JOINT REVIEW: Philosophy Between the Lines, by Arthur M. Melzer

Philosophy Between the Lines: The Lost History of Esoteric Writing, Arthur M. Melzer (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

Jane: Bad news, babe: turns out we’ve been reading philosophy wrong.

The good news is this isn’t an “us” problem: for at least the past two hundred fifty years, literally all of Western civilization has been reading philosophy wrong.

Actually, now that I think about it, that’s worse.1

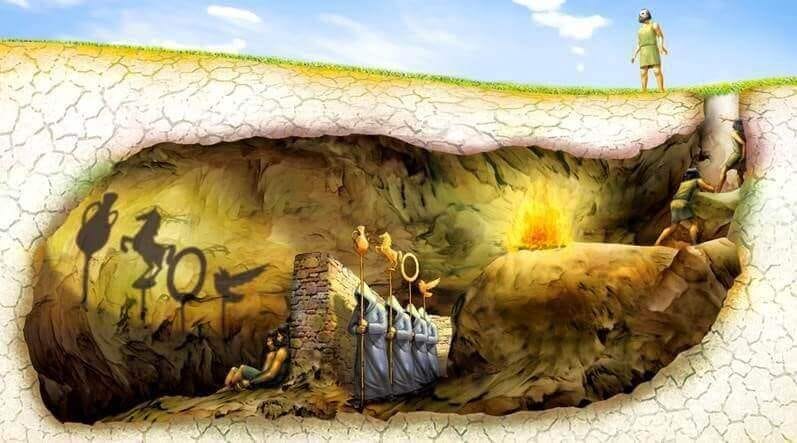

You see, we’ve all been laboring under the delusion that the things philosophers say in their books — right there, on the page, in black and white — represent what the philosophers actually believe. We’ve been taking philosophy at face value. If Aristotle says some men are natural slaves, well, obviously that means Aristotle thinks some men are natural slaves. If Plato says the truly just city requires separating children from their parents, nobly lying about the origins of society, or forcing philosophers to return to the cave, he must think that’s what justice entails. You might disagree! You might even have some arguments to the contrary. But that’s what these great thinkers said, and so, obviously, it must be what they think is true. Why else would a person write something?

But as in so many other cases, this belief marks us out as temporal provincials. Until quite recently, no one expected a philosopher to explicitly state his real teaching where the vulgar, the unprepared, and the (potentially violently) offended could just read it. Everyone accepted that the true message would be hidden “between the lines,” carefully couched in terms the careless or unworthy reader wouldn’t understand, to the point that in the mid-18th century the Encyclopédie would casually explain that “[t]he ancient philosophers had a double doctrine; the one external, public or exoteric; the other internal, secret or esoteric.” Everyone agreed that philosophers in general, and some of the greats in particular, write esoterically: al-Farabi, for instance, wrote that Plato “put in writing his knowledge and wisdom according to an approach that would let them be known only to the deserving,” and Ammonius’s commentary on Aristotle likens the writing of “the Philosopher” to a temple “where curtains are used for the purpose of preventing everyone, and especially the impure, from encountering things they are not worthy of meeting.”

And they didn’t just ascribe this behavior to the past philosophers, they explicitly praised it. Aquinas writes that “[c]ertain things can be explained to the wise in private which we should keep silent about in public. … Therefore, these matters should be concealed with obscure language, so that they will benefit the wise who understand them and be hidden from the uneducated who are unable to grasp them.” Maimonides says that theology should be “hidden from the beginner, and he should be prevented from taking [it] up, just as a small baby is prevented from taking coarse foods and from lifting heavy weights.” Erasmus wrote a letter criticizing Luther for “making everything public and giving even cobblers a share in what is normally handled by scholars as mysteries reserved for the initiated.” And philosophers sometimes even admitted that they themselves wrote esoterically, as when Rousseau described how in his First Discourse, “I have often taken great pains to try to put into a sentence, a line, a word tossed off as if by chance the result of a long sequence of reflections. Often, most of my readers must have found my discourses badly connected and almost entirely rambling, for lack of perceiving the trunk of which I showed them only the branches. But that was enough for those who know how to understand, and I have never wanted to speak to the others.”

That list above is just a taste: Melzer spends twelve pages discussing the evidence for esoteric writing, with a further 110 page PDF on his website. (To compare, he turns up only one piece of evidence against the practice: a footnote from an unpublished essay by a young Adam Smith, who in 1750 mocked the the idea as something “no man in his senses” would ever do.) In short, since the unanimous testimony of the premodern philosophers is that everyone else wrote esoterically, and many of them imply (or even state outright) that they themselves wrote esoterically, I think we have to just accept that they did. Of course accepting that “some philosophy is written esoterically” isn’t the same as saying that any given passage has a hidden meaning, and still less establishing what that hidden meaning is — Melzer gives an esoteric reading of the Republic which is not the same as my own — but it’s an important step in the right direction.

Why do we care? Well, on the most basic level, we want to be right. If we’re going to read a book, we would like to know what it’s actually saying. Misunderstanding the argument because we missed the hidden meaning is just as bad as misunderstanding because we missed the word “not” halfway through the third paragraph. But it goes well beyond that. If we want to understand the history of ideas, we need to know how the philosophers read each other. Of course we ought to figure out what Plato is saying in the Republic, but we also want to know what everyone else thought he was saying. If they all read him esoterically but we accept him at face value, we might as well be reading a different text, and we’ll never be able to see what they were reacting to or against. And there’s an even greater danger to misunderstanding the history of philosophy: it may lead us to misunderstand reason itself.

In previous book reviews (especially here and here) I’ve advanced a sort of universalist, “the law is written on the hearts of men” take: there really is objective moral truth, and it really is to some degree accessible to us through reason. But one of the strongest arguments against that idea is the way writers from very different cultures seem to be deeply constrained by their own context: everywhere we look, Melzer writes, “we see the dispiriting spectacle of the human mind vanquished by the hegemonic ideas of its times.” Ah look, here’s Aristotle, dead white man from a slaveholding society, predictably defending the notion that some people are just meant to be slaves. But as soon as we admit the existence of esoteric writing, the notoriously poorly-argued “natural slavery” passage in the Politics jumps out as a promising spot for further investigation. Maybe Aristotle is doing a bad job on purpose to show you he doesn’t mean it, like the Soviet authors who repeated the party line on dialectical materialism so blandly that it was obviously just window-dressing.

An awareness of esotericism tells us that the appearance of cultural constraint may be mere appearance. “Exactly what you would expect from someone in this setting” is, of course, the only sensible thing to have as your exoteric doctrine: there’s no point in using desert camouflage in the jungle! But if you know camouflage may be involved, you can go looking for it — and when you begin to read esoterically, you will find places where reason has broken out of the assumptions of its time and place and hidden it from the world. Which is all very heartening to those of us who would like to reason about things.

I should probably mention Leo Strauss at this point, partly because he shared my concern about people thinking reason is culture-bound but mostly because it’s his name that everyone thinks of as soon as you say “esoteric writing” (for good reason — he more or less rediscovered the practice.) Melzer is not himself a Straussian, and he doesn’t talk much about Strauss until the very end of the book, but I honestly don’t know how much of Philosophy Between the Lines is warmed-over Strauss because I’ve never read Strauss. I wanted to, back in college, but when I asked an eminent Straussian where I should start he said “Plato’s Republic.”

Okay, so they wrote esoterically. Why? I’ve already hinted at two reasons, which Melzer calls the “defensive” and the “protective”: esoteric writing shields the philosopher from a hostile society, and shields society from the dangers of philosophy. (There are two others, “pedagogical” and “political,” but maybe you’ll cover them later.) But to really make sense of these we need to back up for a minute, because when we talk about a “philosopher” we usually mean someone who does things like writing papers for academic journals about whether knowing how to find coffee in New York City is a fundamentally different kind of cognitive state from knowing where to find coffee in New York City.2 Nobody’s going to make you drink hemlock for that. But in the classical understanding, philosophy isn’t a topic about which you can acquire information, like molecular biology, it’s a fundamental way of life. To become a philosopher is to become a different sort of person through what Plato terms a “turning around of the soul.”

Here’s Melzer:

The philosopher is the person who, through a long dialectical journey, has come to see through the illusory goods for which others live and die. Freed from illusion—and from the distortion of experience that illusion produces—he is able, for the first time, to know himself, to be himself, and to fully experience his deepest longing, which is to comprehend the necessities that structure the universe and human life as part of that universe.

But of course even the philosopher in this proper sense is a political creature, and this isn’t a mere concession to the physical limitations that leave us dependent on our fellow hairless apes. Melzer again:

Political society comes into being for the sake of mere life, according to Aristotle, but exists for the sake of the good life. In the beginning, we create it; after that, it creates us. It turns us from primitive hunter-gatherers into civilized human beings. Rousing us from tribal slumber, it causes the mind to develop and the heart to expand. It transforms us from bodily, economic creatures and clannish family beings into moral beings and citizens. It opens us up to a new world of realities, teaching us to seek honor, love justice, and long for noble and sacred things. The polis constitutes the lifeworld within which civilized humanity can fully unfold. We are deeply political animals, then, because only in and through the political community—this new, moralized, and sanctified world—can we truly become all that we are and experience our full human potential.

Thus intrinsic to our humanity is both the reason that gives us access to truth, and the community that gives us meaning. “We humans are strangely composite beings,” Melzer says, “combining together two different natures—like centaurs or, perhaps, schizophrenics.” Aspects of this doubled nature go by many names — Rorty’s objectivity and solidarity, Heidegger’s reason and existenz, Strauss’s philosopher and the city — but Melzer terms the whole shebang “theory and praxis.” And it’s a problem.

Actually there are several parts of the “problem of theory and praxis,” but it fundamentally boils down to one question: can these two parts of our nature fit together harmoniously, or are they necessarily in conflict? In the beginning, of course, they were both necessary, since reason needs language and social institutions in order to spread and civilization depends for its development on intellect and problem-solving, but once you reach the level of, say, the Greek city-state (just picking examples at random here, guys!), they clash:

When and where reason finally comes fully into its own, when it conceives the radical project of relying entirely on its own powers in making sense of the universe without taking anything on faith or tradition, when, in short, it rises to the level of philosophy, rationalism, or science, then this harmony finally turns to opposition. Reason, nurtured in its initial stages by society, now finds its primary obstacle in the fundamental conventions, traditions, and prejudices of society. Conversely, society, initially provisioned and counseled by reason, now finds a primary danger in philosophy’s relentless drive to question all of the dogmas upon which it is based.

Now remember that we’re not dealing here with the relatively minimalist modern liberal nation-state (yes, in historical context even the hand of Western proceduralist bureaucracy rests remarkably light) but a totalitarian ancient society with no conception of individual rights or even independent individual moral worth. Of course you need to write in a way that won’t make everyone mad at you; I mean, did you see what they did to Socrates? But this is also your city, your patria, your people, who created you and whom you love, and few of your fellow citizens have undergone the “turning around the soul” that would prepare them to handle the harsh truths about the absolute contingency of their moral and religious consensus. And so, of course, you need to write in a way that won’t hurt anyone, either. Esoteric writing is the logical outcome of the conflictual view of theory and praxis.

The Enlightenment counter-move was to reject the conflict entirely: yes, it so happens that theory and praxis were in conflict in ancient and medieval societies, but it doesn’t have to be that way. If we can just bring praxis into line with theory, abandoning prejudice and superstition and constructing our political lives in accordance with reason, we can satisfy both sides of our nature at once! And when that turned into oceans of blood, the Counter-Enlightenment — romanticism and its postmodern heirs — proposed instead to subordinate reason to our “profound political or historical imbeddedness.” All modern thought, Melzer argues, is fundamentally harmonist: now that we believe in progress, we’ve forgotten about tragedy. There couldn’t possibly be an insoluble conflict at the heart of the human experience, so why would you need to write in a way that only makes sense if there is one?

Phew! That was a wall of text, but I think I’ve set the scene for us to discuss all the interesting questions this book raises. Chief in my mind: is the conflictual view right? Even if it is, is it sustainable in a broadly egalitarian polity? How should a contemporary philosopher (in the sense of a way of life, not an academic field) write? Should he even write at all?

John: I think you may understate just how crazy Melzer’s central contention in this book is. He claims (and as you say provides heaps of evidence for his claim) that prior to the Enlightenment it was completely universal knowledge that every philosopher worth reading imbued his texts with hidden meanings. On the contrary, the vast majority of people today (including me until a few years ago) not only do not believe that philosophical texts contain hidden messages, but further do not know that until very recently everybody thought they did. When you really stop and think about it, this pair of facts is jaw-dropping. It’s civilizational forgetting on a nigh-unprecedented scale. As if an entire religion or culture that was once universal has disappeared so totally that we forgot we’d even forgotten it.

This sort of thing is catnip for me, because I’m kind of obsessed with these episodes of global epistemic regress. We know that they happened before — for example calculus was probably invented in the ancient world by Eudoxus of Cnidus and by Archimedes, and then completely forgotten. Or consider that time that the cure to scurvy was discovered and then lost again. The latter example is more interesting, because there was no collapse into barbarism as happened after the end of the Hellenistic world, people just…forgot. Well, if it happened in the past, then I’m sure it’s happening now too, but trying to spot these gaps in your own culture is like trying to take a picture of a black hole — very difficult by the very nature of the thing. So I was practically jumping up and down when Melzer delivered this one to my doorstep: people in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance knew how to read each other and the ancients, and we just…don’t.

Esoteric reading isn’t just rarely practiced these days, it sounds vaguely…unseemly. Like something a superstitious rube would do, adding up the numeric values of letters in Bible verses to find God’s hidden commandments and that sort of thing. So I think one of the greatest contributions Melzer makes is to convince us that we read esoterically all the time. I’m going to reproduce kind of a long quotation here because it’s just so good at conveying what esotericism is and how it’s the most natural thing in the world:

Imagine you have received a letter in the mail from your beloved, from whom you have been separated for many long months… You fear that her feelings toward you may have suffered some alteration. As you hold her letter in your unsteady hands, you are instantly in the place that makes one a good reader. You are responsive to her every word. You are exquisitely alive to every shade and nuance of what she has said — and not said.

“Dearest John.” You know that she always uses “dearest” in letters to you, so the word here means nothing in particular; but her “with love” ending is the weakest of the three variations that she typically uses. The letter is quite cheerful, describing in detail all the things she has been doing. One of them reminds her of something the two of you once did together. “That was a lot of fun,” she exclaims. “Fun” — a resolutely friendly word, not a romantic one. You find yourself weighing every word in a relative scale: it represents not only itself but the negation of every other word that might have been used in its place. Somewhere buried in the middle of the letter, thrown in with an offhandedness that seems too studied, she briefly answers the question you asked her: yes, as it turns out, she has run into Bill Smith — your main rival for her affection. Then it’s back to chatty and cheerful descriptions until the end.

It is clear to you what the letter means. She is letting you down easy, preparing an eventual break. The message is partly in what she has said — the Bill Smith remark, and that lukewarm ending — but primarily in what she has not said. The letter is full of her activities, but not a word of her feelings. There is no moment of intimacy. It is engaging and cheerful but cold. And her cheerfulness is the coldest thing: how could she be so happy if she were missing you? Which points to the most crucial fact: she has said not one word about missing you. That silence fairly screams in your ear.

I love this example because if you received a message from somebody you were very much in love with but you weren’t sure how they felt, not even the most autistic people on earth would fault you for trying to look beyond the plain meaning of the words on the page. It is all too real that a friendly letter could actually mean the opposite (as evidenced by entire subreddits devoted to helping people puzzle out the hidden nuances of an iMessage exchange with a potential lover). This is natural and normal, just as when you run into somebody at a party, their body language and your history with them can tell you that “hey, it’s great to see you” actually means “get the fuck away from me,” and it might even be said in a friendly tone, just one degree cooler than it would have been if they’d meant it.

In our day-to-day social interactions, we’re exquisitely sensitive to this kind of nuance. So it’s actually the most natural thing in the world to apply the same sensitivity to our reading. Every text is the result of a thousand minuscule choices, and some of them are unbelievably careful choices indeed. Speaking as a writer, if you’ve ever found yourself reading something, and gone: “wait a minute, is he implying…” or “hang on, did she deliberately not say…” or “was that word chosen on purpose because it could also mean…” I’m just gonna tell you that the answer is always yes. The only difference between reading and chatting is that when you’re chatting you have all kinds of dedicated neural circuitry that clicks into action to help you parse the thousand subtle implications and nuances of every bit of communication. When you’re reading, you have to force yourself to do it, the way some neurodivergent people train themselves to mechanically and deliberately read social cues. Or you can do what Melzer recommends, and imagine yourself talking to the author, or imagine them writing you a letter. Or imagine yourself writing the thing you’re reading! Would you have phrased it exactly that way? Isn’t that example a little weird? Why did they pick that weird example…?

So it’s actually pretty obvious that every text, of every genre, is imbued with some level of hidden or implicit meaning. The question then is how much, and we can reframe Melzer’s argument as saying that for pre-modern philosophy the answer was, “quite a lot.” If so, there had to be a reason why, because information theory teaches us that packing more bits of meaning into a channel with fixed bandwidth gets harder and harder the further you go. Reading esoterically is challenging, but writing esoterically is no walk in the park either. Some authors do it to give you, the reader, the pleasure of solving a riddle — like Gene Wolfe, probably my favorite science fiction author, whose short stories and novels are all like intricately-crafted puzzle boxes with one story on the surface and another entirely different story hidden inside. You’ve covered two other reasons — the “defensive” and “protective” motivations — sheltering the author from an intolerant reading public, or sheltering society from dangerous and destabilizing ideas. But there’s another whole class of reason, and I think for ancient philosophy it might be the most important one of all.

I’ve repeatedly used spoken conversation as an analogy for esoteric reading, but the analogy also goes the other way. Reading a multi-layered text might be the single best simulation of conversation with the author that it’s possible to create in a non-interactive medium. In a good conversation you’re constantly modeling your interlocutor, predicting what they’re going to say next, jumping in over them to agree or disagree or finish their sentence or pivot the direction, and they’re constantly doing the same to you. There’s a push and a pull, a dance, a connection. A really good conversation is one of the most intimate experiences you can have with another human being, two minds each comprehending the other and being comprehended, alive to every mental sensation and nuance. But reading and struggling with a multi-layered work involves many of the same moves. In order to write esoterically, the author had to anticipate your frame of mind, the exact way you would be thinking, and then leave something there for you to find. For you to find it, you had to do the same thing to him — imagining him imagining you — and so on in infinite regress. It’s like a still image of a single tender moment in a dance, or a snapshot of a climactic exchange in a Chess match.3 You look at this two-dimensional slice, and if you have the skill, a movie plays in your head, you see what must have come right before and right after, like a low-res looping shortform video. It isn’t much, but it’s pretty impressive for something hurled across the millennia by a person long dead.

We’re almost there. The ancients wrote esoterically because esoteric writing is the closest that writing can come to conversation, and the ancients believed that philosophy could only be taught through conversation. Does that shock you? If so, it’s because you come from a culture where philosophy is taken to be propositional knowledge, a set of facts or a list of arguments or a body of knowledge that can be learned. But the ancients considered philosophy to be a kind of process knowledge, like knowing how to dance, or how to ride a bike, or how to do B2B SaaS sales. Imagine trying to learn to play piano by reading a manual but never actually playing any music, that’s how the ancients would think about contemporary academic philosophy. For them, the only way to learn philosophy was to do philosophy with somebody who was already wise — sparring with them verbally, wrestling with them mentally, encountering problems together, solving them together. No text could possibly replace that, but to the extent that any text could, it would have to be a multilayered one. Their works are hard to read because they are fundamentally not designed to directly impart knowledge (!!!), they’re designed to make you, the reader, go through a particular set of mental transitions and moves that imitate the actions of somebody doing philosophy. They’re like the written version of a kung fu movie featuring a multi-tiered pagoda with antagonists of increasing skill on each floor.4 They aren’t training manuals, they are training.

Funnily enough, there is one kind of text that everybody still understands is deliberately written this way. I’m speaking, of course, of higher-level math textbooks. It’s a completely normal genre convention that a good math textbook will leave deliberate gaps in explanations, or huge lacunae between an example and what it’s supposed to show. The reason is identical — these books are not supposed to impart mathematical knowledge in the sense of a body of facts or propositions. Nobody cares if you’ve memorized the statement of some theorem, you can just look it up after all. The books are designed to teach you to do math and they do that long before you get to the exercises. The chapter leading up to the exercises is also a set of exercises, because you can’t understand it without struggling over every word. I am not exaggerating when I say that I once spent multiple days pondering a single sentence in Fulton and Harris’s Representation Theory. Without that struggle, we would not be able to learn, and until very recently every work of philosophy was written in the same spirit.

Reading esoterically is hard. That’s because it’s meant to be hard. That means you have to go slow. Or as Melzer puts it:

Esoteric reading, being very difficult, requires one to slow down and spend much more time with a book than one may be used to. One must read it very slowly, and as a whole, and over and over again. It will probably be necessary to adjust downward your whole idea of how many books you can expect to read in your lifetime.

The issue here is not just the amount of time devoted to going through a book but also the kind — as in the difference between driving and hiking as ways of going through the world. When you journey by foot you are no longer in that automotive state of “on-the-way.” There is a spirit of tarrying and engagement that lets you enter fully into the life of each place as you reach it. This is how you must travel through a book.

Jane: What would a philosophy text that worked like an advanced math textbook even look like? Not quite like the classical works, I think, since many of them were intended as aides memoire to consult after you’d worked through the secret teachings with your tutor.5 (There seems to have been a whole parallel oral tradition for interpreting Aristotle, for instance, which we’ve since lost.) But today I don’t know if you could get away with writing something that looked like a straightforward philosophy text but had a secret meaning, simply because in the absence of a cultural memory of esoteric writing anything that can be interpreted as an error from the author will be. You have to somehow clue your desired reader, but only your desired reader, in to the fact that you’re doing this. And while I appreciate your optimism about things one notices in the text being put there on purpose, that’s only true for careful writers — and careful readers. (It’s hard enough getting people to understand the things you explicitly wrote on the page, let alone the things you clearly implied but didn’t quite state; I can’t imagine how frustrating it would be to hide things no one ever finds.)

For esoteric writing to work today, it would have to be something difficult to understand on its very face. It either would have to be clear that the reader was missing something — a book that was vague, or aphoristic, or vibe-y — or else the kind of thing that only makes sense when you already know the things it’s saying. (Though in that case, why bother writing the book?) The latter kind is probably safer, though: my worry is always that in a regime of ubiquitous text, where we’re used to glancing at things for half a second and coming away thinking we understand them, the lazy readers will take real harm from what they think they’ve read.6 But actually I can think of another successful genre that’s meant to encode wisdom but not propositional knowledge: Orthodox Christian theology.

Here’s the difference between Catholicism and Orthodoxy: Catholics think the difference between Catholicism and Orthodoxy is the Pope and the filioque, and the Orthodox think the difference between Catholicism and Orthodoxy is that Catholics think the difference between Catholicism and Orthodoxy is the Pope and the filioque.7 It’s not that there aren’t doctrinal differences (you can read Fr. Thomas Hopko’s rundown here), but it’s mostly a question of approach: Catholic theology is an academic discipline devoted to reasoning about God, and Orthodox theology is a practical pursuit intended to communicate something that helps the reader in his metanoia, his turning-around of the soul.8 This fact is very difficult and upsetting to many Western rationalists who convert to Orthodoxy, because we keep wanting to reason about God — that’s just how we come at the world, okay? — and the answer from the Church keeps being “you’re doing it wrong.” Personally, though, I’ve needed the regular reminder that becoming Christlike can’t just be something you do with your head. Reason can turn us in the direction of Truth, but it can’t get us all the way there.

I’ve long believed that the Western love affair with reason has its roots in philosophy’s triumphant return to virgin soil: without a thousand years of cultural coevolution with Aristotle, an entire society got one-shotted by 6D dialectical analysis. But Melzer’s treatment of esotericism adds an interesting wrinkle here, because the scholastics and their early modern successors obviously do endorse protective esotericism (which depends for its logic on the conflictual view of theory and praxis). They can’t have been that into reason! So I shall add an epicycle and suggest that when their sheer exuberance about reason’s potential wove itself into the Western intellectual tradition, it inadvertently carried the seeds of its own destruction at the hands of the Enlightenment harmonists. (Of course, “sheer exuberance about reason’s potential” also led to the fact that I can expect all my children to live to adulthood, so you win some, you lose some.)

Anyway, as I think I’ve signposted pretty clearly, I think the conflictual view is the right one. We can never bring our social and political world into full harmony with reason, because at some point it must rest on on something that doesn’t actually hold up to close examination. And that’s — well, not okay, it’s a tragic flaw at the heart of the human condition, but have you heard that we live in a fallen world? Tragedy is inevitable.

It’s hard to see the conflict today, though, because we have so few shared pieties left. Marriage, family, patriotism, faith, any and all normative social roles — they’ve all foundered on the shoals of the free and open society’s “you just do you, man.” Sure, it’s fine to do those things (mostly, as long as you’re not tacky about it), but it’s also fine not to. There’s no need for esotericism to protect a people who can no longer be shocked. The ancients understood the philosopher to outside of, and subversive to, the city, but the modern city is founded on the notion of subversion. The limited liberal state is what’s left when the process of emancipation has run its course and the shared conception of a “right way” to live has been stripped away. But look — as creatures of the modern world, we have all learned to immediately think of all those excluded from the thick community of that “shared conception.” What about the women, the slaves, the metics? Turns out we have shared pieties, too.

John: The challenging thing about discussing this book’s thesis is that the very subject matter itself forces me to put my argument…a little bit elliptically. The first lesson they teach you in internet posting school is “use memorable, punchy, concrete examples with relevance to your reader,” but I cannot do this here. Because if there were certain topics so radioactive, so potentially damaging to the political order that people only ever wrote about them in an indirect fashion, then I would not be able to tell you directly. Doing so would get me doxxed, possibly lynched, and it might even horrify you, my dear. Fortunately we all know that no such topics exist in our society, because we are so remarkably rational and modern, and because nobody writes about them.

Anyway, I profoundly disagree with your characterization of contemporary American intellectual life. There are plenty of views that are considered beyond the pale in polite society and mass culture, even while they’re quietly accepted by significant chunks of the intellectual elite. The exact set of such views has shifted a little over the past few decades, and a little more over the past few years, but I don’t think the number or importance of them really has. If somebody doesn’t recognize this, it’s almost always because they’ve fallen prey to a fish-swimming-in-water effect (either in the mass culture itself, or within their particular alabaster tower). Really, it could not be otherwise.

There has never been a society that wasn’t founded on some lies, and bringing the harsh light of philosophical inquiry to bear on those lies is correctly viewed as anti-social behavior by most people. Most of these people won’t even be persecuting you in a cynical or calculating way. They have believed the lies their whole life, they swim in them and don’t even see them, so when you start doing philosophy in their presence you actually just sound like an insane person. You are babbling and asking what if they sky were blue when everybody can clearly see that it is green, and you are probably a danger to your family and also kind of annoying. It’s true that we don’t literally execute people for having heretical views (mostly), but I chalk that up to greater state capacity and a much more powerful overall system of social control that means eccentrics and other miscreants aren’t much of a threat.

One thing I must emphasize is how fractal this whole setup is and how not on my high-horse I am. In a society like ours, awash in mass communication and with supposedly liberal speech norms, a key goal of esotericism is doing what the military calls IFF and what salespeople call “qualification.” To put it more bluntly: the purpose of public writing is to get yourself invited to the correct group chats. But once you’re in there, the whole dance begins again. Your supposedly elite group of dissident truth-seekers has its own norms, its own shibboleths, and inevitably its own set of foundational and unquestionable lies. Are you stuck now, or are you prepared to lose your cool new friends and ascend to Level 2? This is what separates the men from the boys, the merely disagreeable from the true lovers of wisdom. It’s a hard road to walk: finding those whom you thought were your people only to lose them again. I’m not quite strong enough or autistic enough to do it, which means I would’ve been one of the juvenile delinquents hanging out with Socrates, not an actual hemlock-drinker. I have tremendous respect for those who can go all the way.

So is that the distinction then? Is the whole “conflict” between theory and praxis, between philosophy and society, all about protecting an elite of high-functioning truth-seekers who are trying to find and communicate with each other amidst an ocean of unreflective philistines? Melzer claims that this is how the ancients thought, and that much of the decline of esotericism is explained by moderns no longer feeling this way. What is he smoking? Has he never been around a group of people talking about how to preserve NPR funding? People love this framing because it flatters them, makes them feel like they are part of a special group of wise sages pondering the secrets of the universe, as opposed to those rubes who just want to watch football and grill (and persecute heretics). People have always thought this way, from Plato’s “bronze souls” to Hillary’s “deplorables,” and people probably always will think this way. But it isn’t why we need esotericism.

The reality is much darker. Mobs don’t form spontaneously, they are whipped up by agitators. Within the circle of people who think and talk a lot about ideas, there are some who are motivated by truth, and some who are motivated by something else. The ivory towers of academia teem with witchhunters, and I’m afraid your totally based Signal chat does as well. They are not ignorant, they are not unreflective, they are as wise as snakes and as merciful as Great White Sharks. They understand exactly what you are saying, they may even agree that it is true, and they will use it to hang you anyway, because they are just playing a different game from you. The conflict isn’t between the enlightened and the many, it’s between two different camps within the enlightened. The natural enemy of the man who hungers for truth is not the rube who hungers for football and burgers, it’s the equally impressive man who hungers for glory (or for what he thinks is glory).

It took me embarrassingly long to understand that this is how the world works, because while like most people I’m a blend of the two types, by nature I incline more toward loving truth, and it’s hard for each side to comprehend the other. If you’ve ever complained about “entryism” in your academic department or seen an intellectual community turn into a group of frothing ideologues, it usually isn’t because everybody just lost their minds at once. There are people who knew better and who did it on purpose, because the manipulation of social reality (and its concomitant rewards) is more interesting to them than your research project. The ancients knew this too — political excellence and philosophical excellence are like oil and water: they can be held for a time in an uneasy emulsion, but their natural tendency is to shrink with loathing from each other. And the nature of political excellence means that they will always win, so the philosophers need to hide. That’s why you need esoteric writing.

The moment the scales fell from my eyes, actually, was the SARS-2 pandemic that we all lived through, but which now feels like a weird dream. One of the most dreamlike parts for me was the first few weeks, when the plucky right-wing dissidents were loading up on N95 masks and sharing graphs of doubling times with each other, whilst the center-left loudly made fun of them and declared that anyone worried about the virus was a racist. A few weeks later, everybody had exactly switched sides with zero acknowledgement or discussion, and I began wondering if I was a crazy person. A few months after that, mass outdoor gatherings suddenly switched from being subversive to patriotic, and that was when I realized that my entire life the social reality in which I had swam was actively shaped by powers with no regard for truth or reality. It wasn’t that they were against the truth, or trying to cover things up on principle, it was even weirder than that. It was just orthogonal to what they cared about. They were genuinely indifferent. They existed in a world of arguments and reason just like I did, but in their world these were tools for winning rather than tools for discovering the nature of things.

I remember one guy in particular, an acquaintance who lived near me. One day in June he posted an angry tweet about the wicked people who went outside and breathed on each other. The very next day he posted a video of him screaming within a mob of thousands of people, with a message denouncing the wicked people who were not joining them. This guy wasn’t dumb, wasn’t a brainwashed normie, his job was to convince people of things, and with a start I realized that he just didn’t care and that the world was full of people like him, and that that kind of explained everything. But guys like that aren’t just on Twitter, they’re everywhere, including your super secret philosophers’ club. And this, I think, is the true meaning of the “conflictual view” — it isn’t that you need to write esoterically to avoid transgressing the pieties of the normies, it isn’t even that there’s a bunch of lawful neutral Inspector Javerts out there acting like Plato’s guardians and hunting down dissidents for the good of the many. The wolves are right here, and they’re dressed up like philosophers. They’re your colleagues, your teachers, your students. To let your guard down and write plainly is to make yourself very vulnerable to these people, as countless poor quokkas throughout history have learnt.

Jane: Okay, let’s grant that you’re right and — despite the fact that there are people out there putting their real government names to takes like “the Holocaust is a lie invented by the Jews” and “an evil scientist created white people in a lab” — there are things you just can’t say.9 There’s obviously a level on which that’s true: you’re never going to get tenure or make partner or be elected dogcatcher if you’re on the record with some of these crazy opinions. On the other hand, you’re also not at risk of prison, execution, or complete social death the way a premodern heretic would have been. But fine, maybe these days we’re just better at keeping the velvet glove over the enforcement of pieties. Maybe we’ve figured out how to put the policeman in everyone’s head instead of on the street corner, with tremendous savings on real estate.

What then is the truth-seeking philosopher to do?

I’m going to offer two examples here, carefully calibrated (I hope!) to evoke some visceral reaction in our readers without actually prompting anyone to show up at our house with torches and pitchforks. So let’s take the Constitution.

As is the tradition of my people (overeducated dilettantes), I once considered going to law school — not because I wanted to actually practice law but because I enjoy arguing about ideas. Luckily I came to my senses and got my MRS instead, but I did spend a lot of time reading about constitutional theory and interpretation and realized to my horror that none of it makes any sense. In theory the law binds us because “we,” the vast diachronic entity called the American people, have agreed to be bound by it. That’s why the originalists say we need to know what the people who signed up thought they were agreeing to, since that’s the extent of the law’s legitimate authority today. But push even a little bit and the originalists will admit that no, it really boils down to the fact that we all think we’re bound by it. Political legitimacy derives from…the belief in political legitimacy. It’s turtles all the way down. Any attempt to delineate neutral interpretive principles is just an elaborate attempt to meme society at large into tying its rulers’ hands, a willingness to limit the options available to Our Guys if it means political pressure will force Their Guys to operate under the same constraints. It is, in short, a lie.

But you can’t say that; you can’t point it out; the trick doesn’t work if you tell the marks it’s happening. We’ve all agreed that the Constitution is binding, which limits the potential range of our fights to “things the Constitution might plausibly be interpreted to say” — a range that can be stretched, certainly, but not infinitely far. Which is good! I am in favor of the kind of stability that comes from political disagreement happening between men in suits filing briefs instead of men in camo firing guns. But that doesn’t make any of it actually true. It just makes pointing out the lie worse than living with it.

But here’s a counter-example: say your society believes something truly wacky, like that we all live on the inside of the Hollow Earth. This seems like a fairly harmless delusion right up until people start, I don’t know, spending measurable percentages of GDP building rockets that are going to crash horribly because their fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality are wrong.10 At what point is it your moral duty to point at the burning, tangled wreckage that was once a city and suggest that perhaps some assumptions up the line were incorrect? How much does that depend on whether you think anyone will listen?

And more importantly, how do you tell which kind of these situations you’re in? Logically, you can believe in the fundamental incommensurability of theory and praxis, the necessity of some lies, and still try to bring our doubled selves closer to one another. The esoteric philosophers of the past were hardly political quietists: Plato tried to mold the tyrant of Syracuse into a philosopher-king, Aristotle taught Alexander the Great, and Machiavelli was a Florentine official and diplomat who endured torture and exile over his political career. The “turning around of the soul” that enables a man to live for truth can (I’d argue probably should) drive him to live in truth, too, as much as he’s able. But you have to know what you can affect, so you’ll know when to keep your mouth shut — and, I suppose, when to write between the lines.

Before we close, I want to address one final question: does this book about esoteric writing have an esoteric message? Melzer says no, but then he would — putting a big “this book contains a secret message” stamp on your book sort of defeats the purpose of making the message secret. I’m inclined to believe him, though, because he is essentially an Enlightenment lib, a genuine believer in science and reason and democracy. He’s married to anti-Trump thinkfluencer Shikha Dalmia. His acknowledgements thank Bill Kristol and Damon Linker (as well as Harvey Mansfield and dozens of other names I don’t recognize). And he seems perfectly sincere when he describes religious conservatism and political populism as unscientific “assaults on reason.”

In fact, my favorite part of this book is that it isn’t esoteric. It’s fascinating, suggestive, and clearly-argued, but nowhere is Melzer trying to convince us that esotericism is good. He doesn’t even like it; at the very opening of the book he writes that “[t]here are people who have a real love for esoteric interpretation and a real gift for it. I am not one of them. My natural taste is for writers who say exactly what they mean and mean exactly what they say. I can barely tolerate subtlety. If I could have my wish, the whole phenomenon of esoteric writing would simply disappear.” His project is deeper and purer than that, and I find this unutterably charming: imagine spending years of your life writing hundreds of pages about something you don’t even like, because people are wrong and you want them to be right. That’s my kind of philosopher.

For society, anyway. Better for my ego.

My original draft here used RPG source materials as a metaphor — you read the static description of a dungeon, and get a glimpse of what it would be like to have the author as a DM. I deleted this, because it would only be meaningful to those readers who are NERDS.

And then you get to the floor with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

John: This is also true of many math textbooks! Most of them begin as a set of lecture notes, and pretty much all of them are intended to complement intensive, face-to-face tutoring.

I need to find the copy of The Gay Science I marked up when I was thirteen and burn it.

I don’t know if it’s the book to read on this, but certainly a book to read on this (insofar as it’s the only one I’ve read) is Pres. Jeannie Constantinou’s very good Thinking Orthodox: Understanding and Acquiring the Orthodox Christian Mind. You have not lived until you have heard a Greek lady rolling the R in phronema.

Don’t @ me, Catholics: I know there’s a genre of Catholic spiritual literature with a similar goal, but let’s not pretend it’s the center of gravity for Catholic theology. Meanwhile Orthodoxy really has nothing like the scholastic tradition.

There are obviously things you can’t say in particular settings, like it would be completely unacceptable for me to drop some of my dank takes on social class over coffee with the other nice suburban Christian moms even if I didn’t use anyone present as an example, but that’s always the case. (“For instance, Shannon, your earrings…”)

As far as I can tell there’s no evidence for the popular story that some V-1 launches went wrong because the trajectories had been calculated for a concave surface, but Umberto Eco claims the Nazis did actually try to find British ships on the other side of the world by pointing infrared telescopes at the sky.

I would love to see just one example of a convincing explanation of a philosopher’s esoteric message. Without that, I don’t feel inclined to spend my time on what seems like an unpromising thesis. (I did read a bit of Leo Strauss once and thought he was obviously bonkers. Wish more Americans would get their history of political thought from Quentin Skinner instead.)

I'm not sure about the claim that "Melzer is not himself a Straussian": I read the Melzer a few years ago and I thought he was *very* Straussian (although I admit that most of my knowledge about Strauss is second-hand, for reasons: https://stephenfrug.blogspot.com/2006/07/on-not-reading-leo-strauss.html). Melzer certainly does more than Strauss to assemble evidence that people wrote esoterically, which is a challenge that I think later interpreters ought to rise to. But he also falls prey, I think, to one of the chief pitfalls of Straussianism: he makes every philosopher sound alike. The exoteric doctrines are all different but in the end the esoteric doctrines all sound the same. Aside from anything else, it can (ironically) make for pretty dull readings.

Another review of Melzer's book is the one by Bernard Yack in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews; I recommend it. (https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/philosophy-between-the-lines-the-lost-history-of-esoteric-writing/) He walks a good careful line, not denying Melzer's (genuinely quite impressive) accumulated evidence (he literally writes "case closed", which is, I think, fair), but also not agreeing with some of Melzer's more outlandish conclusions. Here's a bit of it:

[Meltzer's book] "fails to distinguish between two different kinds of esoteric communication: the extremely common practice of distancing oneself from the explicit meaning of a specific argument or authoritative citation, and the far rarer practice of working out arguments as a continuous undercurrent and corrective of the explicit claims made in a text. Most skeptics, I suspect, might be ready to acknowledge that Machiavelli and Montaigne, Plato and Aristotle, even Montesquieu and Rousseau, do not tell you everything that they want you to take from their writing, that they sometimes plant reasons in their texts to look beyond the more explicit meaning of their words. But few are likely to swallow the notion that all these authors, let alone playwrights like Shakespeare and Sophocles, produce works that continuously subvert their most prominent arguments in ways that help readers construct an alternative, esoteric argument to take their place. And with good reason. For this kind of esotericism is extremely rare. In fact, I do not think that Melzer provides us with a single good example of such an argument. Nevertheless, he leaves us with the impression that the lost continent of esoteric writing he has discovered is teeming with them… In other words, Melzer uses the massive evidence of a relatively limited kind of esoteric writing to convince us of the value of searching for a different, very rarely encountered form."