REVIEW: Reentry, by Eric Berger

Reentry: SpaceX, Elon Musk, and the Reusable Rockets that Launched a Second Space Age, Eric Berger (BenBella Books, 2024).

My favorite ever piece of business advice comes from a review by Charles Haywood of a book by Daymond John, the founder of FUBU. Loosely paraphrased, the advice is: “Each day, you need to do all of the things that are necessary for you to succeed.” Yes, this is tautological. That’s part of its beauty. Yes, actually figuring out what it is you need to do is left as an exercise for the reader. How could it be otherwise? But the point of this advice, the stinger if you will, is that most people don’t even attempt to follow it.

Most people will make a to-do list, do as many of the items as they can until they get tired, and then go home and go to bed. These people will never build successful companies. If you want to succeed, you need to do all of the items on your list. Some days, the list is short. Some days, the list is long. It doesn’t matter, in either case you just need to do it all, however long that takes. Then on the next day, you need to make a new list of all the things you need to do, and you need to complete every item on that list too. Repeat this process every single day of your life, or until you find a successor who is also capable of doing every item on their list, every day. If you slip up, your company will probably die. Good luck.

A concept related to doing every item on your to-do list is “not giving up.” I want you to imagine that it is a Friday afternoon, and a supplier informs you that they are not going to be able to deliver a key part that your factory needs on Monday. Most people, in most jobs, will shrug and figure they’ll sort it out after the weekend, accepting the resulting small productivity hit. But now I want you to imagine that for some reason, if the part is not received on Monday, your family will die.

Are you suddenly discovering new reserves of determination and creativity? You could call up the supplier and browbeat/scream/cajole/threaten them. You could LinkedIn stalk them, find out who their boss is, discover that their boss is acquaintances with an old college friend, and beg said friend for the boss’s contact info so you can apply leverage (I recently did this). You could spend all night calling alternative suppliers in China and seeing if any of them can send the part by airmail. You could spend all weekend redesigning your processes so the part is unnecessary. And I haven’t even gotten to all the illegal things you could do! See? If you really, really cared about your job, you could be a lot more effective at it.

Most people care an in-between amount about their job. They want to do right by their employer and they have pride in their work, but they will not do dangerous or illegal or personally risky things to be 5% better at it, and they will not stay up all night finishing their to-do list every single day. They will instead, very reasonably, take the remaining items on their to-do list and start working on them the next day. Part of what makes “founder mode” so effective is that startup founders have both a compensation structure and social permission that lets them treat every single issue that comes up at work as if their family is about to die.1

But there are startup founders, and then there’s Elon.

Before we talk about SpaceX, let’s talk about every single other private rocketry company ever. It’s easy to do, because they all failed (or are in the process of failing, or are likely to fail in the future). There’s an old joke in the rockets business: “How do you become a billionaire in the space industry?” “Easy, you start with two billion dollars…” Okay, I’m not actually going to talk about all of them, but here are some of my favorites. When I was young I was really into Masten Space Systems which pioneered vertical takeoff/vertical landing rockets, and won the NASA/Northrop Grumman lunar lander challenge. Now bankrupt. And then there was Armadillo Aerospace, founded by none other than John Carmack, a man who built a career in pushing hardware to its absolute limits. Seriously, read that link about the fast inverse square root algorithm (or watch a video explainer here).2 Carmack is built different. Didn’t matter. Bankrupt.

Okay, how about a different point of comparison? There’s that other private space company, you know, the one founded by Jeff Bezos several years before SpaceX was founded. Blue Origin has not gone bankrupt yet, because Jeff Bezos has effectively infinite money and has committed to keeping Blue Origin on the dole for as long as it takes. Sure enough, the company has slurped up billions of dollars in capital, and after 24 years in business has never actually launched an orbital rocket. It’s literally the joke about how to become a billionaire in the space industry, in real life. (“Easy, you start with $210 billion…”). Across the decades the pattern is clear: ambitious newcomers to the space industry all fail. Well…all but one.

Why is space hard? Fundamentally, it comes down to two things. The first is the tyranny of Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation. In layman’s terms, this equation just expresses the fact that adding more and more fuel to your rocket has less and less of an effect, because eventually most of your fuel is spent moving the rest of your fuel. Any computer scientist would look at the asymptotics of the rocket equation and say “yeah, that’s not going to work,” but fortunately rocket scientists are made of sterner stuff. However, we then plow into the second horrible reality, which is that if Earth were just a teensy bit denser or a teensy bit larger, it would literally be impossible to attain orbit with chemical rockets. We are right in a zone where it is barely possible, which means it’s a total nightmare.

Because getting to orbit is barely possible, the machines we build to do it need to operate at the absolute limit of performance that human engineers can attain. To eke out that performance, the machines must be fantastically complicated and expensive. Because they’re so complex, there are a huge number of things that can go wrong, and because the performance requirements are so strenuous, anything going wrong pretty much means total failure. Since even one thing going wrong is so catastrophic, every component now needs to be fantastically reliable in addition to fantastically performant, making it even more fantastically expensive. And remember, we’re operating at the outer physical limits of what chemical reactions can do. That means, generally speaking, that we’re using the most violent and unpleasant chemicals in existence.3 Merely storing and handling these chemicals is exceptionally dangerous and expensive, but we aren’t just storing them — we’re exploding them inside of the incredibly complex machinery that already has the preposterous performance and reliability requirements. Let’s just say that doesn’t make things easier.

All of this leads to a horrible Catch-22: since rockets are so complicated, expensive, and dangerous, we launch them rarely.4 But that, in turn, means that we build them rarely. When something is done rarely, it is guaranteed to remain expensive. A low flight-rate also means it’s difficult to discover the outer limits of performance and reliability, or to figure out which components should be redesigned. Conversely, when something enters mass production, it becomes possible to accumulate process knowledge, to move down learning curves, and generally to set in motion a process of everything getting cheaper and more reliable over time. But until very recently there was no such thing as a mass produced rocket. Each one was an artisanal project, made by skilled craftsmen, practically guaranteeing that they would stay expensive and unpredictable.

Which brings me back to the Haywood Algorithm for Business Success: make a list of everything you need to do, and then do all of it. It sounds like that could maybe, barely, work when you’re running yet another B2B SaaS company, or when you’re in charge of “Uber, but for fish antibiotics.” But it sounds like complete insanity, the height of hubris, perhaps even a category error to apply that advice to a rocket company. It’s all well and good to say, “We’re just going to do what we need to do and will not let anything get in our way,” but when the things that get in your way are national governments? The laws of physics? Really? What does that even look like?

It looks like SpaceX.

Eric Berger is a longtime space journalist covering the launch business, and this is actually his second book about the legendary company. The first one, Liftoff, covers the earliest days of SpaceX — starting with Elon Musk getting insulted and belittled by some Russian mobsters who refuse to sell him an old Soviet rocket, and ending with the first successful orbital flight of the Falcon 1. But building a rocket is the easy part. There are other people who have done that. If you were willing to spend a vast amount of money, even you could probably build a rocket. After all, the US government has. After all, Boeing has. And so we come to this newly released second book, which covers the far crazier, n=1 story of how the company went from launching a single rocket to utterly dominating the world of space launch,5 pioneering reusability, bringing down the cost of putting mass into orbit by entire orders of magnitude, and perhaps someday making human life multiplanetary.

What makes this book so good is that most of it is just stories of a rocket company following the Haywood Algorithm. For instance: when SpaceX is preparing to move their Falcon 9 rocket from its test stand to the launch site for the very first time, they hire “the second largest crane in Texas” to first stack the pieces of the rocket on top of each other, and then lower them onto a waiting trailer. Halfway through the operation, they realize it won’t work because of the wind and that they’ll have to assemble them on the ground. But the piece currently dangling from the crane and blowing like a sail in the wind isn’t designed to bear its own weight, so they literally can’t put it down.

The guy in charge of the operation joined the company a few weeks ago as a rocket engineer in California, and he is now watching the future of the company dangling in front of him from the second largest crane in Texas. Darkness is falling. What does he do? He does what he has to do: calls a few dozen welders to come the next morning, then stays up all night designing a custom “cradle” that the rocket can be lowered into while anxiously watching to make sure the crane doesn’t start leaking hydraulic fluid. He notes: “At Northrop [Grumann], building a custom cradle would have become its own mini-program with design reviews, taking months to build rather than hours.”

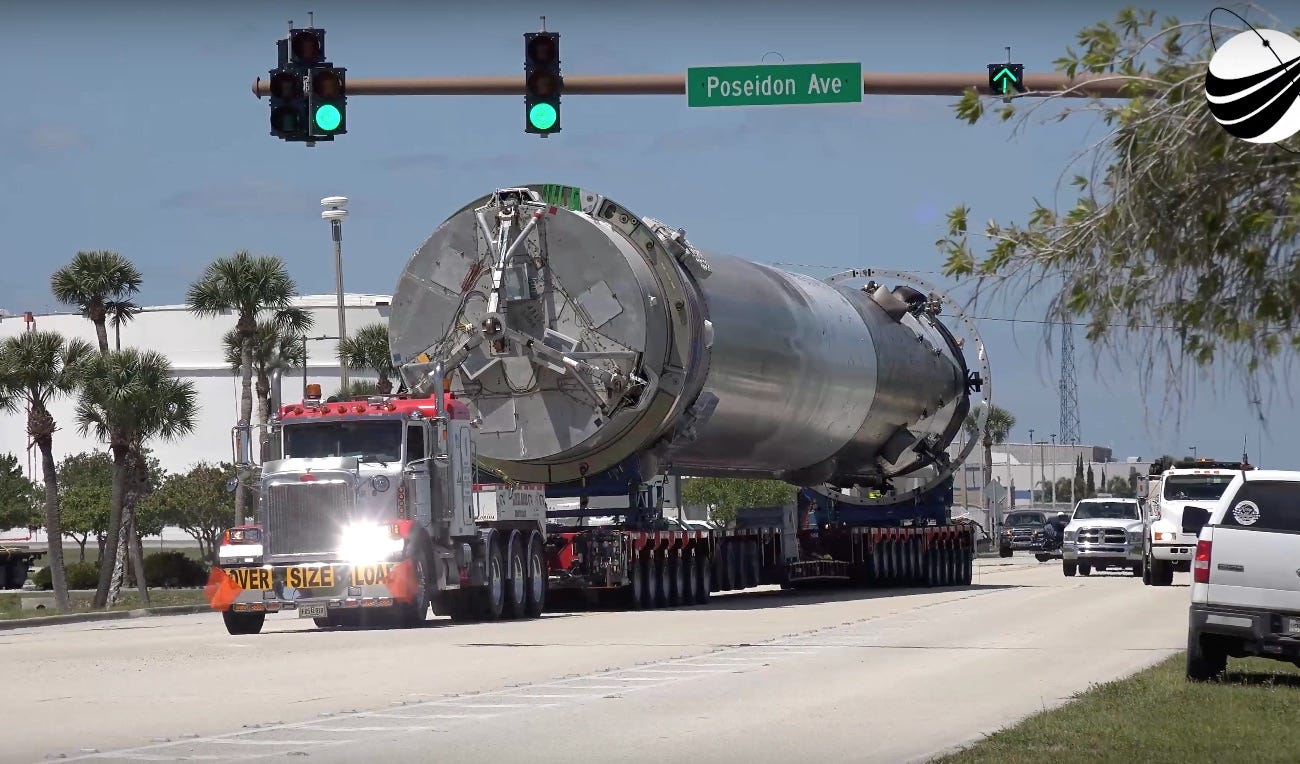

Once the rocket is down, they need to move it. To Florida. NASA and other rocket makers generally move their rockets by sea, but that’s slow and expensive. SpaceX doesn’t like to do things that are slow and expensive, so they decide to drive it there. Unfortunately, when lying down on its cradle, the rocket can’t fit under a standard freeway overpass. This is the point at which, if you did not follow the Haywood Algorithm, you would rent a barge and allow the rocket to arrive a few months late. But SpaceX always acts as if any delay at all will kill the company, so they instead set off on “the road trip from hell,” finding an absurd and tortuous route down backroads from Texas to Florida.

Their route has no overpasses, but it does have power lines and traffic lights. So some of the world’s best rocket scientists drive in front of the trailer with a flexible, 17-foot pole taped to the bumper of their car. Whenever it hits something, they jump out, use large sticks to lift the power line enough that the rocket can pass under, then jump back in their car and drive off the road and around the rocket (it’s too wide to pass) so they can intercept the next obstacle. The average speed of the trip is 10mph, and they drive continuously through the night, sleeping in shifts when they’re able to. They have a hard deadline of 5pm on November 24th, because Florida closes its roads to oversized loads for a week around Thanksgiving, and they roll into Cape Canaveral on November 24th, at 3:21pm, after ten days of continuous driving.

The launch site they arrive at is a little different from most. NASA is currently spending $3 billion on just the tower for its newest launch site. Elon Musk demands that one of his new hires (naturally) build the entire SpaceX facility — tower, ground systems, and processing hanger — for $20 million. Building a launch pad for 1% of the normal cost is a tall order even for SpaceX, but Elon is firm. He refuses to sign purchase orders for rebar, saying it’s too expensive, then he refuses to sign an order for cheaper rebar from China. Pretty soon an army of physicists and engineers is scouring Florida for scrap metal and used pressure vessels. Their greatest triumph is snagging a massive, 70-foot tall nitrogen tank used in the Apollo Program, and repurposing it to store liquid oxygen. The government will sell them the tank for $86,001 (a $3 million value!), but won’t let them use it until SpaceX can certify that it is structurally sound. So a couple of young engineers are lowered into it on winches wearing SCUBA equipment to look for cracks. The tank has since performed flawlessly for hundreds of launches.

As they geared up for the launch of that first Falcon 9 rocket, Berger tells us: “Musk wandered around asking anyone at hand — technicians, junior engineers, and company vice presidents alike — the same question: ‘What can we do to go faster?’” In some sense this entire book is just answer after answer to that question: “What can we do to go faster?” And so, when the rocket gets drenched in a thunderstorm and water intrudes into the antenna electronics, rather than replace the component they send a company vice president up into the rocket in a lift with a device resembling an overpowered hair dryer.

The craziest moment like this is when, shortly before liftoff, they discover a crack in the enormous, bell-shaped engine nozzle that protrudes from the base of the rocket. During launch, the heat and stress would cause the crack to expand, leading to the engine exploding and the rocket failing. Obviously the thing to do was replace the nozzle, but that could take months. “What can we do to go faster?” Instead they fly in their best technician from California, where he’s just come off a double shift, and have him trim off the bottom few inches of the engine nozzle with tin snips. That will reduce the overall performance of the engine, but they don’t need its max performance for this flight, and the cracked metal can’t cause a problem if it’s no longer attached to the rocket.

The only problem with this plan is that the technician is deadly afraid of flying. Well, sucks for him, because he needs to fly to Florida right now. He’s also been awake for 48 hours straight at this point. But neither of those is the heaviest cost he will bear: “Halfway into the job, Anderson noted some pain in his cutting hand. He looked down and saw that the handle of his tin snips had worn through the glove he wore, as well as his skin. He could see a dime-sized area of white bone.” What do you think he and his colleagues did? If you don’t know the answer, then you haven’t been paying attention. He wraps some duct tape around the injury and keeps cutting until the job is done.

That last story is almost too perfect a metaphor for how SpaceX reliably hires the best people on earth to do the job, and then almost as reliably grinds them into oblivion. The hours are insane. At one test facility, they rig up giant loudspeakers to blast Metallica’s For Whom The Bell Tolls early every morning to get people out of bed (oh, did I forget to mention everybody was sleeping at the office?) so they can review the previous night’s results, plan new experiments, work all day to get them set up, and inevitably work the first half of the night to accommodate some unforeseen complication, then collapse in their beds to be jolted awake by Metallica again, in an endless cycle, like some obscure area of Hell that Dante forgot to mention.6

The expectations are insane. If your work is short of perfection, you are expected to work nights and weekends until you have fixed all of the problems. You are reminded, constantly, and in no uncertain terms, that if you screw something up it may result in hardware exploding and people dying. And if you screw something up while Elon Musk happens to be looking in your general direction, there’s a good chance that you will be instantly fired.7

How do they get away with treating people like this? Well for starters, they hire a lot of very young people, especially young men. Young people do better with sleep deprivation,8 and young people are less likely to have formed inconvenient perspectives about what is and is not reasonable for your job to demand from you. But these young people aren’t exploited and treated as drones: SpaceX is one of the purest and most brutal meritocracies you’ll ever see. “Field promotions” rain from the skies, as in a military force engaged in existential warfare. Men (and women, but mostly men) in their mid-20s wind up with “Vice President” titles, or in charge of entire departments. This in turn keeps the organization hungry and ambitious, because men in their mid-20s are hungry and ambitious. They take more risks, because they have less to lose and more testosterone in their bloodstreams. This sets the tone for the whole organization.

With its hordes of young men rooming together or sleeping at the office, SpaceX can sound a little like a frathouse:

The engineers lived in hotels and motels, or in extended-stay housing and apartments, and when they weren’t working they played rock and roll at all hours of the night… it was not uncommon for the SpaceXers to get kicked out [of their favorite restaurant] when their antics approached Animal House-level rowdiness. The chaperones would introduce themselves to the manager and say that if there was a SpaceX problem to please call them, rather than the police.

“We worked like monsters,” Zach Dunn said. “But we also partied super hard.”

But it isn’t a frathouse, it’s the Indo-European kóryos warrior band, here to pillage its enemies and then feast on the proceeds. They “party like rock stars” because they are rock stars, here to disrupt the stodgiest and least disruptable industry of all time, here to go to Mars, here to “make life multi-planetary” and “extend the flame of consciousness so it won’t go out.” Hobart and Huber tell us that every startup is a little bit of a cult at times, but SpaceX truly blurs the boundary between a company and a religious movement. And this messianic quality enables it to attract not just unattached young men to the grind, but established men and women from every corner of every field, with the one commonality: they are the best of the best.

Consider, for instance, Gwynne Shotwell, who joined SpaceX as Vice President for Sales and has risen to the rank of President and COO. Shotwell is neither young nor male, and for most of her career her job has involved reassuring customers and other stakeholders whenever Elon says or does something crazy. That combination of attributes has led some people to construct a comforting mythology in which Shotwell is the “normal” and “adult” manager who secretly “runs the company” while the titular CEO is off building electric cars or arguing with people on Twitter. But this is a fundamental misunderstanding of who Shotwell is and what her goals are. It’s true that she’s one of the company’s most diplomatic leaders, and a steady hand on the tiller. But make no mistake, Gwynne is just as ambitious and visionary as Elon. In fact, the week before I wrote this review, she announced that her goals for the company included not just inter-planetary but inter-stellar travel. Government and commercial customers have successfully deluded themselves into thinking that Gwynne is the normal one, and it’s in SpaceX’s interest to encourage that delusion. But joke’s on them. There are no normal ones.

And then…there’s Elon. If you are reading this review, then like most people on Planet Earth you probably already have an opinion of Elon Musk. The most important takeaway for you from this book is that whatever your opinion currently is, it probably isn’t extreme enough. They say that when you rise high enough and your organization gets large enough, the only thing you can really still influence as a founder is the corporate culture. But Elon and SpaceX teach us that’s a huge influence indeed. Every bit of SpaceX’s highly idiosyncratic culture, everything you might consider toxic and everything you might consider admirable, all flows from one man at the top. And the purest expression of Elon’s cultural influence, the thing he has chosen to spend all his reputation capital within the company on, is: “What can we do to go faster?”

Musk would often fly to South Texas on weekends, spending Saturday night at the launch site to check on its progress and prodding where needed. On one Sunday morning, at 2 or 3 in the morning, Rench and Musk were discussing plans to build a Starship factory. Musk liked what he heard so much that he was ready to start. Right then.

“He told me to call the concrete guy,” Rench said. “He was like ‘I’m here, so he needs to be here.’ And so I called the concrete guy, the company that we used, and of course there was no answer.”

The other unusual thing for which I think Elon gets sole, individual credit is the way SpaceX has stayed nimble despite becoming a very large and successful company. Part of why startups move so fast is that they have so little to lose. If a startup is pondering some risky activity — a challenging research program, or a major product redesign, or an edgy marketing campaign, or an uncertain hiring approach — the decisionmakers know, in their heart of hearts, that the startup is default-dead anyway, so they might as well roll the dice. Big companies are vastly less likely to engage in these risky activities because doing so could destroy billions of dollars of enterprise value. The secret weapon of SpaceX is that anytime they’re tempted to fall prey to loss-aversion, and to quietly shelve some big risky plan because it threatens to derail the valuable business they’ve already built, Elon shows up and screams and threatens to fire everybody unless they do the risky thing.

Thus, despite being a large, valuable company with a very successful and profitable business, SpaceX regularly takes existential gambles that could destroy the entire company if they go wrong. By the time the Falcon 9 was up and running, SpaceX had essentially won: they could have rested on their laurels and enjoyed their monopoly for the next few decades. Instead, they bet the entire company on propellant densification (which blew up a rocket or two and indeed nearly destroyed the company).9 Then, once that was working, they bet the entire company on the Falcon Heavy rocket, whose development program nearly bankrupted the business. After that, they bet the entire company on the Starlink satellite constellation. Most recently, they have taken every bit of money and talent the company has and redirected them away from the rockets that make all their money and towards the utterly gratuitous Starship system.

Each of these bets might have been a smart one in a statistical sense, but it still requires a special kind of person to take a $200 billion market cap and bet it all on black. So why has Elon done this? Does he just not believe in the St. Petersburg paradox, like Sam Bankman-Fried claimed to do? No! It’s actually very simple: remember all that stuff about how SpaceX is less of a company and more of a religious movement, with a goal of making life multi-planetary? Elon and SpaceX behave the way that they do because they believe that stuff very sincerely. A version of SpaceX that merely became worth trillions of dollars, but never enabled the colonization of Mars, would be a disastrous failure in Elon’s eyes.

Every bit of company strategy is evaluated on the basis of whether it makes Mars more or less likely. This fully explains all the choices that look crazy from the outside. SpaceX does things that look incredibly risky to conventional business analysts because they reduce the risk of never getting to Mars, and that’s the only risk that matters. This has the nice side-benefit for shareholders that it’s revolutionized space travel several times and built several durable monopolies, but if Elon decided that actually blowing up the business increased the odds of getting to Mars, he would do it in a heartbeat. He’s said as much. This all has very important implications that we will return to in a moment.

A necessary, and to me charming, component of this approach is an utter disregard for bad press. Most corporate communications departments live in flinching terror of the slightest whiff of negative PR. Meanwhile, SpaceX’s puts out official blooper reels of exploding rockets. More seriously, one of the company’s lowest points came in the aftermath of the CRS-7 mission, when a rocket exploded two and a half minutes after launch and totally destroyed its payload. Most companies would do everything possible to minimize the risk of the following “return-to-flight” mission. SpaceX instead used it to debut a completely untested overhaul of the rocket and to attempt the first ever solid ground landing of an orbital-class booster. (It succeeded.)

Hopefully by now it’s not a mystery why SpaceX is a far more effective organization than NASA, but I think this last point is underappreciated. NASA, unfortunately, has boxed itself into a corner where it cannot publicly fail at anything.10 But if you aren’t failing, you aren’t learning, and you certainly aren’t trying to do things that are very hard. SpaceX, conversely, rapidly iterates in public and blows up rockets to deafening cheers. Permission to fail in public is one of the most powerful assets an organization has, and it flows directly from the top. This, too, is something for which Musk deserves credit.

The last thing I’ll say about Elon is that he is notably, uhhh, unafraid to disagree with people. In fact, this book literally has a chapter subheading called “Musk versus the entire human spaceflight community.”11 This quality can be a bit of a two-edged sword, but it’s safe to say that without it the company would never have gotten anywhere. Practically from the moment SpaceX came into existence, its enemies were trying to destroy it. Anybody who followed space policy in the early-to-mid 2010s knows what I’m talking about — politicians like the imbecilic NASA administrator Charles Bolden and the flamboyantly corrupt US Senator Richard Shelby did everything in their power to make life difficult for SpaceX and to smother the newborn company in its crib.

It’s a sign of how total SpaceX’s victory has been that some of those old episodes feel surreal in hindsight. Not just the antics of clowns like Bolden and crooks like Shelby, but also the honest-to-goodness competition in the form of Boeing and Lockheed, who fought dirty from the very beginning. For instance, they lobbied hard to block SpaceX from having any place to launch rockets at all, and dispatched their employees to stand around SpaceX facilities mocking and jeering while taking photographs of operations. In those early, desperate days, it would only have taken one or two successes of Boeing’s massive lobbying team to lock SpaceX completely out of government contracts and starve them of business. It was only Elon’s reputation as “a lunatic who will sue everyone” that prevented NASA from awarding the entire Commercial Crew Program to Boeing despite SpaceX offering to do it for about half as much money.12 And of course Elon actually did sue the Air Force when under intense lobbying they froze SpaceX out of the EELV program.

All of this is ancient history now. SpaceX’s competitors are no longer trying to stop the company with lawfare, because SpaceX no longer has any meaningful competition. But there are still people trying to slow down and sabotage the company; they’re just doing it for ideological rather than economic reasons. In the early days of SpaceX, the “deep state” of unelected bureaucrats who direct and control the United States government were huge supporters of the company, because back then the reigning ideology of that set was a sort of good-government technocratic progressivism and the idea of a scrappy new launch provider disrupting the incumbents genuinely pleased and excited them. A few years later, the state religion changed, and a few years after that, Musk revealed himself to be a definite heretic. And so, in utterly predictable and mechanistic fashion, the agencies that once made exceptions for SpaceX now began demanding years of delays in the Starship program in order to study the effects of sonic booms on tadpoles and so on.

One might be tempted to rage about how detrimental this all is to the rule of law. Think of the norms. Berger is certainly upset by it, and he ends his book (published in September 2024) by urging Musk to self-censor and stop antagonizing powerful forces with his political activism. Implicit to this demand is the advice, “If you just act like a good boy and stop making trouble, they’ll go back to leaving you alone.” Obviously, Musk did not take this advice. He instead further kicked the hornet’s nest by redoubling his support for Donald Trump. By October, the social network formerly known as Twitter was teeming with employees of US spy agencies and their allies demanding that SpaceX be nationalized and that Musk be deported.13 Given that Trump’s election was no sure thing, why would he take this risk?

There was a famous uprising against the Qin dynasty that happened when two generals realized that (1) they were going to be late, and (2) that the punishment for being late was death, and (3) that the punishment for treason was…also death. Elon Musk thinks being late to Mars is just as bad as being deported and having his companies taken away from him. He has already gambled the entire future of SpaceX on a coin flip five or six times, because he considers partial success and total failure to be literally equivalent. When it became clear that an FAA empowered by a Harris administration would put one roadblock after another in front of him, his only choice was to rebel and to flip the coin one more time.

When I saw Musk charging into the lion’s den back in October, I immediately thought of the Haywood Algorithm and its dreadful, stark simplicity. “Make a list of everything you need to do in order to succeed, and then do each item on your list.” When you run a normal company, the algorithm sometimes demands that you stay late at work or come in on a weekend. When you run a rocket company, the algorithm sometimes demands that you buy Twitter14 and use it to take over the United States government. It’s far from the riskiest thing Musk has done on his path to Mars. At this point, it might be wise to stop betting against him.

In a way, startup founders represent an unwinding of James Burnham’s managerial revolution — a return to the days of bourgeois proprietorship, when owning a business meant having your name on a sign outside the door.

There is dispute over whether Carmack actually invented the fast inverse square root function (Wikipedia says no), but I don’t think it actually matters because it’s the kind of thing he would invent.

Derek Lowe has a whole series on the worst chemicals in existence titled: “Things I Won’t Work With.” An alarmingly large number of them are rocket fuels. If you want a taste of the series, start here.

Or at least we did before SpaceX came along.

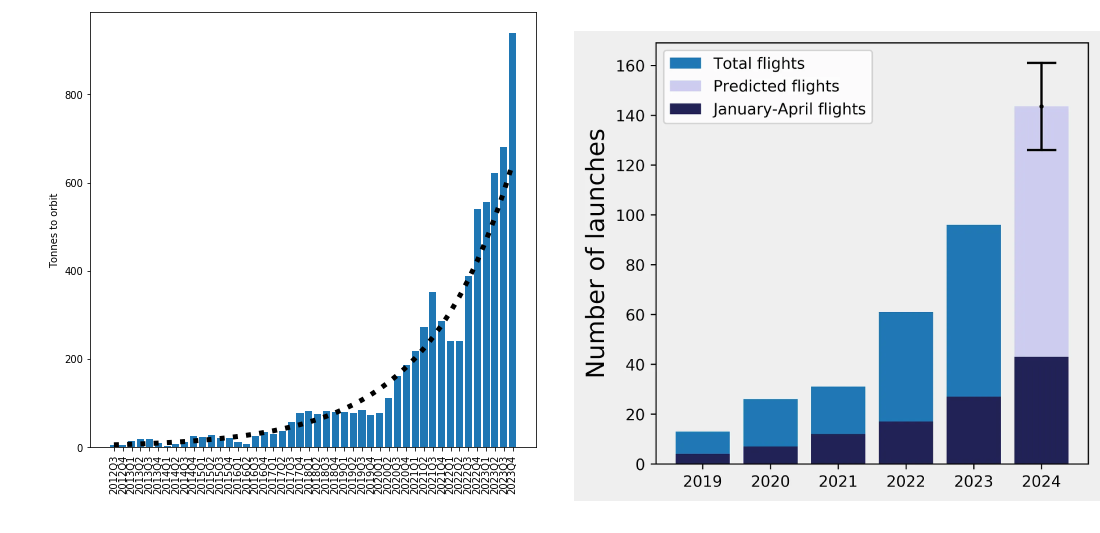

The best quantitative analysis of the SpaceX steamroller is by Peter Hague, who is also the source of the images above.

At a different facility, an employee who’s spent several months working 16-hour shifts starting at 1am each day to get a rocket ready for launch begins whooping and celebrating as it begins to leave the pad, before it’s even clear if the launch will be successful. When somebody demands to know why he's already happy, he gloats: “because that bitch ain’t ever coming back.”

One of the more amusing anecdotes in the book is one of these Musk insta-firings gone awry. Elon isn’t happy with somebody, so he calls their colleague and orders them to fire their coworker. The colleague protests that the firing is unjustified, so Elon again orders the firing, and says if they don’t do it, he’ll fire both of them. The colleague hangs up the phone, turns to the original person, and nonchalantly says that everything is fine. Elon rapidly forgets about it and never raises the issue again.

This is why young people should be having kids. Take it from somebody who’s had new babies both shortly after college and deep into middle-age — it’s a lot easier when you’re young.

“Propellant densification” may sound like a nerdy topic, but it’s actually one of the most interesting subplots in the entire book. In the interest of making the Falcon 9 the highest performing rocket ever, and especially in the interest of improving the economics of booster landing and reuse, SpaceX decided to try to just pack more fuel and oxidizer into the tanks. The way you fit more of a gas or liquid into a given volume is by making it colder. So they developed a way to chill liquid oxygen down to -340 degrees Fahrenheit, way colder than anybody had ever made it before. What they weren’t prepared for was that at these temperatures, liquid oxygen starts making all kinds of horrible, eerie noises that made the engineers not want to be around it.

Remember propellant densification? NASA considered it in the 80s and 90s, but dismissed it. Not for technical reasons, but because the need to destructively test pressure vessels might result in negative news stories.

The subject of this section is whether it’s acceptable to fuel a rocket when the astronauts are already inside. The position of “the entire human spaceflight community” was that fueling can be dangerous, so better to complete propellant loading first, wait for everything to settle, and only afterwards being the astronauts on board. Seems sensible enough, but remember propellant densification? SpaceX’s ultra-cold liquid oxygen immediately begins heating up after loading, so the only practical way to use it is to load at the last minute and then immediately launch the rocket. Densification was vital to eking out the last bit of performance margin that makes rocket reuse possible, so Musk stuck to his guns. So far zero astronauts have died as a result.

NASA’s pretext for favoring Boeing over SpaceX was the former’s “reliability” and “experience” and “technical superiority.” In the decade since then, SpaceX has completely dozens of missions flawlessly, while Boeing has yet to actually make it to the International Space Station and back.

It’s hard to tell when the radical centrists mean things “seriously but not literally,” but I sincerely think that had Trump lost the best case outcome for Musk would be something like Jack Ma: chastened, humiliated, wings clipped, freedom of action greatly reduced.

It’s become fashionable to mock Musk for running Twitter into the ground, but control over the social network’s content policies probably had a major effect on the election outcome. Even if Twitter literally becomes worth zero dollars (which given Musk’s track record I doubt), surely you can imagine how when you have a tremendous amount of money, $44 billion might seem like a small price to pay to have the President of the United States owe you some major favors.

As the relevant Charles Haywood, I approve and admire this review, totally aside from its mention of me.

Probably one of the more insightful pieces on Musk that's been written, great job