REVIEW: The Albigensian Crusade, by Jonathan Sumption

The Albigensian Crusade, Jonathan Sumption (Faber & Faber, 1978).

People sometimes express surprise at the fact that I have kids, work an intense job at REDACTED, and still find time to read. The truth is it really isn’t that hard, I just don’t watch TV.1 No, if you want to see a busy guy, consider Jonathan Sumption (that’s the Right Honorable Lord Jonathan Sumption to you). Lord Sumption was a justice on the British Supreme Court for the past couple decades, and while doing that found time for his hobby of writing a magisterial, five-volume history of the Hundred Years War. According to Wikipedia, “Sumption speaks French and Italian fluently, and reads Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, Catalan and Latin.” He also has a bunch of kids. See? None of us have any excuse.

I don’t even have time to read a magisterial five-volume history of the Hundred Years War, let alone write one. But a little while ago I was in Albi and got more interested in the bloody and tragic history of that place, and learned that Sumption had written a book about it that might or might not be magisterial, but had the distinct advantage of not being five volumes long. I read it, and I’m glad I did, because this short history of one of the nastiest little wars in the entire Middle Ages has many weird and unexpected echoes with our own era, not to mention a lot to tell about the creation of the modern nation-state.

An Albigensian is an inhabitant of Albi, in the South of France. Before we get to that, though, we need to talk about the Cathars. An important rule of thumb in the history of Christianity is that heresies generally originate in the East and gradually spread to the West. I think this is mostly because, at least for the first thousand years or so, the vast majority of the population, GDP, and theological disputation was happening in the East. If you have theological ferment, you will have heresies, as assuredly as modifying software produces bugs and copying a cell’s DNA produces cancer. There were just a lot more people arguing about the nature of God in the East for a long time, and so given a constant error rate we should expect that most of the bad ideas come from there as well as most of the good ones. Now, why it is that this rule of thumb still holds true, despite the bulk of population and GDP moving to the West, is a very interesting question. Perhaps the legalistic Latin mind is just not as given to flights of fancy.

Whatever the case, the East was doing its usual thing and spitting out heresies, and two in particular are important to our story here. The first is dualism, which is a very old solution to the Problem of Evil, and which states that the forces of good and the forces of evil are evenly matched in some ontological sense. Many religions (for instance Zoroastrianism) are officially dualist. Christian dualism, on the other hand, has always been severely frowned upon if not outright condemned. Yet it’s also always been there, almost from the very start. I theorize that the dualist temptation arises again and again in Christianity because it “humanizes” an otherwise quite otherworldly faith, making it more like the stories and situations that human beings hear and encounter elsewhere.2

The second heresy is gnosticism, the belief that the physical world we all experience is an illusion, or a deception, or at least very much worse than the world of pure spirit. Once again, this is an important official element of religions like Buddhism, and once again it’s a tendency that Christianity has had to battle from the very start, probably because of some common, cross-cultural psychological quirk about human beings. Many modern Christians don’t actually realize that gnosticism is, technically speaking, totally heretical, because much modern Christianity is quite gnostic-inflected. But in the early days, and still today in some more traditionalist corners, Christianity is an earthy religion of bodies and physical substances and matter that is capable of being sanctified. For much more on all of this, read our review of Origen’s Revenge.

Anyway, relatively early in the history of Christianity, these two great ur-heresies flowed into one, like Godzilla and Mothra becoming a single monster that both flies and is radioactive. According to this grand synthesis, the false, illusory world of our physical reality is the domain of the forces of evil. The “god” of this world, often called the demiurge, is a diabolical figure, an anti-god that has trapped us all in prisons of flesh and blood. The real God is somewhere above and outside this reality, and our mission is to use secret knowledge, gnosis, to transcend to the spirit world. The guy who codified and turbo-charged this combined doctrine was a rich shipowner named Marcion (from the East, naturally), so you may sometimes see this heresy referred to as “Marcionism.”

If the physical world is the creation of an evil demiurge, then all physicality and physical matter must be irredeemably corrupt. In fact a much later Marcionist theologian actually used this as an argument for his views: “God is perfect; nothing in the world is perfect; therefore nothing in the world was made by God.” Consequently, the Marcionists practiced unbelievably extreme forms of ascetism to try to disconnect themselves from this corrupted world. They meditated and wore rags and occasionally starved themselves to death. Needless to say, having children was severely frowned upon, because it meant trapping new souls in the prison of reality. Critics of Marcionism accused them of endorsing sodomy as an alternative to normal sexual intercourse. The Marcionists also rejected the entire Old Testament on the grounds that the God of the Old Testament was actually the Devil, because only an evil being would do something as terrible as create the world.

The Marcionists were persecuted by the Roman authorities just as much as the Christians were, and this kept their numbers under control until by chance they spread to an empire with different laws. A wild-man from Persia named Mani, claimed by his followers to be a prophet and a magician, became deeply influenced by Marcion, traveled to India, returned to Persia, and created his own spin on Marcionism that incorporated elements of Buddhism and of his native Zoroastrianism. This combined religion became known as “Manicheanism,” and his followers refused to work normal jobs, serve in the military, or marry. Mani was promptly killed, but his teachings jumped back into the Eastern Roman Empire, and started spreading like a wildfire.

In the 8th century, Manicheanism (via a quick detour through a dualist Armenian group called the Paulicians) jumped the firebreak separating Asia from Europe and took off amongst the Bulgarian Slavs. Here, their champion was a priest named Bogomil, and his followers became the “Bogomils.” The English slang-term “buggery” is actually derived from the word “Bulgaria,” because of the old knock against the Marcionists. Did Bogomil in fact endorse buggery? It’s a little hard to say, but the “radical” Bogomils really got quite wild.3 The most extreme of them preached that performing disgusting or blasphemous acts was actually good, because it was a way of debasing and disrespecting our corrupted physical reality. It was also in Bulgaria that the word “Cathari” meaning “the purified ones” began to appear as an alternative name for this church.4

And it really was a church at this point, with their own bishops, and their own pope (living in secrecy in Constantinople), and their own church councils. Those councils settled important questions, like whether the radical Bogomils were going too far. Another important question was whether the god of the spiritual world and the god of the physical world were really equal in power or not (this question later led to a major schism among the Cathars, the more conventional and less dualistic position is sometimes called “monarchian dualism”5). A final important question concerned the multiple stages of Cathar initiation. Ever since the early days of Marcion, people had adapted to the truly fearsome physical deprivation required by his doctrine by constructing a two-tier system with a caste of “perfect ones” who followed all of the ascetic commandments, alongside a vast iceberg of supporters and fellow-travelers who professed the religion but were not yet fully initiated. In many ways this resembled a weird mirror image of Christian monasticism.6 But the exact relationship between the “perfecti” and the mass of believers had to be sorted out.

Another interesting thing about this shadow church, which will become important later, is that it was extremely popular with women of all ages and social classes. I have many theories as to why this might be, most of which I can’t say in polite company. For starters, women have a very different and more conflicted relationship with physicality and in particular with their own bodies than men do. It’s no coincidence that weird body image-related social contagions, from anorexia and bulimia to elective mastectomies, tend to spread fastest through adolescent girls. Puberty for both sexes involves a certain amount of body horror, but it’s worse for women, not least because it coincides with them turning into sex objects in the eyes of society. Across time and in almost every culture, adolescent girls experience dysphoric psychological maladies that spread like crazy through dense social networks.7 Perhaps we can view a religion like Catharism, which officially condemned both bodies and reproduction, as another culture-specific example of this.

Or maybe it’s simpler than that. It’s also just true that anytime social or cultural norms are shifting, women have usually been the drivers of it. Just as men are much more likely to conquer Asia, women are much more likely to drive widespread adoption of a new religion or new moral dispensation. This was true of Christianity itself, whose early spread was catalyzed by wealthy Roman matrons (most famously the widows of Antioch). It’s also true of wokeness in our own time, which achieved institutional entrenchment in 2020 largely due to female support, and continues to poll far better among women. Or consider the temperance movement, or the Great Awakening, or early communism, or the anti-slavery movement, or the rebirth of Orthodox Christianity in post-Soviet Russia, or really anything… The pattern is always the same: a few charismatic male leaders, and a large number of women making up the bulk of the support. Women are rarely moral entrepreneurs, but they act as something like the moral venture capitalists of the human race, wielding tremendous influence over which religions and revival movements succeed and which fail.

Anyway, the Cathar church survived underground in the Christian East for centuries, in an uneasy equilibrium with the society around it. Whenever it got too big, political or church authorities would launch crackdowns, but they never quite eliminated it. Then, a little while after the Great Schism, a combination of the Bogomils making their way slowly up the Balkan Peninsula into Hungary and Italian sea captains smuggling Cathar texts into the Western Mediterranean brought the faith to Western Europe. Here the situation was entirely different. There were no antibodies. It was an immune naive population. Not only did the Catholic West have no direct experience with Catharism, they practically had no experience with heresy since the Arians had been wiped out centuries earlier. There was no Inquisition. There was no tradition of high-stakes public theological debate like the Byzantines had. There wasn’t even a legal framework for state prosecution of heretics! Catharism hit Western Europe like smallpox hit the American Indians, and the stage was set for the bloodiest and most brutal war you’ve never heard of.

In the 12th century, Catharism was popping up all over Western Europe, but the one place it really took root and took hold and converted the entire society was in the South of France. Back then, the South of France was barely France. It had a different culture, spoke a different language called Occitan, and had a completely different social and economic organization from the rest of the country. In the North, around the city of Paris, geography contributed to the early emergence of a centralized nation state. Northern France is flat, there are very few defensible locations, but a lot of space for massive farms worked by hereditary serfs who are bound to the land. Cavalry were militarily dominant in this landscape, but a mounted knight is expensive to maintain, so the land was ruled by a small class of elite horsemen supported by a vast peasantry. Rebellions could be put down quickly and there weren’t many places for rebels to hole up or hide, so the nobility had relatively few rights against the king and the emerging bureaucracy. It wasn’t quite the hydraulic empire of Egypt or Northern China, but it was the closest thing to it on the European continent.

The part of the South known as Languedoc, by contrast, was isolated. It was isolated from the North by the enormous Massif Central, and it was isolated from itself by an undulating landscape of dense forests, narrow ravines, and hidden coves. The culture of the South was one of fiercely independent cities and towns, and a whole crazy kaleidoscope of minor nobles plotting against each other and against their suzerain, the Count of Toulouse. That’s right. They were hill people. Even the peasants had rights — Roman law still held sway through much of the South, which meant that tenant farmers had to be paid for their work, and could move to a different area if they didn’t like their local lord. Secluded places always hold onto the old ways for longer, and the great barbarian invasions that sloshed over Europe lost much of their violence by the time they made it over the mountains. Other signs of this: the Roman architecture that still stood in many a place (you can still go see it today), the Occitan language lacking much of the Germanic vocabulary that made it into French, and the locals cooking with olive oil rather than butter.

What is it about countries with a North/South division? The North is always flat, militaristic, centralized, bureaucratic, and efficient. The South is always languid, sensual, independent-minded, and seems like a nicer place to live. The descriptions of Northern and Southern France that I gave in the preceding paragraphs could apply, with very little modification, to Northern and Southern China. I know less about premodern Russia, but I’m told that it had a pretty similar dynamic, and that to this day all of the demographic and other social indicators are completely different (Southern Russia is poorer, more religious, and has more children and lower rates of alcoholism). And of course there’s the United States. That reminds me of another similarity — in all of these cases the South was conquered by the North and gradually lost the most salient bits of its regional identity. What is up with this pattern? Is it related in some way to climate, or to plate tectonics? Does it go the other way in the Southern Hemisphere? I need somebody to give me a grand unified theory of North/South dynamics in world history.

Back to France: it was to this magical Southern land of troubadours and Mediterranean breezes and bandits and high mountain fastnesses that the Cathar religion arrived from across the sea. It immediately started spreading like crazy, and since there wasn’t much in the way of state capacity, the forces of the Count of Toulouse or the Duke of Aquitaine could do little to contain it. Worse than that, the thousand petty barons and mayors and chieftains suddenly realized that tolerating the Cathars was a good way to thumb their noses at authority. It didn’t hurt that many of their wives and mothers and daughters had already converted by this point, and a few of the noblewomen had even become perfecti. With the state unable to act, the church tried to restore order. Successive popes sent missionaries and evangelists into the Languedoc, but got weak results. Finally, a council of the bishops of Southern France was called, and they decided to have a big public debate with the heretics, and the Catholics got totally “owned” by the Cathars, as the kids say. At this point, it became clear that the situation was not going to resolve itself without some more radical intervention.

Imagine how disturbing this must have been to a pious European noble. An alien, hostile, organized religion growing and spreading, not somewhere far away overseas, but right in the heart of Catholic Europe. Languedoc was a short sea voyage from Genoa, Rome, Barcelona, Valencia — practically the entire Western Mediterranean was next in line if the cancer continued to spread. The last straw for Pope Innocent III was when his friend and ambassador was assassinated under suspicious circumstances. So he excommunicated the Count of Toulouse, offered a plenary indulgence to anybody who invaded the South of France, and sent a letter to whomever he could reach which contained the lines: “Forward, soldiers of Christ! Forward, volunteers of the army of God! Go forth with the church’s cry of anguish ringing in your ears. Fill your souls with godly rage to avenge the insult done to the Lord.”

What does it mean to declare a Crusade against a piece of Christendom? Against a place where much of the population and almost the entire government was, ostensibly at least, still Catholic? Questions such as these gave pause to many potential volunteers, but they certainly did not give pause to the King of France. Crushing the independence of the South, subjugating it, disciplining it, forcing them to pay taxes and to speak proper French — these had been unattainable goals for the French crown for generations. But the Pope had just given his blessing to a total invasion with very liberal rules of engagement. It was an incredible opportunity. So within a few months, the king had mustered, equipped, and funded a large crusading army. In a practical sense, the Crusade against the Cathars was an operation by the French state, with the pope providing ideological support for actions against fellow Catholics that would never be tolerated under normal circumstances. And so this huge army marched southwards, aiming straight for the city of Toulouse, with murder and pillage on their minds, at which point the Count of Toulouse and overall target of the crusade did something incredibly aggravating.

He surrendered.

The Count was a canny man, and immediately discerned that only the most abject submission would result in his survival. He made zero attempt to prepare the defense of the city, and instead tearfully confessed that he had been led terribly astray by his advisors, had been much too soft on the heretics, and had failed to keep his vassals in line. He begged the pope for forgiveness, and then magnanimously offered to help lead the crusade of which he had previously been a target. This was all the pope wanted to hear, but it was infuriating to the king of France, who saw his excuse for invading and occupying a troublesome province slipping away. Meanwhile, the crusader army was milling around, getting bored and tired and cranky. Everybody had been preparing themselves for a climactic showdown in Toulouse, and when it evaporated, they weren’t sure what they were supposed to do next, like gamers suddenly deprived of their quest marker.

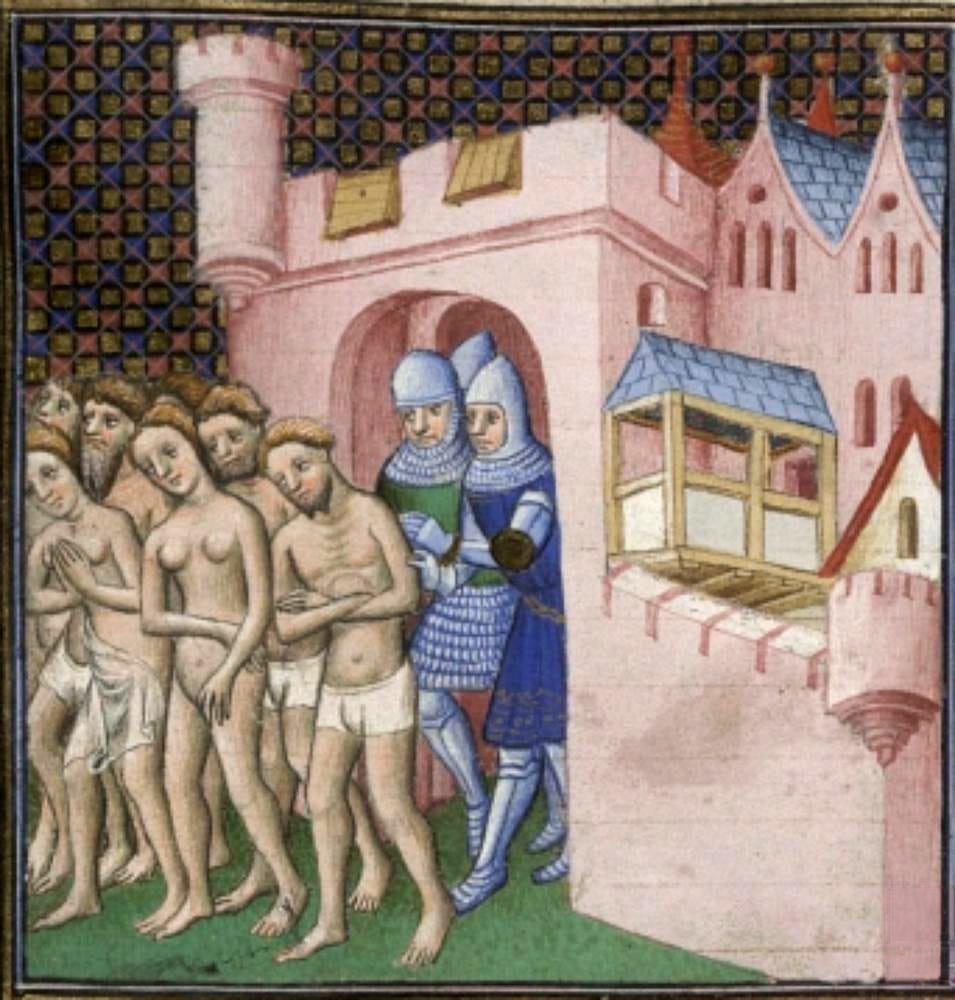

Maintaining an army in the field is expensive, so things could not remain in this state for long. There’s an alternate history where the great crusading army sheepishly melts back into the North of France or heads down to Spain to fight the Moors or something. But what happened instead was somebody told them that the city of Beziers was full of heretics, and suddenly the crusade was back on track and had an objective again. After conquering the city things got a little out of hand. Some stores were looted, some random civilians were murdered or raped. All normal siege stuff, and remember that this was a tired and cranky army. The thing is, human beings have two natural responses to realizing they’ve done something wrong. One is to feel very sorry, and the other is to decide that it was actually a good thing. The best way to sell yourself on the lie in the second case is to do a whole lot more of it, and so the occupation of Beziers suddenly morphed into an organized extermination of the city’s inhabitants. Have you ever heard the famous line: “Kill them all; God will recognize His own”? It actually comes from the commander of the crusader army at Beziers. The papal legate’s report to Rome is clinical and objective, merely noting that: “neither age, nor sex, nor status had been spared.”

After Beziers, a long war was inevitable. The Cathars, for one, now knew that the stakes were existential. But the complete destruction of one of the largest and most prosperous cities in the South,8 a city filled with faithful Catholics who were massacred as they clung to crucifixes and other sacred objects, meant that the Cathars suddenly had a lot of new allies. Practically the entire Southern nobility now took sides against the crusade, and everybody settled in for a long and grueling period of guerrilla warfare. The crusader army was too big to be defeated in the field, but too small to be everywhere at once, and so it roamed around the hills and valleys of Languedoc, leaving destruction in its wake but slowly bleeding out due to disease and ambushes. This continued for over a decade, with lots of confusing political scheming and minor nobles constantly switching sides, all ably related by Sumption. By the end of it, what had once been one of the most prosperous regions in Europe was a broken and desolate ruin.

One of the things that made this war so slow-moving and inconclusive was that in the eternal contest between offensive and defensive technologies, this was an era where defense had a clear upper hand. A well-built castle, competently garrisoned and with a clean water source, could hold out for a very, very long time against a superior foe. In fact, something I’ve gathered in bits and pieces, partly from this book and partly from others, is that the whole condition of siege warfare during this period is fascinating. The reason is that siege engineering — both building the castles and demolishing them — was viewed as “unchivalrous” by the warrior-aristocrats who served as commanders and mounted knights. But at the same time, the ability to perform competent siege operations was crucial. This created a weird, rare opening where a talented commoner could achieve insane wealth and prominence. The very best siege engineers operated on a strictly mercenary basis, flitting from war to war, building their reputations9 as they went and raking in tons of cash from kings and nobles who needed their skills. So putting it all together: there was a caste of people with an extremely narrow but in-demand technical skill who were able to bypass all credentialism and gatekeeping and make vast sums of money while they were at it. That’s right, siege engineers were the tech bros of the Middle Ages.

The war between the North and the South of France ended, as all civil wars between the North and the South of any country do, with the victory of the North. What followed was the systematic destruction of a civilization. First, the minor nobles who had been the backbone of Languedoc society were squeezed: “Estates…were crushed by the burden of royal taxation which now descended on them… They found their jurisdiction infringed, their castles confiscated or demolished, their subjects taxed, and themselves repeatedly cited before various courts and finally expelled from their home. Their destruction had been completed in less than a quarter of a century.” There was also massive brain drain — once every important decision governing provincial life was moved to Paris, the best and brightest scions of Languedoc society moved to the North to make their careers, and in doing so became Northerners and eventually brought the North back home with them. Linguistic change followed a similar pattern — the most ambitious young men learned French right away, because it was the language of administration and of power. Ambitious men often do well, and so French became associated with the upper class, and Occitan increasingly downmarket, until by the 19th century it was only spoken by the rural poor such as St, Bernadette Soubirous.

From today’s vantage, the borders of France might seem inevitable (in fact, the French have an entire pseudo-scientific theory about this). But on the eve of the crusade, the Massif Central might have seemed a more natural barrier than the Mediterranean or the Pyrenees. Culturally and linguistically, the people of Languedoc had more in common with their Spanish and Italian neighbors (remember that Occitan is much closer to Latin than French is, having escaped most of the Germanic influence). Economically, too, they were far more integrated with Western Mediterranean trade networks than they were with Northern Europe. It’s true that the King of France was the titular overlord of the Count of Toulouse, but the King of France was the titular ruler of a lot of places that aren’t part of France today.

And what of the Cathars? There’s a joke told by some Roman Catholics: “What’s the difference between a Dominican and a Jesuit? Well, the Dominicans were founded to combat the Albigensians and the Jesuits were founded to combat the Protestants. How many Albigensians do you know?” This joke is way too triumphalist, however, because the truth is that what the Dominicans are proudest of, their preaching and theologizing, had very little effect on the Cathars. In public debates, street evangelism, and overall missionary success, the Cathars continued to rack up win after win. To the extent that the Dominicans did defeat them, it was by staffing up the Inquisition — an organization founded in the wake of the Albigensian Crusade, for the express purpose of solving the Cathar problem once and for all. But here too, the Church can’t take much of the credit. The Languedoc Inquisition was to a great extent an operation of the French state, which funded, directed, and protected its agents as yet another instrument for the destruction of Occitan culture.

Be that as it may, the Inquisitors did their work well. Thousands of Cathar leaders were hunted down and publicly burned at the stake, the first really organized outbreak of religious violence in Western Europe. More important to the King of France, the Southern nobles who sheltered or tolerated Cathars were also investigated by the Inquisition and ruined. Within a few decades, the Cathar Church ceased to exist as an organized, hierarchical institution with coherent dogma. What believers remained tended to be marginal people living in marginal places, meeting in forests in the dead of night, espousing confused beliefs when caught and made to confess, more or less the same demographic that dabbled in witchcraft.

But is it possible that the Cathars got the last laugh? Centuries later, another austere and radical new religion swept through the South of France. Like the Cathars, it had a quasi-gnostic hatred of sensuality and ornament, and severe expectations regarding the personal holiness of its adherents. While its theology wasn’t dualistic, it wasn’t too far from the more monarchian strains of “moderate” Catharism. I’m speaking, of course, of the Calvinists. It’s a curious fact that the cities and towns which fully embraced the radical Reformation are almost perfectly correlated with the ones that had been Cathar strongholds centuries earlier. It’d be fun to ask the Cathars whether this is just a coincidence. But we can’t, because they are as dead as the civilization that once harbored them.

In our 2023 year end post I mentioned a much more painful sacrifice: I’ve largely given up computer games too.

You can also see it as injecting some excitement and drama and narrative stakes into the religion. A critic of Christianity might call it boring because the forces of evil are always and everywhere ultimately powerless. I don’t agree with this characterization, because the drama is taking place on a different level, namely the struggle towards sanctification that every living being engages in. But that might be too abstract for some. A much more immediate kind of drama is angels and demons duking it out on roughly equal terms, which is why you see this in all kinds of popular media, movie, video games, etc. Again, this is not an anomaly, it’s been present in Christian folk culture forever.

Thought not as wild as some even later Slavic adherents of Dualism/Gnosticism. The 18th century sect of the skoptsy interpreted the anti-physical, anti-reproduction message of Marcion as requiring castration for all true believers. Warning: the Wikipedia page has graphic pictures.

Anything you read about the Dualists, Gnostics, Marcionists, Manicheans, Paulicians, Bogomils, and Cathars is made considerably more confusing by the fact that tons of authors use these terms completely interchangeably (including ancient authors, and including the Dualists/Gnostics/Marcionists/Manicheans/Paulicians/Bogomils/Cathars themselves). It’s not even entirely wrong to do so, because there really is a continuous tradition here that all these groups are manifestations of.

Not to be confused with regular monarchiansim, which is a completely different Christological heresy.

Some important differences: the multiple tiers or layers of gnosticism are separated by secret initiation rituals in which you’re given secret knowledge. Christianity is a fully-public religion, and monks and nuns are not let in on any secret doctrines. Also, in Christianity not every believer is expected to have a monastic vocation, whereas in Catharism, everybody should eventually become one of the perfecti, some just haven’t made the jump yet. If Catharism resembles any modern religion, it’s actually Scientology. Multiple stages of initiation involving gradual revelation of secret knowledge, plus a theology and cosmology describing the world and our present life as a sort of prison.

More evidence for the theory that it’s partly related to distress brought on by sudden sexualization in the eyes of society: most of these psychological disturbances have a secondary effect of suppressing female biological characteristics. The transgenderism case is obvious, but did you know that a prolonged caloric deficit as produced by anorexia will often cause menstruation to cease?

The other large and prosperous city in the South that features prominently in the crusade was Carcassonne, which you may be familiar with if you like board games.

Some of them also developed weird rivalries with each other, and would carefully study how to demolish each others’ favorite castles.

Scotland (and also just Northern England to a lesser extent) is an interesting counterexample to your north/south problem. Scotland is clearly the South here, but also doesn't quite match the patterns other than wild and unruly.

Very cool to see this review. I’ve long thought of actually getting into Sumption’s 100YW series but it’s a big plunge to take!

Re: North/South splits:

-The thought occurs to me that Spain might be an example where the “hill tribe” part won out, as the south and east of Spain was always the more urbanized and populous part in earlier times. Those parts, of course, were also those conquered by the Moors, but over the course of centuries it was the combative nobles of the North who won out. These winners in turn became a lot more centralized and bureaucratic, but perhaps the long-term difficulties of the Spanish state after it finished the Reconquista are related to this starting point.

Britain is an example where the South/North characteristics are flipped, but the Not Hill Tribes part still wins.

In the Byzantine world, the split is more along the lines of coast vs interior. Islands and coastal zones tend to remain “civilized” places with durable links to Constantinople, while the interior is much more unstable and prone to becoming independent or getting overrun by newly-arrived tribes.