REVIEW: A Field Guide to American Houses, by Virginia Savage McAlester

A Field Guide to American Houses (Revised): The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America's Domestic Architecture, Virginia Savage McAlester (Knopf, 2013).

One January a few years ago, I decided to learn about gardening.

It turns out January is the perfect time to do this, because the ground is frozen and there’s no way you can be expected to actually do anything (except read, which is much easier than pulling weeds). So I spent some glorious afternoons wandering the library stacks and checking out enormous, stroller-destabilizing piles of books.

The library is the best way to enjoy gardening books, which tend to be enormous, beautifully photographed in full color and printed on lovely heavy paper, and therefore incredibly expensive — you can grab anything that looks interesting but abandon it without remorse if it turns out not to be.1 I learned all about theories of garden design, the habits and bloom times of different plants, and the intricacies of rose breeding (I’m a David Austin gal), and compiled long hand-written lists of flowers I like, haphazardly organized by scientific name or shade tolerance or what might look nice with what.

I accumulated all this book knowledge while the trees were stark and jagged against the sky and the ground was bare except where shreds of wet leaves clung. It was a dull, grey, snowless winter, and when the Christmas lights came down the outside world seemed entirely bleak and unappealing. Like always, we looked forward to spring — for the warmth that meant we could walk to the park without ten minutes of chasing down stray mittens, for colors, for the smell of life in the air — but when spring finally rolled around, I found it entirely new.

It’s not as though I hadn’t noticed spring before, of course, but knowing what you’re seeing makes all the difference in appreciating it. What used to be a flowering tree was now a redbud or a dogwood or a cherry. A bush laden with snowy blossoms was a viburnum whose cultivar I might be able to identify from the scent (or lack thereof, since all the prettiest viburnums seem to be scentless). The bizarre red sprouts in my neighbor’s yard grew, greened, and revealed themselves as peonies when their massive buds began to droop — a tomato cage eventually appeared to keep them upright.2 I started walking around town just to look at plants, tracking the seasons’ progress through what was in bloom, noticing that my azaleas were still in bud when my neighbor’s sunnier yard was a riot of pink blossoms or the way the hostas grew up to hide the exhausted foliage of the early bulbs. There was a suddenly part of the world I got that I’d never gotten before.

Virginia Savage McAlester’s marvelous A Field Guide to American Houses does for the residential built environment what it took me stacks and stacks of gardening books to do for plants: explain what you’re seeing and why it is the way it is, so that you can see the world around you in a new way. She wrote in the preface to the original 1984 edition that it is “a practical field manual for identifying and understanding the changing fashions, forms, and components of American houses,” so with book in hand (or possibly waiting for you at home, since the paperback weighs three and a half pounds) you should be able walk down any street in America and identify the style of every house you encounter. Aha, the facade is dominated by prominent front-facing gable with a steeply pitched roof and a round arch over the front door? We don’t even need the decorative half-timbering to tell us it’s a Tudor!3

Most of the book is given over to brief but comprehensive chapters on each of nearly fifty different styles of house, from the stately Georgian to the elaborate Queen Anne to the humble ranch. Lest the options overwhelm you, however, McAlester opens with an illustrated cheat-sheet of architectural features that can help you narrow down a house’s style: if you see an eyebrow dormer, for instance, flip to “Shingle” or “Richardsonian Romanesque” and see what other features you can identify.

But this isn’t the sort of book you’ll want to sit down and read cover to cover, unless you’re particularly interested in architecture, because many — perhaps most — of the styles simply won’t exist wherever you happen to be. Sometimes the variation is chronological (you’re obviously not going to get Victorians in an area that was farmland until 1970), but it’s just as often regional: there’s lots of Spanish Revival in the southwest and Florida, where there are original Spanish Colonial buildings, but practically none in New England. Usually, though, it’s both: Greek Revival was the dominant style of American domestic architecture from about 1830 to 1850, to the point it was called “the National Style,” but is practically unheard-of in areas settled after 1860.

Many of the changes in house style were just a matter of fashion: for example, the transition from Georgian to Federal architecture (about which you can read more here) was mostly about shifting tastes in ornamentation and visual weight, like differences in graphic design between a website from 2003 and one from 2023. Local conditions had their part to play, of course — porches have always been far more popular in the South, for obvious reasons. But technological advances in heating, roofing materials, and construction techniques have also done a great deal to influence the forms and structures of American houses, and here McAlester’s opening hundred pages or so are invaluable.

Take roofing: traditional English cottages are typically thatched, but thatch will only shed water if the roof is pitched very steeply. Accordingly, a thatched building can’t be very deep — if you want to make it bigger you have to make it longer, because making it wider would require an impossibly high roof. The earliest buildings in the New World copied familiar European construction patterns wholesale, but the colonists quickly discovered that thatch didn’t stand up to severe New England winters and switched to covering their roofs with wooden planks or shingles — which, incidentally, will shed water at a lower pitch. And since those same long, cold winters made a larger house seem awfully appealing, and a square is a much more efficient way of enclosing the same area, the colonists quickly worked out a lower-pitched framing technique that could span a full two-room depth. Thus, by 1750, most American houses were closer to square than oblong. As for heating, I’ve discussed elsewhere the ways the switch from burning wood to burning coal changed domestic architecture; McAlester extends it to central furnaces (coal or, later, oil and gas) that could heat a large or irregular house without needing multiple stoves or grates.

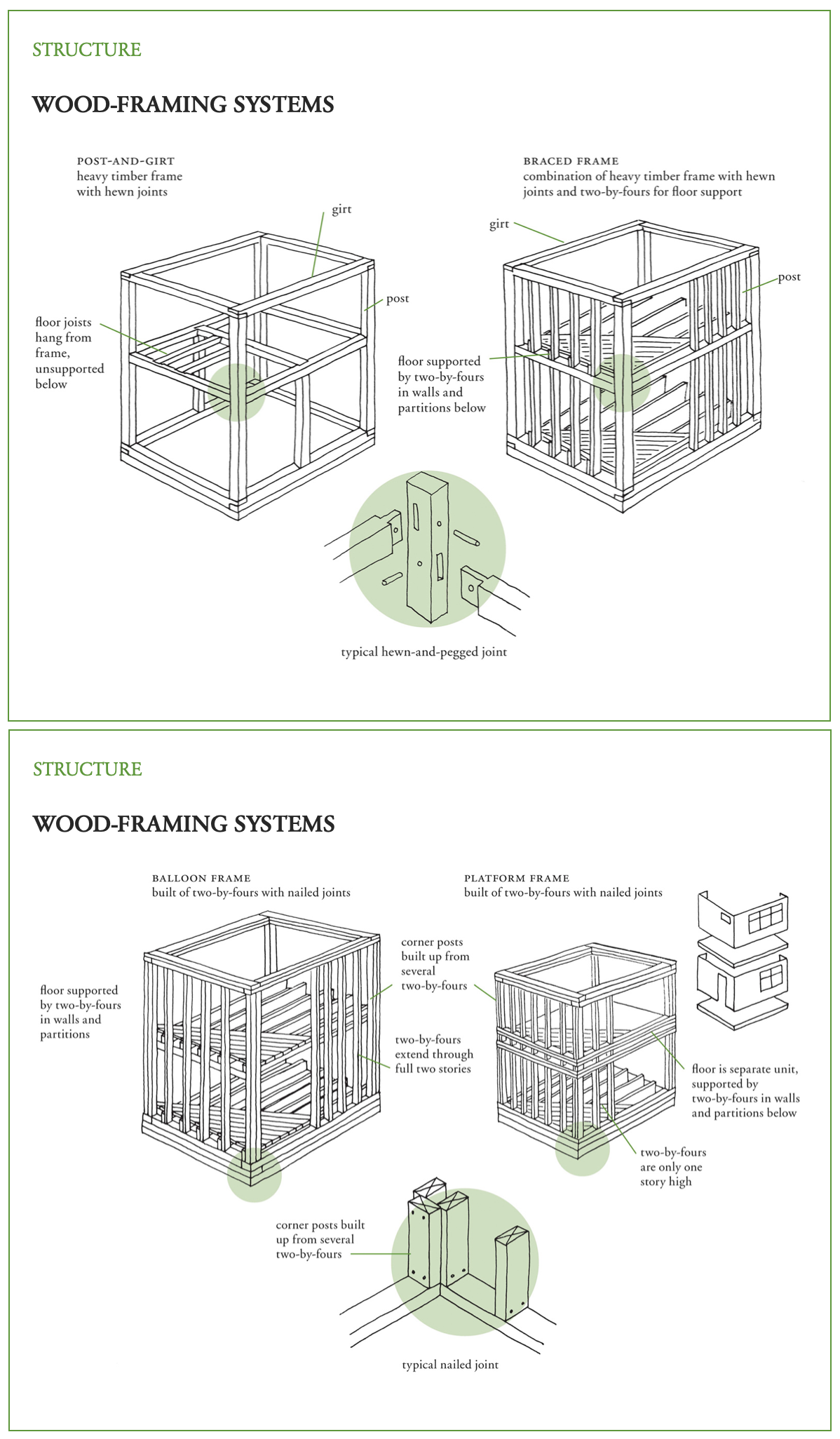

But if we’re trying to identify a house from its exterior alone, the most dramatic technological change comes in the 1830s with the development of balloon-frame construction. This is more or less how most houses are built today — a skeleton of light-weight wood framing made of standardized dimensional lumber — so you’ll recognize it if you live in a part of the country where people are allowed to build things.4 You’re probably less familiar with the construction techniques that came before: solid masonry or heavy timbers. They’re both incredibly labor-intensive (if very sturdy!) ways of building, but when we’re looking at the shapes of houses, the most relevant factor is that they both make it very difficult to build a corner. Stone or brick are prone to erosion at the corners and need specially strengthened patterns to avoid instability, while corners in a timber frame require hand-hewn mortise-and-tenon joints. By contrast, with balloon framing, all you need to make a corner is a few extra boards and some nails.5 Irregularly shaped houses with many exterior corners suddenly became practical, and by the 1850s they were widespread.

If it’s hard to envision what I mean, check out these links and compare the shapes of Georgian mansions like Philadelphia’s Stenton House (built 1734) or Marblehead’s Lee House (built 1768) to the Second Empire Davies House (built 1868) and the early Queen Anne Baldwin House (built 1877). Even Thomas Jefferson’s mansion Monticello (built 1809), which has an unusual number of corners and semi-octagonal shapes for the era (he was very rich and very interested in architecture) is more or less a square compared to a later mansion like Chateau sur Mer (built 1852). (Monticello floor plan; Chateau sur Mer floor plan.)

It’s hard to overstate how dramatically balloon framing changed the shapes of American houses: even a bog-standard, highly symmetrical Colonial Revival like the Home Alone house has some irregularities to its facade that mark its era clearly. The Victorians, Tudors, Craftsman houses, and various eclectic styles are even more highly marked by irregular shapes.

But as dramatically as technological change has shaped our houses, it’s had even more profound effects on the ways our houses are grouped together into neighborhoods. McAlester devotes a long and fascinating chapter to this topic; I’m going to get into it in some detail, but there’s much, much more in the book, and I encourage you to check it out even if you don’t give a hoot about house styles.

After some brief but interesting discussion of cities,6 most of the page count is devoted to the suburbs. It’s a sensible choice: suburbs have by far the most varied types of house groupings, and more than half of Americans live in one. But what exactly is a “suburb”? It’s a wildly imprecise word, referring to anything that is neither truly rural nor the central urban core, and suburbs vary tremendously in character. As a working definition, though, a suburb is marked by free-standing houses on relatively larger lots. (If you can think of a counter-example that qualifies but is “urban,” I’ll bet you $5 it started out as a suburb before the city ate it.)

This means that building a suburb has a few obvious technological prerequisites, which McAlester lists as follows: First, balloon-frame construction, which enabled not just corners but quick and inexpensive construction generally and removed much of the incentive for the shared walls that were so common in the early cityscape. Second, the proliferation of gas and electric utilities in the late nineteenth century meant that the less energy-efficient free-standing homes could still be heated relatively inexpensively. Third, the spread of telephone service after 1880 meant that it was much easier to stay in touch with friends whose front doors weren’t literally ten feet away from yours.7 But by far the most important technological advances came in the field of transportation, which is obviously necessary if you’re going to live in the country (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) and work in the city.

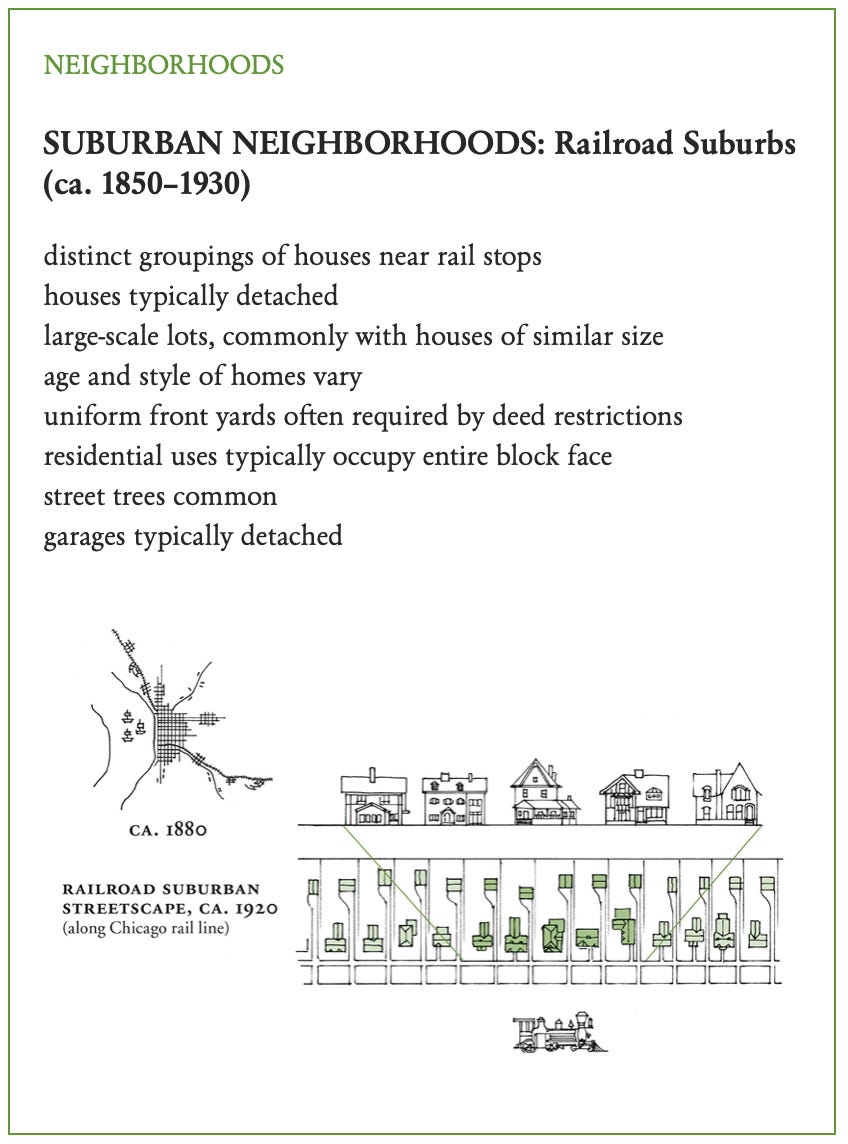

The first of these transportation advances was the railroad. In fact “railroad suburb” is a bit of a misnomer, because most of the collections of houses that grew up around the new rail stops were fully functional towns that had their own agricultural or manufacturing industries. The most famous railroad suburbs, however, were indeed planned as residential communities serving those wealthy enough to pay the steep daily rail fare into the city. Llewellyn Park near New York City, Riverside near Chicago, and the Main Line near Philadelphia are all examples of railroad suburbs that have maintained their tony atmosphere and high property values.

The next and more dramatic change was the advent of the electric trolley or streetcar, first introduced in 1887 but popular until about 1930. (That’s what all the books say, but come on, it’s probably October 1929, right?) Unlike steam locomotives, which take quite a long time to build up speed or to slow down again, and so usually had their stations placed at least a mile apart, streetcars could start and stop far more easily and feature many more, and more densely-placed, stops. Developers typically built a streetcar line from the city veering off into the thinly-inhabited countryside, ending at an attraction like a park or fairground if possible. If they were smart, they’d bought up the land along the streetcar beforehand and could sell it off for houses,8 but either way the new streetcar line added value to the land and the development of the land made the streetcar more valuable.

You can easily spot railroad towns and streetcar suburbs in any real estate app if you filter by the date of construction (for railroad suburbs try before 1910, for streetcar before 1930) and know what shapes to look for. Railroad towns are typically farther out from the urban center and are built in clusters around their stations, which are a few miles from one another. Streetcar suburbs, by contrast, tend to be continuous but narrow, because the appeal of the location dropped off rapidly with distance from the streetcar line. (Lots are narrow for the same reason — to shorten the pedestrian commute.) They expand from the urban center like the spokes of a wheel.

And then came the automobile and, later, the federal government. The car brought a number of changes — paved streets, longer blocks, wider lots (you weren’t walking home, after all, so it was all right if you had to go a little farther) — but nothing like the way the Federal Housing Authority restructured neighborhoods.

The FHA was created by the National Housing Act of 1934 with the broad mandate to “improve nationwide housing standard, provide employment and stimulate industry, improve conditions with respect to mortgage financing, and realize a greater degree of stability in residential construction.” It was a big job, and the FHA set out to accomplish it in a typical New Deal fashion: providing federal insurance for private construction and mortgage loans, but only for houses and neighborhoods that met its approval. This has entered general consciousness as “redlining,” after the color of the lines drawn around uninsurable areas (typically old, urban housing stock),9 but the green, blue, and yellow lines — in order of declining insurability — were just as influential on the fabric of contemporary America.

A slow economy through the 1930s and a prohibition on nonessential construction during the war meant that FHA didn’t have much to do until 1945, but as soon as the GIs began to come home and take advantage of their new mortgage subsidies, there was a massive construction boom. With the FHA insuring both the builders’ construction loans and the homeowners’ mortgages, nearly all the new neighborhoods were built to the FHA’s exacting specifications.

One of the FHA’s major concern was avoiding direct through-traffic in neighborhoods. Many post-World War II developments were built out near the new federally-subsidized highways on the outskirts of the cities, so the FHA was eager to protect new subdivisions from heavy traffic on the interstates and the major arterial roads. Neighborhoods were meant to be near the arterials, but with only a few entrances to the neighborhood and many curved roads and culs-de-sac within it. Unlike the streetcar suburbs or the early automobile suburbs that filled in between the “spokes” of the streetcar lines, where retail had clustered near the streetcar stops, the residents of the post-World War II suburbs found their closest retail establishments outside the neighborhood on the major arterial roads. Lots became wider, blocks longer, and sidewalks less frequent; houses were encouraged to stay small by FHA caps on the size of loans. And although we tend to assume they were purely residential areas, the FHA encouraged the inclusion of schools, churches, parks, libraries, and community centers within the neighborhood.

In 1970, around the time the first ring of post-World War II suburbs finished surrounding the cities, the FHA ceased to oversee most residential construction. The combination of these two facts, McAlester suggests, makes this the date when America entered the era of what she calls “post-suburban sprawl,” especially the “SLUG” (spread-out, low-density, unguided growth) development. The SLUG really is the caricature of the FHA-guided subdivisions: typically tracts of land devoted exclusively to residential use without the parks and community buildings of the postwar neighborhoods and with even the just-outside-the-neighborhood shopping replaced by big-box retail at the intersections of major roads.

The enormous diversity of American suburbs makes any discussion of them peculiarly incoherent: are suburbs soulless mass-produced subdivision of tract housing where you have to drive fifteen minutes just to get out of your neighborhood to the nearest conglomeration of big-box stores? Or are they leafy green idylls where your children can build forts in the backyard and walk to the park with their friends while you grill, garden, or chat with a neighbor? Well…yes, depending. But while there are obvious practical differences between kinds of suburbs — I once asked a friend if her neighborhood was walkable and got an uncertain “well…it has sidewalks?” — they are united by what they have in common: free-standing houses on lots large enough to allow for some attractive landscaping. And, of course, kids.

Suburbs have always appealed primarily to families. In their earliest incarnations, they offered an escape from the danger and disease of the city to those who could afford it; later, they appealed because they gave the joy of homeownership and connecting to the natural world on your own little piece of land. (Also, an escape from the danger of the city; the disease did improve.) The post-war housing boom was concentrated in the suburbs, so the archetypical Baby Boomer childhood — still culturally dominant, like all things Boomer — was suburban. And people really do move to the suburbs when they have kids, because it’s when you have kids it’s nice to have space and your own yard and no shared walls. So I darkly suspect that most of our disagreement about suburbs is actually a disagreement about children and, therefore, about what it means to be human.

To a certain way of thinking, after all, cities are where you get culture, like live theater and fusion cuisine and $20 cocktails; they’re where you get cool parties and bodega cats and the other essential elements of twenty-first century self-actualization. Children interrupt all that: they’re a weird time-consuming hobby, like building model railroads or running ultramarathons, so the suburbs, which are full of children, are a sort of ticky-tacky storeroom for humanity either larval or on hold. Suburbs are where interesting people go once they have kids and cease to be interesting.10

But if you regard children as not just a lifestyle choice but part of becoming a human being, if you believe that creating a home for your family is not drudgery but a valuable undertaking, then you begin to see the point of even an exurban subdivision. (Though I still like sidewalks.)

Just as you can read history in a tree, you can read history in a neighborhood’s streetplans, lot sizes, and layouts. To my mind, though, it’s both easier and more fun to do it from the styles of the houses.

For instance, we used to live in a gently-curvilinear suburb full of Craftsman houses, Colonial Revivals, and the odd Tudor, nearly all built during the height of the local streetcar system in the 1920s but with nods to the rise of the automobile. Head a mile north or south of that old streetcar line, though, and everything is a small brick Minimal Traditional built during or just after World War II. (The familiar Cape Cod-type house is a variety of this type, but not the only one; the Minimal Traditional styles were all officially endorsed the FHA, so builders and homeowners preferred it because it brought guarantees of federal insurance.)

Now we live another five miles farther out from the city in an area that was first settled as its agricultural hinterland. There are a tiny handful of Greek Revivals from before the railroad arrived, but aside from those the oldest houses are all Victorians dating exactly to the arrival of the railroad, mostly Queen Annes but with the odd Gothic Revival in the mix. As the city grew, the railroad began to carry less food and more commuters until sometime in the 1910s, when a streetcar line arrived. As houses filled in what had been fields the farms were cut smaller and smaller (an 1880 Queen Anne up the street sits next door to an 1915 American Foursquare) and the process continued as first the US Highways and then the FHA arrived. My next door neighbors are both Minimal Traditionals built in the late 1950s on what a century before had been the farmland belonging to the whatever Pre-Railroad Folk house was eventually knocked down to build mine.

And of course, because we’re bougie and live in the kind of places that have a Whole Foods, our neighborhoods have always included their fair share of what McAlester very politely does not call McMansions.

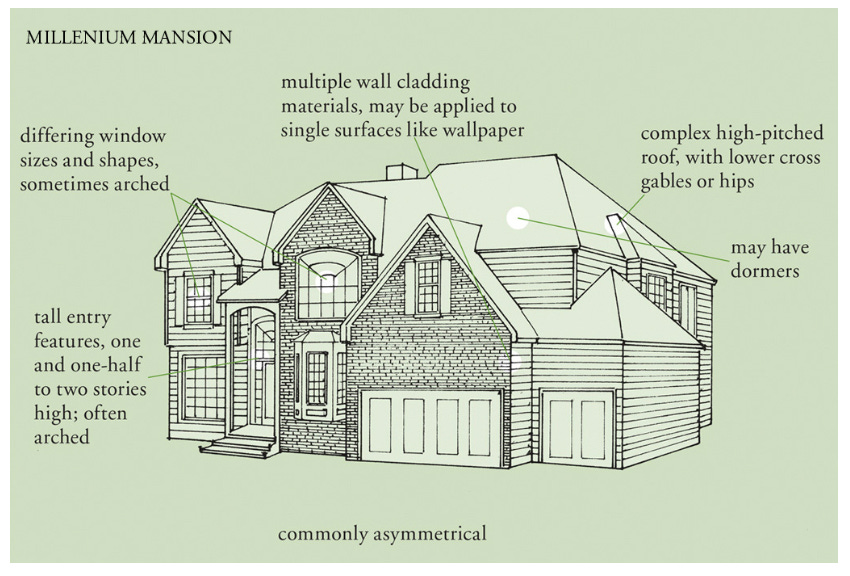

When it come to large and elaborate new construction of the sort that is increasingly replacing little FHA-backed houses in America’s more expensive areas, the field guide offers two possible styles: if the house features a one-and-a-half to two story entry, varied wall-cladding material applied like wallpaper (brick on one wall, stone on another, vinyl siding elsewhere), windows in a variety of shapes and sizes, and/or an unnecessarily complex roof, it may be a Millennium Mansion. If it’s designed to emulate an earlier traditional house style, it’s New Traditional. But unlike the men who built, say, Colonial Revival or Craftsman houses a century ago, modern builders are often unfamiliar with the details of the forms they are imitating, so all but the most carefully-designed New Traditionals are easily differentiated from their models.

McAlester has a long and interesting discussion of the tell-tale details that distinguish a “simplified or poorly-detailed New Traditional” from the real thing,11 but she conflates features that make a house look new (a front-facing garage in the main body of the building is a dead giveaway) with ones that make the house look bad. To be fair, a lot of times these are the same thing: the half-timbering of a Tudor, or the columns of a Greek Revival or Neoclassical house, may not have been functional, but they were carefully modeled in layout and proportions after real structural elements in the Actually Tudor or Classical buildings that inspired them. Contemporary New Traditionals with Classical roots, on the other hand, often make their pillars far too skinny, or with an incorrectly-proportioned (or entirely absent!) entablature, producing an awkward tableau that looks as though it couldn’t possibly be holding up the roof — because it isn’t. And New Traditionals modeled after Craftsman houses, Victorians, Colonial Revivals, and so on are equally prone to unattractive errors in proportion and detail.

But some of the “tells” are simply signs of the times. The front-facing garage is, I’ll admit, not particularly to my taste, but people want somewhere to park and smaller lots limit layout choices; especially when new construction replaces a postwar teardown there’s rarely a rear alley to give alternate automobile access. Charles and Henry Greene, the California brothers who pioneered the Craftsman house, would never have built a two-car garage into any of their intricately detailed buildings, but if they were around now they certainly could without compromising their aesthetics. In fact McAlester includes several photos of attractive examples that do! The modern “McCraftsman” may be ugly, but the culprit isn’t the garage, it’s the poorly-scaled details and skewed proportions — all of which are a matter of careless design rather than necessary features of being built in the twenty-first century.

Then again, our era does seem to be peculiarly marked by careless design. Few of the men who built middle-class versions of the Craftsman bungalow or Colonial Revival in the early twentieth century were trained architects, and they often adapted or simplified their designs to cut costs, and yet they somehow managed to get their proportions right. They might have used fewer columns than the more expensive examples of their styles, but what columns they did employ were the right shape, while today’s are liable to be too skinny (if Classically-inspired) or fat and stubby (if Craftsman). I won’t pretend I have an explanation for this — it seems a small aesthetic piece of a much broader societal failure, just one more case of chucking tradition out the window. Architect Léon Krier suggests that once the language of traditional design had been intentionally destroyed by architecture schools, it was very hard to recreate or rediscover because our new and exciting construction materials do not punish us for our errors the way wood, stone, and lime do. (“Even a genius,” he writes, “cannot build a lasting mistake out of nature’s materials.”)

But the real crime of most new construction isn’t the exterior details. It’s inside, and it’s walls. They’re missing.

Open floorplans are bad. They’re bad for entertaining and they’re bad for families. Sure, that photo looks great (if you’re allergic to color and texture) and the HGTV hosts love ‘em, but imagine actually living in that room with children. Seriously, just try: how fast are the cushions coming off those couches? How fast are your neutrals drowned beneath colorful toys and backpacks? (Unless you’re inflicting the same sad beige color scheme on your children.) How much visual clutter can a room of that size accumulate, and how much help will a small child need just figuring out where to start tidying up?

How many times do you have to ask the monster truck vs. dinosaur battle by the fireplace to pipe down so you can talk to Daddy over here by the stove, for Pete’s sake?

There’s a school of American parenting that says every moment with your child should be spent intensively nurturing his or her precious individual development. At lunch, for instance, you should make eye contact with your ten-month-old and describe the texture and flavor of each food (perhaps in French!) while Baby carefully grinds it into her hair. Your child’s quiet drawing time will surely be enhanced by his mother hovering at his elbow: “Tell me about your picture, honey! Uh-huh, and how do we think the villagers feel about Gigantor devouring them? Gosh, you sure gave him some big teeth!” An open floorplan is a tremendous boon to this sort of parenting: your child is always visible, so you can always be engaged.

It is completely impossible to raise more than maybe two children this way.

I don’t know which way the causation goes — do parents who were already inclined to be a little more laid-back and hands-off find their lives have room for more kids, or does sheer number of children force you to alter your tactics? — but either way, small families and intensive parenting go together, and they live in an open-concept house with 1.64 children.

Walls and doors, on the other hand, are God’s greatest gift to large families. Of course it is wonderful to be together. It’s important to have spaces that will fit everyone. (We were very sad when it was no longer possible to pile everyone into a king-size bed, even with elbows.) But it’s just as important to be able to be apart: because your little brother is practicing piano while you’re trying to do algebra, or a blanket fort combines poorly with an elaborate board game, or just because LEGO spaceships are a noisy business and your mother is reading to your sisters. (Or, God forbid, reading a book herself.)

Because at the end of the day, houses are just the stage where life happens. This isn’t to say that the stage-dressing is irrelevant — there is real worth and value to surrounding ourselves with order and beauty, and understanding how your house or neighborhood got to be that way can illuminate new things about the world. But ultimately, what matters most is how you make it a home.

Learning the Dewey Decimal classifications of the topics that interest you (there are often several, because it’s arranged by discipline rather than subject) is the best way to make serendipity happen. In case you’re wondering: 635 is horticulture and 712 is garden design.

The most beautiful double peonies have enormous, elaborate, dinner-plate-sized blooms — held by stems that are rarely strong enough to keep them up. Unless you’re willing to go to the trouble of staking each stem (and who is, really), you ought to confine yourself to varieties with sturdier stems or smaller blossoms, or to the rarer shrublike tree peonies that are woody enough to stay upright. The only thing sadder than gorgeous flowers flopping on the ground is those same flowers trapped behind chicken wire. Why even bother? I am dedicated to ending the mass incarceration of peonies.

Many of the architectural styles in the book were popular in England too, but because McAlester’s focus is specifically American we can get away without saying “Tudor revival.” (The oldest surviving American house was built c. 1637, well into the reign of the second Stuart monarch, and clearly qualifies as an example of what McAlester terms “Postmedieval English.”)

The modern version, platform framing, avoids the fire hazard of two-story wall cavities, but is otherwise basically the same.

America doesn’t have many urban neighborhoods that predate 1750, and even fewer that persist in their original layout, but if you’ve ever visited one it’s amazing how compact everything feels even in comparison to the rowhouses of the following century.

McAlester’s footnote for the paragraph that contains all this reads: “These three essentials were highlighted in an essay the author has read but has not been successful in locating for this footnote.”

This is still, I am told, how some of the more sensibly-governed parts of the world run their transit systems: whatever company has the right to build subways buys up the land around a planned (but not announced) subway line through shell corporations, builds the subway, then sells or develops the newly-valuable property. Far more efficient as a funding mechanism than fares!

This 2020 NBER working paper points out that redlined areas were 85% white (though they did include many of the black people living in Northern cities) and suggests that race played very little role in where the red lines were drawn; rather, black people were already living in the worst neighborhoods.

There’s also a bizarre phenomenon of upper-middle class parents who pride themselves on their commitment to city life and would never dream of “moving to the suburbs” (doesn’t that mean you have to shop at Walmart?!), but who live in lovely, leafy neighborhoods with big yards and freestanding houses that obviously began their lives as suburbs before the expanding city came to meet them. Austin’s Hyde Park is perhaps the quintessential example of a suburb subsumed entirely into the urban core, but here’s an extremely non-exhaustive list of others which I encourage you to share with anyone who thinks that being within city limits is a sign of moral superiority.

If you want even more, I recommend Marianne Cusato and Ben Pentreath’s Get Your House Right, with foreword by HM The King. Yes, of England. He’s very into traditional architecture. And he has lovely gardens at Highgrove, too, and I very much enjoyed the book about them when I was raiding the stacks.

Thanks for yet another great post! This blog is so consistently fantastic, it is one of my favorite things on the entire internet. I must thank both of you profusely for it.

I'll defend the "children in the city" position, but it needs to be the right city. I live in London (England), and before I had kids I assumed that I, too, would want to move out once I was a parent, but the opposite has been true. I think there has been a relatively recent revolution in child friendliness; public transit is free for kids, nappy changing stations and high chairs are now pretty much universal, museums are basically all well equipped for kids (and free), I live on a big beautiful park with multiple more within walking distance, I get my groceries delivered, school and nursery are sub ten minutes away, the local church hosts (multicultural, five minutes walk) play groups... And there are plenty of other parents around!

Is my house small? Yes, it is, and I admit it would be a squeeze with more than two kids (albeit could renovate the loft to fit a third). But we pack our lunches and are outside almost all of every day, and I don't even own a car; parenthood in the city has been lovely. Looking ahead, London's schools are now excellent and crime is much lower than it used to be.