the Conan of these stories. The film captures the mood of Howard’s world wonderfully, and it shares his gift for implying a wealth of worldbuilding detail in a few words, but Schwarzenegger’s Conan has something of the wide-eyed ingenu about him for all his bulging muscles. For most of the film, he is fundamentally acted upon in a way that Howard’s hero, though occasionally imprisoned, never is. But then, director John Milius is telling an origin story: he’s showing us Conan’s struggle to become himself, where Howard simply gives us Conan readymade. The Cimmerian never gets a backstory; he doesn’t need one. His adventures aren’t a roaring rampage of revenge for some deep-seated psychological trauma, or an attempt to prove himself to a distant and disapproving father, but simply a competent, agentic individual determined to “live deep while I live.” When Conan battles evil, it’s typically not because it’s harmed or threatened him personally but because it’s there and he’s the one who can. This isn’t an ethos that one finds in much fiction these days — even our superheroes need origin stories not just of their powers but of their desire to fight crime — but it’s one that Howard, who spent his teenage years in a Central Texas oil boom town, drew from life. In 1935, he wrote to Clark Ashton Smith:

It may sound fantastic to link the term “realism” with Conan, but as a matter of fact — his supernatural adventures aside — he is the most realistic character I ever evolved. He is simply a combination of a number of men I have known, and I think that’s why he seemed to step full-grown into my consciousness when I wrote the first yarn of the series. Some mechanism in my sub-consciousness took the dominant characteristics of various prizefighters, gunmen, bootleggers, oil field bullies, gamblers, and honest workmen I had come in contact with, and combining them all, produced the amalgamation I call Conan the Cimmerian.

But no one writes men like that any more, possibly because no one knows men like that any more, possibly because men like that don’t exist any more. There are vanishingly few places left for them; it’s all “owned space” now. If you see evil, you’re supposed to alert the authorities; if you take matters into your own hands because the authorities can’t show up in time, or they’ve decided that sort of evil is politically undesirable to thwart, you’re liable to be the one punished. We’re no longer supposed to take the initiative — for ourselves, our families, our communities — because we might do it wrong. The process is what matters. We’re supposed to go through channels and leave it to the experts. Can’t you see the viral tweets? “I’m a religious studies professor, here’s why you shouldn’t go toe-to-toe with Thugra Khotan, high priest of Set. 🧵”

Our storytellers’ obsession with revenge dramas and tragic backstory — the recent BBC series even gives one to Sherlock Holmes, who is possibly the least in-need-of-explanation character ever — is a necessity when appealing to an audience unable or unwilling to break out of the suffocating regime of health, safety, and productivity. The protagonist’s very agon, his taking his fate in his own hands, is no threat to you, they say. It’s okay that you, Joseph P. Schmoe, don’t try to chart your own path in the world; you’re not expected to, because you haven’t been forged into a hero in the crucible of suffering. We’re simply no longer willing to admit that sometimes a man is just like that: not because someone has kidnapped his daughter, or killed his dog, or framed him as a spy and imprisoned him in the Chateau d’If for fourteen years, but because that’s who he is.4 Show them a disinterested outsider who steps forward to protect the helpless and they’ll scoff that it’s unrealistic. No one does that! And then someone in real life does it, and they demand he be charged with murder, and they blink.

Whether you read Howard’s stories in the order he wrote them or in the order they were published in Weird Tales (there are slight discrepancies between the two), you’ll meet Conan at various points throughout his life and quite out of any logical order. Here he’s a king, there a young thief, elsewhere a pirate or a mercenary captain or the sole survivor of a slaughtered band of kozaks.5 This was, again, on purpose: “The average adventurer,” Howard wrote, “telling tales of a wild life at random, seldom follows any ordered plan, but narrates episodes widely separated by space and years, as they occur to him.” Sometimes there are connections between the tales — The Scarlet Citadel mentions a piratical past that we see begin in the later Queen of the Black Coast, and Black Colossus first sets Conan’s feet on the path we’ve always known will lead to the throne of Aquilonia — but by and large these are curiosities. The obsessive fan chronologies (there are at least three major ones, plus a 1938 fanzine article that Howard saw in draft form before his suicide) based on maps, the appearance of various articles of clothing, and internal references miss the point: we don’t need to know whether he was a chieftain of the Afghuli tribesmen before or after he led the kozaks. The stories all make perfect sense told in this disjointed order, and that’s because Conan doesn’t really change.

This may seem like an exaggeration — after all, over the course of his career Conan goes from a young thief “too new to civilization to understand its discourtesies” to a middle-aged king behind an ivory writing desk, updating the court’s maps with his own hand and reflecting on poetry, diplomacy, and statecraft — but those are simply shifts of knowledge and scenery, like Sherlock Holmes’s growing fame permitting entrée to cases involving the crowned heads of Europe. Conan remains recognizably the same person, with the same goals and the same reactions, throughout his life, simply working out his fundamental character under different circumstances. This is obvious from his first story, The Phoenix on the Sword, which shows all this is microcosm: our first glimpse of Conan may be as a studious monarch, but the veneer of civilization is torn away almost at once. Howard sums it up in one of the brief epigraphs that allowed him to exercise his (sadly underutilized because sadly unmarketable) talent for poetry:

What do I know of cultured ways, the gilt, the craft and lie?

I, who was born in a naked land and bred in the open sky.

The subtle tongue, the sophist guile, they fail when the broadswords sing;

Rush in and die, dogs—I was a man before I was a king.

But the continuity of Conan’s character is evident across the stories as well as within them. The man who in The Scarlet Citadel refuses to save his own life by abdicating his throne and “sell[ing] his subjects to the butcher” — “thus subtly does the instinct of sovereign responsibility enter even a red-handed plunderer sometimes,” Howard remarks — is recognizably the same as the one who, dying of thirst in the desert at the opening of Xuthal of the Dusk,6 tells his companion to “drink till I tell you to stop” so she’ll finish their canteen. He risks himself repeatedly, in contexts I won’t spoil, to protect the weak — admittedly often attractive women, especially in the era when Howard was hard-up for cash and Weird Tales covers were drawn by Margaret Brundage, who was particularly good at heaving bosoms, but it’s not limited to women. In The People of the Black Circle7 he refuses to desert his followers even if they deserted him first; in Queen of the Black Coast his headlong flight to the sea is driven by loyalty to a friend:

“Well, last night in a tavern, a captain in the king’s guard offered violence to the sweetheart of a young soldier, who naturally ran him through. But it seems there is some cursed law against killing guardsmen, and the boy and his girl fled away. It was bruited about that I was seen with them, and so today I was haled into court, and a judge asked me where the lad had gone. I replied that since he was a friend of mine, I could not betray him. Then the court waxed wroth, and the judge talked a great deal about my duty to the state, and society, and other things I did not understand, and bade me tell where my friend had flown. By this time I was becoming wrathful, for I had explained my position. But I choked my ire and held my peace, and the judge squalled that I had shown contempt for the court, and that I should be hurled into a dungeon to rot until I betrayed my friend. So then, seeing that they were all mad, I drew my sword and cleft the judge’s skull.”

The sort of “skipping about” that works so well for Conan would make no sense for the story of an Ebenezer Scrooge, or a Michael Corleone: those are stories about a person changing, so tracing the character’s arc through time is vital.8 And that’s a fine sort of story to tell — goodness knows we all grow and change throughout our lives — but it’s not the only kind. Writer and game designer Robin Laws draws a dichotomy between these two sorts of stories with their two sorts of heroes: the “dramatic hero” is changed by his experience of the world, while the “iconic hero” changes the worlds by remaining true to himself. It should be clear where Conan, as well as other perennial favorites like Sherlock Holmes, James Bond, or Indiana Jones fall here; the iconic hero is particularly well-suited to serialization because he can be counted on to continue doing the thing the audience loved him for in the first place. He doesn’t have a character arc. He finishes each story much the same person as he began it, aside from perhaps a few new scars or an enhanced reputation. And so network TV is still full of iconic characters, but fiction, film, and “prestige cable” are increasingly hostile to them — in large part, I think, because of the cult of the origin story, which is definitionally a dramatic character arc. (The protagonist goes from, say, dopey farmboy to Jedi Knight.) An iconic hero can be introduced with a dramatic change — Batman, who is obviously an iconic hero, is perhaps the Ur-example of a tragic backstory employed to justify superhuman heroism — but he doesn’t need one, and he especially can’t keep having them after he’s become his iconic self or else he’s no longer iconic. Hollywood, no longer willing to show exceptional individuals without explaining away their superlative qualities, has so imprinted on the dramatic arc as integral to storytelling that they’ve quite forgotten how to tell other sorts of stories: every film either spends half its time showing us how the hero became the guy who does whatever-it-is-we’ve-come-to-see, or pretends to put his continued doing-whatever-it-is-we’ve-come-to-see in jeopardy, rather than simply having him do the thing.9 Conan, as ever, is a refreshing corrective.

The typical Conan story drops the reader into the midst of some complicated (usually magical) problem of wicked old civilization — a sorcerous conspiracy to murder a king, the hideous remnants of a primordial race rising from their moldering ruins, an arcane heist gone awry — and only then introduces the Cimmerian. He’s no dumb brute, smashing where he will, but his approach to these predicaments is generally, uh, direct, in repeated and explicit contrast to the ways of “civilized men.” There’s a nice analogy in an early scene of The Tower of the Elephant; here a young Conan has stripped to loincloth and sandals and is moving “with the supple ease of a great tiger, his steely muscles rippling under his brown skin”:

He had entered the part of the city reserved for the temples. On all sides of him they glittered white in the starlight — snowy marble pillars and gold domes and silver arches, shrines of Zamora’s myriad strange gods. He did not trouble his head about them; he knew that Zamora’s religion, like all things of a civilized, long-settled people, was intricate and complex, and had lost most of the pristine essence in a maze of formulas and rituals. … His gods were simple and understandable; Crom was their chief, and he lived on a great mountain, whence he sent forth dooms and death. It was useless to call on Crom, because he was a gloomy, savage god, and he hated weaklings. But he gave a man courage at birth, and the will and might to kill his enemies, which, in the Cimmerian’s mind, was all any god should be expected to do.

Conan is fundamentally a man of action. Though we usually meet him in circumstances not of his making — even the stories of the form “Conan sets out to do X and accomplishes it” are full of unexpected encounters with the lurking remnants of civilizations unimaginably past — he never seems like an object of forces outside his control. Rather, the more elaborate the set-dressing, the greater the weight of history and mythic resonance, the more satisfying it is when Conan slices through it all like Alexander with the Gordian Knot. He’s simply stronger, faster, and more perceptive than everyone else, possessed of an innate understanding of the world, because he is outside civilization: “He was not merely a wild man; he was part of the wild, one of the untamable elements of life; in his veins ran the blood of the wolf-pack; in his brain lurked the brooding depths of the northern night; his heart throbbed with the fire of the blazing forests.” Or take this passage from early in The Pool of the Black One, where a pirate captain is fighting for his life:

[He] was the veteran of a thousand fights by sea and by land. There was no man in the world more deeply and thoroughly versed than he in the lore of swordcraft. But he had never been pitted against a blade wielded by thews bred in the wild lands beyond the borders of civilization. Against his fighting-craft was matched blinding speed and strength impossible to a civilized man. Conan’s manner of fighting was unorthodox, but instinctive and natural as that of a timber wolf. The intricacies of the sword were as useless against his primitive fury as a human boxer’s skill against the onslaughts of a panther.

Howard was obsessed with the contrast between barbarism and civilization. (So, of course, are we.) He and Lovecraft had a long exchange of letters on the topic (obligingly glossed in two parts here and here, for those of us who aren’t shelling out the $60 for their two-volume collected correspondence), with the Rhode Islander taking the part of civilization and the Texan that of the barbarians. Howard wrote that in his dreams, “Always I am the barbarian, the skin clad, tousle haired, wide-eyed wild man, armed with a rude axe or sword, fighting the elements and wild beasts, or grappling with armored hosts marching with the tread of civilized discipline, from fellow fruitful lands and walled cities. …when I begin a tale of old times, I always find myself instinctively arrayed on the side of the barbarian, against the powers of organized civilization.” His interest in any historical period faded, he added in another letter, as its people began to become civilized: “My study of history has been a continual search for newer barbarians, from age to age.” But he claimed not to idealize barbarism: “I have no idyllic view of barbarism—as near as I can learn it's a grim, bloody, ferocious and loveless condition. I have no patience with the depiction of the barbarian of any race as a stately, god-like child of Nature, endowed with strange wisdom and speaking in measured and sonorous phrases.”

And yet Conan’s barbaric virtue is visible not only in his physical prowess, but in a loyalty, honesty, and fundamental decency that contrasts sharply with the deceit and guile of “civilized” men. In The God in the Bowl, the young Cimmerian thief refuses to betray the man who hired him to the authorities (and is furious and vengeful when the employer betrays him in turn). In Rogues in the House, he promises his services in return for a jailbreak, ends up escaping on his own, and nevertheless decides that he is indebted and must fulfill his end of the bargain anyway. He’s infuriated by the “civilized” practice of human sacrifice (“I’d like to see a priest try to drag a Cimmerian to the altar! There’d be blood spilt, but not as the priest intended”), and in Iron Shadows on the Moon a captive princess shocks him with the depravity of her kind:

“I am a daughter of the king of Ophir,” she said. “My father sold me to a Shemite chief, because I would not marry a prince of Koth.”

The Cimmerian grunted in surprise.

Her lips twisted in a bitter smile. “Aye, civilized men sell their children as slaves to savages, sometimes. They call your race barbaric, Conan of Cimmeria.”

”We do not sell our children,” he growled, his chin jutting truculently.

Later, she reflects that “[s]he had never encountered any civilized man who treated her with kindness unless there were an ulterior motive behind his actions. Conan had shielded her, protected her, and — so far — demanded nothing in return,” and several other princesses (I told you there was a heaving bosoms phase) feel the same way. Likewise, Conan’s kingship is better than those to the manor born: “I found Aquilonia in the grip of a pig like you,” an older Conan tells a would-be usurper, “one who traced his genealogy for a thousand years. The land was torn with wars of the barons, and the people cried out under oppression and taxation. Today no Aquilonian noble dares to maltreat the humblest of my subjects, and the taxes of the people are lighter than anywhere else in the world.”

We never meet another Cimmerian. Conan speaks only once of his homeland: “a gloomier land there never was — all of hills, darkly wooded, under skies nearly always gray, with winds moaning drearily down the valleys.” Aquilonia — and secretive, shadowy Zamora and the jungle-shrouded southern coasts and a dozen other places besides — are far more to his taste. His is a thirst to see the world, to experience all its richness and splendor: “Let me live deep while I live,” he intones in Queen of the Black Coast, “let me know the rich juices of red meat and stinging wine on my palate, the hot embrace of white arms, the mad exultation of battle when the blue blades flame and crimson, and I am content. … I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.” There is a real sense of sorrow to it all, though: to Howard’s portrayals of decaying, self-destructive debauchery and crumbling stone where once there were colossal cities, but also to Conan’s passionate present. We see civilizations that have risen and fallen unfathomable eons into the past, and we know that the glories of this age undreamed of — its gilded mail, its lion banners — will vanish in a cataclysm that brings about our own world.

I joked in my review of Bronze Age Mindset that Robert E. Howard could have written it, and there’s something to that: Conan is a vitalist hero, the reaver and raider and pirate, the truly free man who is not an object of Fate or History or Social Forces but a subject choosing and doing and making history for himself. But look a little closer and the differences are stark, because while we’re always told that Conan is pillaging and burning and looting, what we’re actually shown is Conan shielding the weak and slaying the wicked. Yes, Howard sees civilization as a temporary condition that will inevitably succumb to external enemies or decline under the weight of its own degradation, but it’s still worth fighting to postpone that day. Conan may be stronger and better than civilized men because he comes from outside civilization — he may wear it as only a thin coat (of silk and cloth-of-gold, naturally) that can be laid aside or torn away to reveal the red-handed barbarian beneath — but he loves it, too. His infusion of barbaric virtue refreshes it and gives it a new lease on life; his fate is one with his kingdom. Outlander, yes, but he uses those gifts to be the protector of what civilization can and ought to be. There is a splendid moment towards the end of The Scarlet Citadel that rivals anything in Tolkien for monarchical return, a suddenly appearing “wild barbaric figure, half naked, blood-stained, brandishing a great sword,” and from the multitude of civilized folk rises a great roar of welcome to their deliverer: “The king! It is the king!”

Long may he reign.

This is what they call it when you’re dead and someone else writes a story based on your notes, because they think “raping a corpse” isn’t very catchy.

They make wonderful audiobooks, too, if that’s your jam, but do take a peek at the illustrations if you can.

Actually, Elizabeth II would be even more fun.

There’s a similar phenomenon at work with villains, who are also increasingly given tragic backstories — most dramatically in the case of “villain prequels” like Wicked and the recent Cruella de Vil and Maleficent films, and I’m sure there’s a live-action Ursula movie in development. The underlying message is the same, for both, though: it’s okay that you’re borne along by the current because no one actually makes meaningful choices; you may be a character but you don’t have character; you’re just a product of your environment, man.

From The Devil in Iron:

On the broad steppes between the Sea of Vilayet and the borders of the easternmost Hyborian kingdoms, a new race had sprung up in the past half-century, formed originally of fleeing criminals, broken men, escaped slaves, and deserting soldiers. They were men of many crimes and countries, some born on the steppes, some fleeing from the kingdoms in the west. They were called kozak, which means wastrel.

But you could probably guess most of that from the name, couldn’t you?

There’s not really enough detail to be sure Howard meant it, but the circumstances leading up to this are extremely reminiscent of a less successful version of Ten Thousand.

I’m cheating, this story is in the second volume.

Okay, fine, you could do it out of order, but only in such self-consciously “record scratch, freeze frame” sort of way that the structural conceit becomes the whole point of the story, which is definitely not the case with Conan.

My industry friends blame Save The Cat! and my lit theory friends blame Joseph Campbell; I just know it sucks.

> My industry friends blame Save The Cat! and my lit theory friends blame Joseph Campbell; I just know it sucks.

Thank you for saying this!!

Only thing to add-- even Joseph campbell thing is a Hollywood invention, as it was another book by a hollywood guy that made sure that **every** goddamn story now has to follow the Heros Journey.

And great point about iconic heroes-- another thing I hate about modern stories but Hollywood in particular-- the heroes(heroines?) have no moral or value system. They are all tortured souls punching the bad guys to get cheap psychotherapy.

The old school heroes like Sherlock Holmes, Poirot, even the Bronze Man-- these heroes had a value of justice and truth. They solved crime because it was the right thing to do.

I find these modern "tortured" heroes trying to find "redemption" very whiny, narsicisstic and hypocrite. Since they have no values they can do what they want, which is whatever is needed to move the plot forward.

I hadnt read the Conan stories, but I've added the book to my list now

Thank you for this review! I had forgotten how much I loved reading Conan stories in my teen years. I grew up with the Frank Frazetta illustrations, probably part of the edited versions you discussed. I had no idea such liberties had been taken. And I even saw both Conan movies that Arnold made, although not really that impressed by them. However, one line did stick in my brain, and I repeat it out loud (in character voice) every time I drive past the exit along I-5 in Northern CA: “Zamora”. Yes my family thinks I’m crazy and has no idea what movie I’m referencing! 🤣