REVIEW: Invitation to a Banquet, by Fuchsia Dunlop

Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food, Fuchsia Dunlop (W. W. Norton & Company, 2023).

One sunny December morning years ago, Jane and I were on holiday in the South of China. Far from the city, a little temple had been hewn out of a seaside grotto so that it partially flooded when the tide came in. We stood inside and gazed up at a statue of 觀音, “Guan Yin,” the lady to whom the temple was dedicated. Her legend originated in India, where she was known as the bodhisattva Avalokitasvara, but she’d been absorbed and appropriated by Chinese folk religion many centuries ago, and in this statue there was no trace to be found of her South Asian origins. A minute or two into our reverie, a local came over to us and, seeing that we looked out of place, helpfully explained in unaccented English, “This is one of the most important Christian goddesses.”

The Chinese are almost as bad as the Romans were about pilfering the deities of their neighbors, so you really can’t blame them when they occasionally get confused about who they stole them from. As with goddesses, so with food: earlier that day a different helpful local had steered us towards a restaurant specializing in “Western cuisine.” The menu listed steaks “French style,” “German style,” and “Barbecue style.” Soup options included minestrone and borscht, both of them with the surprise addition of prawns. Their pride and joy, however, was their breakfast menu which included roughly seventy different varieties of toast. The chef told me that there were restaurants in Europe and America that did not have so many kinds of toast, and beamed with pride when I nodded gravely. One of the diners, delighted to see real living and breathing Westerners in her local Western restaurant, told me: “The thing I love about this place is that it’s so authentic.”

This “Western” restaurant may sound ridiculous to you, but it’s only as ridiculous as most of the “Chinese” restaurants you’ve encountered in the West. First of all, there’s no such thing as “Chinese” food. China is a country, but it’s the size of a continent, and it boasts a culinary diversity which exceeds that of many actual continents. Second, the dishes you encounter in the average Chinese restaurant over here bear about as much resemblance to real Chinese food as the seventy varieties of toast and the barbecue steaks do to French cuisine. “American Chinese food” is an interesting topic in its own right, and there are some good books about it, but now that I’m through the mandatory throat-clearing you have to do when writing about Chinese cuisine for a Western audience, I’m never going to mention it again.

China is a food-obsessed society. People are always talking about their next meal. People talk about it incessantly. The Chinese equivalent of talking about the weather, a way of making polite chitchat with strangers, is to mention a restaurant that you like, or a meal that you’re looking forward to. A standard way of saying “hello” in Mandarin is “你吃饭了吗?” In Cantonese it’s “你食咗飯未呀?” Both of them literally translate as something like “have you eaten yet?” and produce a natural conversational opening to begin immediately discussing food. Perhaps most uncanny to foreigners, Chinese people will sometimes discuss their next meal while they are in the middle of eating a fancy dinner. Dozens of gorgeous little dishes spread around them, chomping or slurping away at exquisite cuisine, and happily chattering about what they plan to eat tomorrow.

None of this is remotely new. If anything, between the Revolution and the famines, Chinese food culture is actually tamer than it used to be.1 We know this from literary and historical accounts, from archeological evidence (China had fancy restaurants about a thousand years before France did), and from the structure of the language itself. They say the Eskimos have an improbable number of words for snow,2 but the Chinese actually do have a zillion words for obscure cooking techniques. What’s more, many of the words are completely different from region to region, which is hardly surprising since the food itself is bewilderingly different from one side of the country to the other.

How food-obsessed are the Chinese? One of the most priceless artifacts belonging to the imperial family, the one thing the fleeing Nationalists made sure to grab as communist artillery leveled Beijing, now the most highly-valued object in the National Palace Museum in Taipei is… The Meat-Shaped Stone.3 A single piece of jasper carved into a lifelike hunk of luscious pork belly, complete with crispy skin and layers of subcutaneous fat and meat. Feast your eyes upon it.

Between the foreignness and the sheer, overwhelming size of the topic, it might seem impossible to conduct an adequate survey of the history, vocabulary, and vibe of eating, Chinese-style, for Western readers. But that’s why we have Fuchsia Dunlop. She’s an Englishwoman, but she trained as a chef at the Sichuan Higher Institute of Cuisine (the first Westerner ever to do so). She’s written some of the best English-language cookbooks for Chinese food, and now she’s written this book: her attempt to communicate the totality of the subject she loves and which she’s spent her life studying. But the topic is just too damn big to take an encyclopedic or even a systematic approach, and so she wisely doesn’t try. Instead she writes about the weirdest and tastiest and most emblematic meals she’s had, and ties each one back to the main topic. So the book lives up to its name. Like a banquet, it doesn’t try to give you a thorough academic knowledge of anything, but rather a feast for the senses and a feel for what a cuisine is like.

What is it like? Well, Dunlop barely manages to cover this in a 400-page book, so I hesitate even to try, but let me hit a few of the high points. First, diversity. China is a continent masquerading as a country, both in population and in geographic extent, so its cuisine is comparably diverse. Most cooking traditions have one or two basic starches, China has four or five.4 China extends through every imaginable biome, from rainforest to tundra, desert to marshlands, and much of the genius of Chinese food lies in combining the delicious bounties offered up by this kaleidoscope in interesting or unexpected ways.

One way to think of Chinese eating is that much of it is a sort of “internal” fusion cuisine. Because China was ruled from very early on by a centralized bureaucracy with a fanaticism for river transport, the process of culinary remixing has been going on for much longer than it has in most places. The Roman Empire could have been like this, but the shores of the Mediterranean all have pretty similar climates, so there were fewer ingredients to start the process with. Already very early in Chinese history, before the 7th century, we hear of the imperial city being supplied with:

oranges and pomelos from the warm South, […] the summer garlic of southern Shanxi, the deer tongues of northern Gansu, the Venus clams of the Shandong coast, the “sugar crabs” of the Yangtze River, the sea horses of Chaozhou in Guangdong, the white carp marinated in wine lees from northern Anhui, the dried flesh of a “white flower snake” [a kind of pit viper] from southern Hubei, melon pickled in rice mash from southern Shanxi and eastern Hubei, dried ginger from Zhejiang, loquats and cherries from southern Shanxi, persimmons from central Henan, and “thorny limes” from the Yangtze Valley.

If we think of chefs as artists, the Chinese ones have since ancient times had the advantage of an outrageously diverse set of paints. But these ingredients aren’t combined willy-nilly, without respect for their time or place of origin. The Chinese practically invented the concept of terroir, and their organicist conception of the universe in which everything is connected to everything else implied strict rules about which foods were to be eaten when, both for maximum deliciousness and to ensure cosmic harmony.

In the first month of spring, [the emperor] was to eat wheat and mutton; in summer, pulses and fowl; in autumn, hemp seeds and dog meat; in winter, millet and suckling pig. An emperor’s failure to observe the laws of the seasons would not only cause disease, but provoke crop failure and other disasters.

The obsessions with freshness and seasonality come to their culmination in the one area where Chinese cuisine stands head and shoulders above all others: green vegetables. In the West, “eating your greens” is a punishment, or at best a chore, and it’s easy to see why. In much of the world vegetables are bred for yield and transportability, kept in refrigerators for weeks, and then boiled until no trace of flavor remains. Dunlop and I have one thing in common: when we’re not in China, of all the delights of Chinese cooking it’s the green vegetables that we miss the most.

When I bring American friends to a real Chinese restaurant, sometimes they’re shocked that the vegetable dishes cost the same amount as the main courses. Why does a side dish cost so much? But no Chinese person would ever think of a vegetable course as a “side” dish, they’re part of the main attraction, and more often than not they’re the stars of the show. In the West, you can now get decent baak choy, but this is just one of the dozens and dozens of leafy greens that the Chinese regularly consume, many of them practically impossible to find outside Asia.

My own favorite is the sublime choy sum. I remember once getting off a transoceanic flight, starving and exhausted, and being offered a bowl of it over plain white rice. The greens had been scalded for a few seconds with boiling water, then tossed around a pan for no more than a minute — just long enough that the leaves were so tender they seemed to dissolve in your mouth, but the stems still held snap and crunch. The seasoning was subtle — maybe a few cloves of garlic, some salt, a splash of wine or vinegar. Just the right amount to bring out the deep, earthy flavors of the vegetable, to somehow make them brighter and more forward, but not to overpower them.5 It was one of the most delicious things I’ve ever eaten. I think I’ll still remember it when I am old.

Did you notice that in the previous paragraph I spent almost as much time describing the texture of the food as its flavor? That’s no coincidence. Of course the Chinese care about flavor, everybody does (except the British, ha ha), but relative to many other culinary traditions the Chinese put a disproportionate emphasis on the texture of their food as well. I’ll once again draw on a bastardized version of the Whorf hypothesis: English is a big language with a lot of borrowings, so we have a correspondingly large number of words for food textures. Imagine explaining to a foreigner the difference between “crunchy” and “crisp”, or between “soft” and “mushy”. That is already more semiotic resolution than most languages have when it comes to the mouthfeel of their food, but Chinese takes it to a whole ‘nother level.

Dunlop gives the following “non-exhaustive” list of positive texture words (there’s another list of ones with negative valence):

I agree that this is non-exhaustive: I can think of several more. What many of these words have in common is that they’re “multidimensional.” For example consider the Taiwanese slang “Q”, which translates to something like the Italian al dente. Noodles that are “Q” (or even better, “QQ”) have a paradoxical combination of textures: they’re soft and chewy, so your teeth sink into them and your jaw gets a workout, but they’re also elastic and bounce around in your mouth. This is a simple example of a multilayered texture, or you might say of a food with multiple “texture notes”. Chinese chefs delight in combining textures in surprising ways, almost as much as they do flavors. In many dishes, the texture is the whole point, or at least a major one. The Cantonese dim sum snack haa gow — shrimp steamed in translucent wrappers — strikes some people as bland. But a good haa gow is only partly judged on how well it brings out the subtle inner flavors of the shrimp. Most of it is about how the skin combines pertness with falling-apart softness, and how this contrasts with the sometimes unsettling springiness of the shrimp inside. The chef will go to extreme lengths to achieve that interplay of textures with techniques that include salting, starching, shocking with cold or hot water, prolonged refrigeration, and physically beating or smacking the ingredients.

This sensitivity to texture is a big part of why the Chinese eat so much “weird stuff.” Believe it or not, chicken feet don’t actually taste great. In fact, they barely taste like anything, being composed almost entirely of bone, cartilage, skin, and gristle. What they do have is a totally unique mouthfeel, and that’s why they’re in such demand. Similarly, the brains of animals don’t have a very distinctive taste, what they have is an unctuous fattiness and creaminess, difficult to replicate in any other kind of meat. And Chinese people have a great fondness for the tails and the heads of fish — the bits a Western chef usually cuts off and leaves in the kitchen — because they offer an interesting tactile experience. I have a lot of memories of Chinese people hunting for the eyeballs of the fish, popping them into their mouths, and rolling them around with their tongues in a culinary rapture. Which brings me to the fact that this love of odd food textures also implies a different approach to table manners:

You should only eat a giant carp’s tail in the company of someone you know well, because it’s a brazenly messy business, with an unavoidable soundtrack of sucks and slurps. The only actual flesh is a tiny nugget cradled in a curve of cartilage at the distal end of the tail, which you might even tackle with chopsticks. After this easy picking, you must take the tail in your fingers so you can prise apart its two layers of spines, which are interleaved with thin seams of a sticky, ambrosial jelly. This you will want to lick out like nectar, using you teeth to scrape and your tongue to suck along each quill to extract every last delicious thread, leaving nothing but clean spines on the plate.

The Chinese eat a lot of foods that Westerners find disgusting — not just weird parts of animals, but also weird animals: dogs, frogs, monkeys, various bugs, the fetuses of large animals, and so on. There’s an amusing to me assumption that this is somehow the product of famine or desperation, like one year the harvest was bad, and so the family had to eat Fido or Spot with tears in their eyes. This assumption is both patronizing and also an attempt to minimize the cultural differences at work. Westerners can imagine themselves eating this stuff in desperate circumstances, so if that’s why the Chinese started doing it, then we aren’t so different after all. But as Dunlop points out, this story is the exact opposite of the truth. The Chinese have always sought these foods out on purpose, most of it entered the culinary repertoire when times were good, out of the pursuit of ever more obscure and rarefied sensory experiences. They don’t eat these things because they were once starving peasants, they eat them because one time a gang of depraved pleasure-seekers tried them out.6

This is especially true of “Blue China”, the maritime South, which takes adventurous eating to such an extreme that it even horrifies other Chinese people. Dunlop is a bit of a hedonist herself, and also an unabashed partisan of all things Chinese, so there’s an aspect of this she won’t touch and won’t mention in her book. Don’t worry, John Psmith will give it to you straight. The thing about any kind of hedonism is that you eventually run out of exciting new experiences to try, or at least you run out of ones that don’t involve hurting people on purpose. And then it’s just sitting there, the last big taboo, and you’ve already done everything else, crossed every other boundary, could this one be so bad?

That, at least, is my best explanation for the large set of eating practices in the South of China that involve deliberate and performative sadism towards the animal being eaten. The two broad categories are: “torturing the animal before you kill it,” and “eating the animal while it’s still alive.” Texture comes into it too — have you ever heard of the yin-yang fish? It’s where you take a fish and deep-fry just the lower half of its body. That way you can alternate bites of the crispy, crunchy fried parts, and the soft, flaky, still-alive part. And all the while it’s gasping there on your plate, staring up at you with pleading eyes until you eat those too. Perhaps more apocryphal is the practice of eating the brains out of a live monkey. The last semi-credible account I can find of a feast where a monkey’s skull is sawn open and diners eat its brains while it sits in a cage is from 1966, but I bet there’s a club in Guangzhou today where if you pay them enough they can make it happen.

In the case of animal torture, there’s always a pretext for why it’s important, and they usually involve either considerations of flavor or of traditional Chinese medicine. So for instance the dogs that are raised for meat are frequently mistreated, in a way I will not describe, because it ostensibly improves the flavor and consistency of their meat (for all I know this is true, the one time I ate dog it was delicious). Whereas medical and health benefits are the justification for the old Southern Chinese practice of diners goading and stabbing a snake before it’s cooked for them. There are always excuses, just as there are always excuses in any other moral hot-pepper eating contest, but they’re just excuses. The real reasons are “because we can” and “because it’s fun.”

Had enough? I haven’t. There’s one more big taboo, one more line to cross when you’ve tried everything else and are sitting there, bored and jaded. In the Spring and Autumn period, Duke Huan (yes, the same Duke Huan as from the wheelwright story) had a legendary chef named Yi Ya. This Yi Ya was said to have perfect knowledge of every ingredient and how to combine them. One day Duke Huan mentioned offhandedly that he had tried all food on the earth except the flesh of an infant child, at which point Yi Ya promptly cooked and served his own infant son to his master.

You might say “whatever.” After all, almost every culture has myths and legends about cannibalism. For instance in Greek mythology, we have the story of Tantalus killing his son Pelops and serving him to the gods in a stew. The difference is that in most cultures these stories are didactic and meant to inspire revulsion, whereas the moral of the story of Yi Ya is… a little bit more ambiguous. Yi Ya is criticized for lack of loyalty to family (he did kill his son after all), but there are also lots of restaurants and catering businesses named after him. Yes, I’m serious, you read that correctly. The simple truth is that cannibalism is just less taboo in Chinese culture than it is in many others.7 Chinese history, also, is full of episodes featuring mass outbreaks of “gourmet cannibalism” — people eating each other for pleasure, and not because they were starving.

Given all of this, it might be easier to discuss the Chinese culinary tradition in terms of what isn’t eaten. One clue comes from the cycles of assimilation and tension between settled, agrarian Sinitic people and nomadic Southeast Asian hill peoples as chronicled by James C. Scott. In ancient Chinese ethnography, the language used to describe the mostly Sinicized barbarians was “cooked”, whereas their wilder cousins were “raw.” Sure enough, Chinese people don’t eat a ton of raw foods. There are exceptions (including some I’ve already mentioned), but by and large eating ingredients in their natural state, untransformed by fire and by human craft, was considered a “barbarian” thing. Dunlop claims that the Chinese actually invented sashimi, and brought the practice of eating raw fish to Japan, but later gave it up to differentiate themselves from their neighbors.

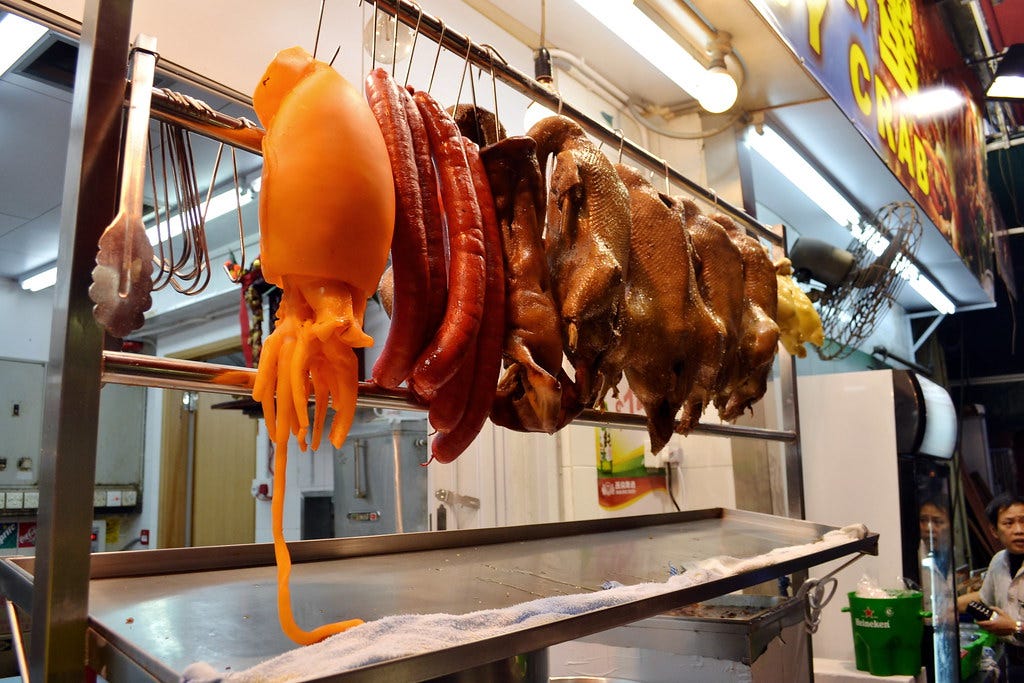

Similarly, the Chinese don’t consume a ton of dairy (though again there are exceptions), and they don’t eat a lot of big hunks of meat that have been simply boiled or roasted over an open flame; because both these behaviors are associated with the other troublesome neighbors — Eurasian steppe nomads. Or at least, they didn’t used to. Dishes like Peking Duck, or like “燒味” (“siu mei”) the delicious cuts of roast pork, goose, duck (and more rarely cuttlefish, chicken, or sausage) that hang in the windows of specialist butchers, are relatively common these days. But they’re a borrowing, like Guan Yin, or like the seventy varieties of toast, relics of the most recent time that the barbarians ruled China.

When the Manchu conquered the crumbling Ming dynasty in the 17th century, they brought their own culinary traditions with them. Since they were pastoralists, those traditions were a little simpler and rougher than those of the effete agriculturalists they ruled over. Manchu officials on assignment would carry personal cutlery sets that included knives for hacking meat off of a large roast, much the way a European would carve a chicken or cut up a steak. This horrified their Chinese subjects, for whom civilization consisted of using chopsticks to eat ingredients that had already been chopped up in the kitchen, and then transformed with complex sauces and cooking methods.

An uneasy peace was achieved only when the great Qianlong Emperor organized the “Manchu-Han Imperial Feast” wherein both cultures were invited to show off their very best culinary techniques over the course of over 300 dishes. Everybody expected the Chinese to steal the show with dishes such as “camel's hump, bear's paws, monkey's brains, ape's lips, leopard fetuses, rhinoceros tails, and deer tendons”; but the Manchu made a strong showing in their section entitled “Platters of Fur and Blood”, with items like charred suckling pig, spit-roasted lamb, roast duck, and other crowd-pleasers.

The Manchu are now nearly gone. Most of them vanished through the age-old Chinese trick of absorbing her conquerors and Sincizing them, and the ones who weren’t Sinicized mostly got massacred in the revolution. Their cuisine lives on, but transformed into something more palatable to Chinese tastes. And this, perhaps, is the most interesting point that Dunlop makes. It would be tempting to blather about how all cuisine is fusion cuisine and actually all of culture was invented by indigenous refugees, or whatever it is that the BBC is currently smoking. But the truth is the Chinese have long held to an extreme sort of culinary nationalism and chauvinism, it’s just no match for a tendency to eat everything in sight.

Ferran Adrià, the legendary chef of El Bulli, once said that Mao was the most consequential figure in the history of cooking because: “[Spain, France, Italy and California] are only competing for the top spot because Mao destroyed the pre-eminence of Chinese cooking by sending China’s chefs to work in the fields and factories. If he hadn’t done this, all the other countries and all the other chefs, myself included, would still be chasing the Chinese dragon.”

I once tried searching Google to find out whether Eskimos really have a lot of words for snow. The top results were all places like BuzzFeed and the Atlantic denouncing this as an outmoded racist stereotype… followed by a Wikipedia article patiently explaining that no it’s actually true.

The Meat-Shaped Stone is not some weird aberration. The runner-up most valuable items in the museum are a piece of jadeite carved to look like a cabbage and a very fancy cooking vessel.

One of them, potatoes, has a particularly fraught history. Potatoes started seriously spreading in China right around the time of the mass famines that accompanied the collapse of the Ming dynasty. Accordingly, they got a reputation of being food for poor people. They’ve never really managed to overcome this association, and are generally shunned by the Chinese, especially in high-end cuisine, despite several government campaigns to encourage people to eat them since they’re nutritious and easy to grow in arid conditions.

There’s a pattern in Chinese gastronomy where extremely intense, over-the-top flavors are a bit low-status, and flavors so pure and subtle they verge on bland are what the snooty people go for. This is true across regions (the in-your-face food of Sichuan is less valued than the cuisine of the Cantonese South, or the cooking traditions of Zhejiang in the East), but it’s also true within regions (in Sichuan, the food of Chongqing is much spicier than the food of Chengdu, and correspondingly lower status).

There’s a wonderful poem from Ancient China called The Great Summons, which is all about using the power of culinary hedonism to call a soul back from the realm of the dead. Here’s an excerpt:

Cauldrons seethe to their brims, wafting a fragrance of well-blended flavours; Plump orioles, pigeons and geese, flavoured with broth of jackal's meat. O soul, come back! Indulge your appetite! Fresh turtle, succulent chicken, dressed with the sauce of Chu; Pickled pork, dog cooked in bitter herbs, and ginger-flavored mince, And sour Wu salad of artemisia, not too wet or tasteless... Roast crane next is served, steamed duck and boiled quails, Fried bream, stewed magpies, and green goose, broiled. O soul, come back! Choice things are spread before you.

There’s actually some sketchy but intriguing evidence from social scientists that people of Chinese descent are less likely to have a physiological disgust reaction to the idea of eating human flesh. As always, this raises interesting questions about which of culture and biology came first.

Lu Xun, the great modernist writer, has a story where the protagonist stays up late reading the Chinese classics and begins to hallucinate that every line reads "EAT PEOPLE!"

Would love to have a complete theory of why some societies consider it totally acceptable to torture animals for fun and other societies consider it repulsive. There are obvious Western examples like bear-baiting and dog fighting, also the entire factory farming system, it's presumably not just a weird Chinese thing. I guess we boil lobsters alive as well.