BRIEFLY NOTED: Summer Reading

My output this summer was small measured in number of posts, but large measured in number of words. Most of it went into two monster book reviews, each a story of war, government, and complicated personalities: one ancient, and one modern. But those were far from the only books I read this summer! Here are shorter takes about a few of the others.

The Qualified Sales Leader: Proven Lessons From a Five-Time CRO, John McMahon (Self-published, 2021).

It’s interesting to consider which professions obsess over “lineages.” For instance an academic philosopher and a Brazilian Ju-Jitsu fighter may not have much in common, but they can both tell you not just who their teacher/mentor was, but who that guy’s teacher/mentor was, and so on, sometimes going back centuries.1 This is not true in most fields, but you may be surprised to learn that it is true in B2B enterprise software sales. Talk to a successful sales guy, and he will find a way to slip into the conversation that he came up under so-and-so, and that so-and-so worked for the legendary Mark Cranney (Ben Horowitz’s head of sales). But talk to enough of them, and you will start to notice that a huge proportion of their lineages all converge back on a single guy named John McMahon.

You may never have heard of John McMahon, but he’s one of the most influential people alive today (there are many such people, because the world is fractally interesting). American economic growth is increasingly dominated by a handful of companies that sell software subscriptions at eye-watering margins to other large companies, and most such companies are run by John McMahon’s disciples. All enterprise software sellers today speak a common vocabulary, and that vocabulary was invented by John McMahon. Enterprise software sellers, like all professions, have weird feuds and religious disputes about what exactly the letters in various acronyms should stand for, but the acronyms were invented by John McMahon. The rival factions and schools in enterprise software sales mostly argue about the correct way to interpret John McMahon’s thought, because he is the great teacher and systematizer who laid down the laws of their world.

The reason certain fields care about lineages is that they are dominated by process knowledge that cannot be written down, so the best signal of quality is not some credential, but rather which master you trained under. Imagine how silly it would be to think that you could read a book about martial arts, and then you would know as much as the person who had written it. Some things can only be learned through grueling practice, preferably grueling practice under the observation of somebody who notices all the tiny little indescribable things you get wrong, and shows you how to do them right instead. For my favorite allegory on this topic, go to this post and Ctrl+F “wheelwright pian”.

Selling software (really, selling anything) is another such activity. And while John McMahon is the guy who has done the most to change it from an art into a science, he is acutely aware that nothing he writes down in a book can help you unless you already understand the thing that he is trying to say. So like all good religious teachers, he speaks mostly in koans and riddles and parables. It worked for the Zen masters, it worked for Nietzsche, it worked for Jesus Christ, so why wouldn’t it work for John McMahon? The whole book is an extended allegory in which John McMahon is called in to advise a failing software sales team, notices the defects in their technique, and says or does something, at which point they are enlightened. No really, all of these stories are structurally identical to the koan of Gutei’s finger:

Gutei raised his finger whenever he was asked a question about Zen. A boy attendant began to imitate him in this way. When a visitor asked the boy what his master had preached about, the boy raised his finger. Gutei heard about the boy's mischief, seized him and cut off his finger with a knife. As the boy screamed and ran out of the room, Gutei called to him. When the boy turned his head to Gutei, Gutei raised up his own finger. In that instant the boy was enlightened.

Further enhancing the book’s surreal and dreamlike qualities are the fact that it is entirely written in the first person, and includes countless seemingly irrelevant asides like: “I knocked back my styrofoam cup of stale Acela coffee and slapped Andy on the shoulder.” John McMahon is constantly invading the personal space of these imaginary people — poking them in the chest, or clapping them on the shoulders or pointing at them and saying: “Exactly.” His capitalization choices are bewildering, until the realization dawns that he is capitalizing terms that he, John McMahon, has coined. Here is a sample of the prose:

There is urgency for the customer to buy now. Urgency was formulated in Scoping through the implication of pain. You created additional urgency to implement the solution within a specific timeframe during your meeting with the Economic Buyer, and timeframes in your Implementation Plan…

“We also anchored our price to the cost justification,” Jim said. “The Champion verified the numbers, and the Economic Buyer confirmed approval to move forward based on our justification. There is verified strength in our pricing.”

“Exactly,” I said. “The customer’s value realization is in your Business Case. Stay grounded in the tangible business value of your solution.”

John McMahon is expounding a technique, a process, a science of selling that starts with the discovery of a concrete pain that the prospect is experiencing and ends with a signed deal. Each of the steps is simple and obvious, but that’s his whole point. Fields dominated by process knowledge tend to be fields that take five minutes to learn and a lifetime to master. He repeats over and over again that there is no magic shortcut, there is no golden key, there is only perfection of the basic techniques, perfection won through endless practice. His bumbling imaginary people use his vocabulary and follow his sales methodology, but they do it wrong, they know the words but they fail to grasp their true meaning. Some of them eventually are enlightened, at which point John McMahon points his finger at them and says: “Exactly.”

He doesn’t just talk about sales. There are some very good reflections on leadership in a chapter titled “Caring is competence.” John McMahon’s lip curls in disgust as he describes a company that tries to show that it cares for its employees by having group hugs. No, he says, you show that you care for people by making them great and by making yourself great and by leading them to victory. Read this, and marvel at how similar it is to Cambyses’ advice to Cyrus:

Pride is what people really want.

They want to be proud of the job they do. Proud of their increasing competence. Proud of the people they work with. Proud of the product they sell and proud of their company.

The only way to achieve an environment of pride starts with the leader doing whatever possible to help people win.

Pride is what people want.

Winning is the precursor to pride.

Competence is the precursor to winning.

Caring means making people competent.

I read this book right after Jane and I read Paul Fussell’s Class, so I could not help notice that most of the imaginary people John McMahon is pointing his finger at come from high prole backgrounds. This makes sense — sales is a field that demands a lot of aggression and agency, which the middle classes generally lack. But John McMahon himself is selling a very middle-class “power of positive thinking,” self-improvement view of the world. At the end of the book, subtext becomes text. One of the sales managers whom John McMahon has enlightened finally moves out of Boston’s working-class Irish neighborhood of Southie and into a nice house in the suburbs. And then, with a start, you realize that this entire book has been an example of the John McMahon sales methodology on the meta level. He started by discovering your pain, he created urgency, he gave you a vision of a better world, he made a business case, and now he has closed the deal.

“Exactly.”

p-adic Numbers: An Introduction, Fernando Q. Gouvêa (Springer, 1997).

The p-adic numbers are strange beasts, and the easiest way I can think of explaining them is sort of roundabout. Let’s take a normal, finite number: could be an integer, a fraction, a non-repeating decimal, whatever. What is its size? How do we define its “bigness”? No, don’t look at me like that, it isn’t a trick question. We generally think of its size as just being the number itself. Like the number 3 is “3 big.” Unless, y’know, it’s negative. In that case, it intuitively feels, at least to me, like a number is “bigger” if it’s more negative. So we can define its bigness as how negative it is, and declare that -5.67 is “5.67 big.” Now if you remember grade school, the phrase “absolute value” might be popping into your head. You may even recall your 7th grade teacher defining the absolute value as “distance from zero,” which is a nice geometric way to think about it, and even nicer since it still works when you move to the complex plane.

Is that the only way to define the bigness of a number?

Mathematicians love questions like that. Take a familiar concept, relax one of its assumptions, and then torture it until it squeals. You may end up discovering the true essence of your friendly old concept, or you may discover a new plane of reality populated by strange beings. So is it possible to have an alternative notion of size? To answer that, we have to answer a stranger question: “What even is a size?” It would take me too long to explain why this is the answer, but generally mathematicians say something counts as a size if it meets three rules:

(1) The size of the number 0 is 0, and no other number has size 0.

(2) If you multiply two numbers together, the size of their product is the product of their sizes.

(3) If you add them together, the size of their sum is less than or equal to the sum of their sizes.

Take a moment to think about how the familiar old absolute value follows these rules. Make sure you toss in some weird examples, like zeroes and negative numbers. That’s the only way to stress test a definition! It works? Great, that’s comforting. But is there any other concept of size that would work?

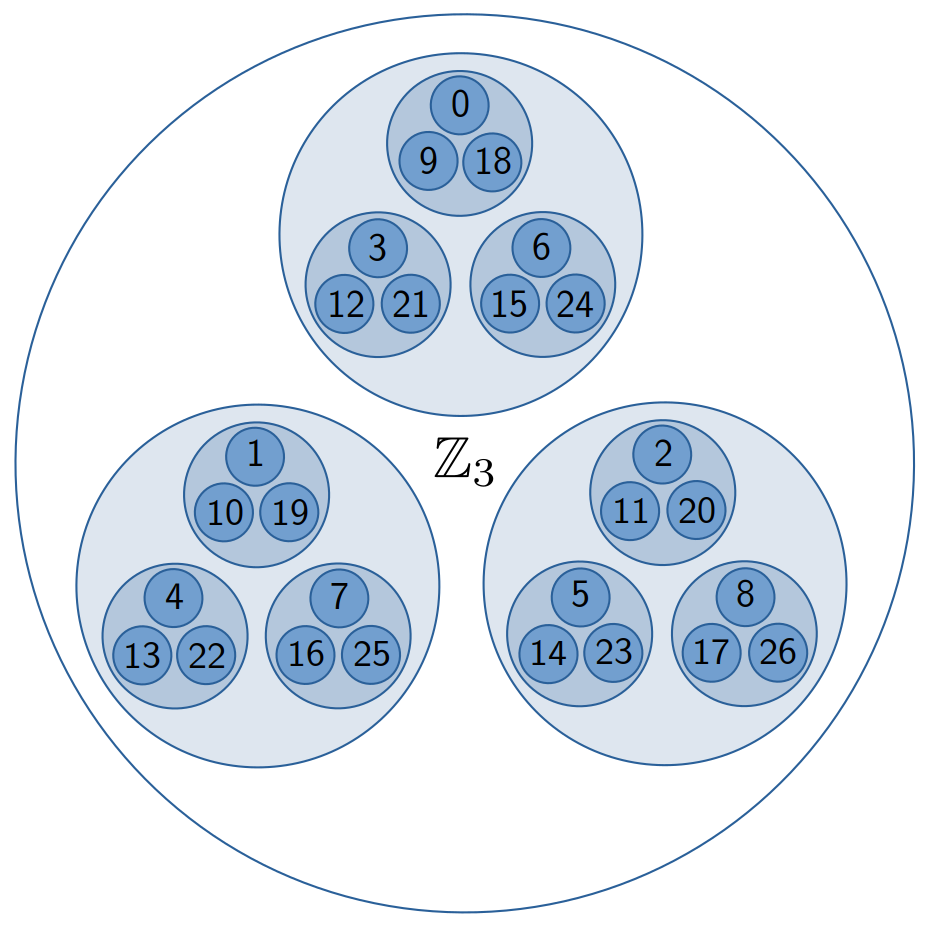

Here’s a dumb one: we could declare that the size of 0 is 0, and that the size of every other number is 1. Check it against our three rules, it totally works. But it’s boring. Here’s a zanier one: pick a prime number, p. Now declare by fiat that the “size” of a number is the highest power of p that cleanly divides that number. So for example if p were 3, then the “size” of 18 is 2, because 18 is divisible by 9, which is 3 squared, but it is not divisible by 27, which is 3 cubed. This doesn’t quite follow our three rules, because for instance the size of a product is the sum of the sizes (just because of how exponents work). But we can paper over that by throwing some logarithms into our definition in various places. We can also extend this to fractions in a sensible way, and the result is a new definition of “size,” or rather an infinite array of such definitions, one for each prime. It turns out that when it comes to the familiar numbers these are the only other possible ways to define “size” besides the usual one and the dumb one.

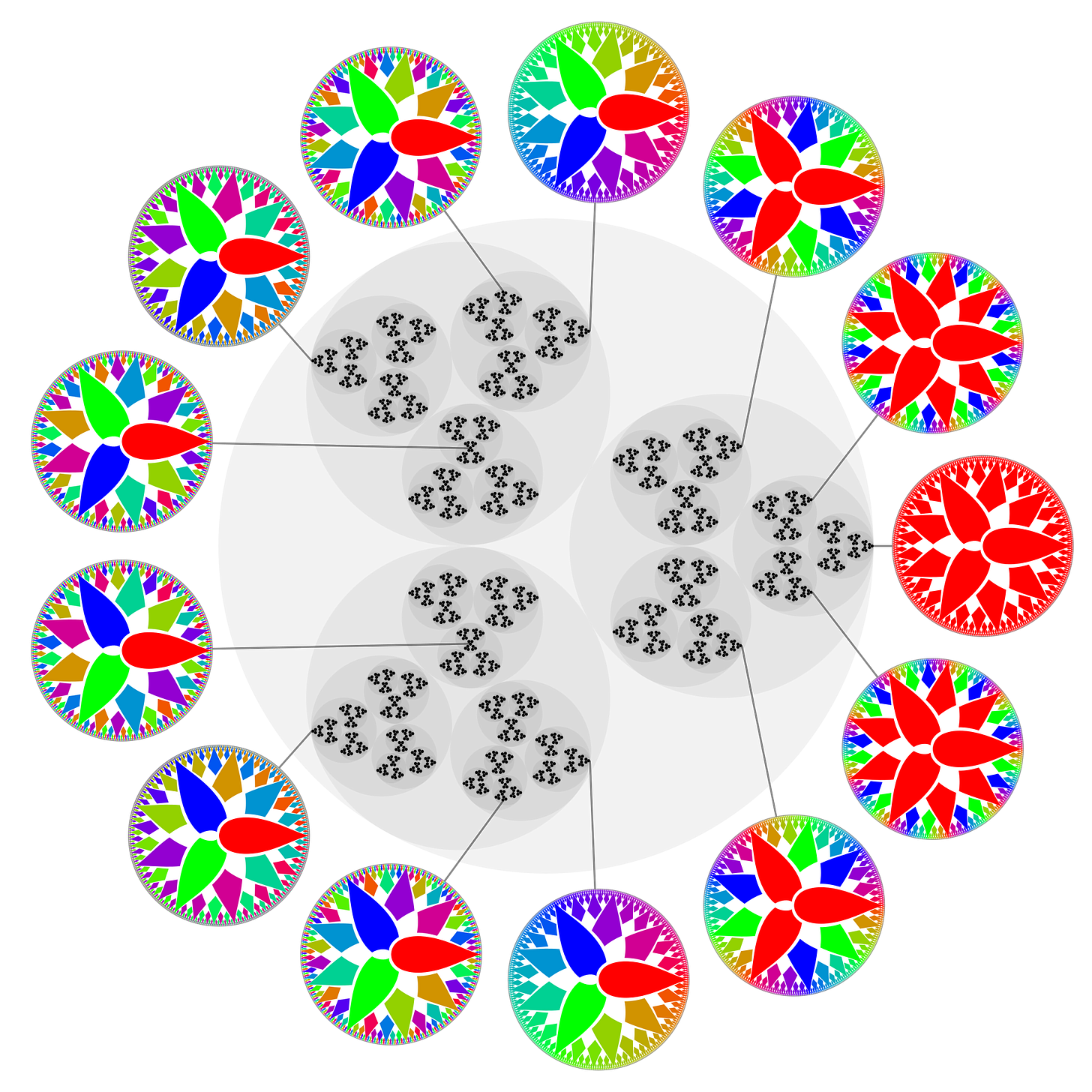

So far so good? Once you have a notion of “size,” you can move on to the idea of “distance.” Just define the “distance” between two numbers as the “size” of their difference.2 That totally works with the size you know and love, but when you pull out one of these other sizes, things get pretty weird. In our wacky new world, numbers are closer together if they are separated by higher powers of p, so 1 and 10 are closer than 1 and 4. If we now act like demented topologists and try to visualize this as an actual space, it’s a disturbing and confusing one where, for instance, all triangles are isoceles. My own way of visualizing this is that we’ve ripped the numbers out of their usual locations and placed them in a vast tree, like the tree of life or a family tree, organized by powers of p, and the “distances” in this tree are measured how many levels of branches you need to traverse to get from one number to another.

Basically, you get the p-adics by taking this vast tree, and “filling in” all the gaps where the irrational numbers would have been. We can go much, much further. But at this point, my powers of visualization fail me, and I have to start scratching this out on paper with symbols, shuffling them around in accordance with truth-preserving logical rules like some peon. My nose is buried in the symbols, and I am clinging to them like a man in stormy seas clings to a bit of flotsam. I play with the symbols, but not their referents. I see them, but I don’t really see them, because I don’t see through them to the thing that they stand for. I am not used to this experience when I am doing math. I think it’s happening because I’m getting old.

Gouvêa is not helping this feeling, because he has written this book in exactly the spirit with which I wish I could read it. He’s breezy and informal, like your cool uncle. “Let’s not get hung up on technicalities, maaaaaan, just relax and ponder the sublimely infinite forest of numbers.” He does the thing I love where he introduces the subject through the twists and turns of its history. He literally has a chapter called “Fun With Your New Head.” This is a book meant to be candy for a mathematician, a fun romp that whets your appetite and makes you hungry for a harder book so you can really dig in. But it all turns to ash in my mouth, because I can’t see the vista he’s painting for more than an occasional glimpse. It’s there, and then it’s gone again, the fog rolls in, and my head hurts. I’m getting old.

Is this what it was always like for my classmates who didn’t love math? If so I would like to formally apologize to all of you for getting impatient when you couldn’t just see the answer. When you look right through the symbols to the things they represent, you grasp things all at once. When you shuffle the symbols around you can still get there, but slowly… painfully… You’re fording a river by leaping from rock to slippery rock, instead of by flying. And when you’re at ground level, sometimes you can’t see your destination, and then you run the risk of getting turned around and all your painful, halting progress heading in the wrong direction. Douglas Hofstadter once described hitting an abstraction ceiling, but this is less abstract than things I’ve successfully learned in the past. I’m getting old.

I’m not even mad, I’m just sad. G.H. Hardy has a famous quotation about mathematics being a young man’s game, but I didn’t think it applied to me because I’m not a mathematician, just a guy who reads math textbooks for fun. It’s not like I’m trying to prove Goldbach’s conjecture or something, I have zero ambitions of producing an original contribution to mankind’s store of knowledge. I thought the rule about very few people doing good math after fifty was about creating new math, I didn’t think it applied to people who just want to enjoy it like literature. Also I’m not yet fifty. But I’m getting old.

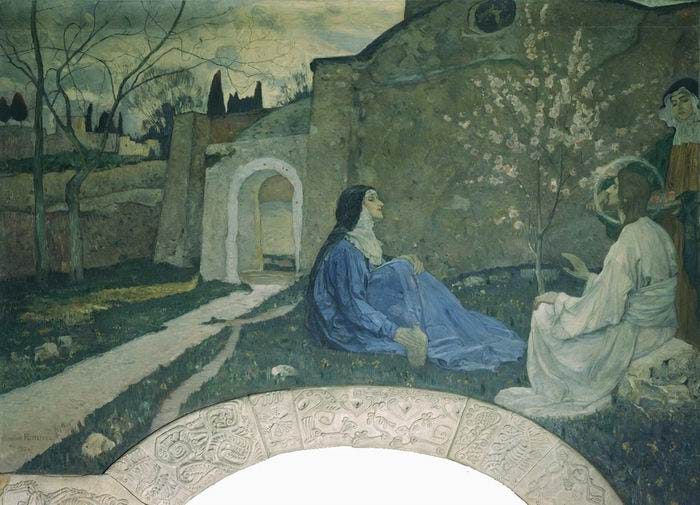

Can We Trust the Gospels?, Peter Williams (Crossway, 2018).

The Haskell programming language has the inspiring motto, “Avoid success at all costs.” That is also my motto when it comes to this Substack, but despite reviewing some incredibly niche books over the years, people unfortunately keep subscribing. In desperation I reviewed math textbooks, but it wasn’t enough. I got closer to driving you all away with my review of Ross Douthat’s Believe, but that still didn’t quite do the trick. Let’s see if this one can complete the job.

A philosophy professor friend of mine once told me how his undergraduates got “one-shotted by Neoplatonism.” He had an introductory course full of freshmen, and decided to see what would happen if he tried to convince them that Plotinus and Iamblichus were right about everything. To his shock, they all totally caved, and whatever their backgrounds by the end of it they were firm believers in the Emanations. His theory about this was simple: they were an immunologically naive population. Neoplatonism was one of the most powerful memes around for centuries and centuries, and had duked it out with countless other philosophies. But by the time his students came around, it had been dead for millennia. So the ideologies they were raised with did not provide them with antibodies against Neoplatonist arguments, and it swept through them like smallpox through the Indians.

I think something like this explains the strange revival of Christianity in some of the elite corners of the Anglosphere. The waves of disenchantment that started in the 18th century (or, if you want to be really based, in the 15th century) had finally swamped society to the point that many of us were raised in almost total ignorance of Christian arguments. So when we encountered those arguments for the first time, they felt exciting, fresh, exotic even. Chesterton once said that in order to really feel the power of Christianity, we have to step outside ourselves and look at it as the pagans did. But those of my generation and social background didn’t even need to step outside ourselves to do that.

For those of us raised with no religion or close to it, there’s a lot of remedial work to be done after we convert. When you’re raised in a miasma of secularist assumptions about the universe, some of them stick around subconsciously even after you take the plunge. For me, one of these was Biblical source criticism. If you were raised in the modern West, and haven’t ever thought much about the topic, you probably have a background belief that the Gospels are not reliable historical sources and were assembled centuries after the life of Christ by pious scribes far removed from the events they describe. You believe this because in the 19th century there was a lot of very low-quality scholarship by people with an axe to grind, and people haven’t yet gotten the memo that it was all incorrect. Fortunately, Peter Williams is here to solve your problem.

Like the Gospels themselves, Williams’ book is simple, short, and direct. It makes its case in plain and unadorned language. He is not here to bowl you over with rhetoric, but to make the reality so obvious that even a child could recognize it. Take the issue of geography: the ancient Mediterranean was not full of atlases or travel guides, and yet the Gospels teem with geographic detail. They name villages, and lakes, and particular roads, and include travel directions and durations in their account — and these details are all, invariably, correct. Sometimes the places they describe were obliterated just a few decades later, but have been rediscovered by archeological investigation, which causes a real problem for the theory that somebody wrote them long after the fact.

What if they were written much later based on stories that had been circulating for a while? This is a favorite move of those who want to deny the divinity of Christ — just say that he was a great teacher, and the stories about him got more and more exaggerated over time until they were finally written down in their current form sometime after Constantine made it the state religion. But are we really to believe that the core point of the stories got totally corrupted in transmission, while all these hundreds and thousands of irrelevant geographic details made it through unscathed? That’s not how it usually works! Moreover, Christianity spread outlandishly quickly in the early centuries, across vast distances without modern telecommunications, and with no central authority trying to keep it all consistent. But it did stay consistent — the stories were the same in Spain and in Egypt, and in Southern India, and in Arabia. Consistent down to the minor geographic details of a place that none of the hearers had ever been. This historical reality only makes sense if the things that were spreading were not stories, but texts.

This is the part where the avid reader of the New Yorker gets a very superior smirk and says, “Ahhh…but which Gospels?” Yes, a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, and Elaine Pagels has a lot to answer for. It’s true that there are apocryphal gospels, attributed to St. Thomas, or to St. Phillip (Dan Brown really likes that one), or even to Judas. But it is also true that from the earliest centuries of recorded Christian scholarship, nobody took these very seriously as eyewitness accounts and… oh, would you look at that! They don’t contain any geographic details. The “Gospel of Thomas” mentions Judaea once and no other locations. The “Gospel of Judas” literally mentions zero place names. The “Gospel of Phillip” mentions Jerusalem, Nazareth, and the river Jordan, and that’s it. It’s almost like these fake gospels are actually the thing that people accuse the real ones of being: texts written centuries after the fact by people with no real familiarity with the events that happened.

The geographic details are just one tiny example of Williams’ method. The man is very learned (not that you would be able to tell that from his simple and humble writing style), which means you get occasional treats like this note:

Earlier Hebrew had a longer and shorter form of the imperative of some verbs in the masculine singular. Hoshia is the longer form, and hosha the shorter form. The final nna is made up of a separate particle na preceded by a reinforcing n. Over time, the longer form of the imperative was entirely dropped. See also the short form hoshana, used in a sense quite different from the original in a fourth-century quotation in the Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 37b.

That’s part of an extended discussion of the word “hosanna,” which is a very old and common Hebrew word, but which appears in the Gospels with an unusual spelling that was only commonplace during — you guessed it! — the first century A.D. The book is full of nuggets like this, none of them a slamdunk case in itself, but all of them adding up to a preponderance of evidence pointing in one direction. And by far my favorite of them is the names.

Let’s suppose that the Gospels really are a historical account of real people and events, and not some later invention. Well the Gospels are full of named individuals, so we should expect the statistical distribution of their names to match that of the society from which they were taken. Sure enough, the fit is very good: if you go and tabulate the names found in first century Judaean ossuaries, the most popular ones by far are Simon and Joseph, and there are 8 distinct Simons and 6 different Josephs mentioned in the New Testament. The most popular female name at the time was Miriam (Mary). None of this is something that somebody making up a story centuries later would have known, and once again we find that the various apocryphal and gnostic gospels are full of weird names and names that were popular in other times and places.

Because you see, the thing about names is they wax and wane in popularity very fast! The most popular names in first century Judaea were not the most popular names in third century Judaea. They weren’t even the most popular names in first century Alexandria! Most of the wealthy and assimilated Jews of the later Roman Empire, the ones that somebody trying to fake the Gospels would have known, were Alexandrine. But the name distribution in the New Testament fits the name rankings of cosmopolitan Alexandria very poorly (common Jewish names in Alexandria included Sabbatius and Dositheus), and that of backward and isolated Palestine very well.

You can push the onomastics angle even further. Imagine that you have ten friends named Simon and one friend named Thaddeus. When you’re writing to somebody about Thaddeus, you might just call him Thaddeus, and when you’re writing about one of the Simons, you’d include extra information to disambiguate him. Every bit of the Gospels, down to the random side conversations, fits this principle perfectly. Here’s the list of disciples given in Matthew’s Gospel, with a number in brackets after each one designating the rank of that name among Palestinian Jews, and the disambiguating phrases in bold:

The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon [1], who is called Peter, and Andrew [>99] his brother; James [11] the son of Zebedee, and John [5] his brother; Philip [61] and Bartholomew [50]; Thomas [>99] and Matthew [9] the tax collector; James [11] the son of Alphaeus, and Thaddaeus [39]; Simon [1] the Zealot, and Judas [4] Iscariot, who betrayed him. (Matthew 10:2-4)

Note how the common names (Simon, James, Matthew, Judas) are disambiguated in some fashion, while the unusual names (Andrew, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas) are not, presumably because people knew who they were talking about. Or as Williams puts it, “not only are the names authentically Palestinian, but the disambiguation patterns are such as would be necessary in Palestine, but not elsewhere.” The crazier thing is that this pattern also happens in speech, that is in quoted statements or recorded conversations within the Gospels. It seems unlikely that somebody making up those conversations centuries later would take care to have their characters specifically disambiguate the names that were most common back then, and not the others.

There’s a lot more in this book besides names and places. I especially enjoyed the section on “undesigned coincidences,” where a story appearing in only one of the Gospels subtly or indirectly explains an occurrence mentioned in a different one. But perhaps we should turn to arguments against the historicity of the Gospels. What is the strongest argument that they must have been written much later? As far as I can tell, there’s only one: Jesus clearly prophecies the destruction of the Second Temple and the accompanying sack of Jerusalem, and those events happened in 70 A.D. In other words, if you start from the assumption that the Lord could not have known of future events then you are stuck with a timeline that strains credulity in every other way. There are none so blind as those who will not see.

For academics there’s a nifty website that’s like Ancestry.com for PhD advisors. I don’t know of an online resource like this for martial artists.

This isn’t the only way to define a distance (which mathematicians call a metric). If we repeat our trick and boil down the concept of “distance” to its barest fundamentals, we can find all kinds of other ways to measure it. Like the “Manhattan metric” that overlays a grid and declares that you can only walk down streets and avenues, and not cut through city blocks.

I'm not sure I follow you on when the gospels were written. You say that many people incorrectly believe it was centuries later, and note some evidence that they were likely written in the first century A.D. Which I understand. But then you say " Jesus clearly prophecies the destruction of the Second Temple and the accompanying sack of Jerusalem, and those events happened in 70 A.D. In other words, if you start from the assumption that the Lord could not have known of future events then you are stuck with a timeline that strains credulity in every other way." Which implies that all the evidence not only suggests the first century, but specifically prior to 70 A.D. But I didn't see evidence in your article about that spoke to A.D. 30-70 vs. A.D. 70-100?

For avoidance of doubt, I have no axe to grind here. I was just going along thinking "yup, the general consensus that the Gospels were written in 65-100 A.D. seems consistent with what this book is arguing" and then got confused in the last paragraph.

I’ve no wish to contradict your main argument about the Gospels’ integrity, but as a historian of culture and religion, I should note that Neoplatonism isn’t a tangential influence, and it never died out. It’s the metaphysical framework on which Christian theology is built (happy to provide sources; this is in part what I write about). The Dionysian writings adapt Proklos’ system directly, and that synthesis underlies everything from the doctrine of the celestial hierarchy to the liturgical structure still visible in Orthodoxy. And just for accuracy’s sake, Constantine legalised Christianity; Theodosius I made it the state religion in 380. These details shape how Christian thought and institutions evolved on the ground.