JOINT REVIEW: Origen's Revenge, by Brian Patrick Mitchell

Origen’s Revenge: The Greek and Hebrew Roots of Christian Thinking on Male and Female, Brian Patrick Mitchell (Pickwick, 2021).

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

John: You know dear, we’ve been writing this book review Substack for eight months now, ever since that crazy New Year’s resolution of ours, but we still haven’t done “the gender one.” And I feel like we have a real competitive advantage at this, since both sides of the unbridgeable epistemic chasm between the sexes are represented here. So let’s settle some of the eternal questions: Can men and women be friends? Who got the worse deal out of the curse in the Garden of Eden? And what’s up with your abysmal grip strength anyway?

I was perplexed by these and other questions, but then I picked up this book on the theology of gender, and it all got a lot clearer. The author is Deacon Brian Patrick Mitchell, an Eastern Orthodox clergyman and retired military officer. In a previous life, Mitchell testified before the Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces and then followed that up with a book called Women in the Military: Flirting with Disaster, so he’s been interested in the differences between men and women for a while.

People have been observing for centuries that Christianity can be a little bit schizophrenic on the subject of gender relations. From the earliest days of the Apostolic era, there are two strains in evidence within Christianity: one which shores up the gender divisions common to most agricultural societies, and another which radically transcends them. Oftentimes both strains are visible within a single person! Thus you have the Apostle Paul on the one hand saying in his letter to the Ephesians:

Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church: and he is the saviour of the body. Therefore as the church is subject unto Christ, so let the wives be to their own husbands in every thing. (Ephesians 5:22-24)

But then in Galatians:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

For as long as Christianity has existed, there have been people emphasizing one of these tendencies as the “true” Christian message on gender while attempting to minimize the other. Sometimes these arguments are interesting and sometimes they bring out something important (I’m a fan of Sarah Ruden's Paul Among the People on the one side, and of Toby Sumpter’s fiery homilies on the other), but I think in both cases they’re falling into the error of trying to simplify something that is actually complicated. There’s a certain kind of person who can’t handle inconsistency, and that kind of person is going to have trouble with Christianity, because to a finite being the products of an infinite mind will sometimes appear inconsistent. Does Christianity want women to be subject to men, or does it want men and women to transcend their natures? The answer is very clearly both.

Mitchell’s book is compelling because it doesn’t try to minimize or hide one of these tendencies, but acknowledges up front that they’re both there and both have to be struggled with. It then advances the novel (as far as I know) argument that these two tendencies with regard to gender relations actually reflect the two major ethnic and cultural influences on the early Church: Hebrew and Greek.

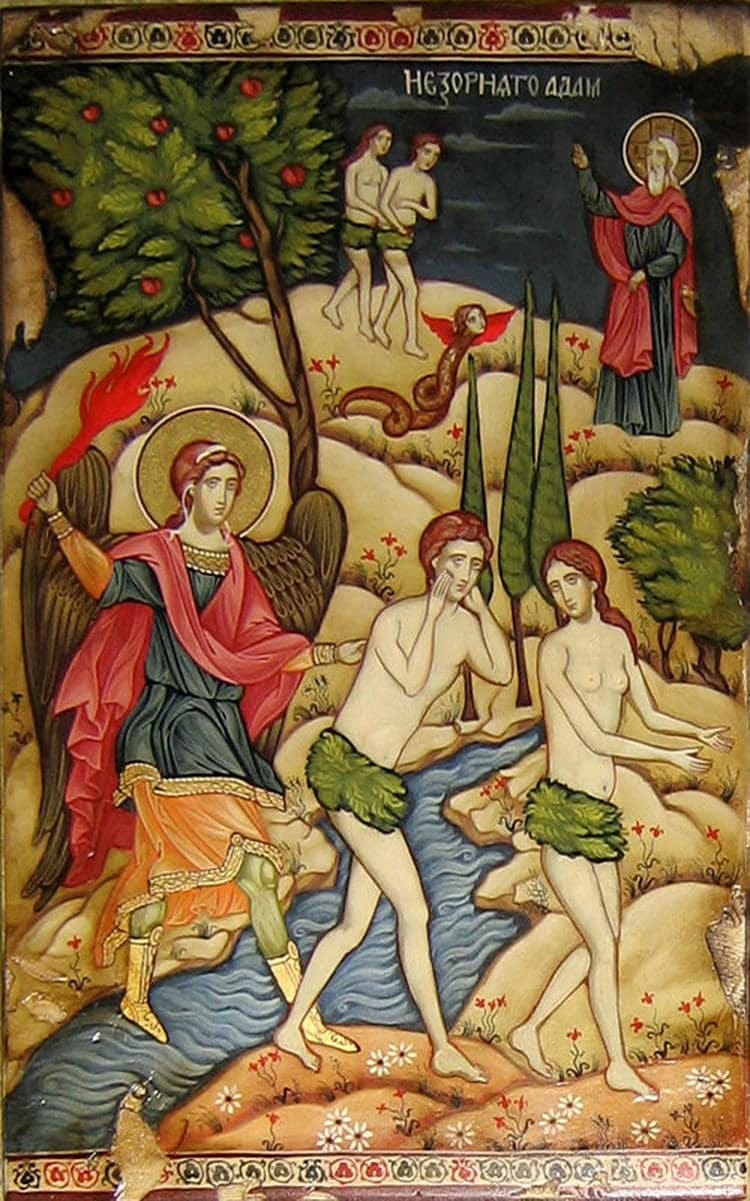

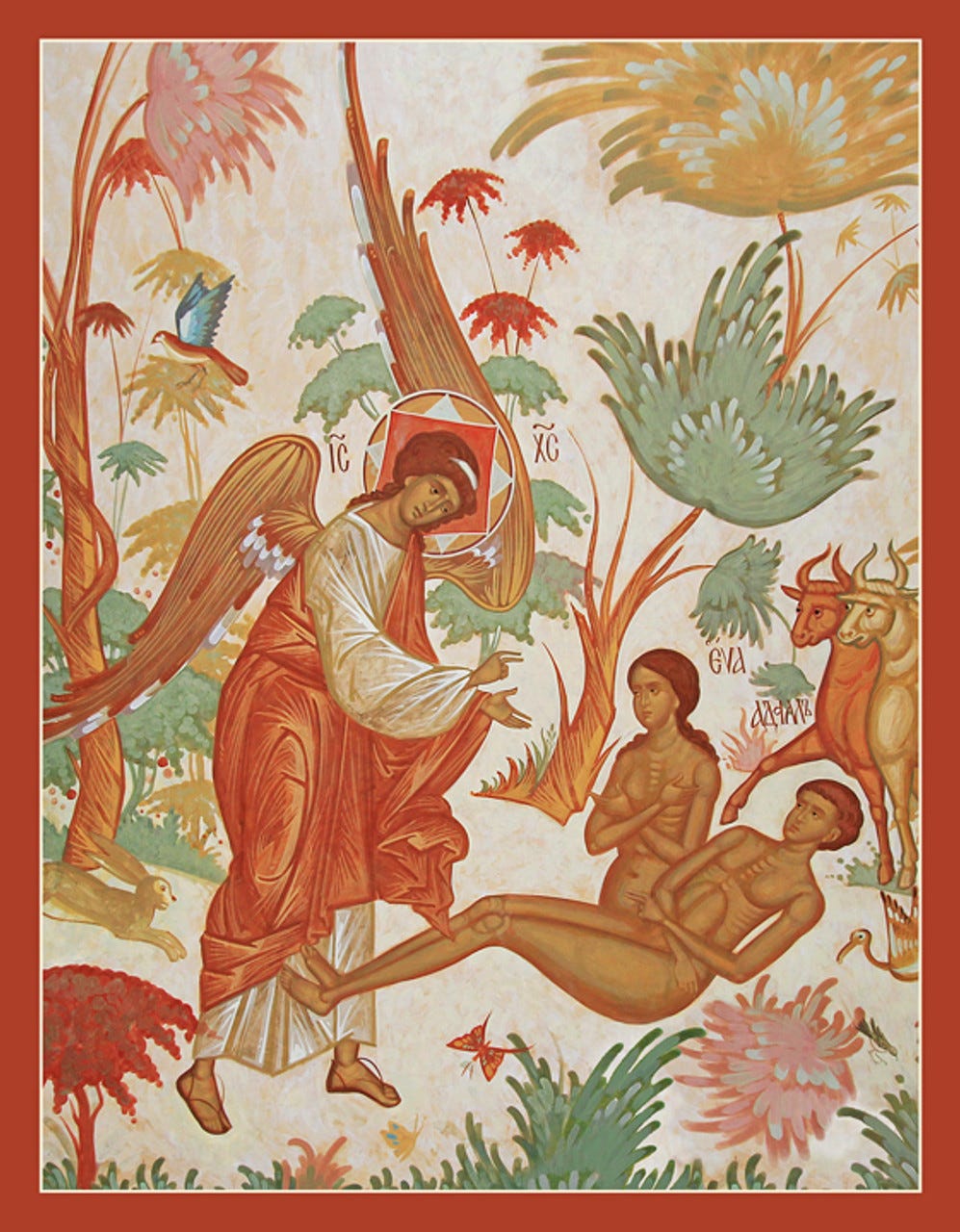

The ancient Hebrew attitudes towards male and female are apparent from the beginning of the Bible: God creates Eve from out of Adam’s rib, and she is called Woman because she was taken out from Man. Thus the woman is subordinated to the man, yet fundamentally made of the same stuff as him. God calls the division of humanity into men and women good, He blesses families and helps barren women conceive, He commands His people to be fruitful and to multiply, and He promises Abraham that his seed shall be numbered as the stars of heaven. The entire Old Testament is a story of families, sometimes dysfunctional families, but families nonetheless, as opposed to lone men roaming the earth as in the Iliad or Bronze Age Mindset. Male headship is assumed, but it’s also assumed that men are fundamentally incomplete without something that only women can give them: a home, a future, and the thing that makes both, children.

So in Mitchell’s telling, the Hebrew legacy is responsible for the more “trad” side of early Christianity. What about the Greeks? Well we already discussed in our joint review of Fustel de Coulanges’ The Ancient City how ancient Greek society was basically the world of gangster rap: honor, boasting, violence, women as trophies, women as a way of keeping score, women torn wailing from the arms of their parents or husbands and forced into marriage or concubinage or outright slavery. You will be shocked to learn that this culture did not hold a high opinion of women, procreation, or the marital union. Greek philosophy is a massively complicated and diverse beast, but there’s a strong tendency within it to associate women with physicality, nature, and brute matter, and to disdain all of these things in favor of rationality, spirit, and the intellect (all coded as male).

Our readers are probably thinking, “Hang on a minute, I thought the Hebrews were the patriarchal ones, do you mean to say that the hyper-masculine and hyper-misogynistic culture was the one that decided maleness and femaleness didn't matter?” Well yes I do, and it's pretty easy to see why if one hasn't been totally brainwashed by modernity, but maybe it’ll be more convincing if a woman explains it to them.

Jane: Well, I think you gave a pretty accurate description of actually-existing ancient Greek culture, but we have to remember that the Church Fathers weren’t classicists poring through the corpus trying to accurately characterize the past. Rather, they were men of late antiquity, mostly educated in a “Great Books” canon heavy on the classical philosophy — and the worldview of philosophers is often quite different from the general norms and presuppositions of their society as a whole. (Not that modern — by which I mean post-1600 — classicists have always recognized this; E.R. Dodds’s The Greeks and the Irrational is considered a seminal work of classical scholarship precisely because it undercuts a long tradition of taking the philosophers as representative of their culture rather than in conflict with it.)1 So the direct influence on early Christians wasn’t the world Fustel de Coulanges describes (which covers roughly the Greek Dark Ages through the Archaic period), but the texts of the period that came after, as interpreted by an even later era. It’s a bit like looking at our contemporary small-l liberals, who draw heavily on a tradition that rose out of Enlightenment philosophy, which in turn was an outgrowth of and/or reaction to the medieval and early modern worlds: they’re not not connected to all that, but Boethius is not going to be the most helpful context for reading Rorty. You should probably look at Locke instead.

So, setting aside chalcolithic warlords, what did this Greek philosophical tradition that educated Christians inherited and marinated in have to say about women? Well, still nothing good. Mitchell glosses classical philosophy’s main goal as “achiev[ing] self-mastery, self-sufficiency, immunity from the passions of the soul and body, and ultimately union with the source of all good.” In pursuit of these, philosophers elevated “soul over body, mind over matter, cosmos over chaos, culture over nature,” and ultimately nomos (law, custom, order) over physis (nature, especially in the sense of unplanned, uncontrolled, organic growth). And since the Greeks generally associated women with physis — one way2 of reading the Oresteia is as a story of the subjection of nature to law via the abandonment of hereditary rule’s public role for women as wives and queens, and a fragment of Sophocles describes Aphrodite as “called by many names…Death and the undecaying lie, she is the rage of madness” — this also necessarily implies the elevation of male over female. The Pre-Socratics consistently denigrated both sex and marriage: Pythagoras is said to have advised a man to marry only when “you want to lose what strength you have,” Parmenides called mating and birthing “cruel,” and Democritus said that a man who wants children should choose them from among his friends’ offspring to make sure he ends up with a good one.

Plato, perhaps surprisingly, actually comes across as more pro-woman, but only insofar as he sees souls as essentially sexless. The goal of philosophy, in his telling, is the ascent to world of the immaterial Forms, from which our bodies hold us back: in the Phaedo we read that “if we are ever to know anything absolutely, we must be free from the body and must behold the actual realities with the eye of the soul alone.” In the Symposium he describes eros as the desire for the Good (which is of course also the True and the Beautiful), but argues that the philosopher must ascend from the love of one person to the love of all beautiful things and ultimately of Beauty itself. The sort of love that leads to marriage, intercourse, and children is antithetical to philosophy; in the Phaedrus we read that “he who is not newly initiated, or has been corrupted, does not quickly rise from this world to that other world and to absolute beauty when he sees its namesake here, and so he does not revere it when he looks upon it, but gives himself up to pleasure and like a beast proceeds to lust and begetting.” Of course, Plato thinks that women are (at least in theory) as capable of philosophy as men — the speech he puts in Socrates’s mouth in the Symposium is framed as a lesson imparted to him by the prophetess Diotima — but because women are actually reincarnated cowardly souls implanted in weaker bodies due to their own innate inferiority, they generally find virtue and the philosophic ascent more difficult than do men. In short, if Plato disagrees with the Pre-Socratics’ general opinion that women were inferior to men, it’s only because he doesn’t think women are really women in any meaningful sense.

Aristotle is generally my favorite of the classical philosophers and the one who is by far the most positive about marriage and family.3 His anthropology includes a major role for sexual distinction, marriage, and procreation; he’s famously remembered for his observation in the Politics that man is a “political animal,” but in the Nichomachean Ethics he writes that “man is by nature a pairing creature even more than he is a political creature, inasmuch as the family is an earlier and more fundamental institution than the State.” He also praises the household division of labor and the way marriage unites the unique virtues of each sex to bring forth a more fully virtuous union. And yet despite all that, he inadvertently provides the groundwork for the other half of the “Greek” strain in Christian thought. He praises marriage, but his theory of categories and his theory of animal generation unexpectedly combine to make a case that sex doesn’t really matter.

Mitchell offers a good summary here, which I’m going to simplify further. In Aristotle’s account of reproduction, the male provides the “seed” and the female the matter. It isn’t quite the caricature of “woman as vessel for homunculus” that modern critics would make it, though certain later inheritors of Aristotle’s thought did take it that way; rather, it’s more like what a modern biologist would describe as male provision of genetic material to develop in a female epigenetic environment. The offspring then develops into a normal creature capable of creating seed (a male) or a defective one (a female). All the observed behavioral and physiological differences between men and women derive from this fundamental deformity: women are imperfect men, so they are more compassionate and cry more easily, are more deceptive and less forgiving, and so forth. Well, so far so good, aside from the fact that it’s not actually how babies are made, but the real problem is that this means that male and female don’t fit into Aristotle’s system of categories. He wrote an entire book about categories and if you care you can find a discussion of it here, but for our purposes it suffices to say that he defines a thing by the form (εἶδος) it shares with all others of its kind and the genus (γένος) that includes its form and all others. For example, when we say that Aristotle is a human being, an animal being, a living being, etc., “human being” is his form; “human” and “dog” are two separate forms within the genus “animal being.” But because Aristotle believes that the female is an incompletely-developed male, he can’t say that male and female are two different forms within the genus “human being.”4 Thus the differences between male and female are mere accidental properties, like a chair being made of wood as opposed to metal, with no bearing on the actual essence of the thing in question, but the human being qua human being is a man.

This was the philosophical tradition in which many of the Fathers of the Church were educated: people are basically just “human beings,” insofar as there are differences between men and women it’s mostly a matter of women being weak or defective men, and sexual distinction exists primarily or solely to ensure the perpetuation of the species. And weirdly enough, for a way of thinking about the world that’s more than two millennia old, it’s actually extremely recognizable: it’s modern feminism. Except that where Greek philosophy says that the differences between men and women are due to women being innately inferior, feminism says they’re due to society forcing women into an inferior role. Freedom from this oppression means escape back into being a pure “human being” — except that “human being” is defined after the male model, which in the modern West includes the political franchise, participation in the marketplace, and sexual disinhibition. Especially for the second wave, women’s liberation meant that women could do anything men could, ideally while wearing shoulder pads.

Now that women have by and large taken those corner offices, though, things have shifted and identifiably feminine modes of behavior are valorized. Instead of encouraging women to be as aggressive as a man, both men and women are now expected to take a collaborative, emotionally vulnerable, and caring approach to the world (which in practice usually ends up looking passive-aggressive). If Aristotle sees being a woman as a sort of congenital disability, like being born blind, feminists are divided between those who see it as a deliberate mutilation, like being blinded, and those who agree with the disability framing — but only for the social model of disability. It’s not that not-being-able-to-see is a problem, it’s just that our darn society is constructed with the assumption that everyone is sighted! Clearly we should just put Braille everywhere, which I guess in this terrible metaphor I shall now abandon would mean deciding things by consensus and having nice lactation rooms for Walmart cashiers or something.

So anyway, there’s Greek philosophy and why it was the misogynists who decided sex didn’t matter. Why don’t you tackle its ripples through Christianity?

John: You just made me think that somebody could write a fun history of the last few decades of feminism, framed as the transition from the 2000s-era “women are defective men” (and need to be more assertive, careerist, promiscuous, etc.), to the contemporary “men are defective women” (and need to sit quietly and fill out worksheets, submit to bureaucratic mandates, never speak up against social consensus, etc.). Proposed title: “From Penthouse to Longhouse.” Our credit card processor would drop us immediately.

But as you say, for the Greek philosophers it only went one direction, and what they primarily meant by it was that men were numinous and women were chthonic. At the same time, these philosophers were also extremely opposed to marriage, normal sexual intercourse, children, and family life. Mitchell does a good job of showing how these two different intellectual tendencies combined to form what he calls the “Greek” strain of early Christianity.

This includes all of what you might term “the weird stuff” — cults of perpetual celibacy, Origen castrating himself for the kingdom of heaven, Gnostics declaring that physical matter itself is shameful, über-Gnostics declaring that reproduction is a crime. There was a huge surge of this stuff in the earliest decades and centuries after Pentecost, fueled by apocalyptic expectation that the end of the world was coming any day now. It freaked out the pagans to no end. They thought it was unnatural. It is unnatural! A lot of it was eventually beaten back and subdued by the Church, but traces remain, and they impart to Christianity much of its enduring otherworldly flavor.

But this didn't just come out of Greek philosophy (the cultural marxism of its day), it also had a solid scriptural foundation. Mitchell, whose sympathies clearly lie more with the Hebrew side, is scrupulously fair about this. The Lord clearly tells the Sadducees that “in the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the angels of God in heaven.” Earlier in Matthew’s gospel He says “there be eunuchs which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake.” It’s not totally surprising that Origen took that a little bit too literally, or that he and other early Christian leaders laundered these passages into a full-spectrum attack on marriage and childrearing.

At its weirdest, some of this stuff got very weird indeed. St. Ambrose of Milan and Origen both claimed that the Virgin Birth took place so that Christ would not be defiled by any connection to sexual intercourse. Origen also believed in a two-step process of creation where individuals were first created as immaterial, sexless, perfectly rational souls, and only later given bodies as a consequence of the Fall. He allegorizes the “coats of skins” that Adam and Eve sewed for themselves after their expulsion from the Garden to physical bodies, and celebrated that death was the reverse of this process. Have you ever wondered why the Second Council of Constantinople issued an anathema condemning “those who believe the dead will rise as spheres”? It was an anti-Origen play! He thought that in death the entire physical being was sloughed off and left to decay, allowing the dead to rise as souls made of pure light — probably in spherical form, since the perfectly rational Sun and Moon and stars were spheres.5

Origen was condemned as a heretic, as were most of the Gnostics and a great many other holders of the weird, “Greek” views on sex and gender. The strongest exponent of these views who remained definitely within the church was the great seventh century theologian, St. Maximus the Confessor. Going toe-to-toe with Maximus is a daring thing for Mitchell to do, as he’s one of the more highly-regarded saints in the history of the Eastern Orthodox Church, but Mitchell is absolutely not having it when Maximus says that man’s purpose includes:

completely shaking off from nature, by means of a supremely dispassionate condition of divine virtue, the property of male and female, which in no way was linked to the original principle of the divine plan concerning human generation, so that he might be shown forth as and become solely a human being according to the divine plan, not divided by the designation of male and female... nor divided into the parts that now appear around him, thanks to that perfect union, as I said, with his own principle, according to which he exists.

This is, as Mitchell points out, dangerously close to Origen’s view in which maleness and femaleness are “coats of skins,” not part of God's original plan for the world but a consequence of the Fall of Man,6 to be shed in the world to come.

I won’t spend as long on the Hebrew Christian view, because it’s much closer to what you see in most other religions with their origins in agrarian societies. Marriage is valued, children and family life are valued, men and women are distinct and each have their roles, with men clearly in the lead. Clement of Alexandria goes so far as to say that “good husbands make good clergy.” All of this is very close to the human sociological baseline, and Mitchell argues that throughout the early centuries of Christianity this was the view held by a “silent majority” of believers, who eventually triumphed over the anti-family, anti-sexual-distinction Greek approach and relegated it to the monasteries and to the fringes.

So...what do we think of all of this? As a married man, I suppose my revealed preference is for the Hebrew approach, but like Mitchell I can’t deny that the Lord said those words that Origen and his crew latched onto, and He must have done so for a reason.

For me, much of the credibility of Christianity stems from the ways it’s occasionally inhuman. “Protect your friends and kill your enemies” is deeply wise, deeply human advice that every philosopher and sage since time immemorial has said at some point. “Love your enemies and bless those that curse you” is totally crazy advice, the kind of thing that comes from a madman or a god. But Christianity is full of stuff like that, and most of the history of Christian civilization is dominated by this uneasy tension, this halting set of accommodations and guilty compromises where everybody tries to take this stuff seriously, but at the same time not too seriously because then we’d all starve to death. We venerate kings and queens who sacrificed all their worldly status and possessions to live in monastic poverty, but we also venerate godly monarchs who raised armies to go punish the heathens. By and large, people understand that the world is a complicated place and that not everybody can be a schema monk, but they’re out there, reminding us by their example that we were made for something different.

I view the “weird” Christian takes on sex and gender in a similar sort of way. Everybody knows that it's great to have “thy wife [...] as a fruitful vine by the sides of thine house: thy children like olive plants round about thy table.” Well...okay, not everybody in America knows that, but we live in an unusually deranged and disordered society. In most places for most of human history, this was the most blindingly obvious thing in the world. And to have somebody come along and exalt perpetual virginity and say that male and female are not part of God’s plan but a division to be overcome, well that would be shocking.

But that shock can be salutary in several ways. Most people in most times and places have lived in clannish societies rife with cousin-marriage. Indeed, as you may recall from our review of The Ancient City, the Hellenistic world where the gospel was first preached was just such a society. It’s sobering to read over some of the early martyrologies, and count just how many of them were martyred by close relatives. In a world like that, the more anti-family aspects of the Christian message were probably a useful corrective, if not downright emancipatory. Does saying that make me a lib?

But I think the shock can be salutary for us too, even though we live in a society that has deviated from the golden mean in the opposite direction, and which in most respects needs to hear the other, “Hebrew” half of the message more. It’s salutary because it reminds us, like the monastics and the hermits and the holy fools remind us, that this [gestures around at our beautiful house] is not what we were made for, that we’re called on to transcend this merely human life and to become something terrifying and glorious instead.

Jane: Whoa, are you implying that my freshly mopped kitchen floor is not a foretaste of Heaven?

The intellectual history parts of this book are lots of fun, but what really interests me most are the practical implications. How should men and women relate to one another? Or, more accurately, how should husbands and wives relate? Because while people obviously have to encounter each other as beings that have sex (in the sense of being either male or female) before they can get married,7 there is a very particular relationship, covenant, and set of responsibilities implicit in a marriage. I ought to relate to my husband differently than I did to him before we were married, and definitely differently than I do to other men I’m not married to. But how, exactly?

The really important bits of Scripture here all use the image of the head, as in 1 Cor. 11:3, where St. Paul writes that “the head of every man is Christ, and the head of the woman is the man, and the head of Christ is God,” and in the passage from Ephesians 5 you quoted above, where he says that “the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church.” There’s a fair bit of discussion about what exactly the “head” is, which Mitchell summarizes nicely — the Greek is κεφαλή, which in addition to referring to the body part that sits on top of your neck can also be used to mean both “ruling power” and “source”8 — but the main point is the relational analogy, and for two thousand years that’s proven a very rich seam to mine in talking about marriage. If wife is to husband as Man is to Christ, as the Church is to Christ, as the Son is to the Father, then exploring those other relationships can help us understand what the husband-wife bond ought to look like. Toby Sumpter does a version of this in his book on marriage, No Mere Mortals, where he suggests that women look to the Psalms for a model of how the Church addresses the Lord:

How is the bride of Christ instructed to speak to her husband, Christ? The book of Psalms is an inspired script of possible options. What we find in the Psalms are many prayers of praise, respect, honor, remembering God’s greatness and salvation. Therefore, a wife should work hard to praise her husband, speak highly to him and about him, and thank him for his faithfulness, loyalty, hard work, paying the bills, and so on. This is what respect and honor do. Just as praise and thanksgiving fill the psalms, praise and thanksgiving should be on a wife’s lips regularly. Nevertheless, we also find Psalms of lament and sadness, one of which says something like, “Where have you been all day? Why have you not answered any of my texts? I’m surrounded by people in diapers. Will you not come speedily with chocolate ice cream and deliver me? (Trust me, it’s in the Hebrew.)

Mitchell chooses another one of these analogies, the idea that wife is to husband as Son is to Father. But rather than simply using it to illuminate the nature of marriage, he employs it to settle the debate between the Greek and Hebrew strains in Christianity once and for all. Recall that the Greek version “holds that male and female is a temporary imposition on human nature solely for the purpose of procreation, having nothing to do with the image of God and therefore impeding the process of theosis” while the Hebrew “believ[es] human nature to be complete in two sexes, both bearing the image of God, each expressing the image in its own way as God intended and declared ‘very good.’” These seem fundamentally irreconcilable, so which one is right? Well, Mitchell has already shown his cards, he’s coming down on the Hebrew side, and he argues that there is, in fact, a connection between the image of God in which we are created and our division into male and female.

His entire last chapter is devoted to this case, and I think it alone is worth the price of admission; there’s a lot going on, including a fair bit of political philosophy, so I’ll just try to sketch the outline. The basic approach is not to look at men and women and try to read our sexed characteristics back on God, but to look at how God appears in Scripture and then try to see how men and women might “image” the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This turns out to be surprisingly illuminating, and Mitchell gives a long list with a lot of citations: not much is said in the Gospels about the Holy Spirit, but the Father and Son are said to know and dwell in one another, to reveal one another, to honor and glorify one another, and to love one another (though the Father is said to love the Son more frequently than the other way around). But beyond that, the Father gives, knows, shows, teaches, sends, commands, empowers, sanctifies, and exalts the Son; the Son thanks, comes from, humbles himself before, obeys, does the will of, pleases, petitions, confesses, and returns to the Father. The Father is loving and giving, the Son thankful and obedient, but both are fully God and perfectly one.

This “peculiar kind of relationship…that is both ordered and equal based on one person being the self-giving source of a thanks-giving other” gets a name: Mitchell call it archy. Archy “admits no inequality, no imposition of will, no need for subjection, no subordination of any kind, being an order without suborder based on shared life, common interest, mutual concern, singular will, and reciprocal interaction.” Which all sounds great, but it’s pretty abstract, so he also offers a few examples of how it plays out in human life. The most immediately obvious is a father with his adult son: the father regards his son with pride and joy, and while the son is a grown man who is fully capable of doing things on his own he still values his father’s advice and is thankful to his father for all that he has and is. The two are equals now, in some important sense, but they still relate to one another in light of their roles in a way the father would never relate to another man who simply happened to be his son’s age.

But this isn’t a perfectly satisfying example, because part of the relationship is a memory of past inequality — I don’t think the fond undertone of “I used to wipe your butt” can ever be entirely absent — which doesn’t feature in most relationships between adults. Luckily, Mitchell offers a few more examples: there’s some discussion of the Church, of the ideal political order, and of any other head-and-body institution like a club. Of course very few human institutions ever function wholly archically — sometimes people are subordinated to others because of their natural or circumstantial inequality, and sometimes people must impose their will on others by force — but I think the most helpful example is that of a military unit, of which Mitchell writes:

Some small, elite units can function merely archically, with no inequality of competence and no need to pull rank or use force. But take away their archical arrangement and they cease to be “units.” To function as one, they must have one of their number to begin things, to give direction, to lead the way, and to commit himself to responsibility for the whole and give his life for it if necessary. That is the essence of archē.

So there’s Mitchell’s answer to St. Maximus: our division into male and female does partake of the image of God because it “images” the archical/eucharistic (self-giving/thanks-giving) relationship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Humans generally — male and female alike — behave archically toward creation and eucharistically toward God, just as Christ takes the archic role toward Man but the eucharistic role toward the Father; between the sexes, the husband takes the archic role and the wife the eucharistic.

I’m very struck by this way of thinking about things, especially the description of marriage as an ordered community based on mutual concern, shared life, and singular will but without inequality or subordination — and, let’s be fair, I’m even more struck by the image of our marriage as SEAL Team Six9 — but I’m a little hesitant to endorse it. Not because I disagree, and certainly not because of some internalized feminism “okay fine you need a leader for any ordered human activity but why can’t it be the woman?” kind of reason, but because being the archical head is a big ask! It’s one thing to describe this as the behavior of God, who is of course infinitely giving of Himself, and quite another for a woman, who is not called to shoulder this particular burden, to expect it of men.

John: I was also grateful for Mitchell’s profusion of examples in the final chapter, because it implicitly makes the point that most of us will be called upon to behave archically in some spheres and eucharistically in others. Consider the woman who organizes the volunteers at her local soup kitchen but is led by her husband. Or the man who directs his immediate family and then goes to work as a janitor. Or the staff sergeant in that elite military unit who takes responsibility for some of his brothers-in-arms but reports to the commander.

And all of this is very good, because of something I’ve complained before that Americans don’t understand: leading is practice for following, following is practice for leading, you cannot be a good leader if you aren’t a good follower, you cannot be a good follower if you aren’t a good leader. In our social relations we’re called upon to step into both rules, and sometimes to move fluidly between them (as when the boss leaves work and heads to soccer practice, where he’s the rookie on the team). We ought to rejoice at this, because human beings were made to play both the archic and the eucharistic roles. Adam was supposed to be the high priest of creation, ruling over other created beings, but for the purpose of leading them in a chorus of praise and thanksgiving towards God.

To get crassly utilitarian for a moment: the archic model of leadership is not only ontologically correct, but also highly effective. Christianity gave us an image of the Lord of All as servant of all, and in our own benighted time this has filtered down to…the corporate buzzword of “servant leadership.” Like all corporate buzzwords, it’s had almost every last bit of meaning squashed out of it. But if you can cut through the glitzy executive seminars, treating your place at the head as a call to self-giving kenosis turns out to be an effective way to motivate people as well as being the right thing to do.

As for your fear that this is a big thing to ask of men, well, it is a big thing, but it’s good for us. Men are made to take on intolerable tasks when asked to do so by women. It secretly makes us happy. When men don’t have enough burdens, they turn to porn and video games and other achievement-simulators. A lot of what we see today is the result of men being socialized not to lead, and women being socialized not to demand that men lead. It’s a mutually-destructive spiral, and we all need to do our part to break out of it. So yes, honey, I will open that jar for you.

Bonus, and shorter, Dodds: “On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex,” which you probably do too.

The correct way, incidentally.

These are probably not unrelated, although I maintain that the marriage-and-family aspects of Aristotle are a subset of the generally practical approach for which I appreciate him. As an example, Plato and Aristotle give roughly similar numbers for the ideal citizen population of a city: Plato says it should be exactly 5,040, because that has such a large number of divisors; Aristotle says about 5,000 because that’s how many gathered people can hear the unamplified voice of one speaker.

If anyone today paid attention to both modern chromosomal science and Aristotelian categories, however, that’s exactly what they would say. Do Thomists do this? This seems like the sort of thing Thomists would do.

A certain Methodius of Olympus trolled Origen by asking whether in the resurrection we would be “spherical, polygonal, cubical, or pyramidal.”

Yes, I also think this contradicts the plain language of Genesis, wherein Adam and Eve are described as male and female before eating of the tree. I don’t know how Origen and Maximus get around this, but I'm sure they have a clever argument.

Then they can have sex in the sense of, you know, having sex.

The Septuagint uses κεφαλή and ἀρχή interchangeably to translate Hebrew רֹאשׁ, rosh, which also means both “head” and “beginning” (as in Rosh Hashanah).

In this analogy, which of our children is Osama bin Laden? You know the answer.

Awesome work. Thank you.

I love that you all work so well together. I'm waiting for the book/tv show/movie which frames husband and wife as a team against the world, instead of a couple at odds with each other until the end of the story.

Been doing a bit of reading of late on adjacent subjects like Carl Truman's the Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self. You all might enjoy that work as it traces the modern view of self starting with the Greeks to the present.

As a husband and father, the most important lesson for me was to sacrifice my "needs" for the benefit of my wife and family. Well, that and deliberately structuring my house as a place that gives praise to our Savior and Creator. This fundamentally transforms the home for the better.

Thanks again.

This is very interesting.

I think either you or the author you review discounts one other strain of anti-family/marriage thought in ancient Greece. The Greeks lionized the public at the expense of the private. The private was selfish; it was the world outside citizenship. It was, by definition, the realm of women, children, and slaves.

Greek myth is full of sons that eat fathers and mothers who murder children; <a href="https://antoniustetrax.substack.com/p/on-the-strangeness-of-the-greeks">it equates sex with violence and family with disorder.</a> The polis had no place for the family; honor, order, and law existed in and because of the public realm of the citizen. The Spartans take this logic to an extreme, but an extreme that was in turn idealized by other Greeks.

The first volume of Paul Rahe's REPUBLICS: ANCIENT AND MODERN is especially good on this, and can be read as a stand alone work: https://amzn.to/4dnWpFv