REVIEW: American Nations, by Colin Woodard

American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, Colin Woodard (Viking, 2011).

We once lived for a few years in another part of the country. It was nice in a lot of ways — I have fond memories of that time, and not just because two of my babies were born there — but periodically I would be suddenly struck by what I can only call a moment of Lovecraft Protagonist: the angles were wrong.

Only obviously it wasn’t really the angles (everything remained relentlessly Euclidean), it was the trees, and the architecture, and the weather, all of which were just a little bit off. And so, more subtly, were the people. Don’t get me wrong, they were all very nice; we’re still in touch with many of our neighbors and church friends from when we lived there. But there were still all these little cultural differences, all the more jarring because they were so slight, and the indefinable sense of comfort when I occasionally ran into someone from “home.”

Of course, the existence of regional cultural differences is not news. Every country has them, and America — with its enormous geographical extent and wide range of newcomers — has more than most. It’s the kind of thing we joke about all the time: Midwesterners who would die before they took the last piece of cake, politely passive-aggressive Southerners (“bless your heart”) and rudely aggressive-aggressive New Yorkers (this is a family Substack so I will omit examples), uptight New Englanders and let-it-all-hang-out Californians. But these stereotyped regional divisions are so vague and underspecified — what is the Midwest, anyway? is Ohio Midwestern? Is Minnesota? Montana? — that they obscure as much as they illuminate. And yet the divisions are there, in laws and voting patterns, in behavior and institutions, in food and music, in dialect and religion and education. You really can tell when someone’s not from around here.

There’s a long tradition of describing the outlines of these regional cultures as they currently exist — Kevin Phillips’ 1969 The Emerging Republican Majority and Joel Garreau’s 1981 The Nine Nations of North America are classics of the genre — but it’s more interesting (and more illuminating) to look at their history. Where did these cultures come from, how did they get where they are, and why are they like that? That’s the approach David Hackett Fisher took in his 1989 classic, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, which traces the history of (you guessed it) four of them, but his attention is mostly on cultural continuity between the British homelands and new American settlements of each group,1 so he limits himself to the Eastern seaboard and ends with the American Revolution.2

Colin Woodard, by contrast, assigned himself the far more ambitious task of tracing the history of all America’s regional cultures, from their various foundings right up to the present, and he does about as good a job as anyone could with a mere 300 pages of text at his disposal: it’s necessarily condensed, but the notes are good and he does provide an excellent “Suggested Reading” essay at the end to point you towards thousands of pages worth of places to look when you inevitably want more of something. Intrigued by the brief discussion of the patchwork of regional cultures across Texas? There’s a book for that! Several, in fact.

Woodard divides the US into eleven distinctive regional cultures, which he calls “nations” because they share a common culture, language, experience, symbols, and values. For the period of earliest settlement this seems fairly uncontroversial — you don’t need to read a lot of American history to pick up on the profound cultural differences between, say, the Massachusetts townships that produced John Adams and the Virginia estates of aristocrats like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, let alone the backwoods shanties where Andrew Jackson grew up. As the number of immigrants increased, though (and this began quite early: several enormous waves of German immigrants meant that by 1755 Pennsylvania no longer had an English majority), it doesn’t seem immediately obvious that the original culture would continue to dominate.

Woodard’s response to this concern is twofold. First, he cites Wilbur Zelinsky’s Doctrine of First Effective Settlement to the effect that “[w]henever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny the initial band of settlers may have been.” (The nation of New Netherland, founded by the Dutch in the area that is now greater New York City, is the paradigmatic example: both Zelinksy and Woodard argue that it has maintained its distinctively tolerant, mercantile, none-too-democratic character despite the fact that only about 0.2% of the population is now of Dutch descent.)3 But his second, and more convincing, approach is just to show you that the people who moved here in 1650 were like that and then in the 1830s their descendants moved there and kept being like that and, hey look, let’s check in on them today — yep, looks like they’re still like that. Even though between 1650 and now plenty of Germans (or Swedes or Italians or whoever) have joined the descendants of those earliest English settlers.

Most of the book is given over to the six nations — Yankeedom, New Netherland, the Midlands, Tidewater, the Deep South, and Greater Appalachia — that populated the original Thirteen Colonies and still occupy most of the country’s area. Told as the story of the distrust or open bloody conflicts between various peoples, American history takes on a ghastly new cast: have you ever heard of the Yankee-Pennamite Wars, fought between Connecticut settlers and bands of Scots-Irish guerillas over control of northern Pennsylvania? Or the brutal Revolution-era backcountry massacres committed not by the Continental Army or the redcoats but by warring groups of Appalachian militias? What about the fact that Pennsylvania’s commitment to the American cause was made possible only by a Congressionally-backed coup d’état that suspended habeas corpus, arrested anyone opposed to the war, made it illegal to speak or write in opposition to its decisions, and confiscated the property of anyone who suspected of disloyalty (if they weren’t executed outright)? Gosh, this is beginning to sound like, well, literally any other multiethnic empire in history. (It also offers some fascinating points of divergence for alternate history.)4

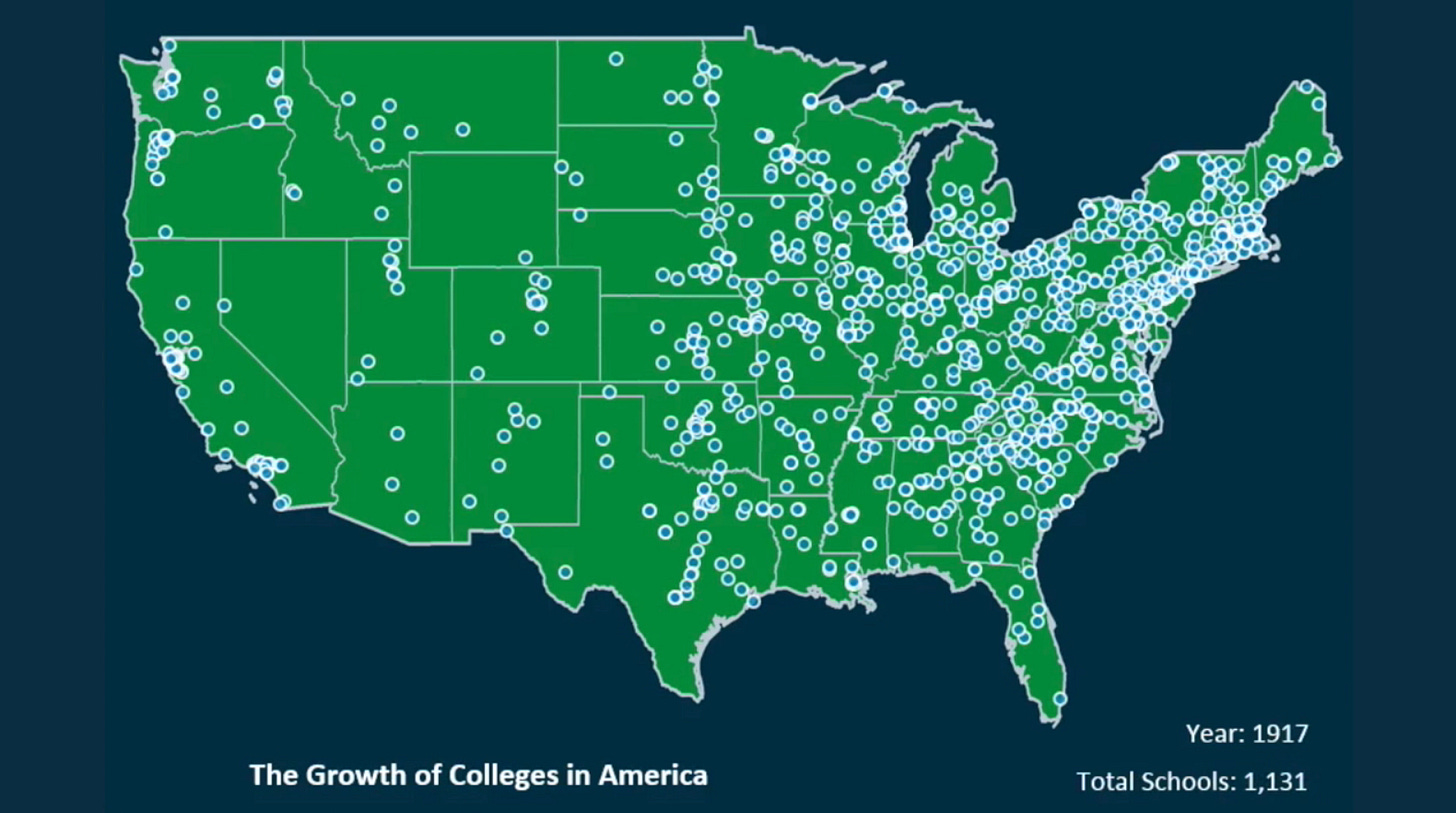

The chapters on westward expansion are some of the most interesting, tracing settlement patterns across the Midwest like one of those maps of the the Migration Period — and where the Yankees settled determined a great deal.5

Nineteenth-century visitors often remarked on the difference between the areas north and south of the old National Road, an early high way that bisected Ohio and is now called U.S. 40. North of the road…[v]illage greens, white church steeples, town hall bellfries, and green-shuttered houses were the norm. South of the road, the farm buildings were unpainted, the people were poorer and less educated, and the better homes were built with brick in greco-Roman style. “As you travel north across Ohio,” Ohio State University dean Harlan Hatcher wrote in 1945, “you feel that you have been transported from Virginia into Connecticut.”

But rather than summarize Woodard’s story — which would be a tall order, because the book is already a tightly condensed synthesis of the work of many others — I’m going to focus on two particular nations: one because it’s nearly gone, and one because it’s everywhere.

The first nation that struck my interest was Tidewater, earliest of the English nations. (El Norte and New France, as Woodard names them, are the remnants of colonial empires that predate English settlement in North America.) Founded on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay by gentlemen from southern England, and with a sizeable population influx a generation later from Royalists who had found themselves on the losing side of the English Civil War, Tidewater began with an aristocratic ethos. Its gentlemen wanted to recreate the rural manor life of the English landowners: ruling benevolently over their estates and the tenants who inhabited the associated villages, presiding over the courts and local churches, hunting and visiting their neighbors and paying for the weddings and funerals of the poor. To play the role of the peasantry in this semi-feudal system, they imported indentured servants from among the English poor. But unlike English villagers, who were engaged in a variety of subsistence farming endeavors or local forms of production in much the same way that their ancestors had been, the indentured servants of Tidewater were mostly put to work farming tobacco for export.

This may not seem like a huge difference — does it really matter if you’re growing wheat or tobacco, if you’re farming someone else’s land? — but it had profound implications for what happened after the indenture. In theory, the formerly-indentured should have taken on the role of either the English tenant farmer (think Emma’s Robert Martin) or yeoman/freeholder (a small-time landowner but not of the scale or social class to be a “gentleman”). In practice, though the colony was a plantation economy exporting a cash crop: there was very little local manufacturing, since it was so easy for a ship from London or Bristol to sail right up to some great landowner’s dock on the river and unload whatever he might have ordered. Independent small-scale farmers simply couldn’t compete for tobacco export with their larger neighbors, and especially not if they also had to pay rent. But luckily for them, they had something no Englishman had had for centuries: empty land nearby. Or, you know, sort of empty. (Several of the rebellions in early Virginia were fought over the colonial government’s refusal to drive the Indians off the land former servants wanted to settle.) They could just leave.

The obvious solution for the Tidewater elites — the clear way for gentlemen to maintain an aristocratic lifestyle without a peasantry tied to the land — was African slaves. And here’s the important difference between Tidewater and it neighboring nation, the Deep South: Tidewater turned to slavery in the hopes of perpetuating their social structures, while the Deep South was envisioned from the first as a slave society.

The Deep South had been founded in the 1670s by Barbados sugar planters who ran out of room on their tiny island and were now exporting their particularly brutal combination of slave gangs and sugarcane to the coastal lowlands around Charleston Harbor. (Like the Tidewater gentry, the Barbadians had originally experimented with indentured servants from Britain, but they were worked to death so rapidly that the authorities objected.) The planter class quickly became phenomenally wealthy — by the American Revolution, per capita wealth in the Deep South was four times that of Tidewater and six times either New York or Philadelphia, and the money was much more concentrated than anywhere else in the colonies — but unlike the manorial idyll of Tidewater, with its genteel pursuits and colonial capitals all but abandoned when the legislature was out of session, the Deep South planters spent as much time as possible in the city.

Charles Town (later Charleston), South Carolina, modeled on the capital of Barbados, was filled with theaters, taverns, brothels, cockfighting rings, private clubs, and shops stocked with goods imported from London. Life in the city was a constant churn of social engagements, signalling, and status competition: in 1773, a pseudonymous correspondent wrote in the South Carolina Gazette that “if we observe the Behavior of the polite Part of this Country, we shall see, that their whole Lives are one continued Race; in which everyone is endeavouring to distance all behind him, and to overtake or pass by, all before him; everyone is flying from his Inferiors in Pursuit of his Superiors, who fly from him with equal Alacrity…” The planters of the Deep South had no interest in being lords of their estates, which were managed by overseers, or indeed in their land or the people who worked it. Certainly there existed poor whites in the colonies of the Deep South, but they never entered into the conversation: where Tidewater imagined agricultural labor performed by the English “salt of the earth” but had to fall back on slaves, the Deep South always planned on slaves.

This may not seem like an important difference, especially if you’re a slave,6 but it matters a great deal for national character. Culture, after all, lives as much in a people’s values and ideals as in their daily routines: a culture that praises loyalty to clan and family will behave very differently from one that lauds fair dealing with strangers. And the Deep Southern ideal, the nation’s vision of how life ought to be, was more or less Periclean Athens: a tremendous efflorescence of wealth, art, and personal distinction for the great and the good, with no consideration whatsoever for the slaves and metics who made up the bulk of the population. A good life meant leisure and luxury, wealth and freedom, the full exploration of personal capacity for the few and who cares about the many. The Tidewater ideal, on the other hand, was basically the Shire: bucolic, rural, politically dominated by a cousinage of great families who shared a profound sense of noblesse oblige and populated by a virtuous, hardworking yeomanry who knew their place but were worthy of their betters’ respect.

Did that world actually exist? Of course not, neither here or in its English model,7 any more than the Puritans’ commonwealth in Massachusetts Bay was a new Zion inhabited by saints. But a culture’s picture of how life ought to be determines its reaction to changing circumstance, and Tidewater pictured an enlightened rural gentry ruling benevolently over lower orders who nevertheless mattered. In contrast to the aggressively middle class northern nations, the fiercely independent Appalachians, and the elite-centric Deep South, Tidewater imagined itself as an aristocracy. And it was the only one among the American nations.

Tidewater had a disproportionate influence on the early United States, contributing far more than its fair share of early statesmen and generals as well as a healthy dose of the philosophical underpinnings for many of our founding documents. Unfortunately for the lowland Virginia gentlemen, however, they were hemmed in to the west by the hill people of Greater Appalachia: when the other nations began to expand deeper into the continent after 1789, Tidewater was stuck in its starting position. Soon the nation that had been “the South” on the national stage was dwarfed by Greater Appalachia (more than doubled between 1789 and 1840) and especially by the Deep South (ten times larger). When the young United States began to polarize over the issues of slavery, Tidewater — by then a minority in Maryland, Delaware, North Carolina, and even Virginia8 — had to retreat to the political protection of the Deep South and began to lose its cultural distinctiveness. It never really emerged again as its own ideological force.

People like to point out that the political Right in America, split as it is between redneck populists and classically-liberal free marketeers, lacks the European conservatives’ emphasis on order and tradition, place and class, throne and altar and blood and soil and so forth. And, pace various European immigrants over the years and a few weirdos on the Internet, that’s true. But it’s interesting to imagine what our politics might look like today if Tidewater had remained a force on the national stage and if any substantial strain in America could say, with John Randolph of Roanoke, “I am an aristocrat. I love liberty, I hate equality.”

So there’s Tidewater, lost and forgotten except for some guys in Virginia who still put on red jackets to hunt foxes from horseback — and maybe in slightly different voting patterns. What about the nation that won, the one that’s everywhere?

I refer, of course, to Yankeedom.

“But Jane,” you say, “Yankeedom isn’t everywhere! Scroll back up to your own map — it’s in New England, sure, and, uh, northeastern Ohio and, wow, okay, the entire Upper Midwest. But that’s not everywhere.” But ignore the map for a moment: that’s Woodard’s idea, based on settlement patterns and voting behavior. What is Yankeedom, really? What are its fundamental beliefs, its vision of how life ought to be, and where do they show up today?

Of course you know the story of Yankeedom’s founding: radical Calvinists from East Anglia, settled around the Massachusetts Bay in the 1620s and 30s, funny hats? Maybe you made one of those hats for your construction paper turkey in first grade — or, if you’re a little younger, maybe you learned a nice poem about welcoming new immigrants for a glowing future of multiculturalism and prosperity. In fact the emphasis on “the Pilgrims” in American civic mythology — never mind the traditional Thanksgiving menu, heavy on quintessentially New England dishes like pie9 — is itself a product of Yankeedom’s cultural dominance, as is the insistence in that familiar story that they left England for religious freedom. It’s true! They did! But there’s a very important final bit that we somehow leave out of the version we teach to elementary schoolers: religious freedom for themselves.

The earliest Yankees imagined their new society as a Protestant utopia, a new Zion, in which they would work out their collective salvation. Any deviation from the straight-and-narrow could doom everyone, so enforcing moral and religious conformity — through banishing heretics or, if necessary, even executing them — was of paramount importance. Yankeedom was meant to be a “city on a hill,” a model for mankind: if only they could be good enough, pure enough, and holy enough, God would bless them abundantly — and then everyone else, seeing their manifest blessings, would naturally emulate them and become holy themselves! The important thing, then, was not merely to do right but to be seen to do right, as an example to neighbors and foreigners alike. Yankeedom also put a tremendous emphasis on education (literacy was necessary to read the Word of God), encouraged subordinating the interests of the individual to the greater good of the community, and saw government as an extension of the citizenry. Government, then, since it was run by and for the people, was naturally called to propagate God’s will in a corrupt and sinful world by prohibiting or regulating immoral activities.

As Yankeedom moved west, out of the strict control of the Congregationalist ministers who dominated the New England colonies, they began to abandon their specific religious tenets. Sometimes this meant exciting new religious — the Yankee-settled western portions of New York State gave rise to such religious enthusiasms that people began to call it the “Burned-Over District”10 — but just as often it meant becoming a Methodist, Unitarian, or Baptist. Wherever they went, though, the Yankees clung to their belief that you could make earthly society resemble Heaven, or at least that there was no excuse for not trying as hard as you could. Yankees were at the heart of every push for social reform, from abolitionism and the temperance movement to Reconstruction, the minimum wage, women’s suffrage, and an end to child labor. For example, the members of New York City’s Committee of Fifteen, which militated against gambling and prostitution, were mostly Yankees or German-Jewish immigrants; none were culturally New Netherlanders.

By now this should all be sounding familiar. Heavy emphasis on education, embrace of the government regulation or prohibition of immoral behavior as the central bulwark of societal virtue, extremely visible adherence to highly specific rules and norms of behavior as proof of righteousness? Oh, look, it’s woke! It’s the ideology of the professional-managerial class, the meritocratic elite — it’s the same people with the same bumper stickers on the same Mercedes SUVs in the Whole Foods parking lot that you see in every major American city, regardless of which “nation” most of the other residents belong to.

There are two things going on here, I think: first, high-cultural capital Americans are far more mobile than they used to be. Plenty of people spend a few years in DC, then a few years in Austin, or maybe San Francisco or Boulder or Brooklyn, regardless of where they grew up. Second, and perhaps more important, is the role of education. Maintaining or improving your class position depends far more on a “good” college than it used to (witness the to-do when someone claims the distinction of Harvard on a night school degree!). The Yankee emphasis on education means that most of America’s prestigious colleges and universities are in Yankee-settled areas.11 Thus, membership in a higher stratum of society practically depends on four or eight years marinating in Yankeedom. What’s a kid from rural Nebraska to do?

Alas, the final chapters of Woodard’s book, which address the American “culture wars” of the last few decades, descend firmly into polemic. The “Northern alliance,” he writes (Yankeedom, “live-and-let-live” New Netherland, and the Left Coast) support attempts to “better society through government programs, expanded civil rights protections, and environmental safeguards” and “increased spending on education, research, and child care.” The opposing “Dixie bloc” (the Deep South, Greater Appalachia, and a rump Tidewater) is dominated by the Deep South’s desire to “control and maintain a one-party state with a colonial-style economy based on large-scale agriculture and the extraction of primary resources by a compliant, poorly educated, low-wage workforce with as few labor, workplace safety, health care, and environmental regulations as possible.” When the other members of the coalition might object to these manifestly wicked schemes, they are kept in line by “racism and religion.” (I need hardly delve into the afterword to the tenth-anniversary edition and its treatment of the Trump presidency.)

And that’s too bad, because Woodard’s portrait of the American nations actually has some interesting implications for our present cultural Cold War. For one thing, it makes it very clear why a “national divorce” can never happen: for the Yankee-dominated blue states, and the Yankee-acculturated elite everywhere, the idea of letting someone go off on their own and keep being wrong is utterly anathema. For another, it goes a long way to explaining the anti-elitism of the American Right, which tends to be opposed not just to our present Left-leaning elite but to elites generally: it’s the Greater Appalachian strain, suspicious and resentful of anything that smacks of arrogance or condescension.

But the most interesting implications are for American culture (or, fine, the American cultures) in an era of mass immigration. Woodard insists on his Doctrine of First Effective Settlement — the idea that newcomers don’t really change the culture much — but he also goes out of his way to emphasize that the waves of Protestant, northwestern European immigrants who settled in the Midwest — mostly Germans and Scandinavians — specifically picked their regions on the basis of pre-existing cultural affinity. Germans went to Midland areas already heavily influenced by the waves pre-Revolutionary German immigration; Scandinavians, already committed to an ethic of frugality, sobriety, and minding their neighbors’ business civic responsibility, settled in Yankee areas. “The Scandinavians,” the Rev. M. W. Montgomery wrote in 1886, “are the ‘New Englanders’ of the Old World. We can as confidently rely upon them to help American Christians rightly [make]…‘America for Christ’ as we can rely upon the good old stock of Massachusetts.”

The more culturally-distant immigrants who began to arrive in great numbers in the late 19th century — southern and eastern Europeans, Catholics and Orthodox and Jews — were another matter: there were no regions of pre-existing cultural affinity. Luckily (?) for them, the industrial areas they settled generally had substantial Yankee populations who were only too happy to turn them into good Americans — which meant good Yankees — and generally by the extremely Yankee means of public schooling. Horace Mann, the “father of American education,” wrote in 1845 that “[a] foreign people, born and bred and dwarfed under the despotisms of the Old World, cannot be transformed into the full stature of American citizens merely by a voyage across the Atlantic, or by subscribing to the oath of naturalization.” Thus school, to train their children in “self-government, self-control, a voluntary compliance with the laws of reason and duty.” (Thus also the disproportionate emphasis on the experience of Yankeedom — the Pilgrims, the Boston Tea Party, Paul Revere — in our civic mythology: our elementary school picture of What It Means To Be American was invented by Yankee institutions to assimilate immigrants.) Sure, maybe the Yankee strain persisted because they were there first — but the Yankees also worked very hard to make sure it would.

Our present wave of immigration, which more or less matches the peak of the late 19th/early 20th century “Great Wave,” differs from it in a couple of important ways. First, the “melting pot” model — in which immigrants are transmuted into Yankee-style Anglo-Protestants — is no longer in style; instead we’re supposed to imagine a “tossed salad” (or, if that’s too embarrassing, a “cultural mosaic”) where we all integrate joyously while maintaining our separate identities. Assimilation is out, multiculturalism is in — and at the same time, the differences between those separate identities are much larger than they were a hundred years ago. Just as a Swedish Lutheran is much closer to a New England Congregationalist than is a Slovak Catholic, the Slovak Catholic is still closer than a Somali Muslim or a Hausa animist.

Woodard isn’t troubled, arguing that since we have so many different regional cultures, so many different ideas of what it means to be an American, mass immigration can’t possible undermine or destroy “Americanness.” As concerns Mexican immigration just over the border, he may be right: norteños on either side of the Rio Grande probably have more in common with each other culturally than either groups does with the people in their capital. But many of the new immigrants aren’t Mexican and aren’t settling in El Norte at all, and Woodard gives countless examples of sufficiently large numbers of newcomers shifting local culture. The most dramatic one is that of Georgia, founded as a utopian colony where the destitute dregs of England’s cities might reform themselves through honest work into yeoman farmers but quickly transformed into an outpost of the Deep South. There’s also the conquest of Texas, California, and Louisiana by the various Anglo-derived cultures, leaving El Norte and New France on the periphery, or the genesis of the Left Coast in the arrival of Appalachian farmers in the countryside around the Yankee-settled cities — or Chicago, founded by Yankees but, Woodard writes, “soon overwhelmed by new arrivals from Europe, the Midlands, Appalachia, and beyond.” Sure, Chicago is more Yankee than Iowa or southern Illinois — but it’s not Boston or Minneapolis, either.

Of course, right now none of the American nations are anywhere near the tipping point for total cultural obliteration. The actual risk is not to the perpetuation of any of our regional cultures but to the impersonal prosocial norms and institutions they all depend on, which are far more fragile.

Each wave of immigrants to America has been less WEIRD than the last: first Anglo Protestants (among the WEIRDest people in the world, though the Borderlanders who settled in the Appalachians somewhat less so), then other Protestant groups from Northwestern Europe (also very WEIRD), then largely Catholic Europeans from other regions (still pretty WEIRD on a global scale). Some of those third wave immigrant groups’ descendants continue to be noticeably less WEIRD, even after several generations in the US and despite the Yankees’ concerted efforts to indoctrinate their ancestors into WEIRD values. The present wave of immigration is largely from places that are not WEIRD at all, at the same time as the indoctrination efforts have vanished entirely. Partly it’s because assimilation is no longer de rigueur, but it’s also partly because the intelligentsia that used to do the indoctrinating has become convinced that WEIRD impersonal institutions (law, government, markets, police, etc.) are bad, actually. They’re not out there personally breaking laws or corruptly favoring the in-group, but they won’t condemn anyone else for doing so.

It takes a lot of newcomers with a different culture to really replace what was already there. It takes many fewer defectors from the existing norms to make your current approach — honesty boxes, obeying parking laws, paying subway fares, turning in a lost wallet with its contents intact, leaving a bowl of Halloween candy on your front porch — impossible. Now, you may say that none of those are big deals: after all, who does it really hurt if no one leaves candy on their porch? For this you become an immigration skeptic? But the same mindset that produces “take one” produces a people who don’t lie on the witness stand even to protect a friend, or who would be insulted to be offered a bribe for special treatment. The same mindset, the expectation that you will cooperate with and behave fairly towards anonymous strangers and abstract institutions like the police or government, is what our entire society is built on.

If we no longer trust our neighbors’ behavior, it won’t mean the immediate end of our cultures: a people’s picture of how life ought to be doesn’t change overnight. But neither does it persist indefinitely if it cannot be actively pursued. If we can learn anything from the example of Tidewater’s decline and fall, it’s that the greater the difference between your ideals and your reality, the less hold your ideals come to have over you. In the 1760s Tidewater statesmen could abhor slavery and look forward to its gradual disappearance (while of course continuing to own slaves); by the 1860s, another century with no doughty yeomanry meant that the scions of its oldest families were embracing the Deep Southern idea that slavery was the natural condition of most of mankind and really ought to be extended to poor whites as well. Would Yankee thrift survive generations of high inflation? Did Greater Appalachian clannishness survive the move north? How much of change does it take before something important is lost? But hey, maybe we’ll get to find out.

Including plenty of Jane Psmith-bait like discussion of who was into boiling (the East Anglians who adopted coal early and moved to New England) vs. roasting (the rich of southern England who could afford wood and moved to the Chesapeake Bay), discussions of regional vernacular architecture, the distinctive sexual crimes each group obsessed about (bestiality in New England, illegitimacy in Chesapeake) and so on — I love this book.

Incidentally, if you’ve only read Scott Alexander’s review of Albion’s Seed, do yourself a favor and read the actual book. Yes, Scott gives a perfectly cromulent summary of the main points, but it’s a such gloriously rich book, full of so many stories and details and painting such a picture of each of the peoples and places it treats, that settling for the summary is like reading the Wikipedia article about The Godfather instead of just watching the darn movie.

Yes, there is a book for this, and it’s apparently Russell Shorto’s The Island at the Center of the World, which I have not read and don’t particularly plan to.

Off the top of my head:

The Deep South tried to get the United States to conquer and colonize Cuba and much of the Caribbean coast of Central America as future slave states;

There were a wide variety of other secession movements in the run-up to the Civil War, including a suggestion that New York City should become an independent city-state that was taken seriously enough for the Herald to publish details of the governing structure of the Hanseatic League;

In 1784 the residents of what is now eastern Tennessee formed the sovereign State of Franklin, which banned lawyers, doctors, and clergymen from running for office and accepted apple brandy, animal skins, and tobacco as legal tender. They were two votes away from being accepted as a state by the Continental Congress.

I was reading about James Garfield, a native Ohioan, and was sufficiently struck by his family’s emphasis on education and vehement abolitionism to look it up; sure enough, his father was from (Yankee) Upstate New York, his mother from New Hampshire, and he was raised in the Yankee-settled Western Reserve.

Though it actually mattered a great deal to slaves, who were imported to the Deep South in great waves only to be worked to death; the enslaved population of Tidewater, by contrast, increased steadily over the entire antebellum period.

Though I will point out that Akenfield suggests the total immiseration of the tenant farmers in the early 20th century has something to do with the land being owned by rich farmers and implies that the local gentry are more generous employers.

West Virginia’s eventual secession back to the Union would put Tidewater back in the majority there.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, in Oldtown Folks, as quoted in Albion’s Seed:

The pie is an English institution, which, planted in American soil, forthwith ran rampant and burst forth into an untold variety of genera and species. Not merely the old mince pie, but a thousand strictly American seedlings from that main stock, evinced the power of American housewives to adapt old isntitutions to new uses. Pumpkin pies, cranberry pies, huckleberry pies, green-currant pies, peach, pear, and plum plies, custard pies, apple pies, Marlborough-pudding pies,—pies with top crusts, and pies without,—pies adorned with all sorts of fanciful flutings and architectural strips laid across and around, and otherwise varied, attested the boundless fertility of the feminine mind, when let loose in a given direction.

For more on the history of distinctly American pies, including why they’re so different from the English pies you may have seen on The Great British Bake-Off, I highly recommend BraveTart: Iconic American Desserts, which is somehow both the best history of American sweets I’ve ever read and the best cookbook for them.

Famous alumni of the Burned-Over District include the Seventh-Day Adventists, John Humphrey Noyes’s Oneida Community, and the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints. (Yes, Mormons are Yankees. Obviously.) But my favorite wacky Yankee religious enthusiasm — actually in Massachusetts, where they weren’t branding people with H for heretic any more — was John Murray Spear’s “New Motive Power,” an attempt to build an electric perpetual motion machine Jesus.

The exceptions are generally the flagship school of a large non-Yankee region or in California, the culture of which I’ve entirely elided for reasons of brevity. Sorry. The tl;dr is that Woodard argues the “Left Coast” is a hybrid of Yankees settling the cities and Greater Appalachia in the countryside, which leads to culture fairly similar to that of Yankeedom.

I find it kind of interesting that you went from

"Tidewater stopped serving a practical purpose and died" and "Yankees are the origin of woke, which we hate and no longer serves a practical purpose" to "Oh no, what happens if immigrants dilute or change our dominant Yankee culture?"

To the extent that the law of first settlement is real and you're concerned about woke, your main concern about immigration should be *ruining the immigrants.* To the extent culture is actually malleable, you should see modulating immigrants as a potential to undermine the vices of Yankeedom and instill new balancing virtues. It's strange to both hate what the ruling stock of America has become and *also* be a nativist fearful of cultural change from those foreigners over there.

Notably, when I think about the unusual traits of Americanism most worth preserving and emulating, it's like "brusque honesty and fair play and yeomanry not taking shit or charity from anyone." This seems like not an entirely Yankee set of virtues, and notably most of even the cardinal Yankee virtues are now gone from their cultural descendants (fecundity, concern for education as such).

I feel like the initial map isn't quite right (though I skipped down here to comment, so forgive me if this is addressed within the essay/review) — at least, *my perception is* that here in West Texas (grew up in & then returned to the area just to the east of that right angle with NM there, + also some way to the north-east; Lubbock and Midessa, that is) the culture has merged to great extent with "El Norte", and this merged culture is a) certainly now "its own thing", and b) drops off sharply once you get too much farther toward Ohio or Tennessee.

That is, by the metric mentioned at the beginning — the feeling of familiarity and comfort (which was an excellent illustration of the idea behind the book, btw! it was immediately evocative and comprehensible to me; I just couldn't quite feel at home anywhere else in the U.S.) — (West) Virginia isn't in the same "nation" as WTX at all, to my mind. Not enough Hispanics, not enough breakfast tamales...

It's hard for me to be sure, given my limited time spent living in other places (moved about once a year all over the country till coming back home; the Northeast is what I hated the most, heh), but my impression is that there IS validity to the "Greater Appalachia" outlined in the map: feel quite comfortable with people from Oklahoma and Arkansas.

The second-place spot goes to states like Wyoming or Montana; not sure how much historical continuity they share with us down here, but they feel much more familiar than anywhere else I've been (aside from Greater Appalachia, of course, esp. the more southwestern parts).

Interestingly, though the very eastern bits of NM are nearly indistinguishable from the local culture IME (e.g. Hobbs), the most of the state is more unlike us than, say, Kentucky. Same with CO, I think, on the whole. The book got that right, for my money!

Just my anecdata... so to speak! Great Substack, the only one that's really grabbed me since following Scott "Alexanderkind" here.