REVIEW: The Longing for Total Revolution, by Bernard Yack

The Longing for Total Revolution: Philosophic Sources of Social Discontent from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsche, Bernard Yack (Princeton University Press, 1986).

This is a book by Bernard Yack. Who is Bernard Yack? Yack is fun, because for a mild-mannered liberal Canadian political theorist he’s dropped some dank truth-bombs over the years. For example, check out his short and punchy 2001 journal article “Popular Sovereignty and Nationalism” if you need a passive-aggressive gift for the democratic peace theorist in your life.1 The subject of that essay is unrelated to the subject of the book I’m reviewing, but the approach, the method, and the vibe are similar. The general Yack formula is to take some big trendy topic (like “nationalism”) and examine its deep philosophical and intellectual substructure while totally refusing to consider material conditions. He’s kind of like the anti-Marx — in Yack’s world not only do ideas have consequences, they’re about the only things that do. Even when this is unconvincing, it’s usually very interesting.

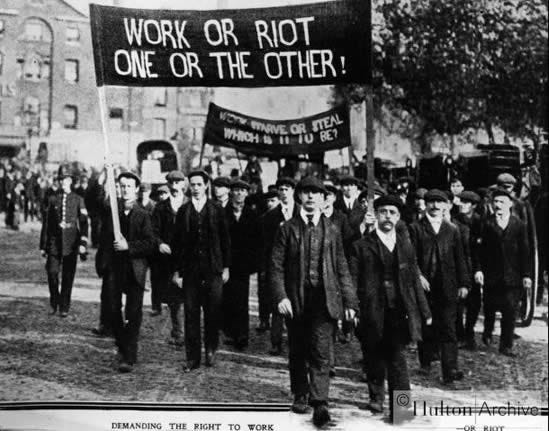

The topic of this book is radicalism in the ur-sense of “a desire to get to the root.” What Yack finds interesting about radicalism is that it’s so new. It’s a surprising fact that the entire idea of having a revolution, of burning down society and starting again with radically different institutions, was seemingly unthinkable until a certain point in history. It’s like nobody on planet Earth had the idea, and then suddenly sometime in the 17th or 18th century a switch flips and it’s all anybody is talking about. We’re used to that sort of pattern for scientific discoveries, or for very original ways of thinking about the universe, but “let’s destroy all of this and try again” isn’t an incredibly complex or sophisticated thought, so why did it take so many millennia for somebody to have it?

Well, first of all, is this claim even true? One thing you do see a lot of in premodern history is peasant rebellions, but dig a little deeper into any of them and the first thing you notice is that (sorry vulgar Marxists)2 there’s nothing especially “revolutionary” in any of these conflagrations. The most common cause of rebellion is some particular outrage, and the goal of the rebellion is generally the amelioration of that outrage, not the wholesale reordering of society as such. The next most common cause of rebellions is a bandit leader who is some variety of total psycho and gets really out of control. But again, prior to the dawn of the modern era, these psychos led movements that were remarkably undertheorized. The goal was sometimes for the psycho to become the new king, sometimes the extinguishment of all life on earth, but you hardly ever saw a manifesto demanding the end of kings as such. Again, this is weird, right? Is it really such a difficult conceptual leap to make?

Peasant rebellions are demotic movements, but modern revolutions are usually led by frustrated intellectuals and other surplus elites. When elites did get involved in pre-modern rebellions, their goals were still fairly narrow, like those of the peasants — sometimes they wanted to slightly weaken the power of the king, other times they wanted to replace the king with his cousin. But again this is just totally different in kind from the 18th century onwards, when intellectuals and nobles are spending practically all of their time sitting around in salons and cafés, debating whose plan for the total overhaul of society, morality, and economic relations is best.

The closest you get to this sort of thing is the tradition of Utopian literature, from Plato’s Republic to Thomas More, but what’s striking about this stuff is how much ironic distance it carried — nobody ever plotted terrorism to put Plato’s or More’s theories into practice. Nobody ever got really angry or excited about it. But skip forward to the radical theorizing of a Rousseau or a Marx or a Bakunin, and suddenly people are making plans to bomb schools because it might bring the Revolution five minutes closer. So what changed?

Well this is a Bernard Yack book, so the answer definitely isn’t the printing press. It also isn’t secularization, the Black Death, urbanization, the Reformation, the rise of industrial capitalism, the demographic transition, or any of the dozens of other massive material changes that various people have conjectured as the cause of radical political ferment. Instead Yack points to two abstract philosophical premises: the first is a belief in the possibility of “dehumanization,” the idea that one can be a human being and yet be living a less than human life. The second is “historicism” in the sense of a belief that different historical eras have fundamentally different modes of social interaction.

Both views had some historical precedent (for instance historicism is clearly evident in the writings of Machiavelli and Montesquieu), but it’s their combination that’s particularly explosive, and Rousseau is the first person to place the two elements together and thereby assemble a bomb. Because for Rousseau, unlike for any of the ancient or medieval philosophers, merely to be a member of the human species does not automatically mean you’re living a fully-human life. But if humanity is something you can grow into, then it’s also something that you can be prevented from growing into. Thus: “that I am not a better person becomes for Rousseau a grievance against the political order. Modern institutions have deformed me. They have made me the weak and miserable creature that I am.”

But what if the qualities of social interaction which have this dehumanizing effect are inextricably bound up with the dominant spirit of the age? In that case, it might be impossible to really live, impossible to produce happy and well-adjusted human beings, without a total overhaul of society and all of its institutions. This also clarifies how the longing for total revolution is distinct from utopianism — utopian literature is motivated by a vision of a better or more just order. Revolutionary longing springs from a hatred of existing institutions and what they’ve done to us. This is an important difference, because hate is a much more powerful motivator than hope. In fact Yack goes so far as to say (in a wonderfully dark passage) that the key action of philosophers and intellectuals upon history is the invention of new things to hate. Can you believe this guy is Canadian?

The bulk of the book is an intellectual history of these two new intellectual premises, and the ways they contribute to a longing for total revolution in the works of a dozen or so European philosophers. Most of the emphasis is on Rousseau, and then on the German disciples of Kant and Hegel. Obviously the elephants in the room here are the French Revolution and the various communist revolutions of the 20th century, but those events remain very much in the background, apart from their influence on the writing and thoughts of a handful of German idealists. Remember, this is a book by Yack, so ideas, not people, are the protagonists, the only true wheels that move history.

Yack makes Rousseau sound a lot more fun than the mainstream picture of him. Before this my main exposure to Rousseau was via 20th century libertarian thinkers like Nisbet, Hayek, and de Jouvenal, for whom he is a bête noire and the father of communism. And he totally is the father of communism, but in a much more interesting way than they realize. The knock on Rousseau is that he believed in using the absolute despotic power of the state to “free” people from the petty oppressions of family, tribe, and community. But that’s a distortion — the freedom Rousseau sought, the measure of full humanity, was freedom from inner conflict. Rousseau admired the Spartans for the way they subsumed their individuality into the totalizing world of the polis. So there’s an alternative reading of Rousseau in which he’s also the father of fascism.

On the other hand, before reading this book I mainly knew Kant through his metaphysics and epistemology, and so I hadn’t quite realized just how unbelievably schaudern und Aufklarung gepillt he is. Kant is like the 18th century version of the boomer who spends his life dynamiting the foundations of his civilization and then is shocked, shocked to discover that the young people want a revolution. This was also my first encounter with Kant’s work on Perpetual Peace, which is a clear precursor to the democratic peace theory I made fun of at the start of this review — a little better because he has the excuse of not having seen how the next few centuries turned out, a little worse because the whole thing is just intolerably Reddit. After Kant we get a succession of German guys that I don’t really care about, because I’m a total philistine when it comes to modern philosophy (if you’re interested in learning more about them, I recommend this educational video)3. But then we get to the good stuff, and by the good stuff I mean Marx and Nietzsche.

With Marx, dehumanization takes the form of alienation of workers from their productive powers. I’d always thought this was a bit of an aside from the main thrust of Marxism, or a post-hoc justification for what Marx wants to do anyway, but Yack argues convincingly that fear of alienation is the driving force behind all of Marx’s thinking. Long before Marx came up with his economic theories about the immiseration of the proletariat, he was already describing the commodification of labor as ipso facto dehumanizing, and comparing the workers selling “control and conscious direction” of their labor power to Esau selling his birthright for a mess of pottage. Since the buying and selling of labor power is intrinsic to capitalism, Marx comes to hate capitalism and to long for its overthrow. All the theories of proletarian revolution, and the entire positive case for communism itself, are downstream of concerns with alienation and dehumanization, not vice versa.

Why does the buying and selling of labor arouse such fury in Marx, so much so that tearing down the institutions that necessitate it became his whole life’s mission? Well have you ever really worked? Have you worked so hard that you came to the end of your day beaten and defeated and with no thought for anything but the sweet oblivion of sleep, and then woken up the next morning and worked again? There’s something almost transcendent about work. Men were made for work, and without work we become aimless or destructive or just fade away and die. Work is when you face up to the cold void of the universe and decide: “no, not today.” Or as Marx puts it:

In labour, man faces nature as one of her own forces. He sets in motion the natural forces of his body, arms and legs, head and hands, in order to appropriate nature’s productions in a form useful to his own life. While these movements affect and later alter external nature, they change his own nature at the same time.

Work changes man’s nature, but work is also man acting as Nature does. The difference is that the universe is random, whereas man, by channeling and directing Nature’s forces under his conscious control, transmutes them into what Marx calls “form-giving fire.” Marx may claim to be irreligious, but his language is a dead giveaway: this is how people talk about the sacred. And that’s the other reason he objects to markets in labor; Marx thinks selling your labor is like prostitution or simony. I don’t quite agree with him on this, but I get it. Some very important things are not meant to be bought and sold.4

Everybody likes to make fun of the libertarians who claim that taxation is equivalent to slavery, but listen to it again and this is actually a very Marx-inspired slogan. What those libertarians really mean is that taxation forces you to work more to bring home the same pay, and that involuntary work is a kind of slavery. If you work 8 hours a day and pay a 50% tax rate, then 4 hours of your life are being consumed every day. That’s like a quarter of your waking hours, concentrated in the best years of your life. Maybe we’d have more sympathy for this argument if the government extracted those hours from us in kind, by forcing us to work on government-selected projects. Then the rallying cry would be “corvée labor is slavery,” and people might not laugh at it. Certainly the hill peoples who have always resisted state intrusion viewed taxation, work levies, and outright slavery as a spectrum. Anyway, if this argument moves you at all, then you should also be sympathetic to Marx’s anxieties around alienation of labor — your work is your life.

Under conditions of alienation, your work turns into something else though. This passage from Capital sounds like something from Fanged Noumena:

It is now no longer the labourer who employs the means of production, but the means of production that employ the labourer. Instead of being consumed by him as material elements of his productive activity, they consume him as the ferment necessary to their own life-process, and the life-process of capital consists only in its movement as value constantly expanding, constantly multiplying itself.

Or, as Leszek Kolakowski puts it:

the whole of human activity is subordinated to a non-human purpose, the creation of something that man as such cannot assimilate… The whole community is thus enslaved to its own products, abstractions which present themselves to it as an external alien power.

So capitalism is an uncaring alien demigod that gets summoned into being by unsuspecting humans and then possesses them to magnify its power in order to…wait a minute! I’ve heard this music before! He’s saying that capitalism is an egregore! And in fact this concept isn’t limited to Marx and Marxists, it was popularized by a bunch of the original neoreactionaries, and then made the jump into polite society via some of the older and weirder Scott Alexander essays. For the longest time I was bummed that nobody had written a horror story on these themes, but then then some guy produced a very fine one.

Since this book review has come all the way around to the very online right, I’d like to close with something that was in the back of my head the entire time I was reading it. Most of the artists and thinkers surveyed in this book are leftists. They hate aristocracy, hate revealed religion, love equality, love freedom, love the French Revolution, and really fucking love science. This isn’t shocking, right? When we think about the longing for total revolution and the desire to replace all our corrupted institutions, historically that has generally been an impulse of the left. There’s even an entire cottage industry of conservative authors rearranging the furniture in Russell Kirk’s attic and arguing that the revolutionary impulse is inherently leftist because it means giving in to the rationalistic, constructivist impulse and a rejection of the accumulated organic wisdom of the ages.

The problem for this theory is that 100% of the revolutionary energy in our own society is on the right today.5 Yeah, yeah, I know, there are some edgy irony leftists on twitter, and a few people LARPing as communists. But come on, those people always fall in line and do what they’re told. On the other hand, the edgy irony rightists on Twitter seem to genuinely concern the powers that be. Biden even said so. But what’s interesting to me is that these figures aren’t just revolutionary in the sense of desiring the overthrow of contemporary institutions, they’re revolutionary in Yack’s sense too.

The concern that contemporary institutions have inescapably deformed us is at the emotional core of the online right. Beneath all the amoral bluster of the BAP-influenced vitalists is a deeply moral concern that modern civilization is degrading and dehumanizing for all involved. Their favorite terms — like “bugmen” and “yeast life” — all express the horror that society is turning us into something inhuman and unnatural. And it isn’t just the vitalists, the TERF-right, too, is driven by the (correct) fear that something is turning people into degraded and disordered beings. The natalists and the PUAs, despite seeming like polar opposites in most respects, are united by a conviction that the Age of Tinder has destroyed something as fundamentally human as the capacity for pair-bonding. I could keep naming other niches and sub-factions, they all express it differently, they all derive very different prescriptions, but the core concern is shared.

Look beyond the object-level issues, and the resemblance becomes even more stark. Go back to Yack’s two philosophical premises: the belief that there is a human vocation that’s more than just belonging to the human species, and the historicist belief that eras and epochs are defined by a dominant mode of social interaction. The extremely online right, the far right, and the dissident right are some of the few remaining intellectual communities in the West that are still driven by these views, which were once dominant amongst Enlightenment intellectuals and philosophes.

There’s a grand irony here, and a bunch of different theories as to how it happened. Many of them are most un-Yackian — material or social conditions driving ideology, rather than vice versa. For example, Scott Alexander’s barber-pole theory of intellectual fashionability might explain the swap by saying that Yack’s first premise is especially attractive to ambitious people with high human capital, and that while for the past 400 years those people were predominately leftists, today the ratio is flipping and a lot of them are rightists. Alternatively, you could go after the second premise by arguing that historicism is always more attractive to the subaltern, because they’re the ones who seek intellectual liberation by reading about different times and places, whilst the Establishment lives in a mental cul-de-sac analogous to the way New Yorkers think theirs is the only city on earth.

Whatever the case, the flip has happened, and it will only snowball from here. The ideological vanguard of the right longs for total revolution, for the complete dissolution of the corrupted institutions that have made us broken and despicable. For those of us who think revolutions are bad even when well-intentioned, the fact that some of their diagnoses are correct is cold comfort and not at all reassuring.

Of course, if my reading of MITI and the Japanese Miracle is correct, popular sovereignty may not be around for that much longer.

I say “vulgar” Marxists, because for the sophisticated Marxists (including Marx himself) it’s already pretty much dogma that premodern rebellions by immiserated peasants aren’t “revolutionary” in the way they care about.

Kant couldn’t do it. Hegel couldn’t do it. Schelling couldn’t do it. Fichte couldn’t do it. Hölderlin couldn’t do it. Even Donald Trump couldn’t do it. But Bernard Yack is finally going to complete the system of German idealism.

People being people, we usually find ways to buy and sell them anyway. See: Gabriel Rossman’s work on obfuscated exchange.

An interesting related phenomenon is that youth culture is increasingly coded as right-wing by mainstream society. For example, did you know that among people under the age of 25 or so, the word “based” has no political valence whatsoever? It just means “cool”. But for old people like me, “based” sounds very right-wing, just like in the 1970s, “cool” sounded very left-wing. This is because half a century ago, the right was the Mrs. Grundy party, whereas today Mrs. Grundy would obviously be a democrat.

I think the idea that radicalism was invented in the 17th/18th century fails by a strict reading of the claim, but succeeds if you weaken the claim a bit.

I can think of very few, but nonzero radical movements that precede the 17th century, and you definitely wouldn’t call them undertheorized. The Anabaptists of Muenster are 17th century, the Levellers of the English Civil War are 16th century. You’ve got Christianity and Islam (extremely socially radical by any definition), you’ve got Mazdak, a Zoroastrian radical slightly pre-Islam, and then I’m gonna throw Akhenaten in for good measure. I’m sure there are plenty more. Lycurgus of Sparta perhaps.

They all made or wanted sweeping social changes, but the context and driving ideology was exclusively religious. So I think the original claim is false, but can be rescued by appeal to “not exclusively religious radicalism.”

I know that’s not quite the main thrust of the book review, but I think it’s worth pointing out that the radical impulse is definitely not new. To paraphrase Tom Holland, in the ancient world all reforms had to be couched in a fiction of returning to a glorious past (or at least divine approval). Maybe what changed is our lack of need for authoritative validation.

I've been slowly reading all your book reviews. In general very thought provoking. I just wanted to add (the obvious) that the right in the US took over the working class when it was abandoned by the left. And I think Trumps popularity is strong because he remains one of the few political voices that speaks to the working class. Gotta run Saturday is a work day for us cooks. :^)