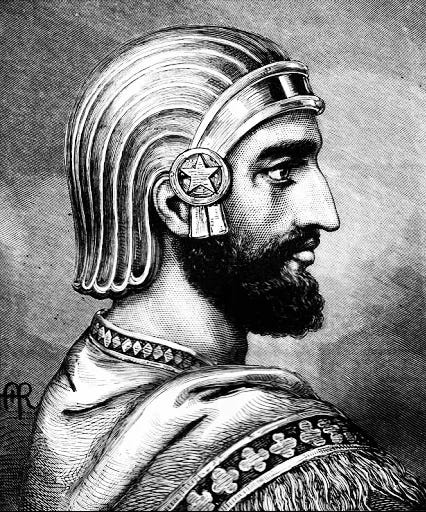

REVIEW: The Education of Cyrus, by Xenophon

The Education of Cyrus, Xenophon (trans. Wayne Ambler, Cornell University Press, 2001).

It is easier, given his nature, for a human being to rule all the other kinds of animals than to rule human beings. But when we reflected that there was Cyrus, a Persian, who acquired very many people, very many cities, and very many nations, all obedient to himself, we were thus compelled to change our mind to the view that ruling human beings does not belong among those tasks that are impossible… We know that Cyrus, at any rate, was willingly obeyed by some, even though they were distant from him by a journey of many days; by others, distant by a journey even of months; by others, who had never yet seen him; and by others, who knew quite well that they would never see him. Nevertheless, they were willing to submit to him.

I am not well-read in the classics. My excuse ultimately boils down to the same argument that all the classicists give for why you should be well-read in the classics: reading a book that has been widely admired for a very long time isn’t just reading a book, it’s entering into a “great conversation” taking place across the aeons. I feel awkward reading a book like that without knowing something about the commentaries on the book, all the people it has influenced, all the people who influenced it, the commentaries on the commentaries, and so on. It’s exhausting and overwhelming, and when I ignore all that and plunge ahead, I often don’t enjoy the book and then I feel dumb. A “great conversation” sounds nice, but only if you’re one of the participants and you actually get the inside jokes and references. Otherwise it’s as alienating and isolating as showing up to a party where you don’t know anybody, and where everybody else has already been chatting for a few thousand years.

I don’t remember who recommended Xenophon’s Cyropaedia to me or how it wound up on my reading list, but when it finally made its way to the top of my stack, I saw it and shuddered. How could I possibly appreciate this semi-fictionalized biography of the founder of the Persian Empire without first being familiar with Xenophon’s work as a mercenary for one of Cyrus the Great’s distant descendants? Or with all the ways he was riffing on and responding to the political philosophy of his frenemy Socrates? Or with the complicated politics of the Peloponnesian War, and the way that Xenophon, an Athenian exile and the original Sparta-boo, was actually writing PR for King Agesilaus II, but concealing it within a story about the exotic Persians?1 Or with how this book led to the creation of an entire major genre of books in the Middle Ages? Or with the most famous and subversive instance of that genre, Machiavelli’s The Prince, and with all the hundreds of subsequent works reacting and responding to that one?

You see the problem? One could very easily conclude that it would be impossible for me to appreciate this book. Fortunately, I ignored all that and read it anyway. No doubt I missed all kinds of subtle layers of meaning and nuance, but even read on a totally superficial level by an ignoramus, this book rocks.

The title has the word ‘education’ in it, but the book covers Cyrus’s entire life and reign, and only the first section concerns his education in the literal sense. That first section is very important to what comes next, though, so I’m going to dwell on it a bit. Cyrus, along with the other Persian boys of his social class, is being trained to lead. And so their education is centered around having lots of opportunities to judge, instruct, and coerce others; but also opportunities to serve and obey. If you’re old enough, you might remember when the education of the American leadership class worked this way too, but even those of you who are younger have seen vestiges of it in the bizarrely disproportionate weight given to extracurriculars in US college admissions.

Have you ever wondered about the origins of this? Bear with me for a minute. There’s a saying in the Psmith household, lifted from an NBC miniseries based on a James Clavell novel: “some things can only be done Tai-Pan to Tai-Pan.” (‘Tai-Pan’ is early-20th century Cantonese slang for the big boss of a mercantile concern.) There’s a fallacy often made by people not in the business world, where they assume that because the owner of a small company and a middle manager in a large one might command a similar number of people, that they therefore have anything at all in common. Nothing could be further from the truth. Generally speaking these two people could not be more different in their temperaments, worldviews, or values. In fact, the owner of a 10,000-person company has more in common with the owner of a 10-person company than he does with the vice president of a 100,000-person company with 10,000 people under him. The two owners are operating at vastly different scales, but both have experienced the dreadful weight of their own agency, both have felt the horror of having men under their command without the compensating balance of a superior capable of judging and correcting their actions. And by virtue of these facts and others like them, both are members of a select brotherhood that the middle-manager will never enter, no matter how exalted his title or how genuinely impressive his real-world power. There’s a level on which everybody still quietly knows this. It’s far easier for the founder of a tiny startup to get an audience with Elon Musk than for a senior vice president at Microsoft or Google to do the same. It’s just the Way of the World (TM).

None of this is unique to business, businesses are just the most common examples of monarchical organizations these days. It’s also true of armies and of bureaucracies, of churches and of whole nations. To lead is an experience like none other, and if you are being groomed to be the Tai-Pan of something great, the only way to get good at it is to practice at being Tai-Pan of something very small. This is not how our society thinks these days, but it’s how it used to think, and so this is the reason that Harvard has a vestigial interest in your presidency of the Lower Oswego Latinx Chess Confederacy. It was once assumed that having gravely assumed the mantle of the L.O.L.C.C. presidency you had been habituated into command, into rule, into the practice of adjudicating disputes amongst your inferiors, of rewarding the loyal, of forging alliances with other tiny Tai-Pans. Remember that time you struck a deal with the Greater Mackinac Asian Slam Poetry Brigade to beat up the Tarrytown BIPOC-Wargarmer Alliance before recess? The System knew that those were the experiences out of which leaders were forged, and so this whole section of the Common Application flops around, appendix-like, or like how our post-apocalyptic descendants will ritually polish black stones with their thumbs.

Anyway, young Cyrus is from a culture that gets this, so he and his classmates spend practically every waking moment being little Tai-Pans. They study in classrooms, receive military training,2 and shadow the magistrates in their official duties; but all of these official lessons are just the backdrop against which the real lessons are taking place. The boys have missions to accomplish, missions which they cannot possibly accomplish individually. So they have to learn to put together a team, to apportion responsibilities, and to judge merit in the aftermath. Anytime one of the boys commits an infraction,3 the adults ensure that he is judged by the others. All of this is carefully monitored, and boys who show partiality or favoritism, or who simply judge poorly, are savagely punished.4

The most common sort of mission is a hunt, the boys are constantly going on hunts, because: “it seems to them that hunting is the truest of the exercises that pertain to war.” This is obvious at the level of basic physical skills: while hunting they run, they ride, they follow tracks, they shoot, and they stab. But the military lessons imparted by hunting are not just physical, they’re also mental. They learn to “deceive wild boars with nets and trenches, and… deer with traps and snares.” To battle a lion, a bear, or a leopard on an equal footing would be suicide, and so by necessity the boys learn to surprise them, or exhaust them, or to terrify them with psychological warfare, doing everything in their power to find an unfair advantage or to create one from circumstances.5 As Cyrus’s father tells him years later: “We educated you to deceive and take advantage not among human beings but with wild animals, so that you not harm your friends in these matters either; yet, if ever a war should arise, so that you might not be unpracticed in them.”

There’s another reason that the boys constantly hunt wild animals, which is that it habituates them to hunger, sleep-deprivation, and extremes of heat and cold. When they depart on a hunt the boys are deliberately given too little food, and what they have is simple and bland (though that’s hardly an issue for those who “regularly use hunger as others use sauce”). Some of this is ascesis in the original Ancient Greek meaning of the word (ἄσκησις - “training”); by getting used to being tired and hungry and cold under controlled circumstances, they will be better at shrugging off these disadvantages when the stakes are higher.

But the real core of it lies in the phrase: “He did not think it was fitting for anyone to rule who was not better than his subjects.” Later, when they’ve reached manhood, the boys will oftentimes be called upon to share physical hardship with those they have been set over, and in that moment it is vital to this social order that they not be soft. “We must of necessity share with our slaves heat and cold, food and drink, and labor and sleep. In this sharing, however, we need first to try to appear better than they in regard to such.” Better in the sense of physically tougher, but also better in the sense of having achieved the absolute mastery of the will over any and all desires.6

Constant exposure to deprivation and hardship isn’t just supposed to improve their endurance, it’s also supposed to make them better at sneering at comforts.7 This is a society which believes that men are more easily destroyed by luxury than by hardship, and that it’s especially important that the leaders be seen to scorn luxury, for “whenever people see that he is moderate for whom it is especially possible to be insolent, then the weaker are more unwilling to do anything insolent in the open.”8 What I love about Xenophon is that unlike many Greek authors, who would deliver that line completely straight, he instead subverts (or at least balances) it with the observation that any kind of suffering is easier to bear when you’re in charge, and even easier when you’re bearing it in order to be seen to be bearing it.

This, then, is the education common to all the aristocrats of Persia, but even within this rarefied group, Cyrus is special. He is the son of the king, and the grandson of a neighboring king, and so naturally he receives every sort of favoritism. Fortunately, politics comes naturally to young Cyrus: when he is given extra food, he divides it up and gives it to his friends and his slaves. When he is on a hunt with others, he cheers on his peers, and takes care to recount each of their most impressive acts to the adults upon their return.9 He feels absolutely entitled to rule, but he also recognizes that to be a ruler is to be an artist or a craftsman whose tools are human beings.10

Of all Cyrus’s many qualities: willpower, strength, charisma, glibness, intelligence, handsomeness; Xenophon makes a point of emphasizing one in particular, and his choice might strike some readers as strange. It is this: “He did not run from being defeated into the refuge of not doing that in which he had been defeated.” Cyrus learned to love the feeling of failure, because failure means you’re facing a worthy challenge, failure means you haven’t set your sights too low, failure means you’ve encountered a stone hard enough to sharpen your own edge. Yes, it’s the exact opposite of the curse of the child prodigy, and it’s the key to Cyrus’s success. He doesn’t flee failure, he seeks it out, hungers for it, rushes towards it again and again, becoming a little scarier every time. He’s found a cognitive meta-tool, one of those secrets of the universe which, if you can actually internalize them, make you better at everything. Failure feels good to him rather than bad, is it any surprise he goes on to conquer the world?

And then…the most important single moment in Cyrus’s education, the moment when it becomes clear that he has actually set his sights appropriately high. He gets bored of the hunts. Cyrus deduces, correctly, that the hunts he is sent on, and all the other little missions, are contrived. Each is an exercise designed to impart a lesson, a little puzzle box constructed by a demiurge with a solution in mind. In this respect, they’re like the exercises in your math textbook. And like the exercises in your math textbook, getting good at them is very dangerous, because it can mislead and delude you into thinking that you’ve gotten good at math, when actually you’ve gotten good at the sorts of exercises that people put in textbooks.

When you’re taught from textbooks, you quickly learn a set of false lessons that are very useful for completing homework assignments but very bad in the real world. For example: all exercises in textbooks are solvable, all exercises in textbooks are worth solving (if you care about your grade), all exercises in textbooks are solvable by yourself, and all of the exercises are solvable using the techniques in the chapter you just read. But in the real world, the most important skills are not solving a quadratic by completing the square or whatever, the most important skills are: recognizing whether it’s possible to solve a given problem, recognizing whether solving it is worthwhile, figuring out who can help you with the task, and figuring out which tools can be brought to bear on it. The all-important meta-skills are not only left undeveloped by textbook exercises, they’re actively sabotaged and undermined. This is why so many people who got straight As in school never amount to anything.

The section covering his childhood and education concludes with a dialogue between Cyrus and his father Cambyses as the two ride together towards the border of Persia. Cambyses recapitulates and summarizes all of the lessons that Cyrus has been taught, and adds one extra super-secret leadership tip. Cyrus wants to know how to attract followers and keep their loyalty, and his father gives him a very good answer which is: just be great. Be the best at what you do. Be phenomenally effective at everything. People aren’t stupid, they want to follow a winner, so be the kind of guy who’s going to win over and over again, and if you aren’t that guy, then maybe choose a different career.

Cyrus asks and so Cambyses clarifies: no, he doesn’t mean be great at making speeches, or at crafting an image, or at appearing to be very good at things. He doesn’t mean attending “leadership seminars”, or getting an MBA, or joining a networking organization for “young leaders.” He means getting extremely good at the actual, workaday, object-level tasks of your trade: “There is no shorter road, son…to seeming to be prudent about such things…than becoming prudent about them.” In Cyrus’s case, this means tactics, logistics, personnel selection, drill, all the unglamorous parts of running an ancient army. People aren’t stupid. If they see that he is great at these things, they will flock to his banner. And then, one more ingredient, the final step: make it clear that you care about their welfare. “The road to it is the same as that one should take if he desires to be loved by his friends, for I think one must be evident doing good for them.”

There you have it. Two simple #lifehacks to winning undying loyalty: be the best in the world at what you do, and actually give a damn about the people under you. Our rulers could learn a thing or two from this book. So ends the education.11 The rest of this book, and the bulk of it, is Cyrus putting these lessons into practice by very rapidly conquering all of the Ancient Near East. It’s telegraphed well in advance that the final boss of this conquest will be the mighty Neo-Babylonian empire founded by Nebuchadnezzar,12 but before he takes them on Cyrus first has to grind levels by putting down an incipient rebellion by his grandfather’s Armenian vassals,13 then whipping the neighboring Chaldeans into line, then peeling away the allegiance of various Assyrian nobles, then defeating the Babylonians’ Greek allies and Egyptian mercenaries, before finally taking on the Great King in his Great City.

What I find unutterably charming about this section of the book is that the way Xenophon tracks Cyrus’s growing power level, the way he keeps score through all these conquests, is by the number of friends and lieutenants he picks up along the way.14 In this it resembles the classic Chinese novel Water Margin, or perhaps a certain sort of JRPG, where filling out the sprawling ensemble cast is the benchmark of progress, and the climactic showdown can only occur when the final henchman has been recruited to the hero’s party. In this it’s a little different from the classic Western forms of the hero’s journey, where allies may be recruited, but the main event is the maturation or reintegration of the hero himself.

Everywhere Cyrus goes, people are attracted to him: whether childhood friends now in possession of an independent power base, petty chieftains of independent nations, or even defeated enemies. They’re attracted to him because he’s obviously great, and he promptly turns around and showers them in love, riches, honors, and most important of all, his trust. At one point somebody criticizes Cyrus for this generosity and profligacy, pointing out that he has an army to feed and a war to win. Cyrus asks how much money might sit in his treasuries if he’d kept all the loot to himself, and the critic names some impossibly vast sum. Cyrus then smiles, and writes to all of his friends, asking them to send what money they can right away, as he’s fallen on hard times. The replies come back immediately, with many times more gold than the amount named, along with letters asking if he needs any more. Then he turns back to his foolish advisor: “You say I have no treasuries, but I make my friends wealthy, and my friends are my treasuries.”

So, this is a book about an education, what lessons can we take from it? What about lessons for those of us who have conquered Asia several times in Europa Universalis IV as practice for the real event? Here the book offers a mixed message. Cyrus is clearly made more effective by his training, his advisors, his meta-skills, and his friends; all things that any sufficiently motivated would-be conqueror could, in principle, acquire. But he is equally clearly the Child of Destiny: born with exceptional natural gifts and with a social position that offers him immense leverage. Everybody wants to be his friend because, as his father puts it, they are prudent men. They can see that he is going places, and that being the friend of Cyrus will bring them advantages. Part of that is his education and actions, yes, but part of it is his beauty, intelligence, physical strength, and royal lineage. Even his enemies recognize it, and it is one of these defeated enemies whose words might hold the key takeaway of this book:

“I asked the god what I could do to live out the rest of my life in the happiest way. And he answered me, ‘Knowing yourself, Croesus, you will pass through it happily.’ I was pleased on hearing the oracle, for I believed that he was granting me happiness, having assigned me the easiest thing. […] I believed that every human being knows himself, who he is. […] But when I was persuaded by the Assyrian king to campaign against you, I entered upon every risk. I got off safely, however, and sustained nothing evil…for when I came to know myself not to be competent to do battle with you, I went away safely. […] Then again recently…when all the kings around chose me to be their leader in the war, I undertook the generalship as if I were competent to become greatest, not knowing myself, as we now see, because I thought I was competent to make war against you. […] So not having known these things, I am justly punished. But now, Cyrus, I know myself. But does it seem to you that Apollo’s word will still be true, that knowing myself I will be happy? […]”

And Cyrus said, “Allow me to deliberate about this, Croesus. When I consider your previous happiness, I pity you and I grant already that you may have again the wife you had, as well as the daughters, the friends, the servants, and meals with which you used to live. But battles and wars I forbid to you.”

“By Zeus,” said Croesus, “then deliberate no longer to answer about my happiness. I will tell you that if you do for me what you say, I now have and shall lead the very life that others have believed to be most blessedly happy, and on which I agreed with them.”

And Cyrus said, “Who is it that has this blessedly happy life?”

“My wife, Cyrus,” he said. “She shared equally in all of my good, refined, and delightful things, but of my cares about how to secure these things, and of war and battle, she did not partake. You seem to be putting me in just the same condition in which I put her whom I loved more than any other human being. Consequently, I think I shall owe other tokens of gratitude to Apollo.”

“Know thyself,” the injunction of the Delphic oracle, is practically a cliché these days. But it was Xenophon who finally made me realize what it meant. It isn’t a romantic suggestion that you plumb the depths of your artistic soul like a Faustian hero, or engage in “me-search”, or spend infinite time in therapy. No, it’s actually pretty much the opposite. The original meaning of “know thyself” is: “figure out whether you are the Child of Destiny, and stop trying to act like one if you aren’t.” This directly contradicts much of our modern programming, and that’s a good thing. Nobody should aspire to be an NPC, but it’s okay not to be the main character. Not everybody can conquer the world. Not everybody can be Cyrus. But Cyrus needs and values his friends.

If you’re an American, then you’re already familiar with this trick. Most of our debates about the virtues and vices of other nations are just thinly-veiled attempts to “own” domestic political opponents.

If you’ve ever been a little boy, or the parent of a little boy, you know how true this is:

Now the mode of battle that has been shown to us is one that I see all human beings understand by nature, just as also the various other animals each know a certain mode of battle that they learn not from another but from nature. For example, the ox strikes with his horn, the horse with his hoof, the dog with his mouth, the boar with his tusk… Even when I was a boy, I used to seize a sword wherever I saw one, even though I did not learn how one must take hold of it from anywhere else, as I say, than from nature. I used to do this not because I was taught but even though I was opposed, just as there were also other things I was compelled to do by nature, though I was opposed by both my mother and father. And, yes, by Zeus, I used to strike with the sword everything I was able to without getting caught, for it was not only natural, like walking and running, but it also seemed to me to be pleasant in addition to being natural.

Not just explicit violations of the rules though: “they also judge cases of ingratitude, an accusation for which human beings hate each other very much but very rarely adjudicate; and they punish severely whomever they judge not to have repaid a favor he was able to repay.”

In one case, I was beaten because I did not judge correctly. The case was like this: A big boy with a little tunic took off the big tunic of a little boy, and he dressed him in his own tunic, while he himself put on that of the other. Now I, in judging it for them, recognized that it was better for both that each have the fitting tunic. Upon this the teacher beat me, saying that whenever I should be appointed judge of the fitting, I must do as I did; but when one must judge to whom the tunic belongs, then one must examine, he said, what is just possession.

Players of old-school tabletop role-playing games might be reminded of the distinction between “combat as sport” and “combat as war” or the parable of Tucker’s Kobolds.

Years later one of Cyrus’s classmates gives a long speech about how falling in love is optional — a real man can make himself love any woman he chooses, and conversely can restrain himself from loving any woman, no matter how desirable. All poetic references to being made a prisoner by love, or forced by love to do certain things, are excuses made by weaklings who wish to give into their desires. This is a message right in line with the most inhuman aspects of Greek philosophy, and to his credit Xenophon immediately subverts it by having the guy who delivers it immediately fall madly in love with his beautiful female captive.

One of the highest compliments ever paid to Cyrus is when an older mentor remarks of his posse that:

I saw them bearing labors and risks with enthusiasm, but now I see them bearing good things moderately. It seems to me, Cyrus, to be more difficult to find a man who bears good things nobly than one who bears evil things nobly, for the former infuse insolence in the many, but the latter infuse moderation in all.

Compare this to the American ruling class, which is also weirdly Spartan in its own way. The wealthiest Americans on average work a crazy number of hours, lead highly regimented lives, and avoid drugs. The difference is that whereas the Persian aristocracy does this as an example for the lower classes, the American aristocracy actively encourages the lower classes to consume themselves in cheap luxury and sensual dissipation.

The passage that recounts this also has this amazing line: “His readiness with words developed. But just as in the case of the body, the youthfulness of those who grow large while still young nevertheless shines through and betrays their few years.”

They then set off for their tents, and as they were going they remarked to each other with what a good memory Cyrus called them by name as he gave commands to all those he was putting into order. Now Cyrus was careful to do this, for it seemed to him to be amazing if each mere mechanic knows the names of the tools of his art, and a doctor knows the names of all the tools and drugs he uses, but a general should be so foolish as not to know the names of the leaders beneath him, and yet necessity compels him to use them as tools when he wishes to take something, guard something, inspire confidence, or cause fear. And if ever he should wish to honor someone, it seemed to him fitting to call him by name. Those who think they are known by their ruler seemed to him both to have a greater yearning to be seen doing something noble and to be more inclined to refrain from doing anything shameful.

There’s actually one other noteworthy bit of advice that Cambyses gives:

Above all else, remember for me never to delay providing provisions until need compels you; but when you are especially well off, then contrive before you are at a loss, for you will get more from whomever you ask if you do not seem to be in difficulty… be assured that you will be able to speak more persuasive words at just the moment when you are especially able to show that you are competent to do both good and harm.

This is decent enough advice, but what makes it especially fun is that Cambyses also applies it to the gods! Maybe it’s his own pagan spin on “God helps those who help themselves”, but Cyrus takes this advice and takes it a step further. He learns to interpret auguries himself so that he will never be at the mercy of priests. Then when he needs an omen, he performs the sacrifices, decides which of the entrails, the weather, the stars, and so on are pointing his way, loudly points them out, and ignores the rest.

Henrich notes in The Secret of our Success that divination can be an effective randomization strategy in certain sorts of game theoretic contests. But the true superpower is deciding on a case-by-case basis whether you’re going to act randomly, or just make everybody think you’re acting randomly.

Somewhere in the middle of In Xanadu, Dalrymple recounts an old Arab proverb that goes: “Trust a snake before a Jew, and a Jew before a Greek. But never trust an Armenian.” The tricksy Armenian ruler more than lives up to this reputation. But when Cyrus outwits and captures him, his son shows up to beg for his life, and what follows is one of the more philosophically charged exchanges in the entire book. They go multiple rounds, but by the end of it the Armenian crown prince has put Cyrus in a logical box as deftly as Socrates ever did to one of his interlocutors, and Cyrus lets the king off with a warning. The prince goes on to combat anti-Armenian stereotypes by serving Cyrus faithfully to the end of his days.

As any leader of a rapidly-scaling organization, Cyrus at one point has to switch from directly choosing people to choosing people who are good at choosing people.

He also understands the importance of getting rid of negative influences. Most people aren’t culture creators, they’ll go with the flow whether that leads towards excellence or towards something very dysfunctional, so weeding out the bad produces a double benefit. Or as Cyrus puts it:

Men, friends, know well that expunging the bad offers not only the benefit that the bad will be gone but also that, of those who remain, they who have already been filled with evil will be again cleansed of it, while the good, after seeing the bad dishonored, will cling to virtue with much greater heart.

The other eerily-relevant to 21st century office culture thing that Cyrus does is go on a rampage against remote work (seriously). He pioneers a “return-to-palace” policy, and gradually turns up the heat by first bestowing honors and communicating state secrets only to those who put in face time, and then eventually demoting or firing those who haven’t gotten the message. I don’t know how much process knowledge it takes to run the Achaemenid Empire, but I’m sure he had a good reason for it.

Appropriately enough, Water Margin was adapted (very loosely) into a JRPG series, Suidoken(by Japanese company Konami, so I assume "Suiodken" is the romanization of the Japanese rendering of a Chinese title). And you recruit a huge cast in each game.

I've typically slightly preferred Mrs. Psmith's reviews to yours (because of the subject matter) but this is a banger. Nice work.