JOINT REVIEW: Class, by Paul Fussell

Class: A Guide Through the American Status System, Paul Fussell (1983; Touchstone, 1992).

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

Jane: People are always saying that Americans don’t like to talk about social class. In some sense this is true: we’ve never had a legible and clearly-articulated class system along English lines, and we pride ourselves on our society’s mobility. (Well, we pride ourselves in the ease with which people can move up. The corresponding and inevitable movement down, which is logically required lest everyone should be above average, is sometimes a matter for schadenfreude but never pride. “Ah, America, land of failsons,” said no one ever.) Still, we do have a system of social status — and attempting to limn its details makes people just as uncomfortable today as it did forty years ago, when Paul Fussell opened this book by saying that people reacted to the project as if he had said “I am working on a book urging the beating to death of baby whales using the dead bodies of baby seals.”

But in another sense “Americans don’t like talking about social class” is dead wrong. We love talking about class. We just don’t realize we’re doing it.

Classes are just cultures, and like all cultures they are rich in ideas about how one behaves and what one values. Traditionally they run in parallel, fairly siloed from one another — if you’re the sort of person who reads The New York Review of Books you can be pretty sure that the things you read there are addressed to people like you, and ditto People Magazine for quite a different sort of person. With social media, though, we’re suddenly talking across those parallel lines far more than we did before, to great confusion all ‘round. Perennial topics of stupid online debate like “who should go to college and what should they study there?” or “should mothers have paid employment?” or “what should you look for in a spouse and how should you make yourself appealing to your prospects?” all rest so thoroughly on the unstated assumptions of the speaker’s social class that the two sides can’t even settle on the terms of the disagreement.

Our difficulty in seeing this isn’t helped by the fact that we don’t even agree on what “class” means. Something like ninety percent of Americans describe themselves as middle class, but what does that mean? Is someone who makes $100,000 a year middle class? Well, that depends — is that the guy who owns a roofing company and tows his powerboat to the lake on the weekends? The actuary who’s carefully aerating the lawn of the brick colonial he bought in a good school district? Or the orchestra tympanist who spends his summer off at his high school buddy’s house on the Vineyard? Class, properly considered, is all the things that separate these men. Two women may have similar salaries — they may even have gone to the same school and work at the same job — but their class background is immediately apparent in how they dress, eat, decorate their homes, and name their children. (Quick, tell me what Brooklynn’s mother’s fingernails look like compared to Eloise’s mom.) After all, making or losing money doesn’t magically make you switch cultures.

Of course, defining class as culture is itself a potent class indicator. Here’s Fussell:

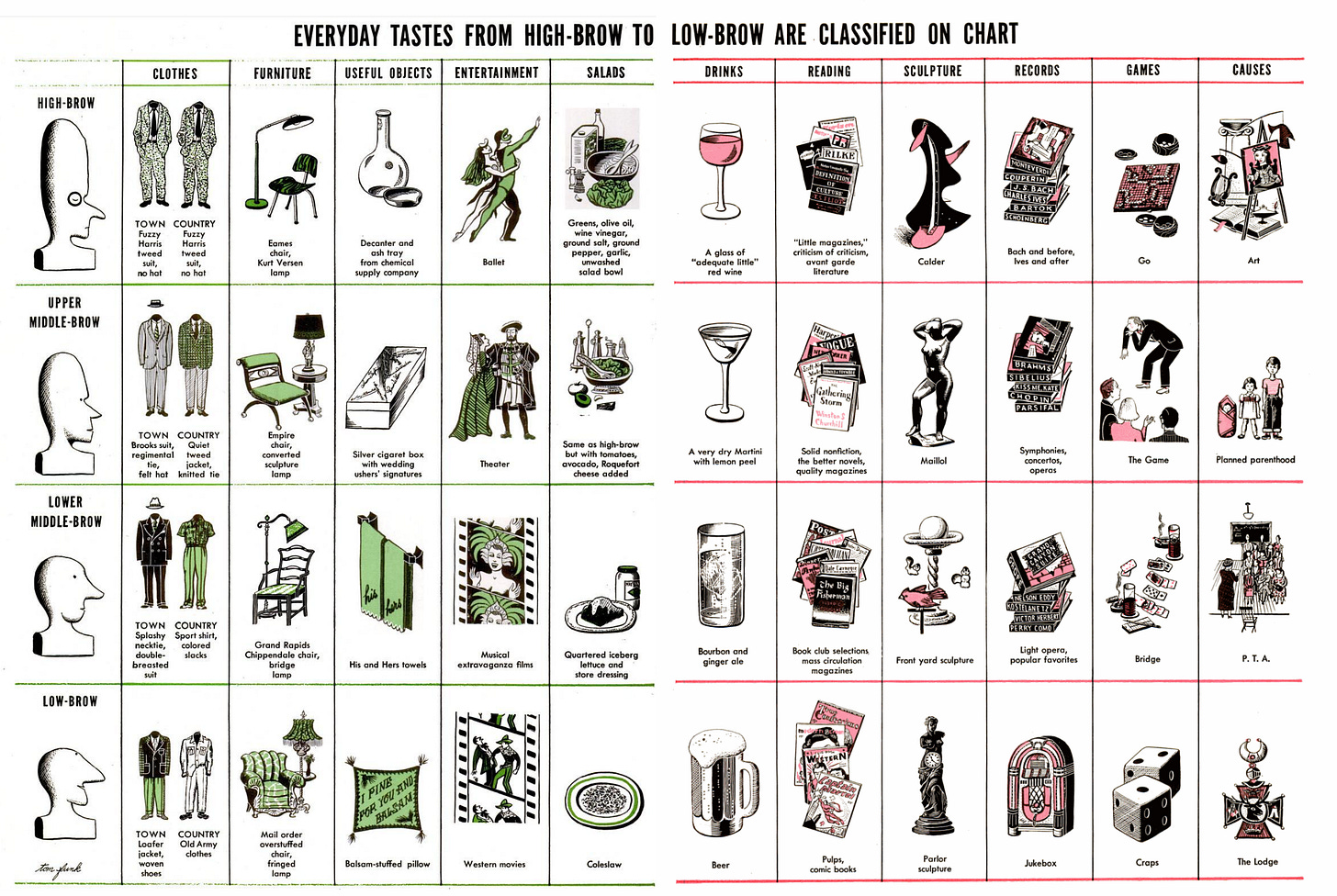

At the bottom, people tend to believe that class is defined by the amount of money you have. In the middle, people grant that money has something to do with it, but think education and the kind of work you do almost equally important. Nearer the top, people perceive that taste, values, ideas, style, and behavior are indispensable criteria of class, regardless of money or occupation or education.

But I’m right, and so is Paul Fussell: social class, as a hierarchical status system, is necessarily defined by the people at the top. It doesn’t matter if you think you’re high — what matters if the people who actually are high think you’re one of them, and they make those determinations based on innumerable tiny indicators that don’t consciously register unless you train yourself to see and analyze them (as, for example, by reading this book). It’s not a guide to changing your class, which is as hard to do as stepping outside any other aspect of your worldview, but just noticing what there is around you will help you to understand the world.

Fussell divides American society into nine classes: top out-of-sight, upper, and upper middle classes all constituting relatively high, then middle class and three degrees of proletarian in the middle, with destitute and bottom out-of-sight at, well, the bottom. The top out-of-sight and the very lowest classes concern him very little, being mostly invisible, but he spends some time distinguishing the others, so let’s give a brief outline so we’re all on the same page.

The upper class is generally wealthy (although class signifiers can outlast a fortune and shabby gentility is certainly a thing), but it typically works in addition to inheriting. Fussell: “It’s likely to make money by controlling banks and the more historic corporations, think tanks, and foundations, and to busy itself with things like the older universities, the Council on Foreign Relations,” and so forth. In most American subcultures it’s considered polite to compliment your hosts, but not so the upper class: praising the food or decor implies you ever doubted it would be anything but beautiful, delicious, expensive, or otherwise impressive. (Besides, they probably didn’t do it themselves.) Bizarre eccentricities are common, either because they’re so secure in their class position that they can afford to indulge personal preferences or as intentional counter-signaling. RFK, Jr. is a perfect example: only someone of the very highest or very lowest classes would put a roadkill bear in the back seat of his car, intending to take it home to eat. (The fact that he didn’t because he was, as the NPR story charmingly puts it, “waylaid by a busy day of falconry,” puts him firmly in the upper, if the fact that he’s a Kennedy wasn’t a giveaway. The Bushes are also upper class. The Pritzkers are too fat.) And although the upper class may occasionally produce a thinker, they are generally profoundly anti-intellectual; academic or literary achievement is regarded as a personal idiosyncracy akin to collecting beetles, not a load-bearing part of class identity.

The upper-middle class, by contrast, considers education — or at least the appearance of education — integral. This is the class of doctors, lawyers, and architects, financiers and shipping magnates, but also (at the poorer end) university professors, journalists, and those who work in “the arts.” Anyone who voted for Elizabeth Warren is upper-middle class, as is anyone who is delighted to tell you they don’t own a television. (The television itself is perhaps a less reliable indicator than once it was, because we now have so many more glowing rectangles in our lives; it was the telling people about it that was upper-middle.) Upper-middles do things like name their dogs “Phaedo.” Upper-middle class mothers usually work, and they regard their jobs as contributing as much meaning and purpose to their lives as do their children (even if their husband’s salary dwarfs their own income). Upper-middle class teenagers go to college, and typically major in things with no obvious commercial application like English, art history, or computer science. The upper-middle is the class that people mean when they talk about “elites,” and it may be the class whose specific visible cultural markers have changed most since 1983, but the ethos remains: a pride in their own sophistication, mixed with a certain bourgeois sense of shame. Like the upper class, the upper-middles may have trust funds; unlike the upper class, they are embarrassed to admit it.

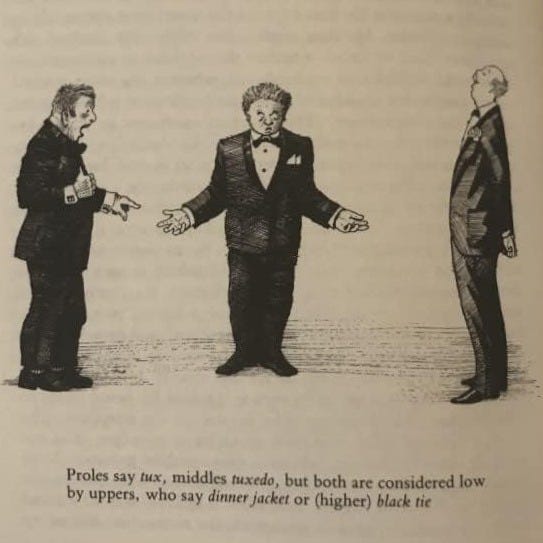

The middle class, per Fussell, is “distinguishable more by its earnestness and psychic insecurity than by its middle income.” It is desperate to be correct and respectable, whatever that means in its particular context: one can become very wealthy indeed without ever leaving the middle class at all. The Koch brothers are middle class, and not just because they come from Wichita. Impressive displays of Christmas lights or a perfectly manicured lawn are telltale signs of a middle class house, which the middles will invariably refer to as a “home.” Anyone who has opinions about their neighbors’ garbage bins is middle class, as is anyone who goes around publicly opining on whether things are trashy. (I once enjoyed spectating at a fourteen-page internet argument over whether it was trashy to serve potato salad at a 4th of July barbecue.) The middle class loves euphemism and commercial jargon, which it thinks denotes sophistication — where uppers die, have sex, or buy shoes, middles “pass away,” “make love,” and purchase “footwear.” (Middles also purchase “flatware,” but uppers inherited their silver and would not discuss it anyway.) A mother who packs her child a lunch of sliced dry salami, water crackers, and manchego might be upper-middle class, but if she makes a point of calling it “charcuterie” she’s middle. Premium mediocre is middle class. And if this all sounds rather snippy — Fussell really has very little nice to say about the middle class, whom he blames for (among other things) “the euphemism, jargon, gentility, and verbal slop that wash over us” — there’s still something to be said for the middle class’s deep desire to fit in. They are the class of Mrs. Grundy (whose first name, in our more informal age, has been revealed to be “Karen”), and they are either the absolute mainstay of our culture or the final boss of someone else’s. Nothing can survive without a group of people anxiously devoted to maintaining it.

Below the middle class are the proles. Fussell divides them into three tiers: high proles are skilled craftsmen afraid of losing status, mid-proles are simple operators like factory workers or bus drivers afraid of losing their jobs, and low proles are in precarious or uncertain employment afraid of never moving up or earning their freedom. High proles are proud of their independence and their ability to earn a living with their hands, and they share the upper class’s scorn for the way the middle class worries about convention. Nursing, policing, and the skilled trades are the quintessential high prole occupations, which is why telling an upper-middle class father that his son should become a plumber is perceived as such an insult. Proles love wearing shirts or hats that bear messages or even just a brand name: Fussell writes that brand names “possess a totemistic power to confer distinction on those who wear them. By donning legible clothing you fuse your private identity with external commercial success, redeeming your insignificance and becoming, for the moment, somebody.” This goes double for bumper stickers, which are used to convey important facts about the driver on the machine that is an extension of himself. (The middle class also enjoys legible clothing, but they’re more restrained about it: a Coach bag is middle class, but that print with all the C’s is very prole. And only stickers for mainstream presidential candidates and children’s schools or activities are permitted on the middle class automobile.) Camping and hunting are prole; fly-fishing is upper or upper-middle but bait (“regular”) fishing is extremely prole. (Okay, fine, in the few parts of the country where there’s still mounted fox hunting, that’s upper class.) Wealthy proles (or “kulaks”), of whom there are many, indulge in motorboats and ATVs. They prefer new-builds on lots without old trees that might drop leaves in their gutters or fall on the house. They are blessedly free of middle class status anxiety, and feel free to do what they like and buy what they please. Unfortunately they have absolutely no taste. Donald Trump is a prole.

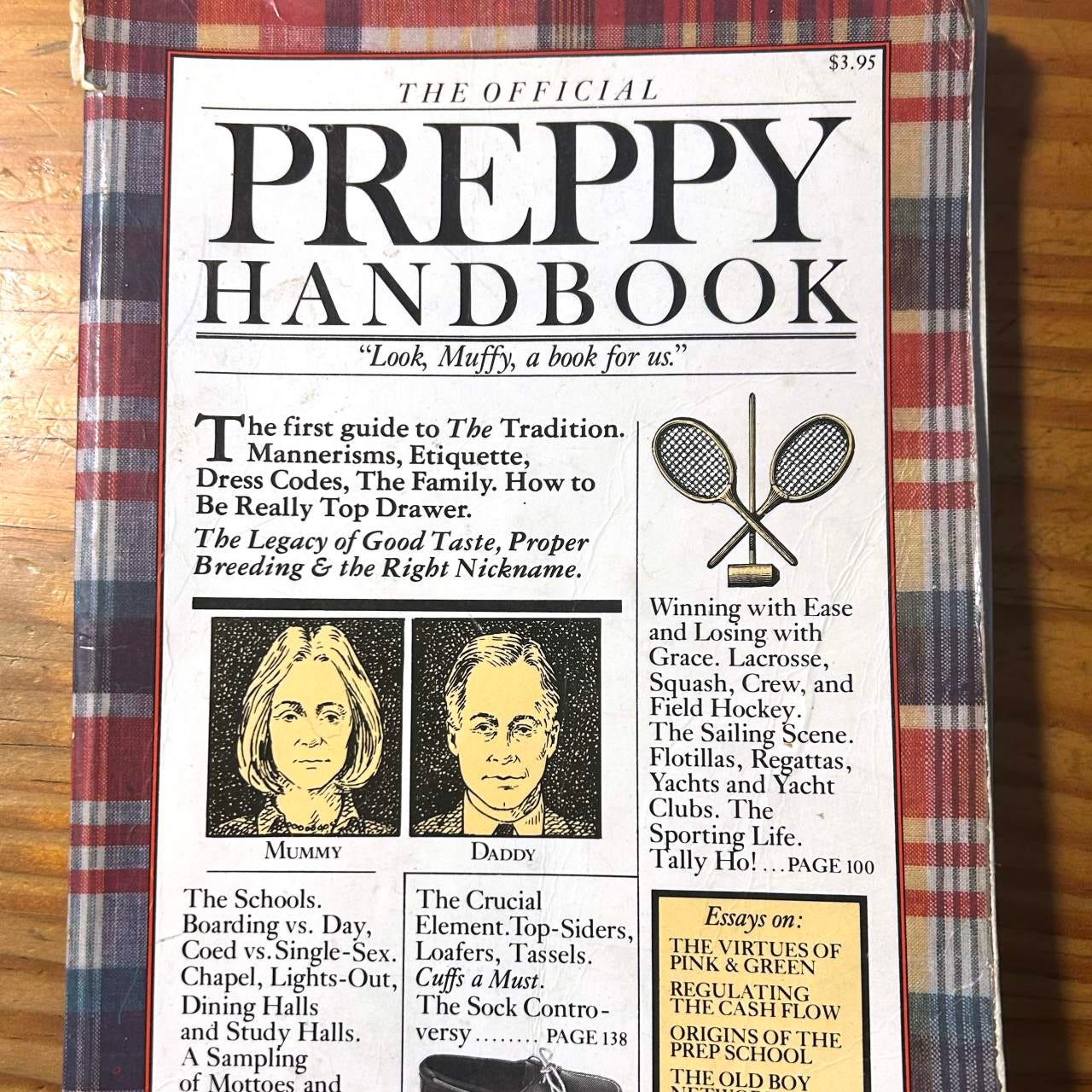

Many of the specific class indicators of 1983 have fallen by the wayside (the Official Preppy Handbook is no longer a good description of the upper-middle class), but the broad strokes remain: things are higher class if they are natural as opposed to artificial, if they are labor-intensive to use or maintain, if they are old, and if they are understated. A grass lawn is classier than Astroturf. A wool sweater is classier than a cotton sweatshirt, which is classier than a nylon jacket with a Nike logo. A creaky Victorian is classier than a newly built house, even if they’re in the same neighborhood. A sailboat is much classier than a powerboat. However, “classy” as a laudative is prole. The middle class says “tasteful,” and the upper-middle and upper classes just say “nice.”

John: It can be painful to have what Edmund Burke called the “decent drapery of life” torn away from you. For example, legend has it that playing too many FPS games can result in a kind of reverse pareidolia where the people you see in real life begin to seem like inanimate objects: lifeless marionettes or sacks of flesh. In one sense, this is a true way of seeing — after all, there is a level of description at which people really are just big salty bags of chemical reactions feverishly maintaining homeostasis. But being stuck in that mode of perception sounds like Hell. So you need to be careful what media you permit into the castle of your mind, because some of it might change the way you view people or society for the worse, might tear away pleasing illusions, might infect you with memes from which there is no going back.

A benign version of this is that ever since I read that book on clouds, I’ve been unable to just lie in my hammock and look at a pretty white cloud without thinking to myself, “Interesting, a cumulus congestus already and it’s only 1pm, somebody east of us is gonna have a stormy night.” But when the subject is people or culture rather than clouds, you may come to regret your new way of seeing. James Scott made it impossible for me to read ancient history without thinking of the barbarians as the victims, and Edward Luttwak made it impossible for me to read the headlines without thinking of Canadian and European sovereignty as a cruel joke. Whenever this happens, you’ve gained something but also lost something. Sometimes it’s nice to live in a world of fluffy clouds and pretend countries, without having your face rubbed in the disturbing reality beneath.

Fussell’s book is dangerous in just this way, and should be plastered with biohazard symbols and only sold in brown paper bags by surly clerks who give you a judgmental glare. Before reading it, you can drift serenely through society, unencumbered by analysis. You do the things you do because that’s just how you are, and others do the things they do, and some of them annoy you, and others seem familiar, and yet others make you feel small, but it’s all just random and uncorrelated, right? After reading this book that world is dead, that option is gone. You can now sense the currents of power and mimesis that churn around every social encounter, like those weirdos with the magnets in their fingers who can sense the location of your wifi router. Your innocence is lost, your delusions are gone. The other day when I suddenly had to spend too much money taking our children to a concert featuring works by a composer I don’t even like, for no reason other than that I felt it was important for children to experience the arts, I suddenly felt a dreadful chill and knew why I was doing it.

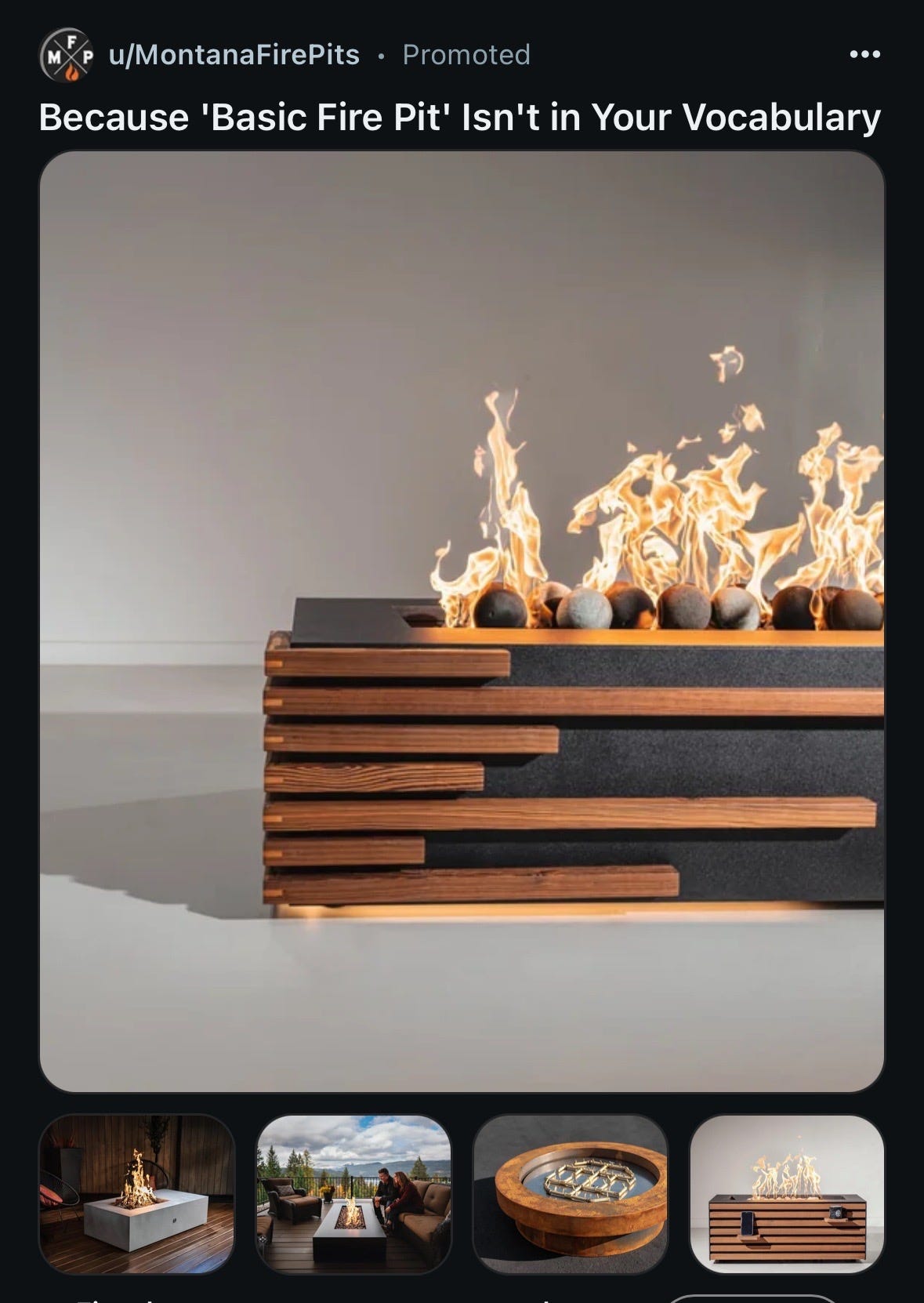

This book has even ruined Reddit for me. Yes, plain, simple, innocent, retarded Reddit. Fussell quotes an advertisement 40 years ago: “Create a rich, warm, sensual allusion to your own good taste that will demand respect and consideration in every setting you care to imagine.” It's hard to imagine a more pathetic striver appeal to status anxiety, but then I crashed into a Reddit ad for a firepit from this company.

What’s so striking about this is that it says nothing about the qualities of the product at all. The entire ad is about how this firepit will cause the other people in your life to stop regarding you as “basic.” Of course, “basic” is contemporary code for “middle-class,” making this an unusually blatant status pitch. And of course, like all status pitches, it's a lie. A product claiming to move you from Class N to Class N + 1 is almost invariably just cementing your place in Class N,1 and sure enough a gas firepit with faux-modernist styling is roughly the most middle-class thing ever.2

What makes the firepit so heartbreaking is that it’s almost an example of attempting upward mobility the correct way, since — as you note — in the upper echelons of the American class system, taste and style and behavior are what really stratify people. The problem is that the purchaser lacks the class background to understand the shibboleths and so gets led terribly astray. It’s like some poor fool trying to seem very educated and cultured by reading The New Yorker (if you want to impress, try the New York Review of Books, or better the London Review of Books).3 This information asymmetry is what defeats so many attempts at direct social climbing. You can’t make a frontal assault on the class above you. They will see you coming.

What can you do then? There is a technique, which I like to call “laybacking,” after a particularly strenuous way of climbing a crack in a rock wall by simultaneously pushing and pulling. It’s analogous to the observation that only losers try to climb a corporate hierarchy directly. The real trick is to ascend via a zig-zag motion, bouncing between a number of different companies, because getting poached away for a job one level above your current one is perversely easier than getting promoted where you are. Well it’s the same with status hierarchies, social class chief among them — if you want to improve your position, the trick is to find multiple incommensurate status hierarchies and use your position in one to slightly improve your position in the other, and then switch directions and use your newly improved position in the second to boost you in the first.

It’s like Andreessen’s advice that you become a double threat,4 but for a much cattier and more zero-sum form of progression. If you want (say) both rich people and academics to think you’re a big deal, you should tell the rich people about your academic achievements and the academics about how rich you are. But for this to work, it’s vital that the parallel ladders be truly incommensurate. If people in hierarchy A and hierarchy B know each other, or understand each other, or have dealings with each other too often, then your whole scheme will collapse. The key ingredient is the ambiguity. If they aren’t sure what your position on the other totem pole means, they will err on the side of caution and treat you like a bigger deal than you are. Foreign countries are great for this purpose (one reason ambassadorships are a hot commodity for the dedicated social climber), as are religious or artistic movements. If you show up to a cocktail party wearing a songkok and bearing a certificate declaring you to be the Grand Poobah of Brunei, nobody will know what it means, and they will enter an infinite loop while trying to compute your relative status before finally shorting out.

Anyways, back to taste, the striking thing to me is that these distinctions are all collapsing, as increasingly large numbers of Americans all listen to the same music, watch the same YouTube shorts, and read the same tweets. Fussell was already tuned into this back in his era, and called it “prole drift”: the tendency in the United States for all classes to drift downwards over time. Perhaps we can explain it via the barber-pole theory of fashionability spinning in reverse, with the highest classes emulating prole tastes to shock the middles, who eventually can’t help themselves in aping what they now perceive to be high. I think you see something like that process in many places, here’s a concrete example: underclass guys like NWA invent gangster rap → very posh kids shouting rap lyrics ironically → midwits embracing rap-inflected cultural products like Hamilton and Beyoncé completely sincerely. The middles and the uppers are doing very different things here, but at the end of the day everybody is listening to rap.

But it isn’t just the proletarianization of all media (obviously supercharged by the internet and by porn), simultaneously there's a loss of dynamic range on the high end. A couple paragraphs ago I jokingly parsed out the differences between the NYRB and the LRB, and once there would have been a lot of people laughing along. Today there are many fewer such people. Classical music once provided countless opportunities for snobbery and meta-snobbery, but these days when I attend a concert the average age is about 85. It’s even worse in the universities: say what you like about the boomer professors, they may have hated their civilization and wanted to destroy it, but they at least understood what they were trying to destroy. In contrast, the new generation are, as Helen Andrews once memorably put it, “pretty dumb”:

I mean that the majority of meritocrats are, on their own chosen scale of intelligence, pretty dumb. Grade inflation first hit the Ivies in the late 1960s for a reason. Yale professor David Gelernter has noticed it in his students: “They are so ignorant that it’s hard to accept how ignorant they are. It’s very hard to grasp that the person you’re talking to, who is bright, articulate, conversable, interested, doesn’t know who Beethoven is. Looking back at the history of the twentieth century, just sees a fog.” Camille Paglia once assigned the spiritual “Go Down, Moses” to an English seminar, only to discover to her horror that “of a class of twenty-five students, only two seemed to recognize the name ‘Moses’.… They did not know who he was.”

“Dumb” is the wrong word here, what she really means is "ignorant." But ignorant of what exactly? Why does it matter that you know who Beethoven is (and that you be able to recognize even his lesser-known works from audio alone)? Well, even if you think the information has no objective value, it once marked you as a member of a particular culture. So what do we make of all this flattening? Does it mean that that former culture is dying? Or have its secret code words just changed? And if it is gone, does that make America more egalitarian than it used to be? Or has a different, alien culture just seized the top spot?

Jane: The former top culture has certainly failed to perpetuate its specific markers, but that’s nothing new. Once upon a time it used to be really important to be able to dance, bow, and even walk “correctly” — who cares about that stuff now? A hundred years ago, incredibly baggy pants briefly bespoke class and sophistication. And when Fussell was writing, a mere forty years ago, catching a glimpse of Burberry check was a clear sign that you were dealing with the upper (or at least the upper-middle) class. That’s definitely not true today.5 And yet the top culture remains the top culture: it’s just the visible manifestations that have changed. (Incidentally, and this is counter-intuitive, the “top culture” — the people who are producing and patronizing the culture-makers like artists, philosophers, novelists — is that of the upper-middle class. The true uppers, whom Matthew Arnold famously called the Barbarians, are marked by what Fussell terms an “imperviousness to ideas and [a] total lack of interest in them.”)

The real question is why the culture changed, and what it changed to. Because yes, there’s obviously some element of prole drift and we’ve undergone a great flattening: American culture has in general become less formal, the desire for upward mobility means that any marker of high status will be aped by those on the lower rungs until it loses its cachet, and the Internet has eaten everything. (Fussell laments that “there used to be different audiences for different things.” Oh, if only he knew.) But in fact I think the answer is hidden in the final chapter of Fussell’s book, which he titles “The X Way Out.”

Way out of what? Well, of class, of course. Becoming an X person, joining Category X, is your only way to escape! X people, Fussell tells us, are talented bohemians, independent-minded, an unmonied aristocracy drawn from all classes but rejecting all their conventions. X people just do what they like, regardless of what their class script says they “should” do. They “adopt towards cultural objects the attitude of makers, and of course critics.” They are “independent-minded, free of anxious regard for popular shibboleths, loose in carriage and demeanor.” They are self-directed, so they pursue “remote and un-commonplace knowledge—they may be fanatical about Serbo-Croatian prosody, geodes, or Northern French church vestments of the eleventh century.” So far, so good — you can probably add “weirdly into hill people” to that list.

But then Fussell starts to get into the details and my eyebrows start to rise. X people, he writes, reject bourgeois convention about things like dressing properly for the occasion: an X person’s outfit always “conveys the message ‘I am freer and less terrified than you are,’ or—in extreme circumstances—‘I am more intelligent and interesting than you are: please do not bore me.’” X people wear their babies, decorate their homes with exotic textiles, and cook Turkish or vegetarian or Thai food — preferably organic. And they prefer to cook at home, because they “go in for a lot of things you can’t readily get out, like herbal teas, lemon-flavored vodka, and baked goods made of stone-ground flour.”

For some reason, at this point I suddenly remembered that I had not yet unpacked my groceries from my Whole Foods run, so I had to put the book down for a minute.

It’s pretty obvious what happened here: sometime after Class was written, the upper-middle class adopted the trappings of Fussell’s category X. In fact, we can roughly pin down the date — when the book was published in 1983, the upper-middles had just been lovingly lampooned by The Official Preppy Handbook. When Metropolitan came out in 1990, the UHBs were manifestly still the same people doing the same thing in the same way (though they were beginning to worry about “the death of the preppy class”).6 But by 2001, when David Brooks’s Bobos in Paradise described the new “bourgeois bohemians,” behavior that had once been a counter-cultural thumb in the eye of polite American society had become polite American society. Suddenly everyone was doing yoga and buying organic groceries and having gay friends. Women whose own mothers would have disowned them for premarital cohabitation were hoping their daughters would move in with a boyfriend because it might be the first step to grandchildren. The defunct blog Stuff White People Like is the bobo Official Preppy Handbook (though it isn’t as funny, which is why its book version didn’t do the same numbers). Forget about boat shoes and country club memberships: now it’s all about artisanal coffee, hummus, and riding your bicycle to work.

Or at least it was. Now everything that was hip in the ‘90s and the ‘00s has moved inexorably down the status hierarchy, which means you need innovation at the top — once people get the idea that eating ethnic food is a cool thing to do, you have to move on from the now-prosaic Thai and Indian to the still-exotic, like Bhutanese or Uzbek. (Other examples of this phenomenon are left as an exercise for the reader.)

But in a weird way this gives me hope, because it’s proof positive that sometimes you can change the top culture just by doing your own thing and being visibly cool. And yes, part of the shift is a change in the actual makeup of the upper-middle class — Brooks ascribes a lot of it to changes in Ivy League admissions policies in the second half of the 20th century — but many of today’s upper-middle are the children and grandchildren of the preppies. (Class position has a remarkable way of persisting across apparent cultural changes: if the entire Cultural Revolution wasn’t enough to dislodge China’s elites, I don’t know why anyone would expect the move from Greenwich, Connecticut to Williamsburg to do the trick here.) It’s just the signifiers that have changed, so being on top doesn’t look the same. Which is great news for the people who like those signifiers for their own sake! If you think that recycling and buying fair-trade coffee and going to therapy are actually good, then you’re delighted when they become markers of cultural sophistication. Now everyone wants to do the good thing! Does it even matter if they’re doing it for social signaling rather than out of moral conviction?

All of which sheds interesting light on the idea that we can solve America’s birth dearth by making motherhood “high status.” I hope the preceding five thousand words of this book review have made it clear why that’s nonsensical (at least if you take it in the baldest terms), but in case it hasn’t I’ll spell it out: status in the American class system comes not just from what you do, but how you do it. Even things like “going to college” or “being rich” aren’t enough to make you high class, and those at least tend to bring with them status-enhancers like spending your time in independent and autonomous pursuits, or freedom from physical toil. Motherhood emphatically does not do that. In fact, it does more or less the opposite. The parts of the maternal experience that are most universal across time, space, and class lines are the ones that involve the most interruption, limitation, and wiping of butts and noses, none of which is the kind of thing that’s ever going to imbue status.

And yet women of all social classes still have kids (…for now), and like everything else different classes have different ways of raising them. The current trend, which everyone feels like they ought to emulate because it’s practiced by the upper-middles, is for an approach that’s so high intensity and high investment (in both time and money) that it’s hard for even the wealthy to manage it with more than two — and borderline impossible for anyone farther down the hierarchy to do at all. But even if we’re never going to make motherhood qua motherhood high status, history suggests that we might be able to change the way women who are already high status raise their kids and it’ll eventually bubble down to everyone else. (This is what you suggested last time we wrote about this; I was unconvinced then, but I’ve come around.) Those changes almost definitionally can’t make actual high-status motherhood “more accessible,” because anything that everyone can do won’t work as a status marker, but if upper-middle class parenting borrowed a bit from the category X vibe of “I am freer and less terrified than you are,” the way upper-middle class clothing already has — if there were a little less intensity and a little more sprezzatura — if the flex became not how many instruments, extracurricular activities, and European trips your children experienced but how full and joyful life was with your vigorous brood — there might be a few more babies.

Do I think this is likely to happen? Not really: the structural forces pushing for ever-greater parental investment are powerful, and small children make it hard to do many of the things that do convey status. But even a few more women deciding they don’t care about the standard script and becoming “X moms” in an act of glorious self-barbarization would be good for us.

The trouble with becoming a X person of any sort is that you need to know exactly what the rules are — and at the same time, you have to not care about them at all. This more or less means you have to be either a disaffected member of one of the higher classes (or someone who’s spent enough time with them to understand their ways); after all, proles don’t mimic the status displays of the upper-middles either, but that’s because they’re following their own scripts, not writing a new one.7 Doing exactly as you please, thumbing your nose at silly conventions, flaunting your freedom from the standard American ways of displaying status, is only cool if you’re obviously doing it on purpose, and the best way to do that is subtlety. If you show up at a fancy party in jeans it might simply be because you didn’t know what to expect, which is neither classy nor cool. Better to wear a suit when most men are in black tie, or a sportcoat if they’re in suits — something that makes it clear you’ve understood the brief but chosen to ignore it.

Clothes aren’t a good example any more, though, precisely because the widespread adoption of what were then category X markers means our shared norms of dress have all but disappeared. (The guy who shows up at the fancy party in jeans might be trying to imitate X/bobo nonchalance and not hitting the notes quite right, or he might be brashly signalling his distaste for this effete nonsense, both of which are even more cringe than not knowing the rules in the first place.) But my point remains even if you have to interpret it metaphorically! Today’s X people show that they are X people by quietly breaking social rules about things people actually still care about, like college admissions or the correct political opinion. Putting an “I bought this before I knew he was a Nazi” bumper sticker on your Tesla is middle class, indicating your deep concern with social respectability. The upper-middle thing is to put it on your Ford, a cleverly ironic gesture that simultaneously displays your historical knowledge and mocks middle class status anxiety. To be category X today, you’d have to put it on a Volkswagen.

John: Ah, we’ve finally gotten to politics. The curious thing about American politics is that it’s the exact opposite of media and the arts: political class-coding and class segregation have gotten vastly stronger over time. Only 20 or 30 years ago, both major parties had prominent representatives from every social class, and most classes were split pretty evenly across the parties. Do you remember the “New England Republican”? That was actually just euphemistic code for “upper-middle class Republican,” much as “Reagan Democrat” secretly meant “middle class Democrat” and “Southern Democrat” meant “high-prole Democrat.” Watch either party’s convention, watch their congressional delegation, or their rallies, and there was a pleasing diversity in accent, dress code, and implied social position.

Today that’s all gone: the only classes that are still split anywhere close to evenly are the most ethereal reaches of the upper class (Matthew Arnold's Barbarians) whose imperviousness to ideas means their political stances are essentially random and often held as an ironic affectation; and the very most downtrodden of the low-proles, who are terrified or nihilistic, and either way happy to be wielded as a weapon by one of the major factions. In between, the various classes now tend to break heavily for one side or the other, and this explains a lot about why our politics have gotten nastier and more dysfunctional.

The ideological and activist core of the American left resides in the upper middle class. The American left’s greatest strength (its dominance of culture) and its greatest weakness (its inability to resist capture by totalizing intellectual movements) both flow directly from the strengths and weaknesses of this group. Upper middles are artists, intellectuals, and tastemakers, so the American left dominates the arts and the academy, and it has good taste. Upper middles (as heirs of category X) are also constantly seeking to one-up each other by adopting ever more fringe fashions, which is why the American left is constantly antagonizing 90% of the country with bizarre or destructive luxury beliefs like prison abolition, or like sending male rapists into women’s bathrooms if they say they’re transgender.

Next on the totem pole we have the “true” middle class. Pop quiz: where are they at politically? If your answer is that they’re Republicans, you’re about half a century out of date. That equilibrium was only sustainable back when the upper middles split between the parties, because remember, the fundamental psychic drive of middles is to become upper middles. Now that the upper middles have closed ranks, the middle-middles have eagerly adopted their political beliefs in the quixotic hope that they might be mistaken for them. But as we’ve explained, pretending to be a class you’re not is very hard. The middle-middles always get it a little bit wrong. They espouse the beliefs and shibboleths of the upper-middles in ways that are zany, or off-kilter, or trying too hard, and the result is often disturbing or uncanny. This is closely related to the “hicklib” phenomenon. Most TikTok videos of leftist women saying something utterly deranged are just the contemporary version of the very old story of provincial women trying to imitate their betters and doing it wrong.

But the second main drive of the middle-middles is the desire for conformity and security. Otto von Bismarck famously discovered that the middle class was the most powerful bulwark for small-c conservative politics, and it’s the same over here. So the fact that the American left is an upper-middle/middle-middle alliance is what gives it one of its most paradoxical qualities: its simultaneous embrace of radical transgression and smothering safetyism. The public health and regulatory bureaucracies are major strongholds of the middle class, and since that class now skews left, so do those organizations. In return, they have infected the left with the constricting and suffocating vibe that in Bismarck’s time we would have called reactionary. This partly comes out as zero tolerance for ideological (as opposed to lifestyle) deviance, but it also explains the zeal for minute regulation of everything from showerhead flow rates to workplace conduct. The inventors of Current Thing fads and discoverers of new oppressed identities are upper-middle class, but the people who force you to go along with it or be debanked are solidly middle.

Below the middles, we have the proles, and these days the proles are increasingly right-wing. Donald Trump is an avatar of this transformation, and an accelerant of it, but the ingredients were all there before he came on the scene. High proles are skilled artisans and tradesmen who cherish their autonomy. Mid proles are employees paid hourly, with little control over working conditions and forced to bear the brunt of the smothering bureaucracies (both government and private sector) that control and direct their lives and behavior. As that bureaucracy has gotten ever more onerous and shambolic and demented, the proles have developed a distinctly anti-establishment bent. And as the classes that direct the establishment have gotten polarized to the left, the proles have moved right. This explains many things about the contemporary American right: its populist and revolutionary flavor, but also its wild conspiracizing and its embrace of charismatic showmen and quack remedies. And most of all, it explains its dreadful, dreadful taste.

Consider the MAGA cap: could there be a more prole item of clothing? Number one: it is a baseball cap. Number two: it is in simple primary colors. Number three: it has words on it. Number four: the words are completely, utterly literal. Zero subtext, zero ambiguity. It’s no wonder these things drive upper-middles completely apoplectic with rage. The left-wing equivalents tend to be more passive-aggressive: like those “In this house we believe” signs (a middle-class demand for conformity) or like a Pride_flag-v2-final-FINAL.jpg with colors you didn’t even know existed (an upper-middle flex if there ever were one). The right’s prole-ward drift has happened very fast: Trump rallies are way more prole-coded than the Tea Party rallies of fifteen years ago. I even recall seeing a powerboat rally for Trump,8 which would have been inconceivable in the party of George H. W. Bush.

And the prole character of the contemporary right explains other things, like why they have trouble holding onto their wins. Some people may find that claim controversial, but it’s just true if you zoom out from the day-to-day political fray and look at the trend over the past few decades. A class-based analysis makes the reason obvious: modern right-wing politics in America are basically a peasant revolt, and the one constant throughout history is that peasant revolts never win. This also explains why the American right is so uniquely bad at building institutions (upper-middles build institutions and middle-middles maintain them), and bad — until recently — at seeming exciting and sexy. But that “until recently” is important! Remember how upper middles love to transgress common mores and shock each other with fringe fashions? In the last decade or so, a small coterie of them have discovered that the ultimate transgression is to become right wing. That group has had disproportionate influence on the recent direction of the American right, so disproportionate that it may destabilize the entire frozen conflict that defines American politics. This is the group that Curtis Yarvin has been calling “Dark Elves,” and he’s correct that they have something to offer the right that it cannot achieve on its own.

Anyway, how should we feel about the newly class-based nature of American political conflict? The answer is: very, very bad. Class conflict is so much messier and worse than sectional or ideological or other conflicts. The various social classes of a country are supposed to act together in harmony, and that depends on them seeing each other as part of the same nation. There are a lot of no-good things that happen when that breaks down. To take one example, the upper classes lose all feeling of noblesse oblige, and come to despise the proles. Because they despise them, they seek to replace them, and use mass immigration to weaken their bargaining power. Europe, which has a much older and more entrenched system of class conflict than ours, is farther down this path, and clearly heading towards some kind of social dissolution and serious civil unrest.

And on that optimistic note, anything you want to add before we wrap this up?

Jane: Oh man, there are so many things I couldn’t fit in here. Like the dynamics of baby names (the “reddest” names on this list, like Kyson and Oaklynn, are identifiably prole, though the blue ones read more “ethnic” than any specific class). There’s probably also something interesting to say about class-linked behavior on social media, starting with platform and frequency and extending right on up to the nature of one’s #content. Or consider the fact that all of the forgoing discussion is true of Anglo-Americans and the various immigrant groups who assimilated to America-2, but less universally accurate in 2025 than it was in the whiter America of the 1980s: “wealth whispers” is not just not a thing among, say, Persians, Armenians, or Indians. Or in Dubai. And how does it all relate to America’s regional cultures?

I was also going to have a long digression about one of those “here’s what I’m making my family” cooking TikTok videos that periodically make Twitter convulse with rage, but I couldn’t find it again.9 The woman in the video was fat, her kitchen was dated and cluttered, and the cheese she was dumping into her family’s dinner was pre-shredded in a store-brand plastic bag, all of which immediately codes prole, so of course everyone was furious about how unhealthy and awful her meal was. And often the meals in this genre are genuinely dreadful, but this one stuck out to me because the recipe itself was totally fine: pasta, sausage, some kind of creamy dairy something, cheese, bake at 350. With a little something green (spinach, maybe?) it could easily have appeared in the New York Times cooking section. And if she had been visibly higher-class — if her stove and pans had been nicer, or her cheese in a bowl on a tidy counter, and especially if she had looked different — the reaction would have been very different.

But let us paralipsize all that. Fussell closes his book with an appendix that scores your class based on your home decor — hardwood floor, add four points; any work of art depicting cowboys, subtract three; each bookcase full of books, add seven — and I had ambitions to compose my own scale, but I ran out of time. (Each piece of unironic word art: minus five. But what do we do with the American flag? It generally detracts from class signaling, but rich and classy coastal New England is festooned with them in the summers, flying over porches swathed in hydrangeas.)

All kidding aside, though, the best way to know where you fall in America’s class system is to pay attention to which part of Fussell’s book make you feel uncomfortably seen. When you cringe and say, “Oh gosh, how did he know?!” that’s when you’ve found your your people.

An interesting fact related to this is that whenever Americans talk about Class N, they are actually talking about Class N-1. Things that most people describe as “middle class” are actually prole, things people think are “upper-middle class” are actually middle class, and things people call “upper class” are just upper-middle class. This is probably because nobody knows anybody in the real upper class.

Artificial rather than natural, check. Convenient rather than fussy, check. No old world associations whatsoever. The only thing preventing the gas firepit from falling into outright prole territory is the lack of word art.

The Times Literary Supplement used to work here too, but has lost prestige since Murdoch took it over. Likewise, the Paris Review has declined in quality since it stopped being a front for the CIA.

I discovered, while searching for that link, that I’ve been wrongly attributing this insight to Andreessen my whole life when it was actually Scott Adams who first popularized it!

Okay, fine, it’s sort of true, because as a mere glimpse — the lining of a trenchcoat, perhaps, which is only visible for brief moments when you move — Burberry check can still be classy. As a bold all-over print, however, it’s chavtastic: loud, brash, branded, and quintessentially prole. Still, I’m not sure how long that liminal state can last; a quick Google informs me that Queen Camilla was photographed in a Burberry trench lined with the iconic pattern five years ago, but she is (let us put this frankly) old. The Princess of Wales, much less tied to what people wore a generation ago, does wear Burberry, but not that Burberry.

Seriously, just watch this movie.

There is a kind of insistent prole-ness in the face of the uppers that blends into category X at the margin, but that’s a very fine line to draw. To do it right, one has to transcend truculence and resentment; it has be an actual disregard for judgment rather than a failure to recognize it being levied. As soon as you start saying “the elites hate that I…” you reveal yourself to be a prole after all.

Note how the one sailboat in that video is also the one boat not festooned with MAGA flags and American flags.

I first read this book years and years ago as the son of a downwardly mobile family attending an upper-prole college. And as John warns, it fundamentally changed the way I understood everyone around me and made me hyperaware of my own tastes and behaviors. Somehow, I zig-zagged my way up the ladder a bit enough to encounter, and work among, the real upper and upper-middle class of my midsized city. I had grown up in the same city as these people but had never encountered them at all before. They have done an incredible job of isolating themselves from both the mids and the proles despite their geographic proximity.

What I find particularly interesting now are the class distinctions between the strivers and the inter-generationally wealthy, both of whom I encounter in law practice. The old money people (OMPs) erect these invisible barriers that the stivers have difficulty perceiving. The strivers lean hard into the value of education and intellectual pursuits while the OMPs are almost anti-intellectual. The OMPs often have done very well academically, but it is assumed that of course you’d do whatever needed to be done to maintain your class standing. One shouldn’t lean on it too much. That’s tacky. If you admit to an OMP that you are reading St. Augustine or studying Greek in your free time, they will smirk. Acceptable leisure activities for them generally involve socializing at the club, playing golf or tennis, or spending time at your lake house. Why would you read a book? Basically, any expression of genuine excitement or earnest curiosity is right out. Everything hast to be held a little at arm’s length. The strivers like to travel to Europe and will pack their days with sightseeing. The OMPs travel to Europe, too, but they do little sightseeing. A more appealing vacation for an OMP might be skiing. They love skiing. And it’s kind of understandable why: you have to do it regularly, it costs a lot, you have to know where to go and when to go, and there’s a lot of unusual equipment and clothing involved. It's perfectly frivolous. It’s very difficult for strivers to break into this world if you didn’t grow up in it—especially if you all live in the South. While the strivers like to attend the symphony or the ballet, the OMPs sit on the board but leave halfway through the performance. And in law practice, while the strivers do most of the work, the OMPs have all the clients.

Fussell should be humiliated by proposing "Class X", which is clearly the (self-defeating) upper-middle attempt to ascend into the upper by demonstrating superior sophistication via tasteful subversion of good taste. Class X is not some escape, it is just the same old engine that keeps the thing turning (which is why it diffused down to the middle class over the next generation or so).

Conscious subversion of class expectation is the core goal of (failing) upper middle status climbers. Why? Because actual indifference to class expectation is the fundamental class marker of the upper class, and the climbing upper middles are ineptly aping it.

True ascent to the upper requires actually not caring, which is why the upper class is so hard to enter: it must be stumbled into indifferently like some magic door only found by those who do not seek it. Being third+ generation rich unsurprisingly makes this easier.