GUEST REVIEW: Letter to the Soviet Leaders, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Please enjoy another guest review while our baby learns to sleep. This time we present one by “Reginald Saki”, a policy analyst who advises the United States government.

Letter to the Soviet Leaders, Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn (Harper Row, 1975).

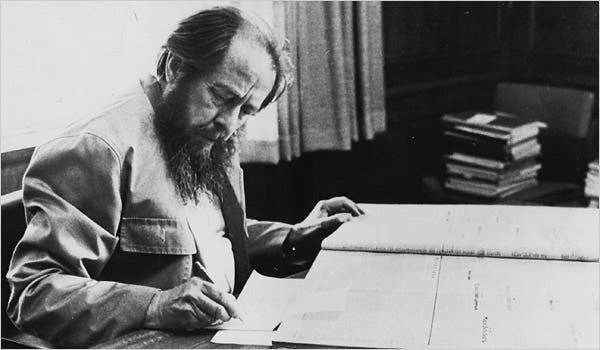

Shortly before he was expelled from the Soviet Union on February 13, 1974, Alexander Solzhenitsyn did something strange. The famed novelist and political dissident dropped into the mail a sixty-page letter, addressed to the Soviet leadership, giving his frank opinions on where the country was headed and advising them on what they should do to survive the coming times of trouble.

It’s hard to overemphasize what a weird thing this was to do. At the time Solzhenitsyn was writing, the USSR was ruled by a group of sclerotic bureaucrats who were officially motivated by a Marxist ideology that no serious person could believe. But while no one really believed in the government, you certainly weren’t allowed to criticize it. They put you in jail for stuff like that. Solzhenitsyn had spent years in the Soviet prison system after writing critical comments about Stalin in a private letter. After he got out, he was briefly fêted as a prison writer during an anti-Stalin thaw. But he soon fell out of favor again and was subjected to increasing surveillance and harassment, possibly including at least one attempted assassination.

By the time Solzhenitsyn wrote his Letter, the Soviet elite viewed him as something close to Public Enemy Number One. His writings exposing the crimes and follies of the Soviet regime, most famously The Gulag Archipelago, indicted the system every bit as powerfully as the 1619 Project does the American Founding (and with the added advantage of being accurate). Indeed, Solzhenitsyn was viewed as such a great threat to the Soviet system that shortly after he sent his letter (and before it was formally published), the Soviet leaders expelled him from the country. The closest equivalent in our own society to how Solzhenitsyn was viewed by the Powers That Were would be a white supremacist school shooter with a manifesto, or possibly Ted Kaczynski.

All of this is to say that Brezhnev and Co. were not very likely to follow the suggestions Solzhenitsyn made in his letter, whatever they were. And Solzhenitsyn knew this. He was not a stupid man. He was not naïve about the Soviet regime, or the nature of power. So what was he thinking?

It’s tempting to assume that in writing Letter to the Soviet Leaders Solzhenitsyn was following the formula of writers of open letters everywhere and that his real audience was someone else. Supporting the interpretation is the fact that, after being expelled to the West, Solzhenitsyn had the Letter published publicly.

But there are also reasons to think that he was serious. Solzhenitsyn wrote in his diary about the Letter that while his “proposals, of course, were sent with only the smallest grain of hope” that they would be heeded, there was nevertheless “still a grain.” What was that grain? Solzhenitsyn may have been a proscribed citizen of a totalitarian dictatorship, but he had one thing going for him — something that even you, dear reader, most probably do not have. Have you ever written a sixty page letter to your head of government detailing your views on how to right the ship of state? What would happen if you did? What are the odds that your ideas would be discussed in the next cabinet meeting? Zero, of course. If you are lucky, you would receive a nice form letter (with a stamped-on signature) thanking you for your input.

Unlike you, Solzhenitsyn was actively hated by his government. Unlike you, Solzhenitsyn did not live in a democracy, where he was (in theory) “the boss” and had a right to petition his government for redress of grievances. But also unlike you, Solzhenitsyn was a famous writer and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Solzhenitsyn knew that if the Soviet leadership did not personally read his Letter, they would at least have its contents summarized for them. They would know. By sending his Letter, Solzhenitsyn put the Soviet leadership on notice; by publishing it, he put himself on record.

In addition, Solzhenitsyn appears to have shaped the content of the Letter to be more palatable to the Soviet leadership. The Letter is remarkably free of anything that could be considered moralizing. It’s clear from Solzhenitsyn’s other writings that he wasn’t averse to detailing the moral crimes of Soviet communism. But here he takes care to frame his arguments in terms of cold realism rather than moral appeals. There is a lot of discussion in the letter, for example, about the threat of war with China, and Solzhenitsyn frames his proposed reforms as necessary to deal with this threat. China was not a subject that Solzhenitsyn seems to have cared much about based on his writings before and after the letter. But it was a subject that the Politburo cared quite a lot about in the early 1970s, and Solzhenitsyn knew his audience.

Solzhenitsyn also tried to limit his recommendations to things that could theoretically be granted by the then-existing government. Much of the first half of the letter almost resembles a policy paper, with proposals on such things as agricultural policy, gender quotas, and vodka. And even when he gets to his Big Ask — abandon Marxism, cease all efforts to spread or maintain Communism internationally, let the non-Russian republics leave the USSR — he doesn’t make the one demand that liberal western audiences would have considered essential. He isn’t asking the Soviet leaders to give up power. He doesn’t demand democracy, real elections, or a Western style of government: “It is not authoritarianism itself that is intolerable but the ideological lies that are daily foisted upon us.” Indeed, the Letter highlights the lack of his demand as a selling point, saying in effect that the current leadership could keep their jobs: following his recommendations is the way for the Soviet leaders to retain power. “You will still have absolute and impregnable power, a separate, strong and exclusive Party, the army, the police force, industry, transportation, communications, mineral wealth, a monopoly on foreign trade, an artificial rate of exchange for the ruble – but let the people breathe, let them think and develop!”

It can be difficult to tell what in the Letter represents Solzhenitsyn’s full, unvarnished views as opposed to what has been tailored to appeal specifically to the Soviet leaders. When a pundit sits down to write his latest column, or a think tanker to write his newest white paper, he must decide how far to go in advocating his political ideal — and how much to trim his ideal to the political realities of the time. If he says how he thinks things should be ideally, he will often end up with fantasy. It might be an enjoyable read, but it won’t have any effect on the course of events.

At the same time, though, there is a risk in making one’s proposals too realistic. When a public figure advocates for the government to do X, he is implicitly abandoning any push to have it do something greater than X (at least for the time being). Just as in a negotiation it is prudent to ask for more than you need so you don’t end up with less than you can stand, it can also make sense for policy proposals to err on the side of ambition. When a public figure offers advice, people sometimes draw the (wrong) conclusion that his ultimate aims are more modest than they really are. Often, writing of this kind ends up in a grey middle area: the proposal is far less than what the writer really wants, but still too ambitious to have any hope of actually happening.

The original audience of the letter may have been the Soviet leaders themselves, but when Solzhenitsyn chose to publish the letter it gained a new audience, and one that was perhaps not prepared to understand it. It’s fair to say that Solzhenitsyn’s letter caused a fair amount of confusion and even hostility in the West when it was published. Not for the last time, he was accused of being anti-democracy, anti-liberal, and anti-freedom.

These charges were unfair, but they also weren’t entirely off base. Of course, Solzhenitsyn wasn’t against democracy per se: in his memoir Between Two Millstones (written less than a year after the Letter), he movingly and approvingly describes the democratic deliberations of a Swiss canton. Solzhenitsyn did think that politics in democracies often tended to be venal and election campaigns superficial, but most citizens of democracies feel the same way.

On the other hand, Solzhenitsyn did not believe that democracy was workable in Russian society as it then existed. Imagine a genie had appeared to a typical liberal circa 1974 and told him he could change one thing about the Soviet system. For most liberals, the answer would have been “add democracy”: allow for free and fair elections, and the rest of the nation’s problems would be sorted out. Solzhenitsyn, by contrast, would have said “remove Marxism.” Changing the ideological basis of the system would allow the country to address its problems in an orderly manner, whereas an abrupt shift to democracy would be unstable and would ultimately collapse back in on itself.

Solzhenitsyn’s views on this score had been influenced by his study of the Russian Revolution. In the popular Western imagination, the Russian Revolution is a unified event in which the Czar is overthrown and replaced by a new Communist regime. In reality, though, there were at least two different revolutions in Russia in 1917. In the February Revolution, the Czar was forced to abdicate and was replaced by a liberal provisional government. The Bolsheviks played almost no role in this revolution, and in fact their leader, Vladimir Lenin, was hiding in Switzerland at the time and only found out what had happened after the fact. It was not until October that the provisional government was itself overthrown and the Bolsheviks took power.

You might think that Solzhenitsyn would have favored the February Revolution and wished only that it had not been replaced by the Communists. But you would be wrong: Solzhenitsyn thought the February Revolution’s introduction of democracy had been profoundly destabilizing, and its destruction of the pre-existing order had actually helped to usher in the totalitarian October Revolution.

Further, he reasoned that if Russia had not been ready for an abrupt shift to democracy in 1917, it was even less prepared to do this after two generations of Communism. All the indoctrination and mindless deference to bureaucratic authority, along with the atrophy of religion and civil society, meant that the Russian people lacked the habits and character needed to make democracy work. As he says, “I am inclined to think that [democracy’s] sudden reintroduction now would merely be a melancholy repetition of 1917.”

To a modern American, the idea that some people are not suited to democracy smells of heresy. John Adams may have said that America’s institutions “were fit only for a moral and religious people,” but we no longer believe that. We tend to overlook the fact that democracy grew up slowly first in Britain and then in the American colonies, and that full suffrage wasn’t embraced in either theory or practice until well into the history of the United States. We tend to think that, with the assistance of some NGOs and a well placed cruise missile or two, any country can make democracy work. Throughout our history, America has periodically tried to spread democracy to other parts of the world, often through force of arms. Sometimes it has worked out. Other times it hasn’t.

Solzhenitsyn was often presented as a kind of Old Testament prophet. Like most prophets, his words were ignored. The Soviet leadership to whom his Letter was addressed did not heed his words and continued along the path they had set for themselves. Less than twenty years later they were gone and the country they had governed had ceased to exist. Russia made the transition to democracy, throwing off Marxism in the process. In 1994, Solzhenitsyn was able to return from exile.

So on one level, Solzhenitsyn could claim vindication. He had predicted that if the Soviet leaders did not listen to him, they would lose power. They did not listen. They lost power. QED.

On the other hand, from the standpoint of the early nineties, the specific thrust of Solzhenitsyn’s Letter did not seem to have aged very well. After all, suppose that Brezhnev and his successors had followed his recommendations to change the USSR into a non-Marxist but still authoritarian regime. And suppose that this had in fact allowed the regime to survive. In that case, the Russian people would still be suffering under tyranny, and without any realistic near term hope of moving to a democratic system. You might even say that it was lucky that the Soviets hadn’t listened to Solzhenitsyn.

History, however, does not always follow a straight path, and fifty years after the Letter, the situation looks more complicated. While the end of Soviet rule undoubtedly had its advantages (especially for the captive peoples of what was then called “Eastern Europe”), the transition was brutal. Between 1991 and 1996, GDP in Russia fell by 37%. The situation in some of the other former Soviet republics was even more bleak. GDP in Ukraine fell by 53% between 1991 and 1996, and even as of 2015 GDP remained at 63% of its 1991 level. Inflation ran rampant, and social services were cut. Some of this was no doubt due to the economic contradictions of the Marxist command economy, but the results did not remain in the realm of abstract economic statistics. Life expectancy in Russia fell from 69.46 years in 1988 to 64.47 years in 1994.

The introduction of real democracy into Russia unleashed some powerful illiberal forces. The ironically named Liberal Democratic party, led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky, came to prominence promoting ultranationalism and right wing populism. Zhirinovsky advocated a return to Russia not only of all the post-Soviet republics, but also territories belonging to Russia prior to the First World War, including Finland and Poland. A reorganized Communist Party also seemed to be gaining renewed appeal. Not for the first time in history, liberal elites began to fear the anti-democratic impulses of voters.

As it turned out, though, the actual destruction of democracy came from a different direction. Many people remember Boris Yeltsin standing on a tank outside the Russian parliament building in defiance of a coup attempt in 1991. Fewer people remember that Yeltsin himself had the parliament building shelled in 1993 after illegally dissolving the legislature and ruling by decree. Facing a daunting re-election bid with a single digit approval rating, in 1996 Yeltsin struck a deal with a group of powerful business leaders to gain their support in return for special favors and influence. The security services also began to play a more prominent role in public life. On the eve of the new millennium, Yeltsin announced that he would be stepping down in favor of former KGB agent and recently appointed prime minister, Vladimir Putin.

Over the course of the next decade, Russia evolved away from democracy and into exactly the sort of non-ideological autocracy that Solzhenitsyn anticipated in his Letter. In fact Putin admired Solzhenitsyn and met with the then elderly author shortly after assuming the presidency, though there is no evidence that he ever read the Letter let alone that he viewed it as some sort of roadmap.

Americans have been thinking a lot more about Russia is recent years. In part this is due to its invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing conflict there. Russia has also played a prominent role in our domestic politics, where the U.S. intelligence services have used claims of Russian interference, and the threat to democracy this represents, to undermine various populist and nationalist political figures. Many people in the West, including in high positions of power, would like to see Vladimir Putin overthrown. But there is little reason to think that Russia would fare any better if given a third chance at democracy than it did during its prior two occurrences. Indeed, many of Putin’s fiercest critics within Russia come not from liberals but from the ultranationalist right, who blame him for not being aggressive enough in Ukraine and in promoting Russian national greatness.

Across the political spectrum, American policymakers still seem stuck in a Cold War mindset where Russia stands for communist aggression. But Russia has long since abandoned Marxism: the intolerable “ideological lies” simply could not stand forever, and neither could an alien and inapplicable Western-style democracy. Like a rubber band snapping back to its true shape the moment you let go, Russia has once again returned to the centralized autocracy it has mostly been since the 16th century, paranoid and defensive, with territorial ambitions that are revanchist rather than expansionist in nature.

The fact that official doctrine and underlying structure can move independently may not seem intuitive, especially to Americans who like to imagine that ours is a government of checks and balances because it is uniquely animated by the democratic spirit of the Founding. But our system has also had its transformations: the rise of the administrative state, for instance, was a profound shift in internal logic that preserved the outward forms of the republic. And it goes the other way, too: the official ideology can shift while the machinery of the state grinds on much as it ever has — and that’s when you risk developing your own “ideological lies.” Many Americans have felt disoriented by the way our own regime’s official pieties and dogmas have shifted under our feet over the past decade. How long, they ask, can these lies survive? The answer the Soviet Union teaches us is: lies can survive a long time, perhaps longer than you can survive, but not forever.

And so today the closing words of Solzhenitsyn’s Letter work eerily well as a warning to the American elite, just as they once did to the apparatchiks for whom he wrote them: “Your dearest wish is for our state structure and our ideological system never to change, to remain as they are for centuries. But history is not like that. Every system either finds a way to develop or else collapses.” What might that development look like in our case? The optimistic case looks like the fall of the Soviet Union: an end to an unnatural external imposition and a reversion to the historic norm which for us, unlike Russia, is actually democratic. But that assumes that America remains what it once was: a high-trust commercial republic of merchants and gentleman farmers. The pessimistic case is that we now look more like the historical Russia: with an indigestible ethnic patchwork, alienated urban proletariat, and stagnant rural poverty. A people fit only for despotism.

> "...Alexander Solzhenitsyn did something strange. The famed novelist and political dissident dropped into the mail a sixty-page letter, addressed to the Soviet leadership... It’s hard to overemphasize what a weird thing this was to do... But while no one really believed in the government, you certainly weren’t allowed to criticize it."

Letter writing was actually a big part of Soviet political culture. If you ever have to comb through Soviet primary sources, letters to the government or responses from the government make up a significant portion of primary source documents telling us about daily life in the Soviet Union.

Obviously, you had to be careful of what you said in a letter, but in a nation where demonstrations and protests were tightly cracked down upon, private letters to the government were a way for citizen to vent their frustrations or speak to people in their government. The Soviets cared a lot about what people said publicly, they cared a lot less about what people said privately to the government.

While you couldn't exactly send a letter like Solzhenitsyn's, you could send a strongly worded letter critical of the government. The KGB actually relied heavily on letters to gauge public sentiments because letters provided information directly from the population, rather than having that information filtered through numerous layers of bureaucracy.

Overall, enjoyable piece, but letter writing was not out of the ordinary in the Soviet Union.

> While the end of Soviet rule undoubtedly had its advantages (especially for the captive peoples of what was then called “Eastern Europe”), the transition was brutal. Between 1991 and 1996, GDP in Russia fell by 37%. The situation in some of the other former Soviet republics was even more bleak. GDP in Ukraine fell by 53% between 1991 and 1996, and even as of 2015 GDP remained at 63% of its 1991 level.

Then again USSR GDP statistics aren't the most credible.