REVIEW: The Spirit of the Mountains, by Emma Bell Miles

The Spirit of the Mountains, Emma Bell Miles (James Pott & Company, 1905).

Jane and I once went to a restaurant where the food was northeastern Thai, the music and decor were Appalachian, and the owner was a Greek guy from central Arcadia. At first I was confused, but then it all came together in a moment and clicked. You’ve heard of “pan-Asian” dining, now meet a newer and more exciting trend. That’s right. It’s “pan-hill people.”

James C. Scott wrote an entire book about how hill people1 are pretty much the same in every time and place. They’re xenophobic, clannish, poorly educated, and violent. Or at least that’s the impression you probably have as a valley person,2 but they’re also resourceful, loyal, independent-minded, and brave. Scott argues that the reason the hill person phenotype recurs over and over in humanity is something akin to convergent evolution. It’s like how everything becomes a crab, or how “tree” is less of a phylogenetic category and more of a strategy. In the case of hill people, what’s being specifically selected for is ungovernability — the things that make hill people special, both the positive and the negative qualities, are things that make them hard to rule, conscript, and tax. I talked much, much more about this in one of the first book reviews I ever wrote, and you may want to read that before continuing if you want to have any idea what I’m talking about for the rest of this.

Scott’s book is mostly about a specific group of hill people in upland Southeast Asia, and he only gestures at this bigger-picture cross-cultural comparison. That’s too bad, because the book I’ve always really wanted is a comparative global history of hill people everywhere.3 Alas, as far as I can tell that book doesn’t exist, so I’ve had to satisfy myself with reading broadly and doing my own comparisons.

That brings us to this book, which is most unusual because it isn’t a book about hill people, but a book by a hill person. These are rare. Formal education isn’t highly valued in hill people cultures, and giving away information about your tribe is practically taboo. When we do get introspective looks at their own culture by a hill person, it’s usually in the final stages of that culture being assimilated by the valley people. For instance, we recently had a hill people US Senator do just this, followed by a different hill people US Senator doing the same thing. But Appalachia today is a far cry from Appalachia a hundred years ago.4 So I sat up and took notice when I spotted a memoir of an Appalachian woman with a publication date of 1905.

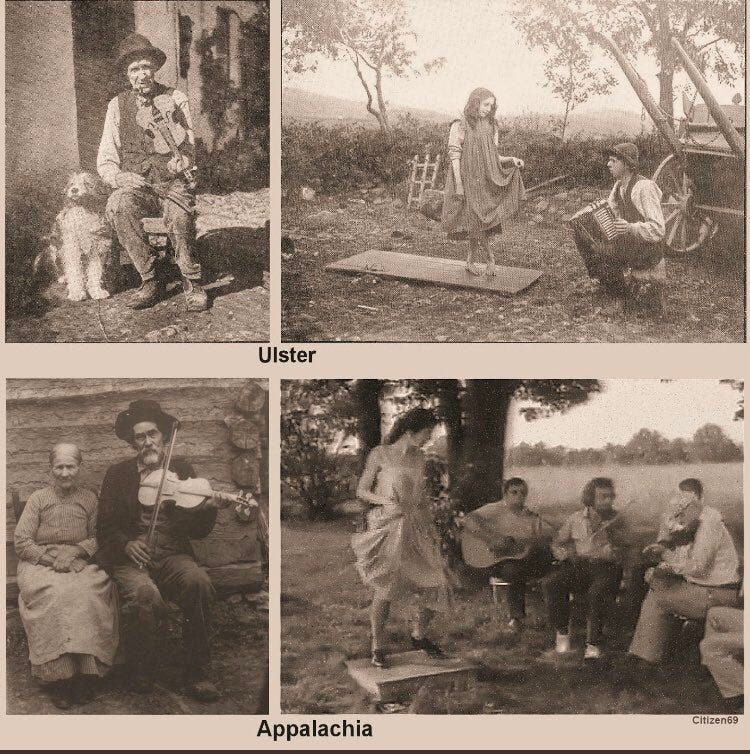

Yes, the people inhabiting the Appalachians were, and to some extent still are, classic hill people. If the (frequently true) stereotypes the rest of us have didn’t tip you off, perhaps their origins should. The Appalachians were peopled through a vast migration from the contested lands around the Scottish-English border and from Northern Ireland. One of the best ethnographies of these early settlers is David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed, and he describes the land of their origin like this:

The terrain is uneven—a stark succession of barren hills and deep valleys…Westward beyond Lake Windermere lies the Fell country, a sparsely settled mountain district with peaks rising to 3,000 feet, and high moorlands of almost lunar bleakness.

But that may not even be the dispositive part. If we take seriously Scott’s position that the thing that produces the hill people phenotype isn’t so much physical mountains as evolutionary pressure that’s selecting for ungovernability, then it’s easy to see how the border-dwellers got there. The border was the scene of generations of brutal warfare, followed by a heavy-handed royal effort to make the area legible and economically productive. The cultural response to this was the usual hill people package — clannishness, wariness of outsiders, strategic illiteracy and orality, wild and charismatic religious movements, etc. But it was something else too.

“Barbarians” of every sort tend to get a bad rap, and that’s especially true of the hill people subtype. There’s nothing intrinsic to the hill people cultural package that makes them especially brutal or violent.5 But the borderers, having marinated for centuries in conditions of brutality and violence, adopted a warrior culture (along with what evolutionary psychologists euphemistically refer to as a “fast life history strategy”). Fischer suggests that one of the things that attracted them to the Appalachians, besides the way that rugged and marginal land reminded them of where they came from, was the presence of many hostile American Indians with whom they could fight. The Appalachian settlers practiced a gruesome form of no-holds-barred wresting called “rough-and-tumble,” in which plucking out eyes, ripping off ears or nose, and castration of your opponent were not only permitted but encouraged. And the descendants of those Appalachian pioneers have always been the most enthusiastic participants in every one of America’s wars, frequently altering the balance of America’s political coalitions by switching to whichever party was in government when war was declared. General George Patton was of Appalachian extraction, and believed his ancestors literally hovered over him on the battlefield, writing in his memoirs that:

I was trembling with fear when suddenly I thought of my progenitors and seemed to see them in a cloud over the German lines looking at me. I became calm at once, and saying aloud, “It is time for another Patton to die,” called for volunteers and went forward to what I honestly believed was certain death.

There’s a lot more that you can read about these people, either in Albion’s Seed or in Scott Alexander’s excellent review of it. Of course today’s inhabitants of the Appalachians are much closer to valley people in their lifestyle and sensibilities — centuries of diffusion and osmosis with their neighbors (and changes in their material circumstances) have mellowed and softened them and sanded off some of their rough edges. But this book is about a point somewhere in the middle, a fleeting moment of twilight where the old culture still existed, but was clearly fading everywhere. As I said before: given the way hill people feel about books, especially books about themselves, it was the only moment in which something like this could have been written.

Emma Bell Miles had a short and tragic life. She was born and raised in Appalachia, moved to the big city for education and opportunity, but got homesick and returned to the mountains. This trajectory mirrors not only that of many Appalachians, but more broadly that of so many of the peripheral peoples living around the Roman and Chinese empires who were constantly diffusing back and forth across the imperial frontiers in response to local conditions. Unfortunately, in addition to her book learnin’, Miles also picked up one of the fundamental truths of the human experience: you can’t go home again. Her sojourn among the valley people changed her on the inside. Valley memes and valley values had burrowed deep into her soul, and she became an alien and an outcast to both cultures. She lived an unremarkable life, had an unhappy marriage, and died young.

When she first returned to the mountains, Miles got a job as a schoolteacher, which is a dead giveaway that despite having returned from the valley, she had imbibed its priorities and its morality, and now walked around unwittingly propagating them. Hill people have traditionally distrusted formal education, or as Miles puts it, “most of the children hereabout run free as the fawns and cubs that they often capture for playmates — as timid, as lithe and about as intellectual.” This is a common complaint and prejudice directed towards hill people. The stereotype is completely accurate, but as James Scott shows us, something deeper is going on under the surface here. Hill people are adapted to ungovernability, and they see “education” as a camouflaged vector for indoctrination and assimilation. Meanwhile, the educators sent up from the valleys are often true believers, but their bosses and funders often see their mission as…indoctrination and assimilation.

Sometimes this is obvious, as with the residential schools set up by countless colonizing powers throughout history. Sometimes it’s more subtle, as with universal public education or the Yale World Fellows program. And it’s those World Fellows that Emma Bell Miles really reminds me of — the best and the brightest from a peripheral culture, seduced into moving to the metropole, brainwashed without any violence or coercion, just exposed to the gentlest of peer pressure and mimetic desire, then released back among her people to contaminate their noosphere with imperial memes, slowly Ameriforming them. There’s nothing particularly sinister about this process, it’s something every empire in history has done, and in fact the American version of this ideological colonization is especially gentle and pull-based. It can be because of its overwhelming power.

Anyway, in 1905 the American Empire didn’t really exist yet, and this story was playing out not overseas, but within the territorial United States, as a process of national consolidation, ethnogenesis, and state formation. Miles is both an agent of the process and an astute observer of it, and she vividly describes several of the tricks that hill people, swamp people, and other barbarians have traditionally used to resist assimilation.

For instance, you may remember how Alexis de Tocqueville’s famous American travelogue emphasizes the ubiquity of what Edmund Burke called “little platoons.” Tocqueville talks at some length about how Americans are constantly organizing themselves into “intermediating institutions” — town meetings, churches, little league teams, friendly societies, and so on. But Tocqueville spent most of his time in New England; the picture in the mountains is different:

There is no such thing as a community of mountaineers. They are knit together, man to man, as friends, but not as a body of men. A community, be it settlement or metropolis, must revolve on some kind of axis, and must be held together by a host of intermediate ties coming between the family and the State, and these are not to be found in the mountains… between blood-relationship and the Federal Government no relations of master and servant, rich and poor, learned and ignorant, employer and employee, are interposed to bind society into a whole.

What’s going on? How does this help keep the government at bay? In fact, shouldn’t it be the opposite? Twentieth century political philosophers were constantly talking about how these mediating institutions shelter individuals from direct state power, and prevent the populace from degenerating into an atomized mass amenable to demagogic appeals. Heck, Hannah Arendt and Robert Nisbet both wrote entire books on this topic, so why are we now saying the opposite?

There’s another way to think about mediating institutions, which is as outsourced governance. Most rulers throughout history have lacked the state capacity to really enforce their edicts, so they fall back on private entities to fill the gap. Examples of this include everything from Chinese authorities granting family patriarchs the right and responsibility to punish disobedience, to medieval Christian polities indirectly ruling their Jewish communities through a network of collaborating elders, to the United States government implementing sanctions by telling friendly banks what they want and letting the banks do the actual regulating. Or just ask every imperialist or occupying power ever — the smart ones rule through local collaborators and proxies; the dumb ones disband the Ba’ath party and the Iraqi army, and then get chased out by an insurgency.

The way the more wild-eyed anarchist theorists talk about this is that all of these institutions domesticate human beings. They train us to conform and obey, they mold our very thoughts and character. A people formed in this way are just constitutionally easier to rule, and conversely when a people lacks any such organizations it’s harder for any government to maintain order. In fact, this is a big part of the anarchist answer to the problem of national defense — just be such an obviously difficult place to govern and administer, such an obvious black hole of money and resources, that no sensible invader wants to deal with you. It’s clever as far as it goes, but something fills the gap. Something always shows up to fill the gap, because there is a law of conservation of coercion. And in the case of the Appalachians, that something was the family clan:

Under the conditions of such a life it is inevitable that our social grouping falls naturally into tribes and clans. Most of the man-handlings and murders in the mountains are the result of family feuds, of perverted family affection… How beautiful this very clannishness may be in its right sphere — how loyal and generous and kindly a tie — is known only to those who have depended on it through many a crisis of want and illness and sorrow… feuds are part of the price we pay for the simplicity and beauty of mountain life… these ugly features are, under present conditions, the price of the tribal bond.

Oh yeah, the feuds, these people are full of feuds. If you remember the Hatfield-McCoy feud, that is just the tip of the iceberg of what these people got up to. Naturally, Albion’s Seed tries very hard to trace this feuding tradition back to the primeval feuding traditions of the Scotts-English border. There’s probably something to that, but we can also look at it structurally rather than genealogically — the inhabitants of the Appalachians were hill people, and hill people the world over endlessly feud. As Miles says, it’s the flip side of the non-WEIRDness,6 of the extreme familial loyalty that bonds people together in the absence of any other institutions.

As we know, another thing that goes along with clannishness, not just in Appalachia but the world over, is cousin marriage. I was not shocked to learn that the “Bell” that was Emma Bell Miles’ maiden name happened to be the family name of both her father and her mother. Classic hill people move. Or as she puts it:

All the children in the district are related by blood in one degree or another. Our roll-call includes Sally Mary and Cripple John’s Mary and Tan’s Mary, all bearing the same surname; and there is, besides, Aunt Rose Mary and Mary-Jo, living yon side the creek. There are the different branches of the Rogers family — Clay and Frank, Red Jim and Lyin’ Jim and Singin’ Jim and Black Jim Rogers — in this district, their kin intermarried until no man could write the pedigree or ascertain the exact relationship of their offspring to each other.

Here I started to write about the strategic uses of cousin marriage and indeterminate genealogy, before I realized that this whole book review skates dangerously close to what Scott Alexander describes as the universal experience of reading a David Friedman book:

Whenever I read a book by anyone other than David Friedman about a foreign culture, it sounds like “The X’wunda give their mother-in-law three cows every monsoon season, then pluck out their own eyes as a sacrifice to Humunga, the Volcano God”.

And whenever I read David Friedman, it sounds like “The X’wunda ensure positive-sum intergenerational trade by a market system in which everyone pays the efficient price for continued economic relationships with their spouse’s clan; they demonstrate their honesty with a costly signal of self-mutilation that creates common knowledge of belief in a faith whose priests are able to arbitrate financial disputes.”

So I’m going to stop doing that, or at least confine it to footnotes, because I fear I’m giving you the wrong impression of what this book is about. It isn’t an anthropological analysis of how mountain people evade the taxman; it’s a deeply sympathetic portrait of a very alien culture that was midway through the process of evaporating. And it’s a vibe. Roughly the vibe of this twitter account. There’s lost Indian silver7 and mountaineers who go to their graves refusing to divulge the location of their secret stash. There’s “Big Meeting” church revivals and muttering old women with herbs.8 And there’s ghosts. Oh my goodness, the ghosts are everywhere.

The climax of one chapter is a ghost story about a spectral crone who begins haunting a man’s family and ruining his life. He begs her to relent, begs her to tell him what he did that brought down her wrath, and every time he asks she tells him a different, nonsensical story, then drives him out of the house with peals of horrible screeching laughter. She begins to possess the whole house, she views his family as “hers,” she even does them occasional minor favors, but mostly she’s a nightmare. In desperation they convoke a prayer meeting in their living room, but the spirit is too strong and disrupts the meeting with blood-chilling and highly personalized threats against each of the participants. Finally, one day she kills the man she haunts. He’s found dead, heart stopped, terrified expression on his face. After that the spectral activity all stops. There is no explanation. Everybody shrugs. Sometimes things like that just happen.

The mountaineers carry that same fatalism to every aspect of their lives. In their grimness and use of litotes, they sometimes resemble the heroes of Norse epics. Here’s Miles again:

A man born and bred in a vast wild land nearly always becomes a fatalist. He learns to see Nature not as a thing of fields and brooks, friendly to man and docile beneath his hand, but as a world of depths and heights and distances illimitable, of which he is but a tiny part. He feels himself carried in the vast sweep of forces too vast for comprehension, forces variously at war, out of which are the issues of life and death, but in which the Order, the Right must certainly prevail. This is the beginning of his faith as he had it from his fathers; from hence is his courage and his independence. Inevitably he comes to feel, with a sort of proud humility, that he has no part or lot in the control of the universe save as he allies himself, by prayer and obedience, with the Order that rules.

Hence this is to him the whole value of prayer: his wrestlings with the spirit are all undertaken with a view to placing himself in the right attitude; his prayers are almost never mere requests to be granted; he will not cheapen his religion to a scheme for getting what he wants. The conversion of a near friend or a relative is often prayed for especially, and sometimes the recovery of one sick unto death, ‘if it be Thy will’… but with a few exceptions of this sort, it is not customary to pray for temporal benefits at all.

Maybe the saddest manifestation of that fatalism is its application to relations between the sexes. The mountaineers correctly understood that men and women are made for different things, but viewed the gulf as permanent, unbridgeable, and fundamentally antagonistic. Miles’ own marriage was bitterly unhappy, and it’s hard not to pick up a note of autobiography in her writing on men and women in mountaineer culture more broadly. I’m going to quote an extended passage here; partly because it’s hard to get her point across with an excerpt, and partly…for more sentimental reasons. These are the forgotten words of a forgotten woman, writing about a forgotten world (the modern reprint is literally published by a company called Forgotten Books). Reading it feels like giving her ghost a chance to touch the world again, and after spending a couple hundred pages with her, I want to do her this favor:

At twenty the mountain woman is old in all that makes a woman old — toil, sorrow, childbearing, loneliness and pitiful want. She knows the weight not only of her own years; she has dwelt since childhood in the shadow of centuries gone. The house she lives in is nearly always old — that is to say, a house with a history, a house thronged with memories of other lives. Her new carpet even, so gay on the rude puncheons, was made of old clothes and scraps of cloth. Who wove the cloth? It was woven on her grandmother’s loom. Yes, and she knows who built the loom. The marks of his simple tools are on its timbers still. Into her pretty patchwork she puts her babies’ outgrown frocks, mingling their bright hues with the garments of a dead mother or sister, setting the pattern together finally with the white in which she was married, or the calico she wore to play-parties when a girl. Perhaps she keeps her butter in a cedar keeler or pigeon that her grandfather made. At all events she churns it in a home-made churn. Her door swings on huge wooden hinges. Who made them? In what fray was the oak latch dented and split, and who mended it with a scrap of iron? How many feet have worn down the middle of the doorstep-stone! How many hearth-fires have sent their smoke in blue acrid puffs to darken the rafters! How many storms have beaten the hand-cleft shingles of the roof and strained at the mortised joints of its timbers!

Thus it comes that early in childhood she grows into dim consciousness of the vastness of human experience and the nobility of it. She learns to look upon the common human lot as a high calling. She gains the courage of the fatalist; the surety that nothing can happen which has not happened before; that, whatever she may be called upon to endure, she will yet know that others have undergone its like over and over again. Her lot is inevitably one of service and of suffering, and refines only as it is meekly and sweetly borne. For this reason she is never quite commonplace. To her mind nothing is trivial, all things being great with a meaning of divine purpose. And if as a corollary of this belief she is given to an absurd faith in petty signs and omens, who is to laugh at her?

Is it sickness? How many have lain in agony unto death on her old four-posted bed! Has her husband ill-treated her? She can endure without answering back. She has heard her elders tell of so many young husbands! Her dead babe? So many born here have slept and laughed for a time beside the hearth and dropped from the current of life!

She has heard the stories of everything in the house, from the brown and cracked old cups and bowls to the roof-beams themselves, until they have become her literature. From them she borrows a sublime silent courage and patience in the hour of trial. From their tragedies she learns, too, a sense of the immanent supernatural. It is almost as if they were haunted by audible and visible ghosts. Who would not fear to sit alone with old furniture that bears marks of blows, stains of blood and tears? They are friendly, too. They stand about her with the sympathy of like experience in times of distress and grief. This is one of the reasons why a mountain woman usually shows a disproportionate reluctance to selling her spinning-wheel or four-poster, even though the price offered be a bribe beyond imagining to one who sees whole dollars every day.

Few of these things become part of the man’s life. Men do not live in the house. They commonly come in to eat and sleep, but their life is outdoors, foot-loose in the new forest or on the farm that renews itself crop by crop. His is the high daring and merciless recklessness of youth and the characteristic grim humor of the American, these though he live to be a hundred. Heartily, then, he conquers his chosen bit of wilderness, and heartily begets and rules his tribe, fighting and praying alike fearlessly and exultantly. Let the woman’s part be to preserve tradition. His are the adventures of which future ballads will be sung. He is tempted to eagle flights across the valleys. For him is the excitement of fighting and journeying, trading, drinking and hunting, of wild rides and nights of danger. To the woman, in place of these, are long nights of anxious watching by the sick, or of awaiting in dreary discomfort the uncertain result of an expedition in search of provender or game. The man bears his occasional days of pain with fortitude such as a brave lad might display, but he never learns the meaning of resignation. The woman belongs to the race, to the old people. He is a part of the young nation. His first songs are yodels. Then he learns dance tunes, and songs of hunting and fighting and drinking, and couplets of terse, quaint fun. It is over the loom and the knitting that old ballads are dreamily, endlessly crooned…

Thus a rift is set between the sexes at babyhood that widens with the passing of the years, a rift that is never closed even by the daily interdependence of a poor man’s partnership with his wife. Rare is a separation of a married couple in the mountains; the bond of perfect sympathy is rarer. The difference is one of mental training and standpoint rather than the more serious one of unlike character, or marriage would be impossible. But difference there certainly is. Man and woman, although they be twenty years married — although in twenty years there has not been one hour in which one has not been immediately necessary to the welfare of the other — still must needs regard each other wonderingly, with a prejudice that takes the form of a mild, half-amused contempt for one another’s opinions and desires. The pathos of the situation is none the less terrible because unconscious. They are so silent. They know so pathetically little of each other’s lives.

Of course, the woman’s experience is the deeper; the man’s gain is in the breadth of outlook. His ambition leads him to make drain after drain on the strength of his silent, wingless mate. Her position means sacrifice, sacrifice, and ever sacrifice, for her man first, and then for her sons.

What I find haunting about this passage is that buried underneath all the layers of bitterness, resignation, and wistfulness, there’s one more emotion at work here: guardedness. To be a hill person is to be ungovernable by nature, to hide your thoughts, hide yourself, hide the things you value from those who want to tax you or conscript you or drag you away and put you to work building a palace for some far-away king. I did not expect to find the bristling paranoia aimed at government officials leeching into the marital bond as well. There’s something very disturbing about this, about those overwhelming clan and familial structures that act as cement for this society turning out to be composed of individuals who remain unknowable and illegible to one another.

I don’t know whether Miles’ experience is representative of all hill people, or even of everybody in turn-of-the-century Appalachia. But a version of the phenomenon she describes is too familiar. So much of the consolation of having a family is precisely that it can be a shelter against whatever deranged mode of social interaction dominates your culture — whether that’s unchecked market forces, overweening ideology, or (as for hill people) a heavily-armed truce in the Hobbesian war of all against all. But the paradox is that that benefit is inaccessible unless you let your guard down and commit totally, in a way that would get you slaughtered by a stranger.9 It’s a mode of relation that’s definitionally unscalable this side of the grave, but I’ve never known a happy person who didn’t have it.

I’m going to use “hill people” throughout this review as a synecdoche for hill people, swamp people, inaccessible-cove people, and all the other “inner barbarians” who for reasons of geography and cultural evolution are able to keep the bureaucrat, taxman, and conscription officer at bay. Similarly, “valley people” is everybody like you and me — thoroughly domesticated by the state, live in walled city, go to WINE BAR with ‘gf’, etc.

If you’re reading this Substack, you are statistically almost certain to be a valley person.

And the book Jane wants is that but for horse-culture steppe nomads. Come on, tell me it isn’t a crime that there’s no comparative analysis of the Mongols and the Comanches!

A lot of the reason this changed is that the Federal government made legibility taste sweet. James C. Scott talks a lot about how people resist government-issued identities out of fear of oppression, but it’s easier to get people to register themselves at a government office when they’re registering for welfare. Rural electrification and the Tennessee Valley Authority are what finally brought this troublesome region to heel. There’s a lesson for future conquerors there…

That said, a high proportion of hill people have incorporated things like cattle-rustling and kidnapping into their economic base.

As a one-sentence summary of non-WEIRDness you could do worse than this line from the book: “A man who would be shocked at swearing or Sabbath-breaking may make light of killing an enemy who has robbed or insulted one of his kin.”

She actually talks a lot about the Indians, and makes some sweeping cross-cultural comparisons of her own. At one point she notes that the public presentation of the mountaineer: narrow, superstitious, generous, dignified, laconic; is much like that of the Indian brave. She goes on to speculate that the environmental condition of the hills created both. Prior art for James C. Scott!

Joseph Henrich, whose books Jane has reviewed here and here, has a bit about how soothsaying, auguries, and the casting of lots can be seen as a strategy for committing to randomized decision-making, which is optimal in certain game theoretic setups. The extreme superstitiousness of the Appalachians, which is mirrored in a lot of other hill people, got me wondering if superstition in general might be an individual-level version of that. If your beliefs about the supernatural make your actions less predictable, that can only be good for your ungovernability.

When people complain about modernity and/or the libs unsustainably expanding our circles of concern and erasing the in-group/out-group distinction, it’s usually in the direction of treating strangers too well. But I am more concerned with the way it’s brought legal and/or market mechanisms into the domestic sphere. Everything from pre-nups, to separate bank accounts, to enumerations of rights and expectations. These are reasonable attitudes to bring when dealing with a stranger and very suboptimal ways to relate to your spouse or family members.

I liked both this and the Scott book review, but only in the sense that any news is better than no news, with respect to hill people. It opens a conversation. Both books (from the reviews ...) read to me like poll-tested missives about noble savages, ala Jared Diamond on tribes in New Guinea, or Scott on the border regions of Thailand, Burma, and Laos, for blank slate reader markets who want to read about human versions of zoo animals. Yes, those tribal denizens are so intelligent! And so on. I also perceive that both accts are deeply Anglo, and the Anglo world hardly has hills, except for Scotland (and of course, Appalachians are often Scottish), and the Scottish Highlands story is an old sad one, pickled and canned. To contrast, the hill peoples of the Alps, the Pyrenees, Peru and Afghanistan (Nepal!) are uncanned and open with histories and influences up to the present day. What they're not, is Anglo. And so few of them ever emigrated to the USA, so they're not recognizable on an American street, so books about them don't sell. The general suppression of Germanic culture in the USA that dates from the end of WWI to the present day ensures that Alpine culture becomes zoology not anthropology. Still, there's no explanation of phenomena like Swiss "armed neutrality" or anarchism (that grows in the 19th century with Russian and Swiss [William Tell] heroes) without reference to hill culture as an ethical norm. Even Israeli military doctrine draws on hill culture, because its military and its civic education draws so deeply on the Swiss example. I'm only focusing on the Swiss example because that's what I know, as my dad's side of the family is from Nidwalden, above Lucerne on the lake. An uncle of mine used to giggle that Lucerne in the 1700s forbade its women from marrying anyone from our canton because of its lawlessness. Shortly before Switzerland was founded (1291), our canton was excommunicated from the Catholic church for laying siege to the Einsiedeln Benedictine monastary. Had Schiller not conquered cultural Germany with his romantic era account of William Tell, we would hardly be known but for Swiss historians. It's not a matter of pride to me, however, nor to Switzerland, that the bloodthirstyness of hill culture as reflected in Swiss mercenary practice (not taking prisoners, mutilating bodies, threatening pillage for ransom, and so on) infected many military traditions with excess ferocity. A large part of Zwingli's Reform Protestantism was a rejection of mercenary life, which he failed to expunge from Switzerland because it brought in too much income to communities in place of taxes. It's also silly to call us clannish, since as successful mercenaries (and in the French Alps, as watchmakers), the hill people refreshed their culture with the booty, women, and profit of surrounding lands, while retaining their "ungoverned" character. It's also not at all the case that all hill people indulged in feuds -- the Scottish example may hold in Afghanistan, but certainly not in Switzerland (I don't know the Pyrenees case, but perhaps not there too -- did it hold in Peru too?). Again, the limited focus teaches far less that it suggests.

"Come on, tell me it isn’t a crime that there’s no comparative analysis of the Mongols and the Comanches!"

The ACOUP blog does a bit of this, when it looks at how similar the Dothraki from Game of Thrones are to either of them (Spoiler - not very!)

https://acoup.blog/2020/12/04/collections-that-dothraki-horde-part-i-barbarian-couture/