REVIEW: Science in Traditional China, by Joseph Needham

Science in Traditional China, Joseph Needham (Harvard University Press, 1981).

There’s an old trope that the Chinese invented gunpowder and had it for six hundred years, but couldn’t see its military applications and only used it for fireworks. I still see this claim made all over the place, which surprises me because it’s more than just wrong, it’s implausible to anybody with any understanding of human nature.

Long before the discovery of gunpowder, the ancient Chinese were adept at the production of toxic smoke for insecticidal, fumigation, and military purposes. Siege engines containing vast pumps and furnaces for smoking out defenders are well attested as early as the 4th century. These preparations often contained lime or arsenic to make them extra nasty, and there’s a good chance that frequent use of the latter substance was what enabled early recognition of the properties of saltpetre, since arsenic can heighten the incendiary effects of potassium nitrate.

By the 9th century, there are Taoist alchemical manuals warning not to combine charcoal, saltpetre, and sulphur, especially in the presence of arsenic. Nevertheless the temptation to burn the stuff was high — saltpetre is effective as a flux in smelting, and can liberate nitric acid, which was of extreme importance to sages pursuing the secret of longevity by dissolving diamonds, religious charms, and body parts into potions. Yes, the quest for the elixir of life brought about the powder that deals death.

And so the Chinese invented gunpowder, and then things immediately began moving very fast. In the early 10th century, we see it used in a primitive flame-thrower. By the year 1000, it’s incorporated into small grenades and into giant barrel bombs lobbed by trebuchets. By the middle of the 13th century, as the Song Dynasty was buckling under the Mongol onslaught, Chinese engineers had figured out that raising the nitrate content of a gunpowder mixture resulted in a much greater explosive effect. Shortly thereafter you begin seeing accounts of truly destructive explosions that bring down city walls or flatten buildings. All of this still at least a hundred years before the first mention of gunpowder in Europe.

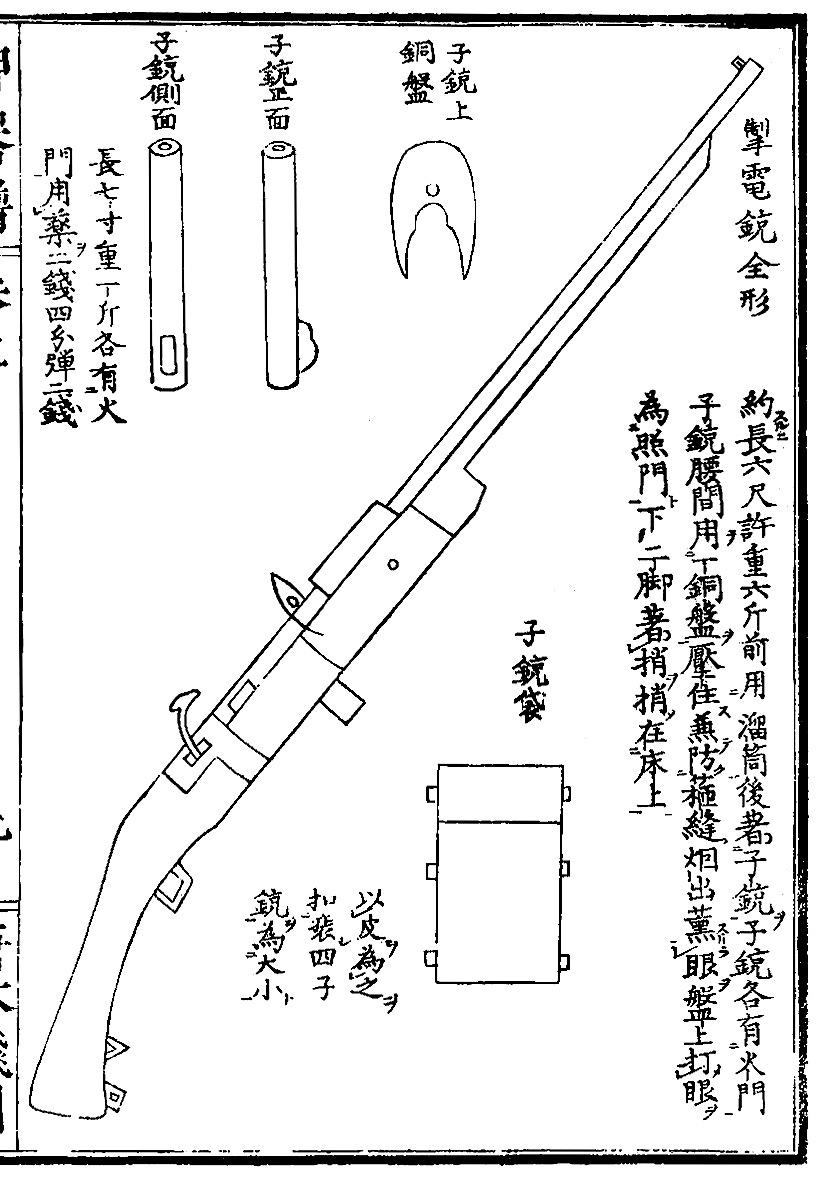

Meanwhile, they had also been developing guns. Way back in the 950s (when the gunpowder formula was much weaker, and produced deflagarative sparks and flames rather than true explosions), people had already thought to mount containers of gunpowder onto the ends of spears and shove them in peoples’ faces. This invention was called the “fire lance”, and it was quickly refined and improved into a single-use, hand-held flamethrower that stuck around until the early 20th century.1 But some other inventive Chinese took the fire lances and made them much bigger, stuck them on tripods, and eventually started filling their mouths with bits of iron, broken pottery, glass, and other shrapnel. This happened right around when the formula for gunpowder was getting less deflagarative and more explosive, and pretty soon somebody put the two together and the cannon was born.

All told it’s about three and a half centuries from the first sage singing his eyebrows, to guns and cannons dominating the battlefield.2 Along the way what we see is not a gaggle of childlike orientals marveling over fireworks and unable to conceive of military applications. We also don’t see an omnipotent despotism resisting technological change, or a hidebound bureaucracy maintaining an engineered stagnation. No, what we see is pretty much the opposite of these Western stereotypes of ancient Chinese society. We see a thriving ecosystem of opportunistic inventors and tacticians, striving to outcompete each other and producing a steady pace of technological change far beyond what Medieval Europe could accomplish.

Yet despite all of that, when in 1841 the iron-sided HMS Nemesis sailed into the First Opium War, the Chinese were utterly outclassed. For most of human history, the civilization cradled by the Yellow and the Yangtze was the most advanced on earth, but then in a period of just a century or two it was totally eclipsed by the upstart Europeans. This is the central paradox of the history of Chinese science and technology. So… why did it happen?

I first encountered Joseph Needham’s name when reading a completely different book about Chinese history. This book mentioned in passing a naval battle that occurred on a lake, right on the cusp of a period of major anarchy, in which one of the factions was a demented cult that built ships in the form of giant human-powered hamster wheels. I obviously wasn’t about to let that endnote slip by me, and when I went to check the bibliography it pointed me towards Needham’s by all accounts magisterial and definitive seven volume series Science and Civilization in China, which Amazon will ship to your door for a mere $8,000 or so. Alas, that’s a little outside the Psmith household’s budget for books, so I had to make do instead with the slim collection of lectures that is the subject of this review.

The book consists of an introduction followed by the text of four lectures that Needham gave, towards the end of his career, at the Chinese University in Hong Kong. Needham is clearly a gunpowder fan, and devotes an entire lecture to the history of its invention and of its application to military and non-military uses. He then moves on to all the non-gunpowder aspects of Chinese alchemy, and its connections to Islamic and European alchemy.

My favorite thing in this chapter is an etymological nugget that I suspect is too good to be true, but which I desperately want to believe. The word “alchemy” comes from the Arabic al-kīmiyāʾ (الكيمياء), which in turn comes from the Greek khēmeia (χημεία), but that’s where our knowledge of this word stops. χημεία has no known Indo-European origin, and no obvious cognates that would suggest a borrowing. There are some hand-wavy theories that it might derive from khēmet, the word for Egypt in ancient Egyptian, but it’s a stretch to put it mildly. Needham proposes the Chinese 金 meaning “gold” as the ultimate source. In modern Mandarin, this word is pronounced like jin, but the Classical Chinese pronunciation is better preserved by the Southern dialects, which variously render it as gum, gim, or, in Hakka and Southern Min, as kim. The list of English words with Chinese origins is short,3 and it would be nice to add this one.

But the Chinese alchemists by and large weren’t after gold, their goal was eternal life instead. In fact aurifaction originated as an instrumental “warm-up” exercise for the main event. Everybody knew that the reason gold was the most perfect metal was because it was a harmonious and balanced combination of the elements. So if the same harmoniousness and lack of internal contradiction could be achieved within a living organism, then the consequences would obviously be physical immortality and superhuman abilities. Elemental harmony, biological harmony, social harmony — in the light of Chinese metaphysics these goals were all reflections and intimations of one another. And the first two at least could be brought about by the same methods: the application of various potions and elixirs designed to increase or reduce the influence of a particular element. The same principle forms the cornerstone of Chinese medicine today.4

All of this is very nice, but does it get us closer to an answer to the question I posed? Why, despite China’s prodigious lead in science, technology, population, and economic activity, did the scientific revolution and then the industrial revolution happen in Europe? Why did they fall so far behind after being so far ahead?

There are all kinds of answers given to this question, from ones based around the concept of “agricultural involution” (which I briefly surveyed in my review of Energy and Civilization), to ones that blame the complexity of the Chinese system of writing and other more outlandish theories. But would you know it, this question is commonly referred to within Sinology as the “Needham puzzle” or the “Needham question”, so what does the man himself think? Needham got the credit for posing the question, not for answering it, but in the final chapter of this book, “Attitudes Towards Time and Change”, he drops some fascinating hints.

A belief common to the great civilizations of the Axial Age was that time itself was somehow unreal. Greek philosophers from the pre-Socratics to the Neo-Platonists all expressed it in very different ways, but all agreed that in some sense the world of mutability and change was an illusion, and that outside of it stood an eternal, absolute reality sufficient in itself, unchanging in its perfection, αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων. The Buddhist civilizations include this under the doctrine of maya (illusion), and traditional Hinduism also exhibits time as a dreamlike and incidental quality of the world.

If time is somehow unreal and nothing can ever change, then it’s easy to see the attraction of a cyclic conception of history. And indeed, in the ancient world these cyclic theories predominate. The Babylonians had their Great Year, and Greek thinkers as diverse as Hesiod, Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle all speculated about the eternal repetition and recurrence of the ages of the world. In the Mahabharata the great yugas and kalpas, the Days of Brahma, follow one another in an inevitable fourfold cycle of world ages, the profusion of Hindu and Buddhist sects have promulgated a thousand interpretations and variations on this basic pattern. On the other side of the world, the Mayans had their own Great Year, and countless other peoples besides. This cosmology almost feels like a human universal (at least for civilizations at a particular stage of development), and why wouldn’t it be? We open our eyes and all we see are cycles within cycles — the cycle of the day, the cycle of the moon, the cycle of the seasons, the cycle of the generations. As sure as day follows night, why wouldn’t we expect that the universe too, a grand mechanism made by the gods, must eventually return to its starting point.

Various philosophers of science have asserted that this view of history makes scientific progress impossible, because of its fatalism and pessimism. If everything that happens has happened before and will happen again, then why bother trying to change anything? It’ll just get undone in the Kali Yuga anyway. But Needham points out another connection: if time is cyclic, or worse yet somehow unreal, then it makes no sense to stretch it out into an independent coordinate. In this way, the entire metaphysics of cyclical time resists the mathematization of physics. One can imagine the analytic geometry of Descartes being discovered in ancient Alexandria or Tikal or Harappa, but would it have been possible for one of the coordinate axes to represent time? A Descartes was possible, but a Newton or a Bernoulli was inconceivable.

All of this changes with the advent of Christianity, for which the most important fact about the world, the Incarnation, takes place at a particular moment in history, once and for all, κατὰ πάντα καὶ διὰ πάντα. The cosmos is fixed around this central point, and cannot curl back upon itself. Kairos transfigures chronos, and in so doing makes it real, gives it force and meaning. History is not a cycle, but a story of creation, separation, incarnation, and redemption, speeding towards its culmination as assuredly as a stone tracing a parabolic arc through the air. Or as Needham puts it:

[In the Indo-Hellenic world] space predominates over time, for time is cyclical and eternal, so that the temporal world is much less real than the world of timeless forms, and indeed has no ultimate value… The world eras go down to destruction one after the other, and the most appropriate religion is therefore either polytheism, the deification of particular spaces, or pantheism, the deification of all space… For the Judaeo-Christian, on the other hand, time predominates over space, for its movement is directed and meaningful… True being is immanent in becoming, and salvation is for the community in and through history. The world era is fixed upon a central point which gives meaning to the entire process, overcoming any self-destructive trend and creating something new which cannot be frustrated by cycles of time.

Some historians of science have argued that without this linear conception of time introduced by Christianity, we lack the conceptual vocabulary for various things ranging from analytic methods in physics to the idea of causality itself. So is that the answer? Is the solution to the Needham Puzzle that China progressed as far as it could until, weighed down by the fatalism of cyclic history and the impoverished mathematical vocabulary of timeless metaphysics, it ground to a halt?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. This theory sounds great, but it’s totally wrong.

There’s a bad habit among Western historians and philosophers of engaging in a shallow sort of orientalism that aggregates all of the exotic East into a single entity.5 But when it comes to attitudes towards time, change, and history; the traditional Chinese attitude is much closer to that of Christendom than it is to the Hindu or Buddhist view. Needham does a good job summarizing the basic Chinese outlook, but includes a lot of details I didn’t know, including that the view of civilizations as ascending through distinct historical stages (e.g. the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, etc.) is of Chinese origin! Needham also discusses the veneration, sometimes deification, of great inventors that saturates Chinese folk religion. All in all, the picture is one of China as a progress-obsessed society almost from its earliest moments, and as a society that was steadily progressing right up until it was suddenly and dramatically eclipsed by European science.

So we’re back to the puzzle. Why? Needham can’t help us, but I have a crazy guess.

Those of you who have studied physics know that the laws of motion are usually introduced through the mechanics and dynamics of point particles, or of simple objects acting under the influence of discrete and coherent forces. The reason for this is straightforward: even a tiny bit more complexity, and the system’s behavior quickly dissolves into a morass that’s analytically intractable and computationally infeasible. The fact that the mutual gravitational influences of just three celestial objects results in chaotic dynamics has entered into popular culture as the “three-body problem”. But even a simple double-pendulum is impossible to predict, even with all kinds of simplifying assumptions (massless rods, no friction, no air resistance, etc., etc.).

It’s not just physics. The central technique of modern science is that of boiling something down to its absolute simplest form, understanding the simplest non-trivial case as thoroughly as possible, and only then building back up to more familiar situations. In physics we start with contrived gedankenexperimenten: “what if two particles collided in a vacuum”, and build experimental apparatuses designed to mimic these ultra-simple cases. In economics we imagine markets with a single buyer and a single seller, both perfectly rational. In political philosophy we imagine human beings in a state of nature, or societies established by a primitive contract. In biology we try to understand the functions of organisms, organs, or other systems by recursively taking them apart and trying to figure out each part in isolation. In every case, what we’re engaging in is “analysis”, ἀνά-λυσις, literally a “thorough unravelling”, understanding the whole by first understanding its parts.

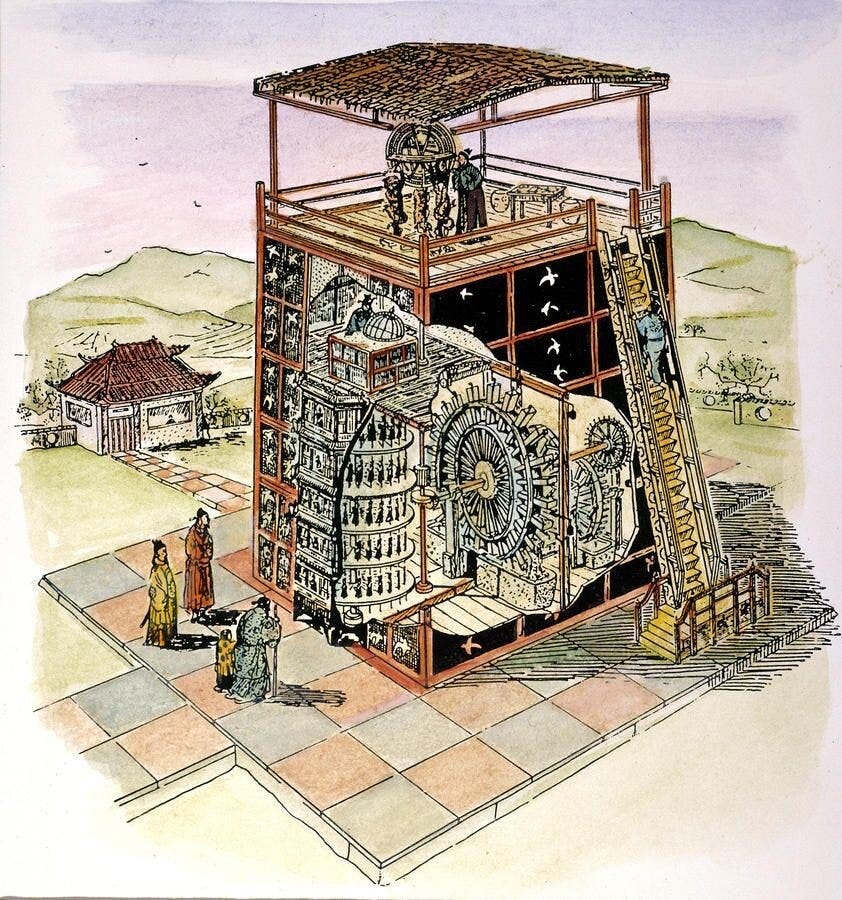

This approach is totally alien to the traditional Chinese understanding of reality, which held instead that no part of the world could be understood except in its relation to the rest of the universe. You can see this in the domains of science where they did maintain a lead. Is it really a coincidence that the Medieval Chinese got frighteningly far with the mathematics of wave mechanics? Or quickly deduced the causes of the tides? Or made great strides with magnetism? In each of these cases, the physical phenomenon in question was compatible with an “organicist conception in which every phenomenon was connected with every other according to a hierarchical order”. Indeed, in all of these cases real understanding was aided by the assumption that a universal harmony underlay all things and connected all things. The tides really are in harmony with the moon, and the lodestone with the earth.

This science, founded on holism rather than on analysis, made great strides in some fields but fell behind in others. It readily imbibed action at a distance, but it could not and would not tolerate the theory of atoms. In this way it serves as a strange mirror of Medieval European science, which also loved the theory of correspondences, also loved alchemy and disdained analysis. The difference is that the glorious intellectual synthesis of Neo-Confucianism was never seriously challenged, it survived the Mongol conquest, it survived the desolation of the civil wars that preceded the Ming founding, it survived everything until communism. In contrast, the eerily-similar Thomistic metaphysics of the High Middle Ages was broken apart by the Reformation, and sufficiently discredited that analytical methods could take their first tentative steps.

This is, to be clear, my own crazy theory, because Needham never really gave a solution to his own puzzle. I came up with it only as a sort of thought-experiment, because I wanted to see if I could find a solution to Needham’s puzzle that disdained material explanations in favor of intellectual tendencies, because I find such theories curiously underrated in our culture. I only half-believe this theory,6 but I find it interesting because twentieth-century Western science has in some ways come back around to the holistic view of things: from Lagrangian methods in theoretical physics, to category theory in mathematics, to systems biology and ecology. It wouldn’t be the first time that a way of viewing the world useful to one age became an impediment to reaching the next one. The question is: what are we missing today?

Needham says he heard of one used by pirates in the South China Sea in the 1920s to set rigging alight on the ships that they boarded.

I’ve left out a ton of weird gunpowder-based weaponry and evolutionary dead ends that happened along the way, but Needham’s book does a great job of covering them.

My favorite of these, since it seems so unlikely, is “ketchup” deriving from 茄汁 (“tomato sauce” in Cantonese), perhaps via the Malay kicap.

Needham’s third lecture is about the most recognizable and well-traveled example of Chinese medicine — acupuncture — and contains the intriguing assertion that naloxone administration totally cancels acupuncture’s efficacy for pain relief. This suggests that acupuncture’s mechanism of action may have to do with stimulating the body’s production of naturally-occuring opioids. There’s some evidence the placebo effect could be related (fascinatingly, naloxone also appears to eliminate the placebo effect).

I am infuriated by restaurants that advertise “Asian food”. There’s more culinary diversity inside some regions of China than there is in most of Europe.

The thing about material conditions is they usually are dispositive!

I'm sure you're aware of the book "Escape from Rome" by Walter Scheidel. Scheidel argues that the advantage Europe had was that its geography led to political fragmentation into smaller states in the aftermath of the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire; whereas China consistently reunified after periods of political fragmentation due to its geography and homogeneity. It's not as simple as "big state squelches innovation," which is--no surprise--popular with libertarians*. Rather, that political fragmentation unleashed interstate competition on a greater scale than in China, which was spared those competitive energies due to its size and centralization, which led to more innovation in Europe. In Europe, for example, if one state innovated militarily, other states had to keep up if not improve on those techniques. Small states like the Dutch Republic had to be innovative (e.g. finance & banking) to compete with more powerful states like Spain. If one country didn't want to send out sailing ships to explore, another one would, and so on. I have not yet read the book, so I can't speak to how good its argument is, but it's one that has been made many times even before Scheidel.

As for the conceptual difference, are you familiar with "The Master and His Emissary" by Dr. Iain McGilchrist? What you're describing as Chinese thought--the idea that nothing can be understood except in the context of the whole--is associated with the way the right hemisphere of the brain (which controls the left side of the body) sees the world. The idea of breaking the world down into isolated component parts and using instrumental rationality is associated with the Left hemisphere of the brain (which controls the right side of the body). McGilchrist argues that both ways of perception are necessary and that we need both, but we run into trouble when one hemisphere becomes dominant to the exclusion of the other. He argues that one of the characteristics of the left hemisphere is an inability to see its own limitations and it often suppresses the activities of the right hemisphere (the 'Master' and the 'emissary' in his depiction.) Furthermore, cultures and historical periods can be understood in terms of which way of seeing the world predominates. It's a magisterial work of 1,000-plus pages, so any summary is, of course, inadequate. There's a popular RSA animation which provides a summary: https://youtu.be/dFs9WO2B8uI

* Of course, historians have shown that Great Britain, where the Industrial Revolution began, had a strong centralized state which could do things like protect property rights, issue patents, hold contests to develop technologies for its navy, and so on; and that--contra libertarianism--strong states foster innovation whereas weak states do not.

Perhaps the paradox of China's eclipse can be explained through more humdrum political events, particularly the divided nature of the European population, which would militate against any force that might slow technological growth. Hard to see how the French could have burned their treasure fleets in the same way that the Chinese did. The fact that so many European countries were so constantly at war with one another, particularly the Thirty years war, naturally drove innovation, particularly military innovation. Paradoxically, one could argue that the generally unified state of China was advantageous until it ceased to be so due to its monopoly on technological growth and its ability to forestall it whenever necessary.

Additionally, there is the issue of Chinese characters and how much more challenging it is to create a printing press to spread literacy and ideas in this sort of environment.