REVIEW: The Cruise of the Nona, by Hilaire Belloc

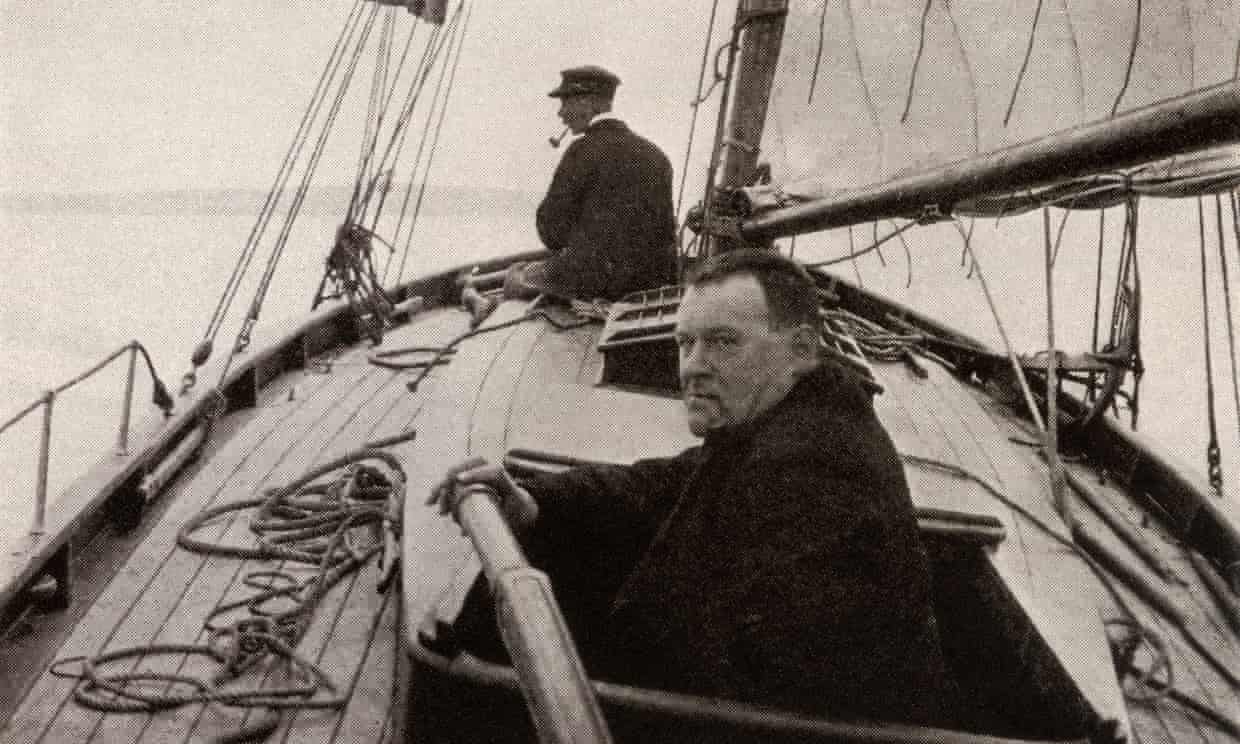

The Cruise of the Nona, Hilaire Belloc (1925; Loreto, 2014).

Late in the May of 1925, around midnight, Hilaire Belloc climbed into a tiny boat and put out to sea so that he would have some time to think. The sea gives ample time to think, especially if like Belloc you disdain the use of a motor. Some wag once jested that sailing is like being at war: long stretches of boredom punctuated by moments of abject terror. I suppose in some sense that’s correct, but give me the boredom of the sailboat any day over the boredom of the trench, the boredom of the cubicle, the boredom of endless doomscrolling.

Sailing is productive boredom, and seems unusually well calibrated for causing the mind to wander in interesting or delightful or just plain ridiculous directions. Maybe it’s the stimulating effects of the wind in your face and the smell of salt in the air, or maybe it’s the weird altered state of consciousness that comes from staring at the ocean. I think it’s because sailing is the human condition in miniature. It places you perfectly-balanced on a knife’s edge between agency and helplessness, and in so doing it both spurs the mind to activity and gives it space to relax and reflect.1

Consider some artificial environments: on the one hand you have the computer role-playing game, a dopaminergic super-stimulus where you are the absolute master of your fate, a Skinner-box so perfect that many never wish to escape. On the other hand, you have a soldier cowering in a foxhole that might or might not be erased by artillery in the next moment. Both hide the true nature of the everyday world, where we are buffeted by luck and knocked around by randomness but where it’s still up to us whether the good luck is exploited, whether the bad luck is managed, and whether we decide to make our own luck.

Unfortunately, the truth that we are simultaneously agentic and helpless is often hidden from us. Our society is woven through with artificial environments, perhaps less extreme than the RPG or the foxhole, but artificial nonetheless. What is the educational system but a Skinner box? What is your dysfunctional corporate job but a learned helplessness simulator? The more time you spend in these contexts, the easier it is to miss the true nature of reality.

On a sailboat, there is no way to hide from reality. When the wind is blowing, you can seize this immortal elemental force with your own strength, skill, and cunning. You can bend it to your desires, compel it to serve you, make it your plaything. And when the wind is not blowing, it doesn’t matter how determined you are, you’re just going to sit there and drift, and the best you can do is laugh like an old Stoic and reflect on the vanity of the world.

Better yet, these abstract truths are communicated with overwhelming epistemic immediacy.2 You trim the sails, the lines creak, the little boat lurches and skips across the waves. Conversely, to be on the water when a storm rolls in is the quickest way in the world to learn that you are nothing, that your life is a puff of air that disturbs some blades of grass for a moment and then is gone. But on a less mystical plane, you also realize in an intensely physical way that how long you have until you return to the dust could depend a great deal on the next few actions you take.

All of this primes you for mental activity, but then most of it actually is quite boring, and so you have a lot of time for the gears to turn. Belloc’s mind is more active than most, so he sits in his boat and thinks. He thinks while he’s becalmed, and he thinks while he’s huddled belowdecks getting battered by a storm, and he thinks while at anchor in little coves, lying on the deck, failing to sleep, getting lost in the ocean of stars above.

What does he think about? Well, all kinds of stuff: the lack of natural ports in North Africa,3 the irreducibly doctrinal nature of conflicts between rival civilizations,4 the greatness of Mussolini,5 how much fun it would be to own an island.6 He muses on the life he wasted trying to have a career in writing, for “a man is no more meant to live by writing than he is meant to live by conversation, or by dressing, or by walking about and seeing the world.” And he fantasizes about seeing his literary rivals “all driven aboard an immense barge, and the same towed out to sea and there scuttled.”

But mostly he thinks about England. England in the grip of “the catastrophic change, the cataract of change… the revolution which has transformed modern England; so that, of all the states I know, none has become so intimately different from its own immediate past.” Englishness is vanishing, but it’s also shedding its skin, desquamating, morphing into something powerful and transnational and surly. The English are vanishing from England, but simultaneously the entire international progressive movement is becoming Anglo-Puritan, WEIRD, spiritually English even when they aren’t aware of it.

There is a delightful irony in observing how intensely national these anti-nationalists are! […] If you wanted to get a specimen — I do not say of the average Englishman, for he is certainly not that — but of a being in whom the English characteristics are to be found most deeply marked, this pacifist is the very man whom you should choose. All the English conceptions of right and wrong, all the English habits of thought, all the sheltered English attitude towards the great outer world, all the local errors, and much of the local generosity are there present to the full.

I cannot help thinking it a strength to England that the pacifist or internationalist in England should be so intensely English. It prevents any disruptive effect, and it, therefore, prevents the rivals of this country from taking such folk seriously.

The French and Italians are far less happily circumstanced in this regard. In those two countries… the internationalist is an internationalist, bearing but weakly the common marks of his own people, and willing to act not only against his country politically, but also in all his being, morally and spiritually. A French or Italian internationalist and pacifist will not only sympathise with the enemies of his country, nor only give them actively all the help he can, but he will particularly attack the soul whereby his country lives, its traditions and character… The unrooted man is a very dangerous type, and in England happily unknown.

Anybody who’s travelled extensively in the third world has seen the modern version of this. There’s nothing intrinsic to being a reformer or a liberalizer that makes you an agent of American power, and yet…there’s a better than even chance that you are. After a while these people all blend together — the idealistic students, the LGBT activists, the NGO staffers, the embassy employees recruited from amongst the locals. They come from a hundred nations, from every conceivable race and religion, and yet something invisibly and inexorably molds them all into the same shape, like iron filings lining themselves up in the presence of a powerful magnet.

Soon they have American souls, and divided loyalties to match. The local regime panics and views them as an internal enemy, which only furthers their alienation from their motherland and their flight into the bosom of Global America. Most empires rule primarily though influence, not coercion, and this class of people is one of America’s most powerful weapons for maintaining and extending its hegemony.

A related phenomenon is the awful sameness that is slowly taking over the whole world. Perhaps your cruise ship docks at a dozen ports over the course of its journey, and every one of them looks exactly the same — the same tiki bar with the same sign, the same shops selling the same ornamental kitsch probably all made in the same factory. You aren’t visiting a place, you’re visiting a psychic manifestation of the Buffetverse, another outpost of Margaritaville, a Potemkin seaport with frozen daiquiris. You all know what I’m talking about. We make fun of it all the time, because cruise ships are for chuds. But it doesn’t just happen with cruise ships.

The cancer usually starts in an international airport. Form follows function, so it’s superficially reasonable that every airport on earth should look and feel exactly the same. But the real reason is that it follows in the wake of the kinds of people who fly into those airports, praising the broadening effects of foreign travel whilst terraforming everything they touch until it resembles the “arts district” of a midsize American city, replete with distressed wood finishes, gravid with craft beers. Real foreignness would cause these people to recoil in shock, or to demand a peacekeeping intervention. It’s not unusual for the imperial functionary class to be parochial, but what’s surreal about ours is how they combine the blinkered innocence of a farm boy with an ideology of weary cosmopolitanism.

None of this was as far along when Belloc took his little cruise, but the seeds had been planted, and he could feel in his bones that something horrible lay across the horizon. So he fights it the only way he knows how — by noticing and celebrating everything distinctive and local and weird about every place he visits. No island is too small for him to mention by name and recall a ghost story or two associated with it. No village is too commonplace for him to remark on the habits, physiognomy, and vices of the people who live in it. It’s the same spirit as that which animates Chesterton’s essay on cheese, but applied to a hundred hamlets and fishing ports, a paean to the regional diversity and distinctiveness that was already slipping away.

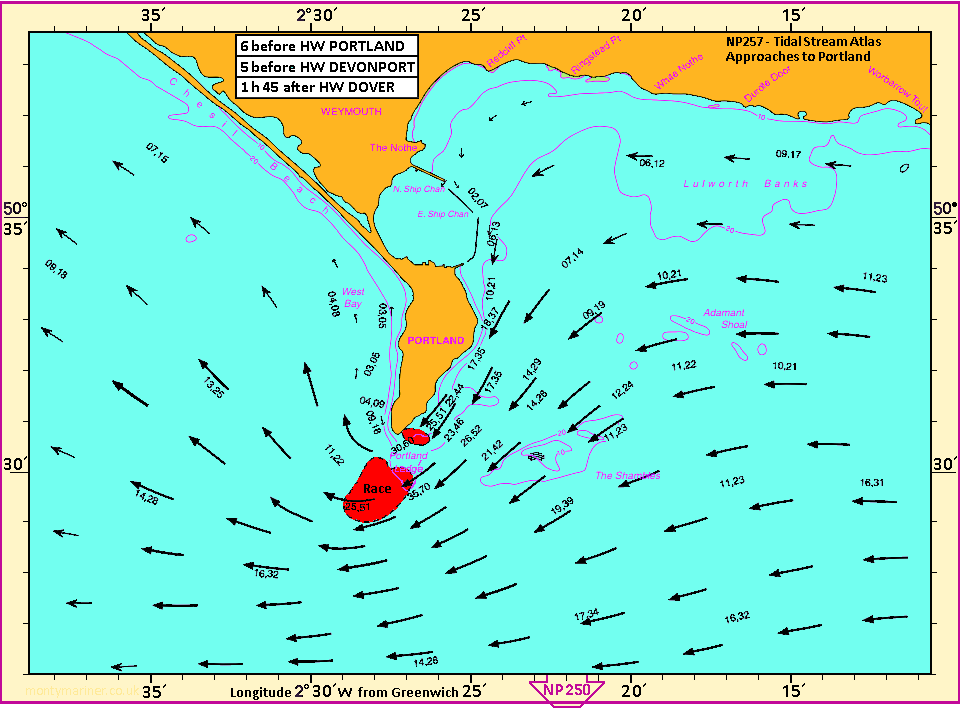

But the best is when Belloc takes this attention to detail and this celebration of particular places, and applies it with redoubled intensity to oceanographic features. Like any real sailor, he views most of them with an attitude ranging from suspicion to outright hostility.7 The nastiest bit of water he encounters is probably the tidal race off Portland Bill.

It’s no Saltstraumen or Corryvreckan, but it’s enough to inspire thoughts like this:

I will maintain with the Ancients that there are some parts of the sea upon which a God has determined that there shall be peril: that these parts are of their inward nature perilous and that their various particular perils are but portions of one general evil character imposed by The Powers. For you will notice that wherever there is one danger of the seas there are many. If it is an overfall or a race then in that neighborhood you will also have reefs, unaccountable thick weather, shifting soundings, bad holding and all the rest of it. Witness the Western approach to the Isle of Portland, or the Bight of St. Malo, with the Channel Islands and their innumerable teeth; the entry to the Straits of Messina and other places recorded in histories and in pilot books. Our moderns will have it that such things are chance and an accumulation of them a blind accident, but I hold with those greater men, our Fathers. Some one here in these places, some early captain, first sailing offended the Gods of the Sea.

This piling up of examples and detailed description of particular places serves a dual purpose. Part of it is a rebellion against the forces of homogenization, but Belloc is also attempting to live up to a theory of knowledge that he only makes explicit towards the end of his voyage. Why do people believe things? Generally because they think something else implies that belief. That “something else” can be raw sensory data, or it can be another belief. But even in the case where our belief is primarily motivated by something we see or feel directly, that connection is mediated by an interpretation of the sensory experience, and that interpretation is another belief.

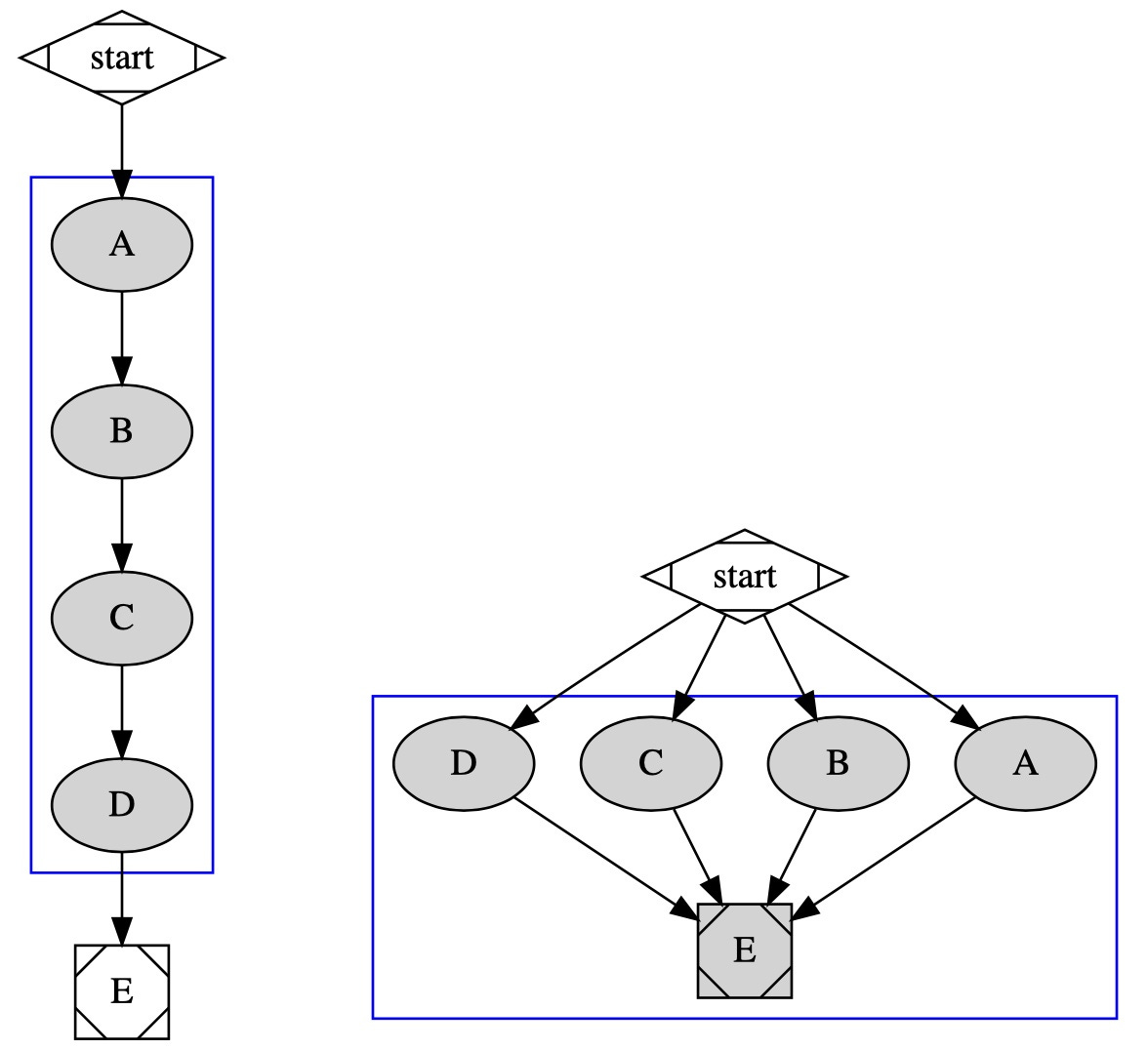

So we believe because we believe, so far so Bayesian. What’s new about this? But Belloc now makes an argument that the large-scale graph structure of our beliefs is in some cases more important than the mere conditional probabilities we assign to the edges. Consider two situations: in the first, A implies B, which in turn implies C, which then implies D, which finally implies E. Moreover, we are quite certain about each of these implications. In the second situation, A, B, C, and D are all pieces of evidence pointing towards E, but our confidence in each of them is much lower.

You can assign numbers to all the edge weights in these belief networks such that a naive Bayesian will go off and do his calculations and tell you that the confidence with which you should hold belief E is the same in both cases. But does this make any sense at all? No matter what the probabilities are, these two graphs have a fundamental, qualitative difference: the one that looks like a chain is fragile in the sense that revisiting any one of the implications has a huge effect on our confidence in the ultimate conclusion: E. The one that looks like a diamond can easily shrug off the loss of one or two of those implications.

It gets worse — in real life, we don’t actually know what the conditional probabilities in our Bayesian belief network are! Maybe we have a confidence interval for each one, but in the case of the chain, the final confidence that we assign to E is much more sensitive to variation in the probabilities of all the preceding implications. And then there’s Knightian uncertainty: we could also just be wrong about something, and again that matters a lot more in the case of the chain. Outside the world of Bayes cultists, actual working scientists have long known that the shape of the graph matters as much as the edge probabilities. For instance, the jargon for this in theoretical physics and cosmology is “tweak theories are weak theories.”

Belloc’s critique of modernity is founded on the view that most modern beliefs are “tweak theories,” that they have an epistemic structure that looks a lot like the diagram on the left. This is especially true of some of the “luxury beliefs” that everybody pretends to hold, or at best half-believes, for reasons of social convention. But he also thinks it’s true of a vast amount of academic output, because academics are addicted to “overturning” received and conventional wisdom but get little in the way of negative feedback since “the power to affirm anything at will to an audience of young and quite unread undergraduates, without fear of contradiction or examination, produces an impotent sort of pride.”

There are a lot of examples of academic fields attempting to overturn “traditional knowledge” and huffing their own exhaust to the point that they’ve utterly convinced themselves, before having it all collapse again. We’ve previously talked about the debacle that was 20th century archaeology. Biblical source criticism is another good example — modern academics got so giddy at the prospect of disproving traditional beliefs about which gospels were written when and by whom that they produced a totally self-referential mountain of circular reasoning that hung in the air for a beautiful moment before collapsing entirely (an obscure German theologian once wrote a pretty good series of books about this). Belloc’s prescription for those in the grip of this sort of delusion is to go outside and touch waves, for:

The sea teaches one the vastness and the number of things, and, therefore, the necessary presence of incalculable elements, perpetually defeating all our calculations. The sea, which teaches all wisdom, certainly does not teach any man to despise human reason… No one can at sea forego the human reason or doubt that things are things, or that true ideas are true. But the sea does teach one that the human reason, working from a number of known premises, must always be on its guard, lest the conclusion be upset in practice by the irruption of other premises, unknown or not considered.

Highfalutin’ epistemology aside, this is a book about sailing,8 about the pleasures and the perils of taking tiny craft onto the wild, elemental world-ocean. Belloc sticks to an incredibly tame corner of it: he’s messing about in the home waters of Great Britain, not battling 80-foot swells while attempting to round Cape Horn. Nevertheless he experiences everything from the sublime communion with your ancestors that comes from knowing you’re doing the same thing they once did, to the absolute depths of ennui and despair, to a joy and serenity so profound he has no way of interpreting it save as a preview of the life to come. It’s an invitation to sail, and so uncharacteristically for these reviews, I’ll let him have the last word, because I want you, dear reader, to receive that invitation too.

The sea is the consolation of this our day, as it has been the consolation of the centuries. It is the companion and the receiver of men. It has moods for them to fill the storehouse of the mind, perils for trial, or even for an ending, and calms for the good emblem of death. There, on the sea, is a man nearest to his own making, and in communion with that from which he came, and to which he shall return. For the wise men of very long ago have said, and it is true, that out of the salt water all things came. The sea is the matrix of creation, and we have the memory of it in our blood.

But far more than this is there in the sea. It presents, upon the greatest scale we mortals can bear, those not mortal powers which brought us into being. It is not only the symbol or the mirror, but especially it is the messenger of the Divine.

There, sailing the sea, we play every part of life: control, direction, effort, fate; and there can we test ourselves and know our state. All that which concerns the sea is profound and final. The sea provides visions, darknesses, revelations. The sea puts ever before us those twin faces of reality: greatness and certitude; greatness stretched almost to the edge of infinity (greatness in extent, greatness in changes not to be numbered), and the certitude of a level remaining for ever and standing upon the deeps. The sea has taken me to itself whenever I sought it and has given me relief from men. It has rendered remote the cares and the wastes of the land; for of all creatures that move and breathe upon the earth we of mankind are the fullest of sorrow. But the sea shall comfort us, and perpetually show us new things and assure us. It is the common sacrament of this world. May it be to others what it has been to me.

Oh hey, it’s the focused-mode and diffuse-mode of cognition! The best way to think deeply about anything is to toggle between them.

And as Belloc notes, the physical confirmation of a truth abstractly known creates a doubly-powerful effect:

“Corroboration by experience of a truth emphatically told, but at first not believed, has a powerful effect upon the mind. I suppose that of all the instruments of conviction it is the most powerful. It is an example of the fundamental doctrine that truth confirms truth. If you say to a man a thing which he thinks nonsensical, impossible, a mere jingle of words, although you yourself know it very well by experience to be true; when later he finds this thing by his own experience to be actual and living, then is truth confirmed in his mind: its stands out much more strongly than it would had he never doubted.”

Sailing is nothing but lessons like that, from the first moment you stand atop a boat that’s making progress into the wind.

“There are not four natural land-locked harbours, I believe, in the whole line of coast from Alexandria round by Barbary and the West, up from the Cape to the head of the Red Sea. The most that man can do is to use the shelter of islands, or the curl of a headland, or here and there a small and insufficient recess, or the mouth of a river. The French have made their small harbours in North Africa artificially, and Alexandria is artificial.”

Belloc is correct about this, and there are some very interesting geological reasons why. Origins by Lewis Dartnell has a whole chapter on this. If you recognize that name, it may be because you read Jane’s review of his other book.

“It is, indeed, a truth which explains and co-ordinates all one reads of human action in the past, and all one sees of it in the present. Men talk of universal peace: it is only obtainable by one common religion. Men say that all tragedy is the conflict of equal rights. They lie. All tragedy is the conflict of a true right and a false right, or of a greater right and a lesser right, or, at the worst, of two false rights. Still more do men pretend in this time of ours, wherein the habitual use of the human intelligence has sunk to its lowest, that doctrine is but a private, individual affair, creating a mere opinion. Upon the contrary, it is doctrine that drives the State; and every State is stronger in the degree in which the doctrine of its citizens is united. Nor have I met any man in my life, arguing for what should be among men, but took for granted as he argued that the doctrine he consciously or unconsciously accepted was or should be a similar foundation for all mankind. Hence battle.”

“I made a sort of pilgrimage to see Mussolini, the head of the movement, and I wrote about him for the Americans. I had the honour of a long conversation with him alone, discovering and receiving his judgements. What a contrast with the sly and shifty talk of your parliamentarian! What a sense of decision, of sincerity, of serving the nation, and of serving it towards a known end with a definite will! Meeting this man after talking to the parliamentarians in other countries was like meeting with some athletic friend of one’s boyhood after an afternoon with racing touts; or it was like coming upon good wine in a Pyrenean village after compulsory draughts of marsh water in the mosses of the moors above, during some long day’s travel over the range.”

For some inexplicable reason, Belloc’s modern fans tend not to talk about his infatuation with Mussolini (there are pages of stuff like the quoted passage above). But I’m inclined to give them a break, since a lot of other Mussolini fandoms have been airbrushed from history (including the entire American progressive movement of the 1920s and 1930s, together with everybody in charge of the New Deal).

“But what I should most like to know (only I have never met any one who could tell me) is whether the pleasure of isolation which these places afford increases with the years, or at last becomes intolerable? I knew a man once who, during all the latter part of his life, was torn between the desire of possessing an island, and his fear lest ,once had bought it, he should find that he had purchased misfortune. All his friends told him that islands were like those legendary objects of bad luck which one man has to pass on to another and which each new holder soon finds unendurable. To be king of one’s own land, to be quite cut off from the complexity and futilities of the world, to have a little country all of one’s own, neatly bounded, inaccessible if one chooses to make it so — that is enough to tempt any one who has lived among men. But I am assured by many who have not themselves tried it, that after a very short experience in such things one has no desire but to be rid of them.”

“Lord, what a tangle of dangers are here for the wretched mariner! Rocks and eddies and overfalls and shooting tides; currents and… horrible great mists, fogs, vapors, malignant humours of the deep, mirages, false ground, where the anchor will not hold, and foul ground, where the anchor holds for ever, spills of wind off the irregular coast and monstrous gales coming out of the main west sea…”

This is NOT a book about racing, mind you. Belloc rightly considers boat races to be an abomination that lead to evils such as materialism, technology, and auxiliary motors.

An absolute delight from beginning to end.

On the particular point regarding the pleasure of doing as generations prior have, I've been mulling over this for some time, with still half formed thoughts.

I work near a street market in the City of London that's been going on since the seventeenth century or so, and I do take satisfaction being simply yet another financier grabbing a quick lunch in this same spot. Hardly an ancient communion with wrathful nature, but a kind of communion nonetheless.

And yet, what about this in particular gives pleasure? Getting stuck in traffic is also an age old London tradition, but hardly ancestrally evocative.

I've almost come to think that the meaningfulness of these actions has less to do with any actual history in them per se, but rather an anti-ephemerality, a sense that these are actions we could hope and imagine our own descendants (whether physical or spiritual) doing; the kind of thing for which we could *be* the ancestors.