REVIEW: Road Belong Cargo, by Peter Lawrence

Road Belong Cargo: A Study of the Cargo Movement in the Southern Madang District, New Guinea, Peter Lawrence (Manchester University Press, 1964).

When I was twelve years old, my grandfather gave me a copy of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel. This single fact probably goes farther than any other in explaining How I Got This Way: the book blew my mind and kicked off a lifelong fascination with big-picture, multidisciplinary investigations of how the world, well, Got This Way. (Or, if you’re a hereditarian: roughly 25% of my genes come from a guy who thought this was a good book to buy for a twelve-year-old girl.)

You may remember that Guns, Germs, and Steel is framed as a reply to a man named Yali, a “remarkable local politician” whom Diamond encountered while walking on the beach in New Guinea in July of 1972. (Back before Diamond’s second career as a pop-science public intellectual, he was an ornithologist focusing on the birds of northern Melanesia.)1 They chatted for a while about the prospects for New Guinean independence, and local birds, and then Yali asked a question that Diamond spends a couple of paragraphs boiling down to something like, “Why did human development proceed at such different rates on different continents?” (Which is of course what Guns, Germs, and Steel tries to answer.) But that’s not actually the way Yali put it, and his real question — indeed, his whole story, which is fascinating in its own right — suggests a whole ‘nother set of answers

Yali should be better-known.2 He may have been from a backwards backwater, but he’s one of the true Player Characters of history. If we lived in a better world, he would be the subject of a prestige cable drama3 — or maybe a Robert Eggers film, because the values and assumptions of his society are incredibly foreign to a Western audience. And so to really understand and appreciate Yali’s story (and the question he asked an American ornithologist on the beach one day) you need some background about the tribal cultures of the New Guinea coast and their reaction to contact with Europeans. Which is to say, you need to understand cargo cults! Because what Yali actually asked (per Diamond’s recollection twenty-odd years later) was: “Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little cargo of our own?”

“Cargo” is the catchall word for Western material culture in Pidgin English,4 the lingua franca of New Guinea’s many language isolates, and New Guineans were understandably obsessed: before European contact, they were living in the literal Stone Age. It would be an exaggeration to say that they hadn’t made any technological progress since their ancestors settled the island 50,000 years earlier, since they domesticated several local plants (taro, yams, and the cooking banana) and got pigs plus a little admixture from some passing Austronesians about 1500 BC, but they were solidly Neolithic and had been since time immemorial. So of course as soon as they encountered cargo — especially steel tools, tinned meat and dried rice, and cotton cloth — they wanted it desperately. And they almost universally believed they could get it by ritual activity.

The prescribed rituals varied. One set, recorded in secret by an American Lutheran missionary in the late 1930s, involved the locals setting up tables in front of the local cemetery and decorating them with flowers, food, and tobacco. Then they danced wildly until dawn in twitching, trembling fits so uncontrolled that some devotees continued to sway and shake for days or weeks afterward. Those lucky people were believed to have a special connection to the ancestors that would let them receive dream messages about the cargo shipments their tables and dancing would surely bring. A different cult was led by a man who had a long piece of iron he claimed brought him messages from the future. He told his followers that if they set out all their food in cemeteries as offerings to their ancestors, handed all their Western goods and money to him for safekeeping, and renamed Tuesday to Sunday, they could expect a god to send them airplanes full of cargo flown by the spirits of the dead disguised as Japanese servicemen. These spirits would bring them rifles, tanks, and other materiel and help them drive out the white people, and then the god would change the natives’ skin from black to white. Oh, and also there would be storms and earthquakes of unimaginable violence.

Forget everything you think you know about cargo cults. (Especially forget those pictures you may have seen of “decoy” airplanes or satellite dishes made out of straw and wood: one popular airplane photo is from a Japanese straw festival, another is a Soviet wind tunnel model, and the radio telescope is just one advertisement from a British ice cream company.)5 Nowadays we use “cargo cult” as a lazy shorthand for “copying what someone successful seems to be doing without really knowing why and hoping you get the same result,” but that’s not what was happening at all. If the New Guinea natives built airstrips, it wasn’t out of a belief that airstrips attract cargo planes like planting milkweed brings Monarch butterflies — that would be seem silly but basically understandable from our frame of reference. No, it’s much weirder than that. They built airstrips for exactly the same reason anyone else does: because they thought cargo planes were coming. They just thought the planes were coming because of the dancing.

This is a story about epistemology. And also about Jesus sending you a case of Spam in the mail.

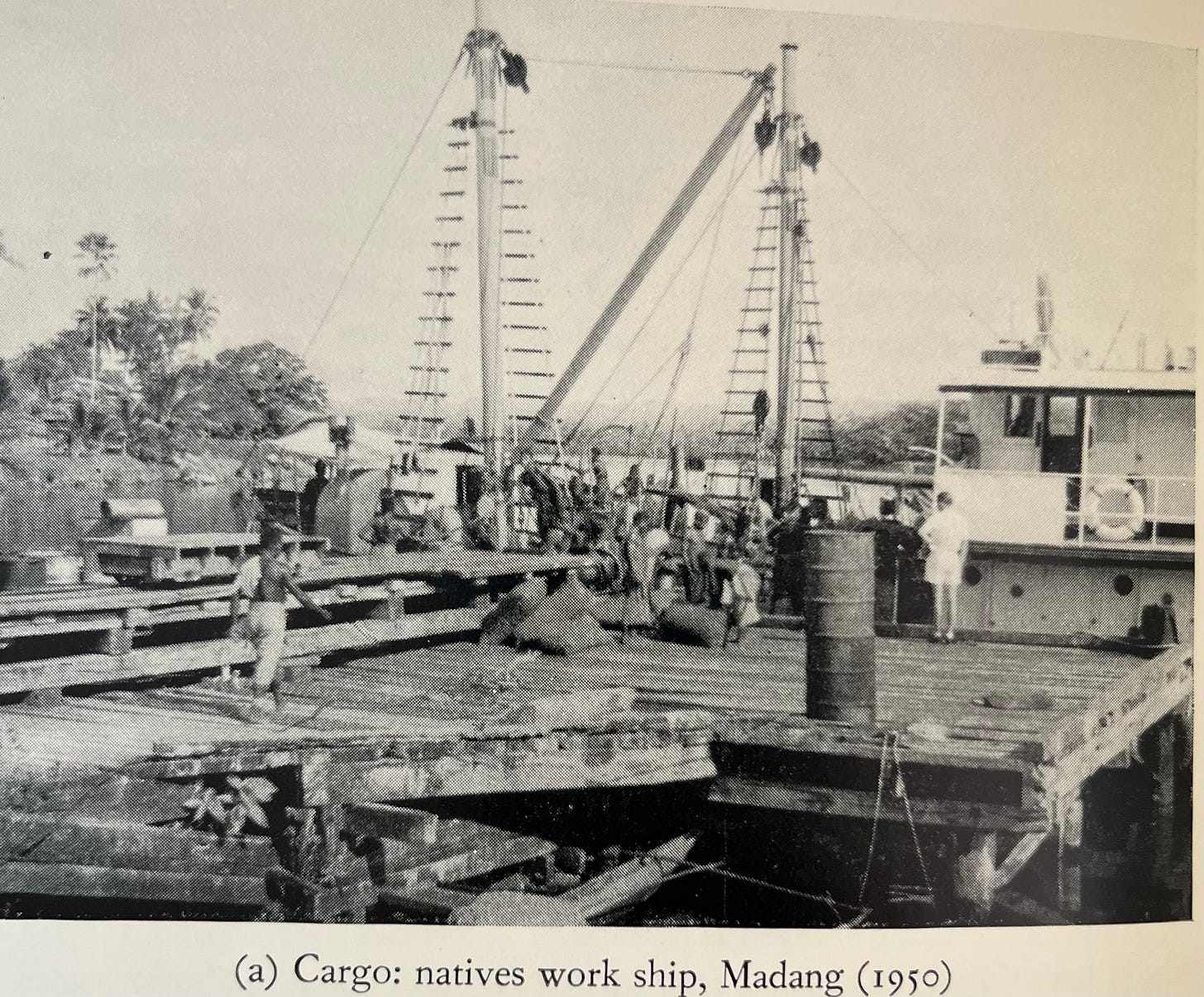

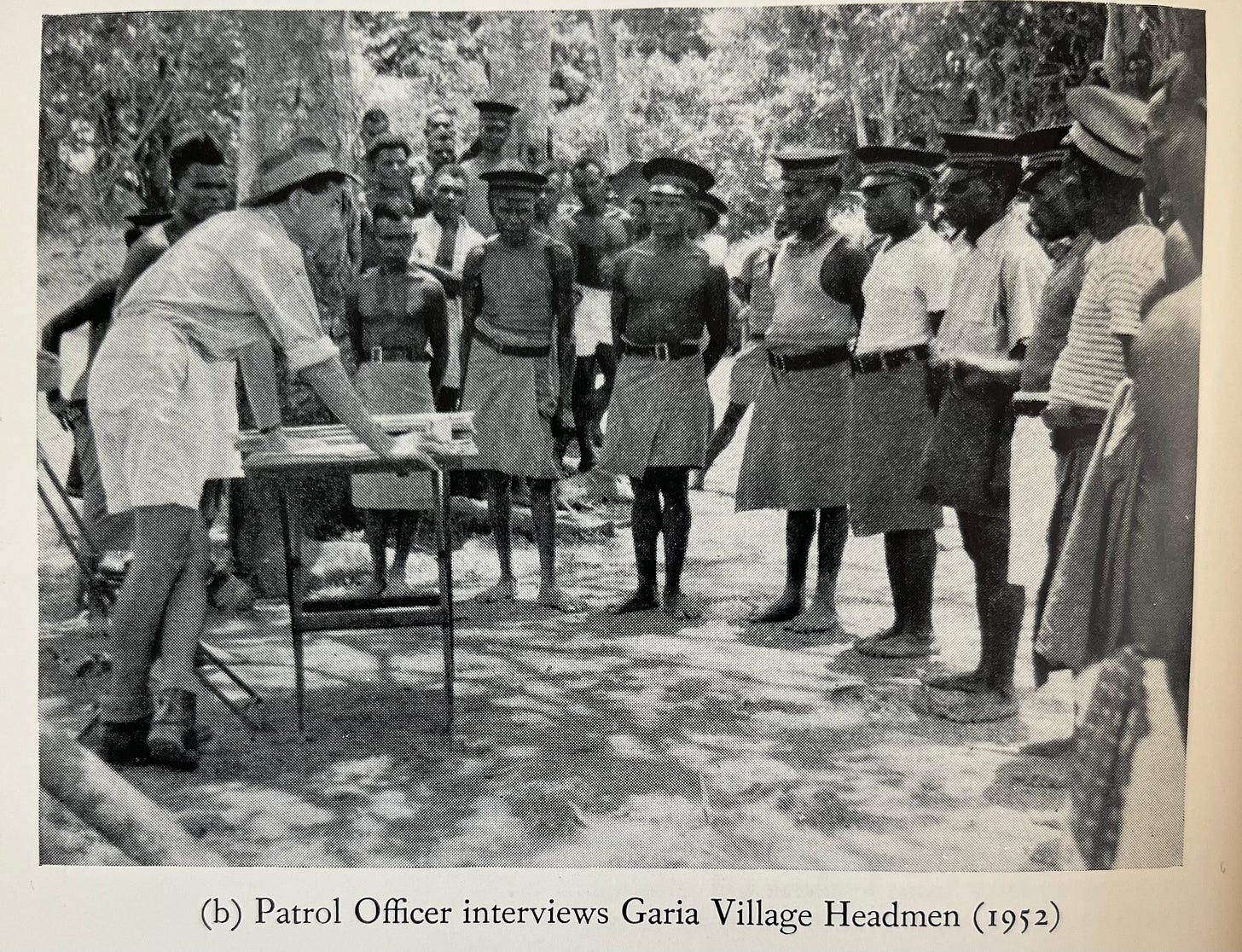

In 1949, Lancashire-born anthropologist Peter Lawrence arrived in Madang Province, New Guinea to do fieldwork for his doctoral dissertation. The Australian colonial authorities then governing New Guinea warned him not to go to the Rai Coast, which was currently rife with unrest due to the periodic cult enthusiasm they called “cargo activity”(not to worry, they added; a local leader called Yali was calming things down). Instead, Lawrence settled some thirty miles west among the Garia, about whom he would eventually write a series of groundbreaking ethnographic studies, and began to do his research. And then, about three months into his stay, his native informants asked him to help organize the clearing of an airstrip. Why? he inquired.

‘To fly in your cargo and ours’, came the embarrassed reply. It eventuated that the expected cargo consisted of tinned meat, bags of rice, steel tools, cotton cloth, tinned tobacco, and a machine for making electric light. It would come from God in Heaven. The people had waited for it for years but did not know the correct procedures for getting it. This was obviously going to change. They now had their own European, who must know the correct techniques and had demonstrated his goodwill. I would ‘open the road of the cargo’ for them by contacting God, who would send their and my ancestors with goods to Sydney. My relatives living there would bring these goods to Madang by ship and I would distribute them to the people. An airstrip would eliminate the labour of carrying.

Lawrence found this all rather surprising: partly because he hadn’t expected to find cargo beliefs so far from the area he’d been told housed cult activity, but also because the Garia explanation seemed perfectly sensible given their assumptions. “I now saw cargo cult as a fascinating intellectual challenge,” he writes. “Previously I had never considered that it had a serious logical basis.” So he began to ask more questions, and he quickly learned that everyone in Madang held some form of cargo beliefs — and that their theories about the source of manufactured goods were a window into their world. Here was far more than the pattern of social relationships he had intended to study (though he would publish on that); it was an entire worldview, complete with “highly systematized ideas about man’s place in a cosmic order.” And once you learned to peer through the New Guineans’ lens, their periodic explosions of cargo cult activity — so threatening and disruptive to the colonial authorities, so damaging to attempts at local economic development — made total sense. So he wrote a book about it.

Madang District (which is in Madang Province) is on the northern coast of New Guinea and is mostly rugged, mountainous jungle that rises abruptly from the coast of the Bismarck Sea. In 1950 Madang had a population of about 24,000, which was fragmented into a then-unknown number of culturally and linguistically distinct groups (some with as few as 150 members). Despite their divisions, though, they traded, intermarried, and went to war with each other, and they all shared a basic cultural outlook and way of life. They lived as subsistence farmers in small villages, growing gardens of taro and banana, keeping pigs, and supplemented their diets with hunting in the bush and fishing in the rivers. They had virtually no social stratification or economic specialization: aside from the few men who were experts in making canoes or conducting religious rituals, everyone did everything from hunting and farming to building houses to making tools, weapons, and clothes.

Lawrence is a trained anthropologist, so of course he spends fifteen pages doing detailed case studies of five different Madang District societies (this one has totems! this one is patrilineal but that one is cognatic!). For our purposes, though, the distinctions don’t really matter: the things you need to understand to make sense of cargo cults — the basic assumptions about material goods and religious ritual — are universal. First, like many small-scale societies, the Madang natives had no real concept of profit, reinvesting surplus, or individual economic advancement. In their subsistence communities, material wealth was as much (or more!) a symbol of social relationships as it was a matter of practical utility. Their entire social world was built around the expectation that you would “think on” (i.e., give your stuff to) a wide network of relatives, neighbors, in-laws, and trading partners, who would then immediately give you back other stuff of equal value. Having stuff was a source of prestige, but only because of what it meant for your connections to other people. In the absence of goods to exchange, there could only be suspicion and the threat of warfare. It’s almost the inverse of our concept of “networking,” where social relationships (while also valued for themselves) are instrumentalized for economic advantage. And it’s self-reinforcing equilibrium: anyone in Madang who managed to accumulate an unusually large amount of stuff, whether through luck or skill, would face a more dramatic version of the “black tax” that plagues people from less-WEIRD societies trying to enter the professional world. There’s no incentive to create wealth when you don’t get to keep it!

The other half of this equation is that New Guineans drew no distinction between the natural and supernatural. They understood gods, spirits, and their ancestors to live in the real physical world, sometimes invisibly and sometimes taking the form of a human or animal. The gods were basically like humans, only more powerful and often possessed of inscrutable whims, and religion was a matter of getting the gods to “think on” you just like a person might. Your relationship with a deity was all about mutual obligation and equivalent exchange: observing taboos and performing rituals created the same kinds of ties between man and god that trading pigs created between man and man. There is no moral or ethical content here; it’s do ut des all the way down. But the New Guineans thought appeasing the gods was absolutely essential, because they believed that all knowledge, technology, and skill — all their agriculture, pig husbandry, seamanship, and clever manipulation of their environment — were not the products of human discovery. Rather, they had been invented by the gods who gave them to mankind. Thus it followed that the ritual knowledge — knowing how to get the gods’ favor — was vastly more important than any kind of practical or technical expertise. If your neighbor has more and healthier pigs than you do, it can’t be that he gives them better food or provides better care; probably he just knows the ritual for a better pig god.

Lawrence sums up these two bits of background like this:

It was these values and epistemological assumptions that provided the threads of consistency in the otherwise variegated socio-cultural pattern of the southern Madang District: the assumption that a true relationship existed only when men demonstrated goodwill by reciprocal co-operation and distribution of wealth; and the unswerving conviction that material wealth originated from and was maintained by deities who, with the ancestors, could be manipulated by ritual to man’s advantage.

And then the Europeans showed up. You can probably see where this is going.

The first white man to set foot in Madang was Baron Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay, a Russian anthropologist who had once been bailed out of jail by Leo Tolstoy.6 Maclay made three trips to the area in 1871-3 and thoroughly impressed the locals, who were fascinated by his enormous ship, his scientific equipment and firearms, and even his clothes. He impressed them even more by his total nonchalance in the face of death: when he was told that two men were plotting his death, he went to their village and told them to kill him quickly because he was tired, then lay down in front of them and went to sleep. And of course he gave the New Guineans gifts of metal tools, mirrors, cloth, beads, paint, and the seeds of unfamiliar plants, so naturally they decided he was a new god who had invented a new type of material culture and was now coming to give it to them. But there was no real attempt to do any kind of ritual — if you wanted Maclay’s goods, all you had to do was come talk to him and offer something in trade.

In 1885, however, New Guinea became a German colony, first through the New Guinea Company and then under direct Imperial rule. (In 1914 it would come under Australian control, which continued in one form or another, except for a brief period of Japanese occupation during World War II, until some time after Jared Diamond met Yali.) The new German settlers were there to make money, not conduct ethnographic research. They were also substantially less friendly to the local inhabitants, who immediately concluded that while Maclay had been one of their own gods who was fond of them, the Germans were hostile gods from elsewhere. Eventually, of course, death rates of Europeans settling in the tropics being what they are, they realized that the Germans were human beings. Still, they were clearly humans whose special god had given them a dramatically superior material culture, and it cried out for an explanation. They settled on something like this:

Here in Madang there lived two brothers.7 One day they fought with each other and decided to go their separate ways. The first brother, Kilibob, built a canoe to paddle away, but the other brother, Manup, built an enormous steel-hulled ship. Kilibob fled in shame at his own inadequacy and Manup began to stock his vessel. He filled its capacious hold with natives and all their things: bows, canoes, yams, pigs, slit-gongs, and so forth. Then he invented cargo and stowed it belowdecks too before setting sail along the coast. At each village Manup passed, he put a man ashore and offered him the choice of either a bow or a rifle, a European-style dinghy or a native canoe with outriggers. Each man rejected the rifle as a useless hunk of wood and the dinghy as too unstable on choppy seas. Finally Manup departed in disgust and sailed off to a faraway land where he met white men. Manup gave the white men all the cargo the natives had been too stupid to select, and also taught them the correct rituals to get more. But one day Manup will come back, and he will bring cargo for us when he does.

There are no records that the people who passed around this myth practiced any particular rituals meant to speed Manup’s return, but the story offered a satisfying explanation of why the Europeans were so much more powerful. That was especially welcome because, by 1914, repeated attempts at both active and passive resistance had been crushed. The locals decided they had no real choice but to cooperate with the Europeans — which meant, among other things, becoming Christians.

There had been Catholic and Lutheran missions in Madang for years, but until this point no one had expressed much interest. In the 1920s, however, villages began to present themselves en masse for baptism. There were a few reasons for this. Partly it was smart politics to ingratiate themselves with their rulers. Partly Christianity seemed to go along with the organized and Westernized lifestyle being imposed on them. But mostly, they wanted cargo. They were beginning to depend on trade goods like metal tools, canned food, and machine-woven cloth, and they wanted more of it. The Europeans had cargo. The Europeans were Christian. Therefore, obviously, Christianity housed the ritual means by which cargo could be obtained — or, in Pidgin English, it was what would opens the rot bilong cargo, the road along which cargo would come.8 They expected their cargo to turn up exactly like the white people’s did: on a ship from Sydney, the main port serving Madang, labeled with their names. The new story went something like this:

God created Heaven and earth. He made Adam and Eve and gave them cargo: tinned meat, steel tools, rice in bags, tobacco in tins, and matches. When they angered God by having sex, he took away their cargo and threw them out to wander the bush. Their descendants grew more and more wicked until at last God decided to destroy the world with a flood, but he saved Noah and showed him how to build the Ark, a European-style steamer, and gave him the clothes of a European ship’s captain complete with peaked cap. When the Flood subsided, God gave the cargo back to Noah’s family. However, Noah’s son Ham was very stupid and witnessed his father’s nakedness, so God took away his cargo and sent him to New Guinea, where his descendants had to make do without any cargo at all. Eventually God felt sorry for the New Guineans and sent missionaries to teach them his ways so that he could send them cargo once more. If we obey God’s commands, he will order the spirits of the ancestors — who live with him in Heaven, which is not (as you may have been told by some foolish people) in Sydney, Australia, but rather in the sky above Sydney — to carry some of the cargo he has created down the ladder from Heaven to the wharves of Sydney, where it will be labeled with our names and shipped to us in New Guinea.

The first recorded cargo cult in New Guinea was just…Christianity.

You might think the missionaries would have realized something was off, but they mostly stayed at their missions; most of the “fieldwork” was done by poorly-compensated native helpers who mostly believed the cargo doctrines themselves, and were eager to convert as many people as quickly as possible to hasten the arrival of cargo in New Guinea. When the new converts did have an opportunity to talk with more orthodox believers, linguistic barriers became a serious problem: perfectly ordinary Christian phrases were understood in completely different ways. “To root out evil” was translated into Pidgin English as rausim Satan,9 but “Satan” had been reinterpreted to mean the old deities with their traditions of polygyny, sorcery, and so forth, who “blocked the road of cargo” and provided an inferior material culture. All the ritual objects were generally known as “satans.” Lawrence quotes a Garia informant who told him, “The local deities always try to trick us into performing the old rituals again in their honour. But what they gave us was only rubbish—taro, yam, and all that stuff. If we yielded to temptation, God would not send us the real cargo—steel tools, tinned meat, and rice.” But it went far beyond that. Among the Garia, Lawrence writes,

‘God blessed Noah’ (Genesis ix. 1) (Pidgin English: God i bigpela long Noa; Garia: Anut Noale kokai älewoya) came to mean ‘God gave cargo to Noah’ on the grounds that in Melanesian culture the concept of blessing could be given practical expression only by the presentation of wealth. The phrase ‘the Mission wanted to help us’ (Pidgin English: misin i laik halivim/litimapim yumi, Garia: misin tianesigebule eya) came to mean ‘the Mission wanted to give us cargo.’ Such phrases as ‘the period of ignorance’ (Pidgin English: taim bilong tudak; Garia: ägisigigem kolilona) and ‘the understanding of God is with us’ (Pidgin English: tingting bilong God istap; Garia: Anut po nanunanu pulina) were understood as ‘the time before the cargo secret was revealed to us’ and ‘we now have the ear of God (and the means of getting cargo)’ respectively.

By the end of the 1920s, Madang was nominally almost entirely Christian, but Lawrence concludes that “relations between natives and missionaries, although on the whole extremely amicable, were nevertheless based on complete mutual misunderstanding.”

Again, this may seem pretty silly to a contemporary Western reader, but imagine for a moment that hyper-advanced aliens have suddenly appeared in your town. They have technology beyond your wildest dreams, and they’re vaguely scornful of your primitive lifestyle — what do you mean you combust hydrocarbons to generate energy? Wait, your planet is still using photosynthesis?! But when you inquire where their fabulous devices come from and how they work, the aliens explain that, obviously, they perform rituals invoking their ancestors, and then their tribal totems deliver and operate their technology. Maybe they even let you watch, and, yep, there the aliens are, vocalizing with their creepy alien noise-sacs and waving their slimy appendages in particular ways, and their hyper-advanced technology coalesces out of thin air and does exactly what they want it to do.

Are you going to say “gosh, I guess my entire understanding of the nature of the material universe is wrong, apparently magic is real”? Of course not. You’re not stupid. You know how the world works. If something is happening, there must be a rational scientific explanation for it. So you develop some theories. Maybe what you can see and hear isn’t the whole story: maybe their rituals are actually activation codes for an invisible cloud of nanomachinery that assembles on command. Maybe they’re emitting some kind of electromagnetic signal you can’t perceive (will the aliens let you do some full-spectrum analysis while they’re invoking the ancestors?), and if you could copy it you could make this work too. Or maybe the aliens are just lying to you, because they don’t want you to have their cool stuff.

That’s more or less where the people of Madang landed when, predictably, it became clear that despite the baptisms, hymns, and prayers…there was still no cargo. One school of thought held that God was indeed sending their ancestors down the ladder to the Sydney wharves with crates of cargo for them and wicked crewmembers were going through the ship’s hold in transit and replacing their names with those of Europeans, but many more concluded that the missionaries were holding back some vital cargo secret to prevent God from sharing the white man’s bounty with the natives. And so, of course, cults arose claiming to teach this secret.

By this point Madang had become sufficiently Christianized — and the European Christians were so obviously in possession of the cargo secret — that the cult doctrines were all syncretic variations on either Catholic or Lutheran theology. They typically claimed that the great secret was that God or Christ was really some figure from traditional mythology. One story (this one belongs to the dancing cult I mentioned above) went something like this:

After Manup gave cargo to the white men, he regretted abandoning us, his original followers, here in New Guinea, and planned to return and make amends. Thus he caused himself to be reborn as Jesus Christ so that he could come here with the missionaries. But the Jews became angry that Jesus-Manup wanted to share cargo with us, so they conspired with the missionaries to imprison him in Heaven and keep the cargo for themselves. When our rituals succeed in setting Jesus-Manup free, he will bring us the rifles he took away from Ham so that we can have our revenge on the Europeans who are stealing our property at sea.

When Japanese troops landed in Madang in December of 1942, many of the cults welcomed them with open arms in the belief that they had been sent by God to liberate the people. Here’s Lawrence:

As the collaborators literally believed that their hope of a better future lay with their new masters, they did everything they could to please them. They told their followers that if the Japanese were to ‘open the road of the cargo’, which the Europeans had persistently ‘closed’, they must help them conquer all New Guinea. They must help kill or drive out every white man or woman, regardless of nationality or status: Australian, German, American, serviceman, or civilian. As a result, many ugly incidents occurred. Allied airmen and other prisoners (including natives) captured in the bush were bound hand and foot, slung on poles, and carried in to the Japanese. It is said that while they were ceremonially beheaded, the natives held dances in honour of the event.

Of course, that turned out poorly: when the Japanese ran out of food and began to retreat under the Allied advance, they stopped paying for the labor they demanded, robbed gardens, stole livestock, and eventually shot and ate the New Guineans themselves. The leader of one cult, outraged by this behavior, marched into Japanese headquarters to upbraid the commanders: he told them that his rituals had brought them to New Guinea, but now that they had shown themselves to be his people’s enemies he would be transferring his support to the Americans and Australians. So the Japanese shot him too.

But the end of the war was far from the end of cargo activity. By 1945, all of Madang was thoroughly suffused with cargo belief, which was intimately tied up with resentment of the colonial authorities who were keeping the cargo secret from them. The Allied military occupation kept things temporarily in check, but in one area where the occupation ws lighter a local cult leader orchestrated a short-lived military uprising with leftover Japanese grenades. Still, there was no clear leader for these forces to crystallize around.

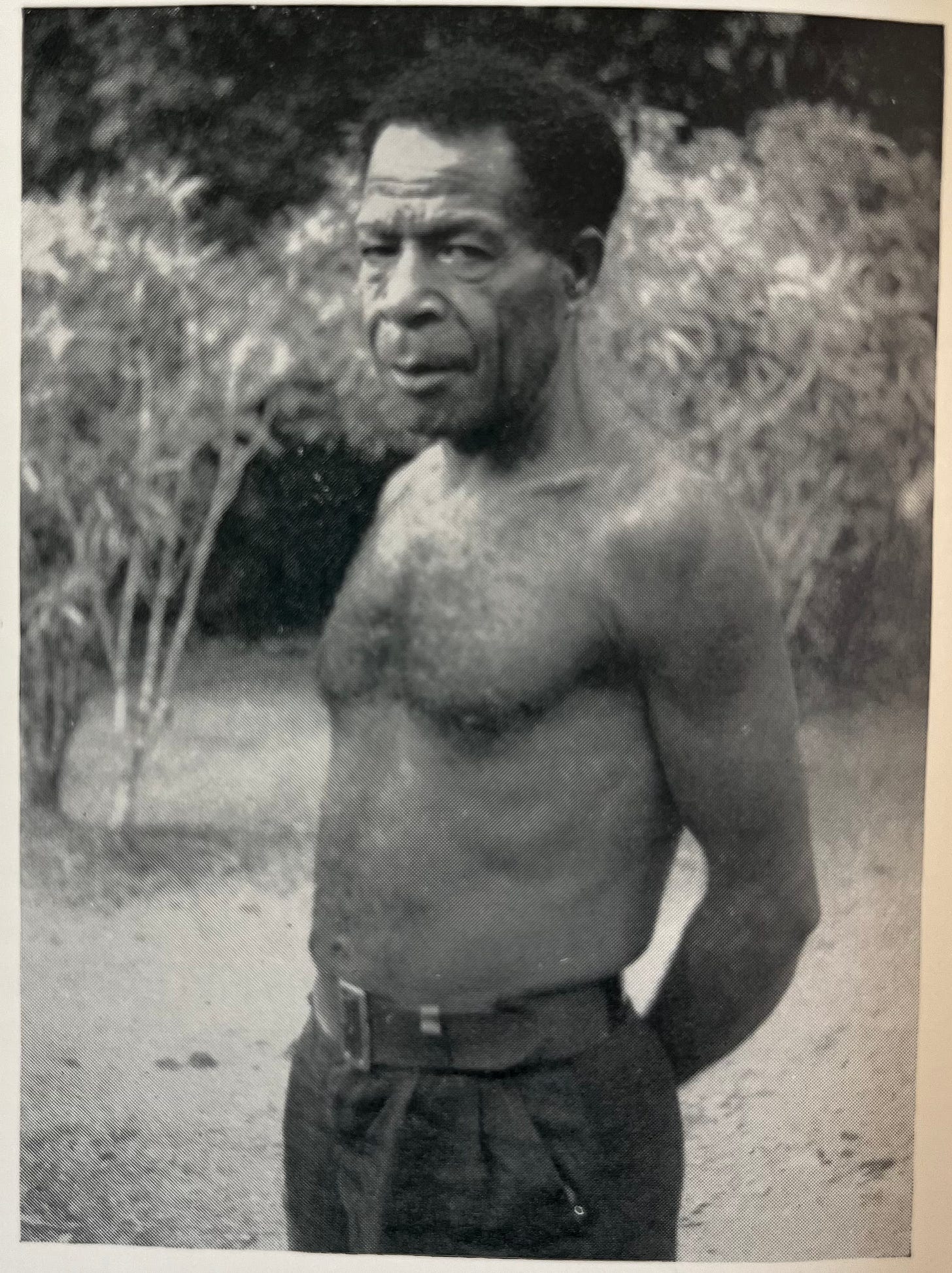

Enter Yali

Yali was an unlikely cargo messiah. Born around 1912 on the Rai Coast (near Madang), he spent his teens and twenties in the liminal places between native and colonial society, first as an indentured servant in a European-style town and then as a local official who assisted the authorities with their patrols into the highlands. After the 1936 death of his beloved wife he joined the Police Force, a paramilitary constabulary staffed by New Guineans and commanded by white Australians. But like many men of his generation, his truly formative experiences came during the Second World War. At a time when many of the New Guineans on the Police Force were deserting or even collaborating with the Japanese, Yali worked closely with his Australian officers in the evacuation of threatened areas and watching the coast for landings. Then in early 1943 he was promoted to Sergeant of Police and sent to Brisbane for special training in jungle warfare. And he was amazed. Here’s the summary from Lawrence, who got it from Yali himself:

Yali saw things which he had never before even imagined: the wide streets lined with great buildings, and crawling with motor vehicles and pedestrians; huge bridges built of steel; endless miles of motor road; and whole stretches of country carrying innumerable livestock or planted with sugar cane and other crops. He was taken on visits to a sugar mill, where he saw the cane processed, and a brewery. He listened to the descriptions of other natives who saw factories where meat and fish were tinned. Again, he suddenly became more aware of those facets of European culture he had already experienced in New Guinea: the emphasis on cleanliness and hygiene; the houses in well-kept gardens neatly ordered along the streets; and the care with which the houses were furnished, and decorated with pictures on the walls and vases of flowers on the tables. In comparison, his own native culture—his rudimentary village with its drab, dirty, and disordered houses, the mean paths in the bush, the few pigs that made a man feel rich and important, and the diminutive patches of taro and yam—seemed ridiculous and contemptible. He was ashamed. But one thing he realized: whatever the ultimate secret of all this wealth—and this he understood in very much the same way as other natives—the Europeans had to work and organize their labour supply to obtain it. Again he compared this with native work habits and organization. He felt humiliated by what he considered the deficiencies of his own society.

And then the Australian Army made him an offer. The exact wording is fuzzy, since this is Lawrence’s translation of Yali’s recollection of what he had been told more than a decade earlier, but Yali reported that he was told: “In the past, you natives have been kept backward. But now, if you help us win the war and get rid of the Japanese from New Guinea, we Europeans will help you. We will help you get houses with galvanized iron roofs, plank walls and floors, electric light, and motor vehicles, boats, good clothes, and good food. Life will be very different for you after the war.” Yali took it literally. If the New Guineans helped the Allies win the war, the colonial authorities would arrive with vast loads of cargo and remake New Guinea along Australian lines. He joined up.

Yali’s wartime exploits were a dramatic tale of adventure and heroism, most notably his epic three-month trek across 120 miles of trackless bush, and he was invited to record a radio talk in which he repeated the promises of Brisbane to his people. After the war, he was praised as a hero and highly regarded by all the military and colonial authorities. He could have been dispatched from Central Casting for the role of “exceptional native” or “Brown Sahib”: tall for a New Guinean, well-spoken and dignified, always dressed in a spotlessly white shirt and immaculately-ironed shorts, he was gallant in action and had been thoroughly loyal in a time when many policemen were openly deserting. Lawrence, who spent weeks talking to him in 1956, writes that he “gave the impression of almost complete Western rationality. He genuinely liked Europeans, took pleasure in their company, and wanted nothing more than to count them among his friends.”

But the assimilation was an illusion. (Or so Lawrence argues — “it was only after several weeks of continuous conversation with him that I realized the truth,” he confesses in a footnote.) Just like the Christian converts who said “blessing” but meant “giving cargo,” Yali could talk with Westerners about public service and civil administration and what he had seen in Brisbane, but he continued to assume that the Westerners’ material culture had been created by their God, who could supplement human production by sending readymade cargo in times of shortage.10 He didn’t expect that anyone would actually hand over the cargo secret, but that didn’t matter — by this point he knew and trusted a great many Americans and Australians, and he was content to have them pass along a share of what God was providing for them.

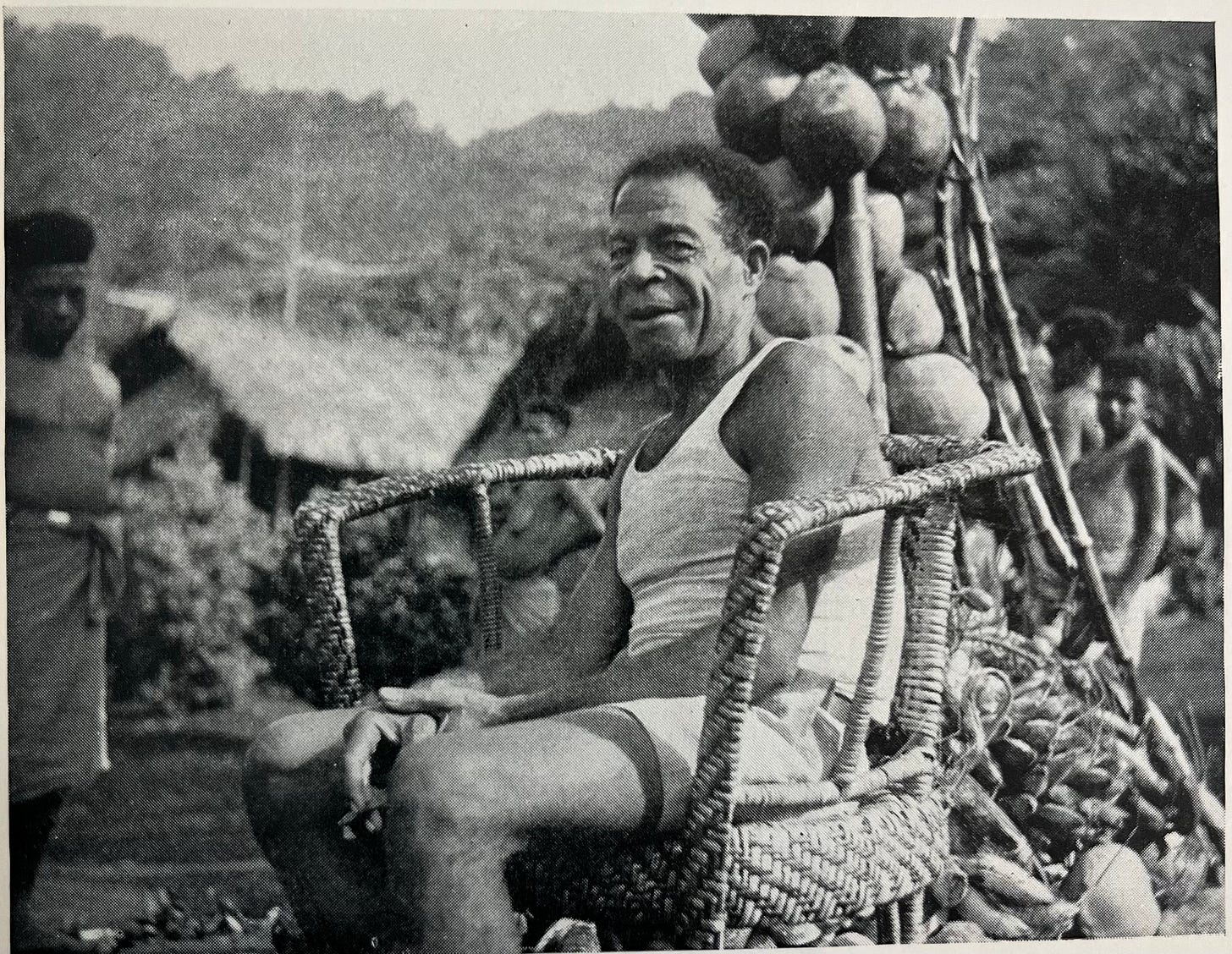

Yali now had a new project: to encourage the people of Madang and the Rai Coast to cooperate with the authorities and get their communities in order so they could enjoy all the goods he had been promised in Brisbane. He set to it with a will, regaling whole villages at a time with the saga of his work against the Japanese occupation, his miraculous trek through the jungle, and what he had seen in Australia. But once again, the message was misinterpreted through the lens of cargo talk: when Yali tried to explain that he had seen fesin bilong wokim kaikai (methods of food production — i.e., factories where food was canned), this was reported as having seen fesin bilong wokim kako (cargo). Soon rumor had it that while he was in Australia, he had seen Jesus-Manup creating cargo — or even more elaborately:

During Yali’s great journey through the bush, he was killed by a Japanese patrol. Like all spirits of the dead, he then went to Sydney, where he met the King. Then he ascended the ladder to Heaven, where he also met God and Jesus-Manup. God promised Yali that after the war, he would send cargo directly to the King, and the King would personally supervise its labeling and lading to ensure that it comes to New Guinea with no interference. Once the cargo arrives, Yali will distribute it to us.

Once again, there were amicable relations based on complete mutual misunderstanding. The people of Madang and neighboring areas thought Yali was a superhuman being who had discovered the secret source of cargo and would share it with them. Yali, in turn, did his best to suppress cargo cults — not because he thought they were wicked or incorrect but because he assumed the Australians would be angry if people tried to steal their property — but kept saying things that cult leaders could spin as endorsing their doctrines. (In fact, they began to invoke Yali in their rituals.) And the authorities in Canberra and Port Moresby saw him as a fully secular, Westernized propagandist who would “prepare the people for the long, slow road to material, social, and spiritual advancement by indoctrinating them with the gospel of hard work.”

It’s not hard to see why they might think so: Yali was encouraging his people to co-operate with the authorities as much as possible and to imitate the Western way of life: to settle in large new villages built in straight lines, with clean well-made houses and streets; to dig latrines and wash themselves and their clothing regularly; to stop their traditional practices of abortion and infanticide so that the population would grow; and to send their children to the mission schools. And people obeyed him with a will: according to a Lutheran missionary, one village copied the only Western lifestyle they had seen, the Allied army camps, and structured their day around whistle-blasts that indicated time for reveille, cleaning, and breakfast. But every time Yali left one area and headed to another, his instructions were inevitably transformed into cargo propaganda. The authorities were beginning to get nervous. So in August of 1947 they summoned him to the capital for guidance.

Yali was delighted. He assumed that he was about to take delivery of all the cargo he had been promised in Brisbane, and he hoped that he would also be given an official position and have his powers and responsibilities clarified. But things went wrong almost immediately: the ship that was meant to take them to Port Moresby broke down and Yali was left to cool his heels for almost a month waiting for spare cargo space on an airplane like an ordinary native. (It was obviously unthinkable to waste a precious passenger seat on a mere New Guinean.) When he finally arrived, he was taken on a variety of official sightseeing tours, instructed on how to organize local village councils of the sort the bureaucrats wanted, and taught about the new program for native education. More encouragingly, he was also appointed local Foreman-Overseer to continue the propaganda and reconstruction work he had already begun, the highest official status any New Guinea native had ever enjoyed. And then he asked about his cargo.

…Yali approached the officer in charge of the party and asked him when the reward pledged to the native soldiers four years earlier would be handed over. When would he and his people receive the building materials and machinery he had been told they were to have? The officer is alleged to have replied that the Administration was, of course, grateful for the services of native troops against the Japanese and was, in fact, going to give the people a substantial reward. The Australian Government was pouring vast sums of money into economic, educational, and political development, War Damage Compensation, and schemes to improve medical services, hygiene, and health. It would be a slow process, of course, but eventually the people would appreciate the results of the Administration’s efforts. But a reward of the nature Yali had imagined—a free hand-out of cargo in bulk—was quite out of the question. The officer was sorry, but this was just wartime propaganda made by irresponsible European officers on the spur of the moment.

Yali was bitterly disappointed. His entire program had been based on the assumption that the promises would be kept and that his people’s standard of living was about to increase dramatically, and now he had to go home and announce that there would be no cargo, only — eventually — some hospitals and maybe some loans to start new businesses. But then something even worse happened: he discovered the theory of evolution.

Yali had long wondered why the various white Native Affairs officers he encountered didn’t seem to care much about Christianity or the missions. Wasn’t that the Westerners’ religion? Now he had an opportunity to discuss the matter with a more educated New Guinean, who explained to him that while some of the white men believed they were descended from Adam and Eve, as the Scriptures said, others believed they were descended from the monki. Yali was furious. Not only had the secular administration reneged on their promises to give him cargo, now it turned out the missionaries had also lied about the origins of mankind. Clearly, they could not be trusted to reveal the cargo secret either. It now appeared that both roads to cargo — indirectly from the Australians and directly from God — were closed. And yet Yali had just been granted official powers and responsibilities, and he still wanted to use them to promote orderly and prosperous lives for his people…who were expecting him to turn up in a ship full of goods he didn’t possess.

If he didn’t want to fall into total disgrace, there was only one solution: Yali leaned into his heretofore-unintentional role as cargo messiah. He went home and told his people that the authorities had reneged on their promises and the missionaries had lied about the road to cargo. Henceforth they must abandon their Christianity (and their quasi-Christian cults, which for them were more or less the same thing) and return to the ways of their ancestors. But this didn’t mean giving up the hopes of cargo: with the help of a new prophet, Yali promulgated a myth that went like this:

As everyone knows, Jesus-Manup, the indigenous New Guinean cargo deity, is held captive in Heaven (above Sydney) as a result of the crucifixion. However, when the missionaries urged us to “root out Satan,” they took many of our satans and put them in glass cases in a place called “Rome.”11 Yali himself saw many of the satans on display in Rome when he visited Queensland in 1943. However, just like Sydney, Rome is connected to Heaven by a ladder, and so one day Jesus-Manup descended the ladder and discovered his fellow New Guinea deities. He immediately taught them the cargo secret, and if we obey Yali’s instructions and return to the old religious ceremonies, the old gods and goddesses will return to us and bring cargo with them.

Through both his formal status from the governing authorities and his role as leader of the new cargo cult, Yali was the single unquestioned authority in the region, free to remake New Guinean life as he saw fit. He instituted his own police, courts, and punishments, and he ran political cover for his cult with the authorities. The people were warned never to repeat their myths lest the Europeans steal the gods back to Australia again; if questioned about the tables they set up and decorated with flowers, for instance, they must simply claim to be beautifying their houses in the Western manner. And so for nearly two years, Yali ruled Madang Province as a virtual king.

His downfall was inevitable — arrest, trial, five years in prison. (In a real Al Capone twist, they got him not on a count of cargo activity but “deprivation of liberty” for the jail sentences he imposed on wrongdoers under his extralegal authority.) By the time he was released the moment was gone; he never recovered his position, though people continued to pay him to “wash away” their baptisms so they could return to paganism. But what about his question? Why is it that the Westerners developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but Yali’s people had so little cargo of their own?

Well, one story goes like this:

Plate tectonics and natural selection created some places that had large seeds, domesticable animals, and few barriers to the spread of people, things, and ideas. The people who lived there were able to have many children and live in great cities, where they could work together to make cargo. Other people were unlucky and lived in places that did not share this bounty, so they had no cargo. The people who had cargo went to the places where people with no cargo lived and were very cruel to them. They told stories about how they were better than the people with no cargo. However, now that cargo has come to the unlucky people who did not have it before, we can see that all people are really the same and that it was only the places they lived made them seem different.

This isn’t wrong in the same way “Heaven is in the sky above Sydney, Australia” is wrong: it probably is pretty hard to develop a state if you don’t have grains, and it would be churlish to criticize the New Guineans for not hitting the Iron Age when there’s virtually zero iron on the island. But it’s missing something vital. For instance, the guy who asked this question was the leader of New Guinea’s greatest cargo cult! That fact seems, I don’t know, relevant. And it’s probably not a complete coincidence that the people who think you get airplanes by doing a dance for the god who invented airplanes didn’t have airplanes. If you think you can’t make new things, of course you won’t.

Jared Diamond is so eager to counter nineteenth-century anthropological theories of racial inferiority that his version of the cargo myth, like all the others, leaves out human agency entirely. But answering Yali’s question doesn’t have to mean choosing between “congenitally stupid” and “passive playthings of geography”: what people do matters, and what people do depends on how they understand the world. Cargo cults were a completely logical, reasonable, and natural extension of the New Guineans’ preexisting beliefs about the origin and function of material culture. Every time they learned something new about Western society and Western goods, they slotted it neatly into their worldview and updated their behavior accordingly. The worldview was just…wrong.

Cargo cults may not be a great metaphor for “copying what someone successful seems to be doing without really knowing why and hoping you get the same result,” but they’re a wonderful metaphor for “assuming the novel thing you’ve just encountered fits a paradigm with which you’re already familiar.” That’s a devilishly difficult trap to escape, and the worst part is that you don’t know you have to: if it were easy to step outside your fundamental epistemological assumptions, they wouldn’t be your fundamental epistemological assumptions. And yet sometimes that’s the only road along which cargo will come.

Okay, fine, it’s actually his third career — he was a specialist in cell membrane biophysics before he started publishing on birds.

Kudos to commenter Gary Mar, who did his part in this project by alerting me to this book in the first place.

Just in case anyone reading this has contacts in showbiz, my other idea for a cable drama is the story of Charles V, Philip II, and William of Orange. The emperor of half the known world, the son and heir raised far away, the beloved ward who betrayed him… It would win twelve Emmys.

Which is not actually a pidgin but a creole! Nowadays it’s more often called Tok Pisin (etymologically, obviously, from “talk pidgin”). Most Tok Pisin vocabulary comes from English, but the grammar and pronunciation are very different and the orthography makes it hard to read. Still, if you try saying it out loud you can sometimes get the gist: “Wetman noken haitim samting moa” pretty easily becomes “white man no can hide’em something more,” and actually means something like “the white man will not keep anything secret from us any longer.”

Credit for tracking down the sources of those images goes to Ken Shirriff in this blog post, which Gwern kindly sent me when I started talking about this book review.

Despite the name, he was not at all Scottish; that’s just his preferred Romanization of Никола́й Никола́евич Миклу́хо-Макла́й.

Their names varied from place to place, but they were always identified with the local culture hero.

Because of its origin as a pidgin, many words in Tok Pisin’s limited vocabulary have a much more extensive meaning than their English roots. Bilong means not just “belonging to” (sista bilong mi, my sister) but also “having a tendency to” (man bilong paitim, an aggressive man; that’s English “fight” plus the +im transitivity suffix) — and, as here, “for the purpose of.”

From German raus! Not all Tok Pisin vocabulary comes from English.

Actually, if you interpret “God” as “the United States of America,” that’s basically what happened during World War II in the Pacific…

Lawrence suggests this is because many of the exhibits in a Catholic mission ethnographic museum in Madang had been sent to the Lateran Museum in 1925 and 1932.

The "black tax" stuff happens in indigenous communities across northern Australia as well. The stories I've heard are like - you make some money by selling paintings, you buy a new fridge, your cousin walks into the house and takes it. You can't stop him because you have deeply baked-in family obligations and your culture has never had enough material wealth to develop a meaningful concept of "theft".

I'm from Brisbane and I know a few people who've done various health or social work type jobs across far north Australia and PNG. Pretty sure we're still just as confused about each other as we were in the days of the missionaries. The question of how to bridge the gap between a basically Palaeolithic culture and fully modern industrial capitalism remains very much alive, and politically tricky, since you're not supposed to say things like "a basically Palaeolithic culture".

One book I like a lot about this topic is Bill Bunbury's "It's Not The Money, It's The Land", about the imposition of minimum wage laws on Aboriginal cattle stockmen in Western Australia. Might only be of interest to Australians but I think it's a great study of how difficult it is to reconcile the Australian system of industrial relations with indigenous concepts of land and property. Two radically different modes of production directly colliding without being able to understand each other at all.

I am speechless after reading this. You make such an important point at the end. I will be thinking of this for a very long time. Thank you so much for writing this review.