REVIEW: The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, by Edward Luttwak

The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire: From the First Century CE to the Third, Edward N. Luttwak (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976).

In one of the dozens of notorious interviews of Edward Luttwak that float around the internet, he’s asked how he chose the topic for his PhD dissertation. His answer is that one day at university he had a humiliating social encounter. Immediately afterwards, somebody pounced on him and asked what his dissertation was about anyway. He hadn’t even started thinking about what his topic would be, but he obviously couldn’t say that, and so instead he puffed himself up and made something up on the spot, and he did so by saying the most grandiloquent series of words one at a time like a large language model feverishly choosing the next token to maximize self importance: “The… GRAND…. Strategy… … OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE!!” His interlocutor was sufficiently awed and impressed, but then he had to write the damn thing. Like all Luttwak stories, this is probably false but totally believable.1

But I’m very glad he wrote that thesis, because it was later turned into the wonderful book I’m reviewing. Now, one of the ways that the Psmiths subvert traditional gender roles is that it’s Jane, not I, who thinks about the Roman Empire every day. But this is only pretending to be a book about the Roman Empire. It’s really a book about “grand strategy” — how states can efficiently allocate scarce military, diplomatic, and financial resources to counter a variety of internal and external threats. It’s true that the examples are mainly drawn from four centuries of Roman history — starting with the Julio-Claudian dynasty and ending with the Empire losing control of Italy and Western Europe — but the analysis, and the lessons, are abstract enough that they transcend that particular context.

Luttwak believes that the state is a kind of machine for turning arable land into military power via taxation and conscription. A state that wants to maximize its survival odds can do so in three ways: (1) it can increase its “inputs”, by bringing a larger quantity of arable land under its control (so long as it avoids a commensurate increase in the threats it faces); (2) It can increase the efficiency of the machine, by extracting more grain and more labor from the people it rules, or by undertaking internal reforms to reduce the amount of potential that’s bled away by corruption and decadence; or (3) It can use its military as effectively as possible, doing more with less, killing many birds with one stone or setting up situations where a small allocation of force can tie down much larger opponents.

This third option is more or less what Luttwak means by “grand strategy,” and I think it may be the key that ties together all of Luttwak’s writing and thought. What do a book about the ancient world and a book about Cold War era coups have in common? They’re both about doing more with less, economizing force by wielding it with overwhelming brutality and efficiency. Luttwak’s coldly arithmetic view of the state is reminiscent of nothing so much as James C. Scott’s view of the world,2 but Luttwak is on the opposite team. Scott is an anarchist, Luttwak is a hard-boiled realist, and moreover he’s one with a deep aesthetic appreciation for power and violence, especially when used elegantly, like a scalpel, such that they have effects far out of proportion with their quantity.3

The history of Rome that Luttwak wants to tell is not the history of its cultural or civilizational achievements, but rather the history of how these people were so incredibly good at economizing on violence that they were able to waste a huge portion of their military and economic potential on civil wars, but still keep the lights on and the barbarians at bay. “Grand strategy” is how they accomplished that, but the strategy changed as the threats evolved and as the internal condition of the empire deteriorated. Luttwak delineates three distinct epochs — the founding of the empire under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the rationalization of frontiers under the Antonine emperors, and the Crisis of the Third Century — and argues that each of the three featured a fundamentally different overall strategic posture on the part of Rome.

But before we get into all of that, I suppose we ought to talk about the legions. When people think of Roman military power, they usually think of the heavily-armed guys with red cloaks and horsehair plumes on their helmets. But of course they only made up a small fraction of the Roman military. We know that this has to be true because ancient armies, as much as modern armies, relied on combined-arms for their success. A legionary was a very scary kind of soldier, combining the roles of heavy infantry and combat engineer, but an army made up entirely of heavy infantry would be shredded by an opposing force of horse archers, for instance. So the Romans brought many other kinds of troops to bear: skirmishers, slingers, archers, light infantry, cavalry of their own (including mounted archers, light cavalry, and lancers with primitive barding that are a clear precursor of Medieval knights). And…almost to a man, all of these other forces were non-Roman.4 They were either mercenaries, or allied barbarians, or auxiliaries. As a kid in ancient history class I just accepted this as a fact, but reflect on it for a second and it seems very weird. This whole arrangement caused the Romans no end of trouble, so why did they do it that way?

Take the Luttwak pill and it all becomes clear: the Romans went all-in on legionaries as a way of economizing on force. The only people Rome could absolutely rely on were her citizens. The definition of a “real” Roman changed over time — at first it was only inhabitants of the city of Rome itself, later it was expanded to the surrounding countryside, and finally to all of Italy. But at every point it was a tiny fraction of the total population of the empire. Of that tiny fraction, some even smaller fraction are available to be trained as soldiers and to bear arms. What do you want those guys to be doing? The Roman answer is that you want them to be legionaries, because legionaries are not general-purpose soldiers, they’re specialists, and their specialties are: (1) besieging enemy cities, and (2) battles of attrition and annihilation.

There’s a useful term in the modern study of international relations, called “escalation dominance.” What escalation dominance means is that in any sort of conflict, there’s a big game theoretic advantage to being the one who decides how nasty it’s going to be. Ancient wars usually moved slowly up a ladder of escalation, from dudes yelling insults at each other across the border, to some light raiding and looting, to serious affairs where armies made an actual effort to kill and subjugate each other or conquer land.5 Highly mobile forces tended to work best at the lower rungs of the escalation ladder, and Rome frequently allowed conflicts to stay simmering at this level. But the existence and loyalty of the legions meant that it was their choice to do so, because they could also choose to slowly and inexorably march towards your capital city killing everything in their path and doing something truly unhinged when they got there, like building multiple rings of fortifications or a giant crazy siege ramp in the desert. And, paradoxically, the fact that they could do this meant that they didn’t have to as often. Thus the threat of disproportionate escalation became the ultimate economizing measure, by preventing wars from breaking out in the first place.

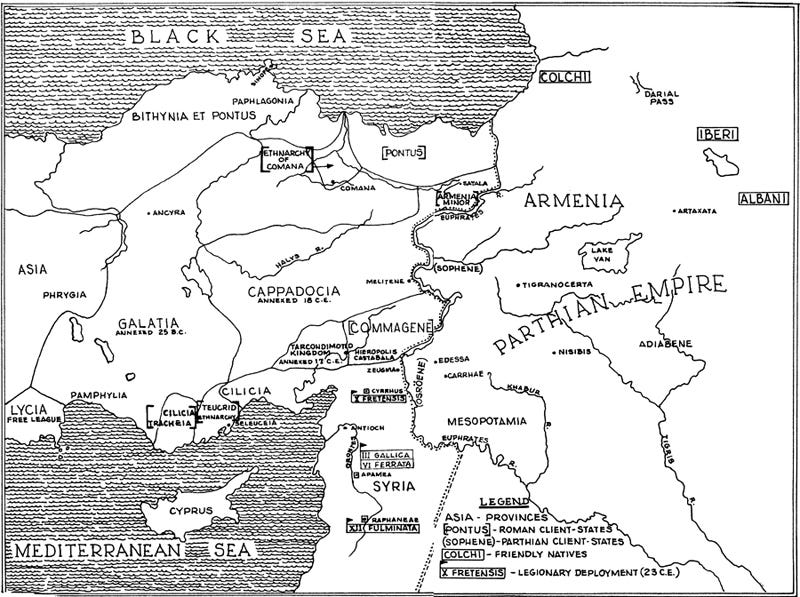

If deterrence fails and you have to fight, then the next best way to economize on force is by making somebody else do the fighting for you. In the late Republic and early Empire, much of Roman territory wasn’t “officially” under Roman rule. Instead, it was the preserve of dozens of petty and not-so-petty kingdoms that, on paper at least, were fully independent and co-equal sovereign entities.6 Rome actually went to some effort to keep up the charade: the client rulers were commonly referred to as “allies,” and Rome took care never to directly tax or conscript their citizens. But, to be clear, it was a charade. If any of these “allies” ever wanted to leave the alliance or conduct any sort of independent foreign policy, he would not continue to be a king for long. Oftentimes the legions wouldn’t even have to show up — the terrified citizens of the client kingdom would overthrow and execute their wayward ruler themselves, in the hopes that Rome might thereby be induced not to make an example of the citizenry.

What was the point of all of this complicated kabuki theater? Once again, it’s about economy of force, this time on both the “input” and the “output” sides of the great machine of the state. On the input side: efficient government is hard to scale. Roman provincial governors were legendarily corrupt, and could get up to all kinds of mischief out there without supervision. Having a Roman ruling a whole bunch of non-Romans was also bound to cause resentment: it could lead to rebellions, or worse, tax-evasion. All of these problems were solved by pretending to have the barbarians be ruled by one of their own, a barbarian king. He could collect the taxes, and suppress revolts, and generally keep an eye on things. Moreover, as a fellow barbarian, he would know better how to keep his subjects in line, and would be less likely to commit an awkward cultural blunder. On the output side, he could also deal with border raids and other low-intensity threats. This exponentially magnified Roman military power, because it meant that instead of being stuck on garrison duty, spread out along the frontiers, the legions could be concentrated in a strategic reserve. They could then be deployed for “high intensity” operations in some remote part of the empire without worrying that they were thereby leaving the borders unguarded: operations like conquering new lands, or persuading a rebellious client kingdom that their interests lay with Rome.

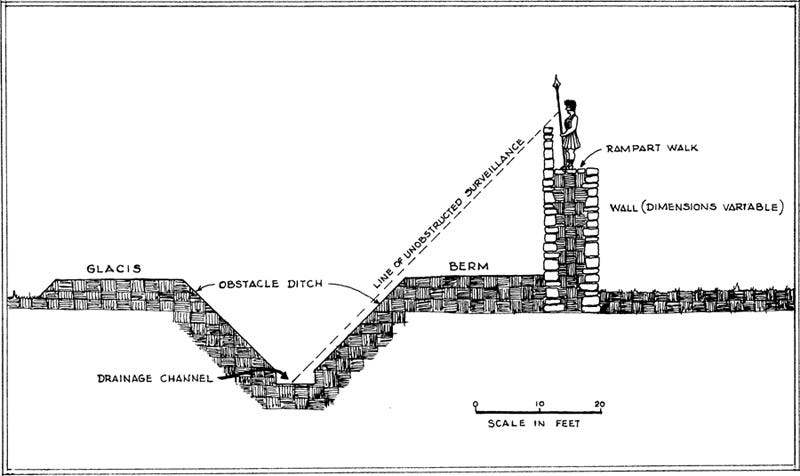

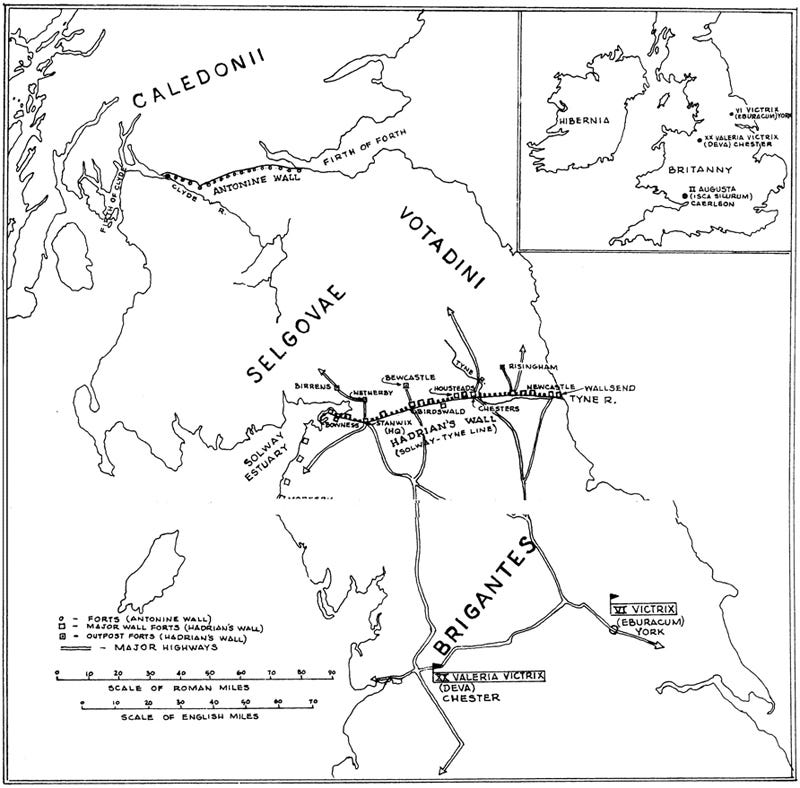

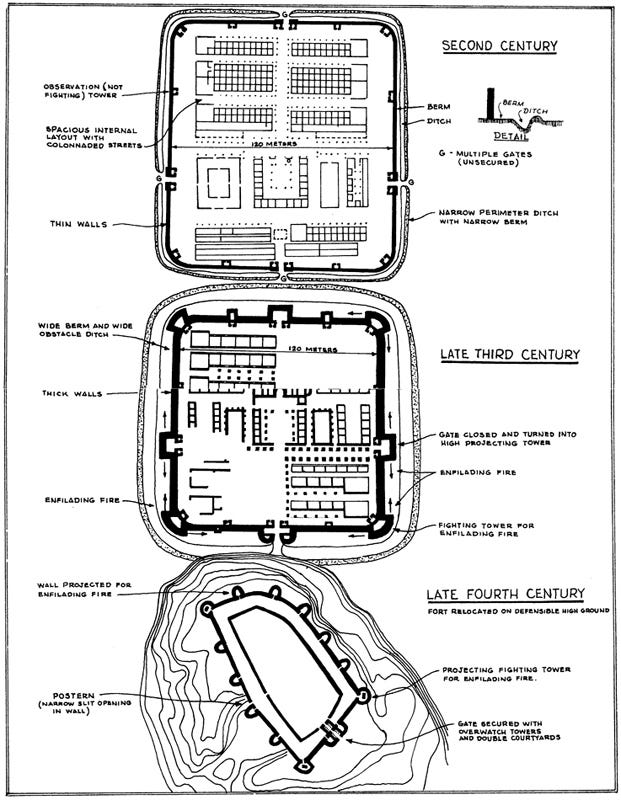

If you can’t make somebody else do the fighting, then the next, next best thing is to carefully choose the time, circumstances, and location of the fight. Ideally you would muster a heavy concentration of your own forces and confront the enemy while they’re still dispersed. Ideally the ground would be thoroughly surveyed, well understood, and perhaps even prepared with static defenses. Ideally your own forces would have ample supply and good lines of communication, and your opponent would have neither of these things. It was to all these ends that in the second of the periods Luttwak surveys, the Romans built the limes7 — a massive system of defensive emplacements. These extended for thousands of miles around almost the entire frontier of the empire, but the most famous portion was Hadrian’s Wall.

As Luttwak notes, modern historians and military theorists have a tendency to sneer at linear defense lines.8 In fact, some historians of ancient Rome actually blame the decline and eventual collapse of the empire on all the “wasted” energy spent building frontier fortifications. The argument against such “cordon” defenses is that for a given quantity of military potential, spreading it out equally along a perimeter and trying to guard every spot equally dilutes your strength. This makes it easy for an attacker (who picks the time and location of the battle) to concentrate his forces, create a local advantage, and break through.

The thing is, approximately none of this logic applied in the Roman situation. First of all, as we’ve already noted, a huge fraction of the threats the Romans faced were “low-intensity”: border skirmishes, slave raids, pirates and brigands, that sort of thing. Static fortifications, walls and towers, are often more than sufficient for dealing with these problems. Paradoxically, that actually increases the mobility and responsiveness of the main forces. If they aren’t constantly running back and forth along the border dealing with bandits, that means they can respond with short notice to “high-intensity” threats (like major invasions and rebellions) that pop up, and are probably better rested and better provisioned when the emergency arrives. So, far from diluting their strength, a lightly-manned series of linear fortifications actually enabled the Romans to concentrate it.

Secondly, those linear fortifications can also be very useful when that major invasion shows up, even if they are overrun. A defense system doesn’t have to be impenetrable in order to still be very, very useful. One thing it can do is buy time, either for the main army to arrive or for some other strategic purpose. The defenses can also act to channel opposing forces into particular well-scouted avenues of attack, or change the calculus of which invasion routes are more and less appealing. Finally, in the process of setting up those defenses, you probably got to know the terrain extremely well, such that when the battle comes you have a tactical advantage.

All of these lessons have recently been learned the hard way by the Russians, the Ukrainians, and the Americans in the current war in the Donbass. It turns out that with 2023-level technology, linear defenses are very powerful indeed, even when it’s possible to breach them. Defenses that “merely” slow down the enemy are actually exceedingly deadly when drone-corrected artillery is in play. And a defensive emplacement that “merely” allows you to predict where a battle will be is a fearsome thing if it means you can saturate the battlefield with ISR assets in advance, map out sight lines, dial in your indirect fires, and so on. The relative advantages of offense vs. defense wax and wane throughout history, and the meta wasn’t quite as strongly in favor of the defender in the ancient world, but the Romans still enjoyed versions of all these advantages.

The third, and perhaps most important, reason why the Roman frontier fortifications were actually very smart is that they were carefully designed to double as a springboard for invasions into enemy territory. Luttwak coins the term “preclusive defense” to describe this approach. The basic idea is that an army can take bigger risks — pursue a retreating foe, seize a strategic opportunity that might be an ambush, etc. — if it knows that there are strong, prepared defensive lines that it can retreat to nearby. Roman armies were constantly taking advantage of this, and moreover taking advantage of the fact that the system of border fortifications was also a system of roads, supply lines, food and equipment storage depots, and so on. The limes were not a wall that the Romans huddled behind, they were a weapon pointed outwards, magnifying the power that the legions could project, helping them to do more with less.

Here I can’t resist a digression that touches on several of my favorite topics: where do you put your defensive lines? One obvious guess is what Luttwak calls “scientific frontiers,” geographic or other natural features such as rivers, mountains, the edges of deserts, places where the land is already bottlenecked. And that’s not bad as a first order approximation, but there are times that other considerations dominate. For example, placing your borders right along the banks of the Rhine and the Danube is actually quite awkward, because the headwaters of those two rivers come together in a sharp “elbow.” This results in a kind of reverse-salient poking into your territory, and making it a much longer journey from one side of the intrusion to the other. Much better to conquer that wedge and push the border out a bit. Yes, the frontier is now marginally harder to defend, but it’s more than made up for by the reduced travel time for the army to get anywhere.

Here’s another one — why is Hadrian’s Wall where it is? There’s a much shorter and more defensible alternate location to the north, where the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde create a natural bottleneck. In fact at one point the Romans did build a wall there and claimed all the intervening territory. On paper, the Antonine Wall looks better in every way than Hadrian’s Wall. It’s shorter, so requires less military “output” to defend. And it encloses more area, so brings to the “inputs” of the machine of state both additional arable land and additional people who can be taxed and conscripted. But as it happened, the Antonine Wall was quickly abandoned, and the empire retreated to Hadrian’s Wall. Why?

It all had to do with the people living between the two walls. They were… hill people who had perfected the art of not being governed. They managed to be so thoroughly intractable, so impossible to control or corral, so very unpleasant to be around, that the Romans eventually threw up their hands in disgust and left them alone. It’s important to understand that this means they must have been true outliers, because the Roman Empire had “unit economics” like an enterprise SaaS business, where “customer acquisition costs” are financed on the assumption that they’ll be paid back in the distant future. Every Roman bureaucrat understood that newly conquered territories would be a drain on fiscal and military resources for a while, until a generations-long process of pacification and Romanization slowly made them net contributors in both departments. But in the case of the lands between the two walls, the payback timeline was so long, and the implied interest rates so high, that even a people as meticulous and relentless as the Romans decided there were better opportunities elsewhere. I count this as a serious victory for the theory of defensive barbarism.

The transition to the third and last of Luttwak’s periods is triggered by an increase in the dangers that the empire faced and a simultaneous decrease in the resources available to counter them, as men and materiel were frittered away in pointless civil wars. Before getting to the resulting shift in strategy, though, I want to mention Luttwak’s fascinating theory of why the barbarian threat got so much worse. He basically posits that that same process of pacification and Romanization was also happening across the frontier, in non-Roman lands, as a sort of Girardian mimesis. A hundred fiercely independent barbarian tribes spent years battling and bumping up against the Roman Empire, and for some of them it unlocked conceptual technologies — nationhood, record-keeping, large-scale organization — that made them much more dangerous opponents. They stared across the frontiers, and they saw the Romans, and they hated them, but they also wanted to be like them, and their eventual attempts to copy them were what finally gave them the strength to destroy them.

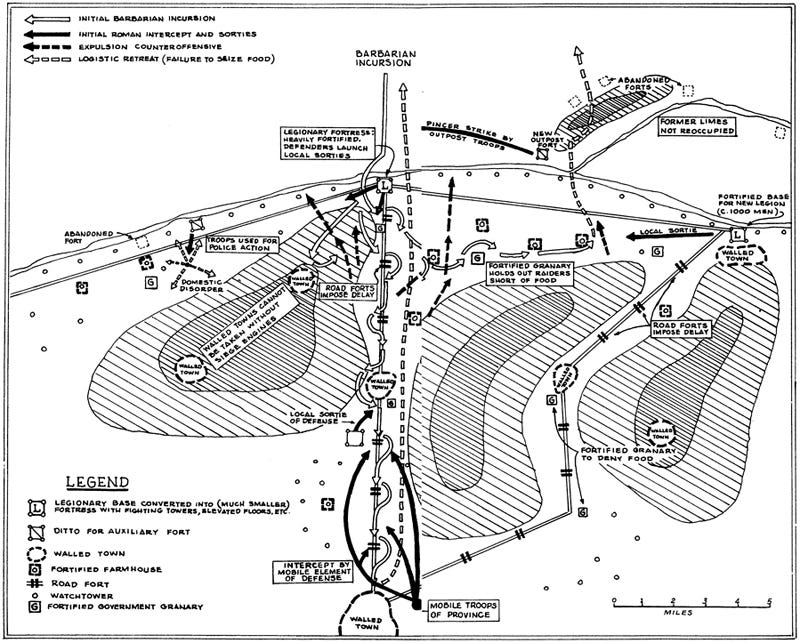

Anyway, the barbarians got stronger and the Romans got weaker, and between the two it was no longer possible to mount a preclusive defense. So the Romans adapted, and began using their fortification line differently. Instead of a springboard for attacks into enemy territory, both it and the dozens of miles of settled land behind it became a shock-absorber for enemy invasions. The strategy broadly resembled a “defense-in-depth,” where the line is expected to be breached but isolated hardpoints are designed to hold out for significant time even if surrounded. Then the enemy is stuck with a dilemma: either sit around reducing these fortifications and giving the defender time to maneuver to respond, or charge ahead with hostile citadels now in their rear, threatening their supply and cutting off their avenues of retreat. This is a strategy that still uses static fortification, but it uses them extremely differently from the second period, and Luttwak accordingly tracks the changes in their design and architecture. Defensibility becomes paramount, both for military camps and for ordinary towns. The walls get thicker, the wells get deeper, low-lying settlements are abandoned, and you start seeing the precursors of medieval castles.

The trouble with defense-in-depth, and with the even more extreme version called “elastic defense,” is that you’re planning for the invader to roll over the initial defense line and to ravage territory dozens or even hundreds of miles behind the border. But all of that destruction is now hitting your primary tax base, and it can take decades for the lands in question to recover. The strategy is an exceedingly efficient use of dwindling military resources, and enables defending against deadly threats with a small outlay of power, but each time it’s employed the empire becomes a little weaker, the next invasion a little harder. Worst of all: it changes the calculation for all the loyal Roman or quasi-Roman inhabitants of the provinces. For a provincial elite, the first two phases discussed here are a good bargain: you give up a little bit of taxation and some population, but in exchange you get peace, security, and trade. Once your lands are being sacrificed as part of a defense-in-depth strategy, the deal looks a whole lot worse. Previously loyal regions may start opting out of imperial structures, raising their own armies, or worst of all striking deals with the invaders. Finally this becomes a self-reinforcing cycle, and the whole system collapses.

What lessons can we draw from this book for today? There are many, but I will leave you with one. Reading about the Roman client state system gave me an uncomfortably familiar feeling. Can we think of another empire that outsources governance to vestigial polities that pretend to be sovereign, and even get called “allies,” but are actually clients? An easy example is the Warsaw Pact. A more controversial one is present-day America and her dependencies. Consider Canada: a normie friend of mine once remarked that Canada pretended to be an independent country, but that if the present world were translated into a computer strategy game its territory would be shaded in the same color as America’s. Indeed, Canada’s sovereignty is exceedingly virtual — it exists only so long as it isn’t tested, just like the sovereignty of a Roman client. Canada is self-governing and self-administering, it passes its own laws and collects its own taxes. But if its foreign policy objectives ever diverged one micrometer from America’s, then Canada would cease to exist. Seriously, imagine Canada offering to host a Chinese or Russian military base and what would immediately occur. There is a real sense in which America rules the land that we know as “Canada,” but has outsourced governance to local elites in a highly federalized structure.

Luttwak has a charmingly racist bit about how some client states have the IQ and sophistication to understand the true nature of the arrangement, while others are too dumb or barbaric to remember who’s boss without having their faces regularly rubbed in it. In the Roman case, the former camp contained the various Hellenistic kingdoms in Asia Minor and the Levant, who didn’t need legionaries standing around and supervising them, because they could imagine the existence of those legionaries and what they would do to them if provoked. The latter camp included many of the Germanic tribes, who tended to forget their place if the legions weren’t garrisoned within eyeshot, and even then would rise up in fruitless rebellion every couple of generations. We can make this marginally less racist by positing something more like a spectrum of how tolerable the client arrangement was, and consequently a spectrum of how coercive it had to be. The Greeks were relatively compatible culturally with the Romans, and the warrior spirit of their ancestors had been sufficiently sanded down that they didn’t mind being told what to do. The Germans were more foreign, and also retained the barbarian’s yearning for freedom, so a careful eye had to be kept on them.

A true cynic might think that there was something similar going on with America’s imperial dependencies…sorry, with America’s “allies.” There are no American garrisons in Canada, because the Canadians are culturally-compatible, and also because they’ve been throughly cowed and do not dream of an independent national destiny. But look overseas, for instance at some of our Middle Eastern “allies,” and you will see a situation more analogous to the Germanic tribes. What a coincidence that these same “allies” host a much heavier American military presence! Even here, however, the situation isn’t strictly coercive, and insofar as it is, the coercion is mostly outsourced to local elites. Those elites, in turn, can mostly be handled with carrots: the imperial power subsidizes their trade and security arrangements, not to mention keeps them in charge of their respective countries! The Romans commonly rewarded loyal clients with citizenship and a cushy sinecure for a job well done. It would be rude of us to do otherwise.

Maybe this was already obvious to everyone else, but reading the “rules-based international order”9 as a concealed hegemon/client system feels a bit like having the skeleton key to understanding current events. Like why do European countries so often act in ways contrary to their own economic or geopolitical self-interest, but consonant with America’s interest? How do the political and business elites of these countries maintain such an impressive unified front in the face of popular discontent? Why do the rulers of all these very different countries have seemingly identical tastes, worldviews, and mannerisms? What is the meaning of “populism,” and why do people treat it like it’s a single, consistent thing, despite the fact that “populist” parties in different countries often seek diametrically opposite policies?

Just pretend, imagine with me, that these European “allies” are client kingdoms. They are permitted a certain amount of latitude, but when the chips are down they do not have an independent foreign policy. Their ruling classes are client rulers that administer certain territories, and there is tacit agreement with the imperial overlord on what they may and may not do. Over time, the client rulers identify less and less with their countrymen, more and more with their counterparts in other client states, and most of all with the distant metropole, whose social approval they desperately desire. The “populists” are simply the anti-imperial party, in whatever country. The thing the “populists” have in common is a desire to be free of the suffocating imperial embrace,10 but they all have a thousand different stupid ideas about what to do with that freedom. This includes the “populists” in the United States itself, by the way. The American Empire is called that because it started here, but it has long-since burst free of the host in which it incubated, and the rot of our own political institutions can be understood as our transformation into the biggest client kingdom of them all.

None of what I’ve said above is meant to be a value judgement. I think many people resist the notion that America is an empire because empires are “bad” and we’re obviously the good guys. But others, including myself not too long ago, resist it because we have an overly-simplistic notion of what an empire looks like, especially what it looks like from the inside. Empires exist on a spectrum — America’s subjects certainly have more ability to act independently than Rome’s did. But many empires also go to some lengths to conceal their true nature. Around the time of the birth of Christ, the official story in many of the lands ruled by Rome was that Rome was merely their largest trading partner and a staunch military ally. Some of them might even have believed it.

Evidence that it’s false, he tells a completely different story in a different interview!

I chose the subject because no theme in contemporary strategy was anywhere as interesting as the simple question of how Rome defended its territories (and added to them, now and then). Also, I did not want to waste my days reading the stultified & chaotically duplicative literature of “political science” in which Strategy is imprisoned, when I could read instead in the often elegant, multi-lingual literature of Roman imperial studies.

The zoomed-out, autistic alien robot anthropologist nature of this analysis also reminds me a bit of Vaclav Smil.

Wouldn’t the most elegant use of power be its deployment in such a way that it doesn’t really have to be used at all? In fact this is the main theme of Luttwak’s most recent book, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, a sort of sequel to this one. In the same interview as in the first footnote, Luttwak summarizes the argument of that book: Byzantine strategy was based on:

a single, paradoxical, principle: do everything possible to raise, equip and train the best possible army and navy, and then… do everything possible to use them as little as possible... every alternative was to be tried to avoid, or at least minimize the destructive “attrition” combat of main forces. Instead, potential enemies were to be dissuaded, bribed, subverted, weakened by getting others to attack them, sidetracked into other ventures; if enemy forces attacked nonetheless, they were to be contained and delayed by skirmishing, feints and demonstrations while the search went on for other powers near or far willing to attack or at least threaten the enemy power; if enemy attacks persisted nonetheless, they were to be met by countering maneuvers designed to exhaust them rather than the destructive combat of main forces, the very last resort. It was not only the precious trained manpower of the empire that this strategy wanted to conserve, but also the enemy’s… because today’s enemy could become tomorrow’s ally.

This isn’t quite true in every period. For instance during the Punic Wars, the Romans fielded “equites,” native Roman cavalry of their own, but it fell out of fashion pretty quickly thereafter.

This is actually also true of modern wars, and if you think you have an exception in mind, you may just not know the history that well. For instance, the current war in the Donbass wasn’t really a surprise invasion, but is best viewed as the latest and most violent stage of a conflict that’s been slowly ratcheting up for a decade.

Were you ever confused by who exactly this King Herod guy in the Gospel stories was? Why was there a king and also a Roman governor? He was precisely one of these client rulers!

Pronounced “lee-mays,” not like the fruit.

I, an ignoramus, assumed this was all downstream of the Maginot line’s bad reputation, but Luttwak says it’s actually the fault of Clausewitz.

The rules-based international order which has no rules, isn’t based, and opposes order.

They may also have in common the payments made to their bank accounts by the empire’s enemies.

"Seriously, imagine Canada offering to host a Chinese or Russian military base and what would immediately occur."

That's a good question, and I think people who say "the USA immediately invades Canada" possibly haven't thought that through well enough. That isn't to say it wouldn't be on the table with any level of certainty, but that would be a much larger step than I think most people grasp.

When applying the Roman Empire model to the US hegemony, it is also worth noting the differences in the direction of resource flow. The US does not seem to collect any tribute from its "client states", and if anything subsidizes them, which is a stark difference from the Roman model. Now possibly that is because the resources are less exciting than the political backing, but then again, Europe doesn't do much to provide military support. Land for bases, sure, but not a lot of auxiliaries.

In all, the modern US hegemony seems like akin to the Roman Empire's model than the model of a celebrity entourage: lots of hangers on who don't seem to contribute much other than "friends" and a group to hang out with, and possibly connections and a couch to crash on now and again. The older, Cold War era model probably was a bit closer to the Roman model, but even then it is a bit questionable. A new paradigm, with some features carried over, might be necessary.

Great review again, much appreciated!

I find Bret Devereux's writing about the "Status Quo Coalition" [1] to be more optimistic and more convincing. In particular, the economics of warfare have changed drastically (no longer is agricultural land the basis of wealth), so a direct analogy between the Roman empire and present day seems very crude. Devereux knows enough not to make that mistake.

It's true that if you squint, it's a little bit comparable. In modern times, most countries know that wars of conquest are unprofitable, but not all. This might be sort of like the calculation Roman "allies" made.

But not really the same. You might, for example, notice that many countries actually do have their own foreign policies, substantial disagreements with the US, and don't pay taxes to the US.

[1] https://acoup.blog/2023/07/07/collections-the-status-quo-coalition/