REVIEW: Against the Grain, by James C. Scott

Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, James C. Scott (Yale University Press, 2017).

Okay, stop me if you’ve heard this one already. So, there are these hunter-gatherers, right, and one of the things they like to gather, while they’re roaming around the hilly flanks of Anatolia following herds of gazelles, is the large, carbohydrate-rich seeds of local grasses. Then one day some bright soul gets the idea of planting the seeds on purpose, people selectively replant the ones that have exciting mutations like “have really big seeds” and “don’t shatter your stalk and scatter your really big seeds everywhere when they’re ripe, just hang out and wait to be reaped,” and they all start staying in one place to tend their fields. They quickly discover that agriculture can create a lot more calories than foraging, so all of a sudden they have a nice surplus that can go towards supporting non-food-producing specialists like dedicated craftsmen, priests, bureaucrats (but I repeat myself) and kings to expedite and organize all that agricultural labor, and, hey presto! you have civilization.

Oh, cool, you read Guns, Germs, and Steel in high school too?

Only James C. Scott is here to tell you that’s not how it happened. And while you might be excused for thinking (especially if you’ve read our review of The Art of Not Being Governed) that this is Scott doing his contrarian “ooh, look, I’m turning the accepted narrative on its head” thing, you would be wrong. (Don’t worry, though, we definitely will get to the point where he does that.) He’s just offering a summary of the new scholarly consensus: the transition from mobile bands of hunter-gatherers to sedentary agriculturalists didn’t follow that neat logical progression, and it was far patchier, more tenuous, and more bidirectional than generally assumed. In fact, practically since the moment in the late 1920s that V. Gordon Childe coined the term “Neolithic revolution,” archaeological evidence has been accumulating that complicates every aspect of the story I just told you, from agriculture to sedentism to state formation.

To begin with, what constitutes agriculture? Back in the 1960s, paleobotanist Jack Harlan used a flint sickle to harvest enough wild Anatolian wheat in just three weeks to feed a family for an entire year. Now, we can probably agree that just harvesting a stand of wild wheat and storing the grain doesn’t really count as agriculture, but what about pulling up the non-wheat interlopers from a half-ripe stand you hope to harvest later in the year? What about saving some seeds and tossing them on a welcoming plot of soil next spring? What about digging up or burning other plants to make that welcoming plot? And then it turns out that all the harvesting and processing tools — those sickles, winnowing baskets, grindstones, and even purpose-built granaries — seem to have existed before there was any intentional cultivation, suggesting wandering tribes who came together only at harvest time but spent most of the year apart. Also, it seems all like those exciting morphological changes that make grain agriculture so efficient (big seeds and non-brittle rachis) come hundreds and hundreds of years after agriculture was established.1 Our simple story is already getting complicated! But it gets worse.

Archaeologists used to assume that sedentism — that is, people staying in one place year-round — and agriculture necessarily went together. In one direction this is obvious, because once you’re feeding your family from a particular plot of ground you probably want to stick around to weed and water it and keep away any animals (or other people) who might swoop in at the last minute and take your harvest. But it goes the other way, too: we generally assume that pickings as a hunter-gatherer are slim enough that your group needs to keep moving around to find more food. (Or, in the immortal words of the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium: “if you continue to hunt in this area, game will become scarce.”) This is actually true at higher trophic levels: large animals tend to migrate throughout the year, so people whose subsistence strategies depend heavily on hunting them will follow the herds. But hunter-gatherer mobility is a tendency, not an iron law, and the archaeological (and even historical) record is full of non-agricultural peoples who lived in one place year-round because their environment was rich enough to support it. This was common among the tribes of the Pacific Northwest, who created quite socially and materially complex cultures without agriculture, but it also shows up plenty of other places. The earliest sedentary culture we know about, the Natufians, flourished along the coast of what is now Israel more than thirteen thousand years ago, largely by gathering wild grains and hunting gazelles.

Do note, though, that it would be a mistake to call these non-agricultural environments “natural,” because humans have been actively managing our landscapes for at least a million years. The main tool before the widespread adoption of agriculture was fire, which can be used to stampede prey animals into a trap or to remove unwanted vegetation and make way for the grasses and shrubs that we, or our preferred prey, like to eat. “The game they subsequently bagged,” Scott writes, “represented a kind of harvesting of prey animals they had deliberately assembled by carefully creating a habitat they would find enticing.” It’s even been suggested that the Little Ice Age of the early modern period was due to the sudden cessation of burning activity (and its CO2 emissions) in the Americas when newly-introduced Old World pathogens killed off most of the people who did the burning.

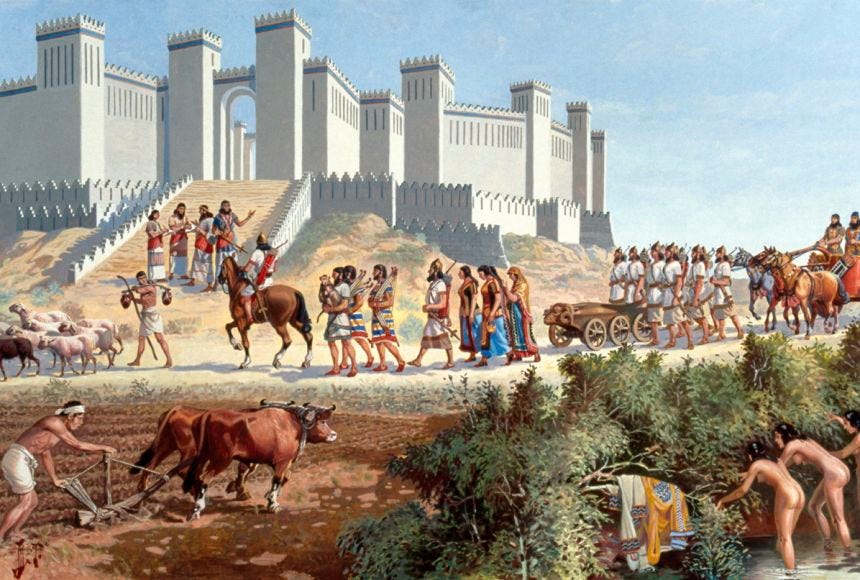

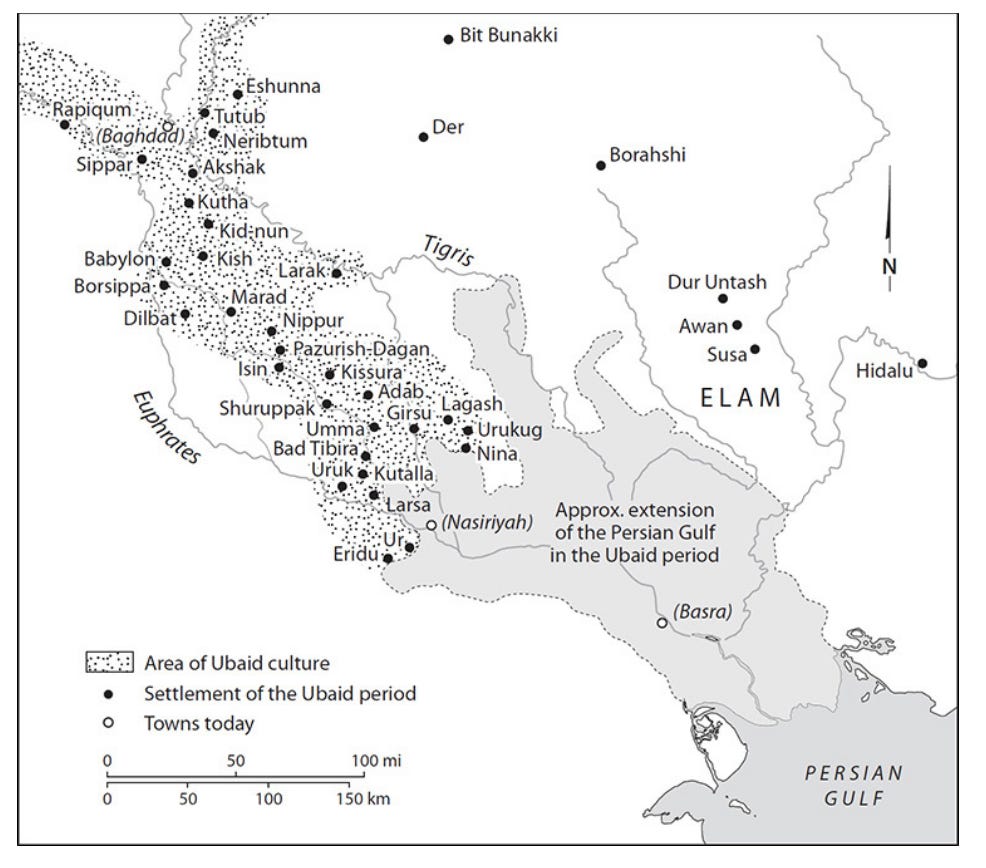

Against the Grain focuses on the region archaeologists call Southwest Asia, people who like reading books about archaeology call the Fertile Crescent, and everyone else calls the Near and Middle East, but it zeroes in specifically on southern Mesopotamia. This wasn’t the first place to host year-round settlements, nor was it the site of the original crop domestications, but it is the home of the third element of the traditional story of the birth of civilization: the state. Scott is unwilling to define the state precisely, describing it instead as an “institutional continuum” where something can be more or less state-like, but he writes that “a polity with a king, specialized administrative staff, social hierarchy, a monumental center, city walls, and tax collections and distribution is certainly a ‘state’ in the strong sense of the term.” It was here, near the mouth of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf, that the earliest “statelets” arose, and it’s here, once again, that Scott brings up recent archaeological evidence that undermines the usual narrative. This time, the abandoned theory is that the region was as arid at the dawn of agriculture as it is today; an agricultural population might have succeeded in the oases and river valleys, but as numbers swelled they would need to undertake massive irrigation projects, which would in turn require “the mobilization of labor to dig and maintain the canals, which implied the existence of a public authority capable of assembling and disciplining that labor force.” In short, agriculture was assumed to have required a state. But it didn’t.

Scott’s argument draws heavily on the work of Jennifer Pournelle, who reconstructed the landscape of the southern Mesopotamian alluvium in the seventh and sixth centuries BC using a combination of remote sensing, ancient sediments, and climatological history, and concluded that, far from the arid landscape of today, the land between the rivers was in fact an “intricate deltaic wetland.”

The inhabitants of these marshes lived on what are called “turtlebacks,” small patches of slightly higher ground, comparable to cheniers in the Mississippi delta, often no more than a meter or so above the high-water mark. From these turtlebacks, inhabitants exploited virtually all the wetland resources within reach: reeds and sedges for building and food, a great variety of edible plants (club rush, cattails, water lily, bulrush), tortoises, fish, mollusks, crustaceans, birds, waterfowl, small mammals, and migrating gazelles that provided a major source of protein. The combination of rich alluvial soils with an estuary of two great rivers teeming with nutrients, dead and alive, made for an exceptionally rich riparian life that in turn attracted huge number of fish, turtles, birds, and mammals — not to mention humans! — preying on creatures lower on the food chain.

Moreover, the first settlements in the area were right on the border between the brackish water of the coastal estuary and the freshwater ecology upstream, and on the incredibly flat floodplain of the lower Euphrates (the gradient is less than two inches per mile) that seam moved great distances with the tides. “Thus,” Scott writes, “for a large number of communities, the two ecological zones moved across the landscape while they remained stationary, taking sustenance from both.” They didn’t need to roam in search of new food sources; the food came to them. Agriculture — of the flood-retreat form, where seeds are sown in nutrient-rich new soils deposited by the retreating river, and which is the least labor-intensive type possible — was just another of their many diverse and overlapping subsistence strategies. The shift between wet and dry season, with its pulse of migrating animals and harvest of whatever seeds they had sown, can be considered moving zones on a longer timescale: a new habitat arriving on their doorstep to be added to the mosaic of available options. By 6000 BC, Scott says, they were “already agriculturalists and pastoralists as well as hunter-gatherers. It’s just that so long as there were abundant stands of wild foods they could gather and annual migrations of waterfowl and gazelles they could hunt, there was no earthly reason they would risk relying mainly, let along exclusively, on labor-intensive farming and livestock rearing.”

Thus do we, with James C. Scott, reject the old model in which agriculture leads almost at once to both sedentism and the state. Instead, we see sedentism arise in particularly favorable ecological niches as early as 12,000 BC, with most of the main founder crops and animals domesticated between 8000 and 6000 BC, and then a gap of almost four thousand years before the appearance of the state. A naively Whiggish view of history might ask, “What took so long?” But James C. Scott, being James C. Scott (yes, here we’re coming to the “turn it on its head” bit), thinks the more accurate question might be, “What went wrong?”

The last step in our new model, where sedentism precedes agriculture precedes the state (with loooooong gaps between them) is the rise of villages in the Fertile Crescent that were occupied by people who got all (or nearly all) of their calories from the cultivation of fully domesticated grains. There were hundreds of these by 5000 BC, dotted throughout the rich southern alluvium, and Scott spends a fascinating chapter on what he terms “late-Neolithic multispecies resettlement camps.” These villages’ “unique and unprecedented concentration of tilled fields, seed and grain stores, people, and domestic animals” formed a novel ecosystem to which organisms — everything from humans on down to domesticated animals, to commensals like sparrows, mice, and dogs, to microparasites like fleas, mosquitoes and mites — had to adapt. He offers some tantalizing suggestions about human “self-domestication” and its effects on our lifeworlds, which I’ll come back to later, but for now just bear in mind that the Neolithic village was far from an idyllic existence. Tilling fields and grinding grain with stone tools is incredibly difficult work, the close living conditions for humans and animals were a perfect breeding ground for zoonoses, and a dramatically limited diet means the skeletal remains of early agriculturalists are generally several inches shorter than those of neighboring hunter-gatherers. Scott offers the following quotation from a 1984 symposium on the Neolithic Revolution (all parentheticals are his):

[Nutritional] stress…does not seem to have become common and widespread until after the development of high degrees of sedentism, population density, and reliance on agriculture. At this stage… the incidence of physiological stress increases greatly and the average mortality rates increase appreciably. Most of these agricultural populations have high frequencies of porotic hyperostasis [overgrowth of poorly formed bone associated with malnutrition, particularly iron-deficiency related malnutrition] and cribra orbitalia [a localized version of the above condition, in the eye socket], and there is a substantial increase in the number and severity of [tooth] enamel hypoplasis and pathologies associated with infectious disease.

And yet despite all these drawbacks, people whose distant ancestors had enjoyed the wetland mosaic of subsistence strategies were now living in the far more labor-intensive, precarious confines of the Neolithic village, where one blighted crop could spell disaster. And when disaster struck, as it often did, the survivors could melt back into the world of their foraging neighbors, but slow population growth over several millennia meant that those diverse niches were full to the bursting, so as long as more food could be extracted at a greater labor cost, many people had incentive to do so.

And just as this way of life — Scott calls it the “Neolithic agro-complex,” but it’s really just another bundle of social and physical technologies — inadvertently created niches for the weeds that thrive in recently-tilled fields2 and the fleas that live on our commensal vermin, it also created a niche for the state. The Neolithic village’s unprecedented concentration of manpower, arable land, and especially grain made the state possible. Not that the state was necessary, mind you — the southern Mesopotamian alluvium had thousands of years of sedentary agriculturalists living in close proximity to one another before there was anything resembling a state — but Scott writes that there was “no such thing as a state that did not rest on an alluvial, grain-farming population.” This was true in the Fertile Crescent, it was true along the Nile, it was true in the Indus Valley, and it was true in the loess soils of “Yellow” China.3 And Scott argues that it’s all down to grain, because he sees taxation at the core of state-making and grain is uniquely well-suited to being taxed.

Unlike cassava, potatoes, and other tubers, grain is visible: you can’t hide a wheatfield from the taxman. Unlike chickpeas, lentils, and other legumes, grain all ripens at once: you can’t pick some of it early and hide or eat it before the taxman shows up. Moreover, unhusked grain stores particularly well, can be divided almost infinitely for accounting purposes (half a cup of wheat is a stable and reliable store of value, while a quarter of a potato will rot), and has a high enough value per unit volume that it’s economically worthwhile to transport it long distances. All this means that sedentary grain farmers become taxable in a way that hunter-gatherers, nomadic pastoralists, swiddeners, and other “nongrain peoples” are not, because you know exactly where to find them and exactly when they can be expected to have anything worth taking. And then, of course, you’ll want to build some walls to protect your valuable grain-growing subjects from other people taking their grain (and also, perhaps, to keep them from running for the hills), and you’ll want systems of measurement and record-keeping so you know how much you can expect to get from each of them, and pretty soon, hey presto! you have something that looks an awful lot like civilization.

The thing is, though, that Scott doesn’t think this is an improvement. It certainly wasn’t an improvement for the new state’s subjects, who were now forced into backbreaking labor to produce a grain surplus in excess of their own needs (and prevented from leaving their work), and it wasn’t an improvement for the non-state (or, later, other-state) peoples who were constantly being conquered and relocated into the state’s core territory as new domesticated subjects to be worked just like its domesticated animals. In fact, he goes so far as to suggest that our archaeological records of “collapse” — the abandonment and/or destruction of the monumental state center, usually accompanied by the disappearance of elites, literacy, large-scale trade, and specialist craft production — in fact often represent an increase in general human well-being: everyone but the court elite was better off outside the state. “Collapse,” he argues, is simply “the disaggregation of a complex, fragile, and typically oppressive state into smaller, decentralized fragments.” Now, this may well have been true of the southern Mesopotamian alluvium in 3000 BC, where every statelet was surrounded by non-state, non-grain peoples hunting and fishing and planting and herding, but it’s certainly not true of a sufficiently “domesticated” people. Were the oppida Celts, with their riverine trading networks, better off than their heavily urbanized Romano-British descendants? Well, the Romano-Britons had running water and heated floors and nice pottery to eat off of and Falernian wine to drink, but there’s certainly a case to be made that these don’t make up for lost freedoms. But compare them with the notably shorter and notably fewer involuntarily-rusticated inhabitants of sub-Roman Britain a few hundred years later and even if you don’t think running water is worth much (you’re wrong), you have to concede that the population nosedive itself suggests that there is real human suffering involved in the “collapse” of a sufficiently widespread civilization.4

But even this is begging the question. We can argue about the relative well-being of ordinary people in various sorts of political situations, and it’s a legitimately interesting topic, both in what data we should look at — hunter-gatherers really do work dramatically less than agriculturalists5 — and in debating its meaning.6 And Scott’s final chapter, “The Golden Age of the Barbarians,” makes a pretty convincing case that they were materially better off than their state counterparts, especially once the states really got going and the barbarians could trade with or raid them to get the best of both worlds! But however we come down on all these issues, we’re still assuming that the well-being of ordinary people — their freedom from labor and oppression, their physical good health — is the primary measure of a social order. And obviously it ain’t nothing — salus populi suprema lex and so forth — but man does not live by bread a mosaic of non-grain foodstuffs alone. There are a lot of important things that don’t show up in your skeleton! We like civilization not because it produces storehouses full of grain and clay tablets full of tax records, but because it produces art and literature and philosophy and all the other products of our immortal longings. And, sure, this was largely enabled by taxes, corvée labor, conscription, and various forms of slavery, but on the other hand we have the epic of Gilgamesh.7 And obviously you don’t get art without civilization, which is to say the state. Right?

We associate human achievement, striving, and greatness with the archaeological remains that testify to them — things like written works and monumental architecture — because often that’s our only evidence that it ever happened. But sometimes, a little clever digging (literal or figurative) can uncover glories of a barbarian past. The most obvious example, of course, is that of the Iliad and the Odyssey, products of a non-state people’s oral culture in the Greek Dark Ages and only recorded with the reintroduction of writing centuries later. How many other texts would be considered classics of world literature if only they had ever become, you know, actual texts? But let’s go beyond art: if you want to talk world-bestriding greatness more broadly, look no further than the ferociously expansive Proto-Indo-Europeans, whose obsession with “imperishable fame” left their DNA all over Eurasia and their culture and even mythology so deeply embedded in their daughter cultures that it can be convincingly reconstructed today.8 Or the Polynesians, whose expansion is arguably even more impressive given how much harder it is to travel across ocean than steppe. Sure, it’s not the Lion Gate or the Mona Lisa — or even the cuckoo clock — but the remains we do have should remind us of the other cultural achievements that have doubtless been lost like tears in the rain.

“What cultural achievements?” you may ask, eyeing the world’s few remaining hunter-gatherers, and it’s true: we judge barbarians of the past by analogy to barbarians of today.9 But that’s not entirely reasonable; there’s no reason to assume that a lack of cultural elaboration among, say, the highlanders of Papua New Guinea reflects anything about the Lapita culture, let alone about the Middle Stone Age or Neolithic Europe.10 It reminds me of the friend who once explained to me, quite seriously, that he would never work for a startup because they’re all culturally dysfunctional and have stupid products. And, you know, statistically he’s probably right: most startups suck, because if they’re any good at what they do they don’t stay startups for long.11 But we all know that different cultures are different: some groups of people see a horizon and burn with the desire to know what’s beyond it, and others don’t. Well, guess who those horizons are going to end up belonging to?

Of course there’s something nice about things that last: the written works and monumental architecture give succeeding generations something to point to and discuss, a jumping-off point for their own striving. Reading Latin is great, partly because you can read what the Romans had to say but more because you can read the same things that every educated person since the Romans has read. But that’s talking about their utility for us, not anything intrinsic to them; if the Huns or the Mongols or the Turks had come a little farther west and despoiled a little more thoroughly, it wouldn’t have retroactively detracted from the grandeur that was Rome. It would simply have turned it into a dark age because it would have left us blind.

You may have noticed that James C. Scott is not a fan of the state. He tends to describe it as a sort of alien intrusion into the human world, an aggressive meme that’s colonized first our material environment and then our minds, imposing its demands for legibility in order to expropriate innocent peasants:

Peasantries with long experience of on-the-ground statecraft have always understood that the state is a recording, registering, and measuring machine. So when a government surveyor arrives with a plane table, or census takers come with their clipboards and questionnaires to register households, the subjects understand that trouble in the form of conscription, forced labor, land seizures, head taxes, or new taxes on cropland cannot be far behind. They understand implicitly that behind the coercive machinery lie piles of paperwork: lists, documents, tax rolls, population registers, regulations, requisitions, orders—paperwork that is for the most part mystifying and beyond their ken. The firm identification in their minds between paper documents and the source of their oppression has meant that the first act of many peasant rebellions has been to burn down the local records office where these documents are housed. Grasping the fact that the state saw its land and subjects through record keeping, the peasantry implicitly assumed that blinding the state might end their woes. As an ancient Sumerian saying aptly puts it: “You can have a king and you can have a lord, but the man to fear is the tax collector.”

This “state as egregore” language recurs throughout the book. Scott writes that the state “arises by harnessing the late Neolithic grain and manpower module as a basis of control and appropriation.” It “battens itself” on the concentration of grain and manpower to “maximiz[e] the possibilities of appropriation, stratification, and inequality,” and with its birth “thousands of cultivators, artisans, traders, and laborers [are]…repurposed as subjects and…counted, taxed, conscripted, put to work, and subordinated to a new form of control.”12 But it’s vital to remember that this metaphor is just a metaphor: the state isn’t actually an alien brainworm or a memetic infohazard that will hijack your neocortex the moment you set eyes on a triumphal arch and force you to spend the rest of your life making lists of things and renaming roads with numbers;13 it’s just an institution that people have invented, because hierarchy and inequality are inescapable facts of life in a society of any scale and the state is a particularly effective bundle of social technologies to leverage those hierarchies. There’s a reason that, after states had their “pristine” invention at least three separate times, they’ve proliferated across every part of the world that can support them!

But more interesting than “are we better off with the state?” is to ask ourselves, as Ronald Blythe does in Akenfield, what has been lost. Here Scott offers some fascinating musings on the way not merely the state but the entire agriculturalist life-world limits us:

We might…think of hunters and gatherers as having an entire library of almanacs: one for natural stands of cereals, subdivided into wheats, barleys and oats; one for forest nuts and fruits, subdivided into acorns, beechnuts, and various berries; one for fishing, subdivided by shellfish, eels, herring, and shad; and so on. …one might think of hunters and gatherers as attentive to the distinct metronome of a great diversity of natural rhythms. Farmers, especially fixed-field, cereal-grain farmers, are largely confined to a single food web, and their routines are geared to its particular tempo. … It is no exaggeration to say that hunting and foraging are, in terms of complexity, as different from cereal-grain farming as cereal-grain farming is, in turn, removed from repetitive work on a modern assembly line. Each step represents a substantial narrowing of focus and a simplification of tasks.

The Neolithic Revolution, he argues, was like the Industrial Revolution, a great boost to human productivity and social complexity but at the same time a deskilling. The surface area of our contact with the world shrank from hundreds of plants and animals, used in different ways at different times of year, to a mere handful of domesticates whose biological clocks became the measure of our lives. Of course, the modern contact area is smaller still — dimensional lumber purchased from a store in place of felling and milling your own trees, natural gas at the turn of a knob with nary a need to build a fire — and is sometimes reduced all the way to your fingertip on a smooth glass screen. The ease and efficiency are undeniable, and I’m sure a forager or premodern farmer would kill for Home Depot and seamless pizza delivery (I certainly wouldn’t want to give them up). But there has been “a contraction of our species’ attention to and practical knowledge of the natural world” because that knowledge and attention is no longer necessary, and I think that Scott is right to suggest that there is something richer about a more extensive involvement with the world. That said, Scott’s case is somewhat overstated: after all, even hunter-gatherers have specialized craftsmen who engage deeply with particular materials at the expense of other endeavors, and farmers14 have a far more intimate relationship with their animals than a hunter does with his many different kinds of prey. Similarly, farmers may be on one particular bit of land but (especially in a preindustrial context) all that plowing and hedging and draining and spiling, not to mention the gathering of various woodland foodstuffs, can rival forager familiarity when it comes to their bit of landscape. (My new favorite poem is Kipling’s “The Land,” on just this idea.)

Scott closes the book with an elegy for the “late barbarians,” who had the best of both worlds: healthier and longer-lived than farmers, and with greater leisure, they were “not subordinated or domesticated to the hierarchical social order of sedentary agriculture and the state” but were still able to benefit tremendously from lucrative trade with those states. Unfortunately, much of that trade was in weaker non-state peoples whom they captured and sold as agricultural slaves, thereby “reinforc[ing] the state core at the expense of their fellow barbarians,” and much of the rest was in their own martial skills as mercenaries (which of course also served to protect and expand the influence of the state). It’s a salutary reminder for the aspiring modern barbarian: the best place to be is just outside the purview of the state, where you can reap its benefits15 without being under its control. But beware, because in a world of states even those “outside the map” must fill niches created by the state. It’s great to have a cushy work-from-home laptop job that lets you live somewhere nice, with trees and no screaming meth-heads on your subway commute, but more land comes under the plow every year, and your time, too, may come.

For more on this, Scott suggests this 2013 paper.

Oats apparently began as one of them!

It was probably also true in Mesoamerica and the Andes, where maize was the grain in question, but Scott doesn’t get into that.

No, the population drop cannot be explained by all the romanes eunt domus.

That famous “twenty hours a week” number you may have heard is bunk, but it’s really only about forty, and that includes all the housekeeping, food preparation, and so forth that we do outside our forty-hour workweeks.

For example, does a thatched roof in place of ceramic tiles represent #decline, or is it a sensible adaptation to more local economy? Or take pottery, which is Bryan Ward-Perkins’s favorite example in his excellent case that no really, Rome actually did fall: a switch in the archaeological record from high-quality imported ceramics to rough earthenwares made from shoddy local clays is definitely a sign of societal simplification, but it isn’t prima facie obvious that a person who uses the product of an essentially industrial, standardized process is “better off” than someone who makes their own friable, chaff-tempered dishes.

Calvert Watkins argues for a Proto-Indo-European Ur-myth in the charmingly-titled How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics, which really ought to contain more stat blocks than it does.

Or, more often, a hundred years ago, since there are vanishingly few non-state peoples left.

I can’t get over how annoying it is that there’s an entirely different set of terms for periods of human history depending on what continent you’re discussing.

I’m sorry if it’s uncool, but by the time you employ someone with a certification from the Society of Human Resource Managers you’re not really a startup anymore even if your office fridge is full of energy drinks.

And of course Scott argues that the state is a parasite in the most literal way, since the word derives from the Greek παρά “beside” + σῖτος “grain.”

Although this would be a pretty sweet novel, sort of a Tim Powers alt-history: anarcho-primitivist occultists go back in time to ancient Mesopotamia to destroy the me of kingship and render the state metaphysically impossible. Someone write this.

Like Scott, in fact, who keeps sheep on 46 acres of Connecticut. There’s a funny little aside in the book where he complains about people using “sheeplike” in a derogatory sense, given that we’ve spent several millennia selectively breeding sheep to behave that way.

Better yet, wait for the peasants to do the reaping then ride in on your shaggy little ponies and take it all. Uh, metaphorically.

I couldn’t have enjoyed this review more! I am glad to have stumbled across your substack.

Excellent review! I will have to pick up a copy of this over the winter.

I find myself wondering if the best way to think of these sorts of society's isn't state/nonstate, or agrarian/hunter gatherer, but rather by why percentage of their population is engaged in what sorts of roles. Every society does a bit of everything, but agrarian societies are far more focused on farming with only a relatively few people who make their living hunting predominantly, etc. That leaves the state as a sort of growing profession; in early stages almost no one can make a living doing "state things", but over time it becomes more and more possible. The state things people do are in some cases beneficial, and in other cases parasitic. In effect, the size of the state partially measures how many stationary bandits the society can support, because they are a decidedly mixed bag.

It also raises interesting questions when one thinks of the classes of jobs that change over time to become more dominant: hunter gatherers give way to agriculturalists, agriculturalists give way to industrial workers, industrial workers to service/knowledge workers. Government workers grow along side the others without necessarily giving way, but at the same time the knowledge worker (or maybe managerial worker) seems like a sub-type of government worker. Maybe they give way to some other sort? What comes next?