JOINT REVIEW: Family Unfriendly, by Timothy P. Carney

Family Unfriendly: How Our Culture Made Raising Kids Much Harder Than It Needs to Be, Timothy P. Carney (Harper, 2024).

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

Jane: So, we have a bunch of kids. And sometimes, usually when something pleasantly mundane is happening — the little kids are building something and the big kids are reading their books and the baby is gurgling away and I’m making dinner, perhaps, or when we’re all bustling around packing lunches and practicing spelling words and chitchatting — I look around and think to myself, “Wow, this is so great. I’m so lucky to have all these awesome people in my house. Why don’t more people do this?”

There are, of course, downsides: I am typing this very slowly because one of my arms is full of a baby who doesn’t like to nap unless I’m holding him. You have to label the leftover lasagna you’re taking for lunch tomorrow or else someone will have it for a snack. I am staring down the barrel of at least another decade of the exact same Mother’s Day musical program at the kids’ school, and it would probably be rude if I started singing along. And there are days when we’re waiting around like Kurt Russell at the end of The Thing to see where the stomach bug will strike next. But come on, nobody doesn’t have kids because of the existence of norovirus.

So…why don’t more people do this? (Either having a bunch of kids or, increasingly, just having kids period.) I’ve heard a lot of theories: just recently and off the top of my head, I’ve been told that kids cost too much money, that kids don’t actually have to cost a lot of money but we have very high standards for our parenting, that there are too many fun things you can’t do anymore when you have kids, that having a lot of kids is low status, and that being a housewife (an increasingly sensible choice the more kids you have) is low status. And, of course, car seat mandates. There’s something to most of those theories, but they all boil down to one fundamental claim: we’ve built a world where having kids, and especially having a lot of kids, just…kind of sucks.

It’s never going to be easy — there will always be sleepless nights and bickering siblings and twelve different people who all need incompatible things from you all at once — but anything worth doing is hard sometimes. It’s also often wonderful, and it doesn’t need to be this hard.

Tim Carney agrees with me, providing a guided tour of the cultural and structural factors that combine to make American parenting so overwhelming that many couples are stopping after one or two children — or opting out altogether. We think our children require our constant close attention. We worry about them incessantly. We think anything that’s not absolute top-tier achievement is failure. We build neighborhoods that mean they need to be driven everywhere, and then between car trips we all stare at our glowing rectangles. We, and they, are sad and lonely, and then no one around us has kids and we all get sadder and lonelier.

So what do you think? Why don’t more people do this? Why are we so weird?

John: I am a simple man, and prefer simple (preferably materialist) explanations. It’s effective birth control, duh.

Oh, I’m sure all the stuff Carney talks about in his book plays some role. All the economic factors and the regulatory factors and the changed social expectations and the lack of sidewalks, and the blah blah blah. But why did those things all happen, all of a sudden? It's actually very simple — now you can have sex without children necessarily resulting.

The correct way to view all the changes that Carney lists is as a sort of transmission belt that has slowly and inexorably propagated and magnified the effects of the one, very simple technological change that occurred. The story goes something like this: birth control is introduced, but large families are still normative and supported by generations of cultural accretion. So people still have an above-replacement number of kids, because they remember their mothers and grandmothers having 10 or 12 kids, and because society is still basically set up for families. But time passes, and culture gradually shifts to accommodate material reality. Law and economics follow culture. The next generation remembers their parents having 3 or 4, and maybe manages 1 or 2 themselves. The fewer people are having lots of kids, the less of a constituency there is for having lots of kids, and the harder society makes it, further turning the screws on marginal parents.

One objection from those who disdain the simple, materialist explanation is that the change didn’t happen overnight. The transmission belt theory nicely addresses this — it doesn’t happen overnight because societies have culture, and culture has inertia. Even insanely messed-up cultures that are inimical to human flourishing are hard to change. A residual, pro-childrearing cultural hangover can last for a while after the facts on the ground shift, and means people keep having babies for a little while. But it can’t last forever. Eventually it crumbles.

The other big objection to this theory, one Carney raises himself, is that if you do surveys of people, especially women, they report having fewer children than they want. So, the argument goes, it can’t just be birth control, because if it were people would have all the kids they want. But the answer to this is so obvious I’m shocked it isn’t apparent to Carney. People have high time-preference. People procrastinate. People are really bad at doing things which are hard in the short-term but make you happy in the long-term. The great thing about unprotected sex is that it connects your short-term and long-term happiness. As soon as you have the option to not have a baby right now, this time, it’s awfully tempting to say: “you know, I totally want all the diapers and spit-up eventually, but not this time, maybe next time.” In other words, people only reach the actual number of children they want via happy accidents or, in the old days, by having all thoughts of long-term consequences banished by good old-fashioned lust. This is literally why evolution made sex fun. The position of having to make an affirmative decision to have a baby is completely unnatural, and sometimes I’m amazed that anybody does it at all.

So you wind up with people like the friend I mentioned at the end of this book review (who, by the way, a year and a half later is still no closer to having a baby). Desperately wanting a child, sort of, but too neurotic or hesitant or conflicted or something to do it. In the old days, it would have been simpler, because they wouldn’t have had a choice. Biology would have made the decision for them, and a few years later they’d be happily bouncing a baby on their knee (or miserably bouncing a baby, whatever, the point is they’d have a baby). I really think that’s all there is to it. What truly blows my mind is that Carney wrote an entire book about this stuff while barely mentioning birth control (and only discussing its second-order cultural effects when he did). Presumably he had orders from his Jesuit masters to avoid the topic lest his cover be blown.

Jane: I think you’re too hard on Carney — he’s very publicly and very seriously Catholic, and if he wants his book to sell outside the Catholic publishing ghetto1 (which I assume he does, because he’d like to change some people’s minds and also feed his many children) he can’t make it too easy for people to disregard his book on the grounds that it’s crazy Catholic nonsense. Luckily, we are here to say the quiet part out loud.

Also luckily, we are not Catholic and thus are allowed to think that there are good things about the existence of effective birth control. But the thing about technology is that as soon as it lets you make a decision to do something, you have to keep deciding. I’m glad I have a smartphone, for instance: it’s nice to be able to order more toilet paper as soon as I realize we need it, I can keep in touch with friends and family all over the world, and I always have my book with me for those five minutes chunks in the grocery line or at the playground. But like everyone else, I look at it way too much; if I have time to actually read for more than five minutes, I have to pick up the physical Kindle or (better yet) a paper copy, because otherwise I’ll keep scrolling away to check Twitter.

But that’s not the end of the world except for my deteriorating attention span, and frankly my own fault. So let’s think instead of something more serious: the brutal, invasive, but potentially life-saving medical interventions available in America’s ICUs. They can do amazing things these days, and for the twenty-three-year-old car crash victim that’s an incredible gift. But because things like an ECMO exist, you suddenly need to decide whether to deploy them for the ninety-year-old with dementia or the terminal cancer patient — people who should be permitted to die without being tortured with “heroic measures” first, but whose families are now faced with an active choice no one should be asked to make.

So obviously yes: people are having fewer kids because they’re able to have fewer kids. Which is especially ironic since, heredity being what it is, those conscientious, risk-averse planners who keep choosing not to have kids would probably have the easiest-to-manage kids of all!2 Or at least they would if they let themselves, because I think Carney is exactly right that the major drivers of parental stress — and thus parental “oh goodness no I couldn’t handle another one” — are self-inflicted.

A few months ago I had what I thought was a revelation: all those people who were spending their evenings and weekends shuttling their children to sports practices and games, dance classes and riding lessons and swim meets, must really like this stuff. They must think it was fun and enjoy sharing their passion with their children! It had to be like when I garden or bake with my kids, or read them books I love, or tell them about the proto-Indo-European voice system! (Don’t laugh, it’s important context for Latin deponents.) So the next time a mom I know was complaining about getting her kids out the door for flag football practice, conveniently scheduled for (1) rush hour and (2) dinnertime, I smiled and asked, “Are you guys big football fans generally?” I was all set to inquire about their family’s favorite team, the differences between college and professional ball, how different flag football is from tackle and whether they intended to make the switch when her boys were older — but she grimaced and shook her head. No, she said, not really. They watched the Super Bowl but that was about it. “Ah,” I nodded sagely. “But the kids are into it?” (Lord knows I’ve indulged my children’s enthusiasm for things I don’t care about.) No, she said, not particularly. But they needed a sport for the fall.

I didn’t ask why. I wish I had, because I’m sincerely curious — these were busy, active kids, actually in the process of racing around the playground with their buddies while the adults chatted, so it’s not as though they needed organized sports to keep them from merging with the couch cushions — but at the time it seemed rude and pushy so I changed the subject. Now, obviously not everyone is like this mom: some people, including Tim Carney, really do love sports and delight in sharing that love. But the truth is, people are obsessed with signing their kids up for stuff. Carney calls it the Travel Team Trap, and it’s probably most evident in youth sports culture, but it shows up everywhere. Your kid likes to write? Find a creative writing class! Having fun with chess? Quick, hire a tutor! My local rec center even offers courses in Dungeons & Dragons, taught by a real live professional nerd, because apparently eating Doritos in your mom’s basement while your friends mock you for touching the Sphere of Annihilation isn’t good enough any more.

And it’s a vicious cycle, because all these official activities crowd out informal play. If the artsy kids in your neighborhood are taking a musical theater class half an hour away, there’s no one to join your kids in pulling out the dress-ups and staging a drama of their own. If everyone is off at soccer practice, you can’t meet up at the park to kick the ball around. Sorry, Zerubbabel can’t come over and play Legos this week, he’s got his STEM Makers class on Wednesday and then Thursday afternoon is junior robotics team… Soon even the families who want a more relaxed, unprogrammed life are signing their kids up for things because it’s the only way they’ll ever see their friends.

There’s nothing wrong with formal instruction in its place, especially for things where technique really matters: the world needs basketball coaches and piano teachers, too. And sometimes it’s just fun! A big stage with lights and music and real costumes scratches an itch that Mom’s old prom dress and a dinosaur mask (“Velociraptorella,” currently in previews off-off-off-Broadway) just can’t touch. But when we regard these things as potentially interesting and entertaining, rather than absolutely vital to our children’s well-being, we can make sane tradeoffs about them. A day-trip to the awesome museum in a neighboring city is also potentially interesting and entertaining, but nobody thinks you’re a bad mom if you spend the weekend doing something else.

And what’s more, the push for legible achievement over experience, without regard for what’s good for your family — or even, apparently, whether your kids like it — robs them of the opportunity to motivate and direct their own lives. Basketball practice three times a week surely does more for your jump shot than a pickup game at the local park, but in the long term the ability to take ownership of your time, make and keep plans with your friends, sort out interpersonal disagreements, etc. are going to be a lot more useful. (And, sorry, I’m still stuck on this D&D thing: the threat of your friends losing interest and wandering off to play foosball instead is a much greater incentive to become a good DM than anything you could learn in a class.)

But it’s not actually surprising that people parent like this, because it’s how they grew up: today’s moms and dads are yesterday’s Organization Kids.3 Their image of the good life is tallying up achievement points on some great celestial board. And no wonder they’re desperate to tally up points for their kids, too: they think their futures depend on it! In fact, every time I bring this up, someone tells me that Harvard is full of kids whose parents drove themselves crazy coordinating travel sports schedules and private school dropoffs and chess tutors — all of which is true, and some of which is probably even causal. (Nobody appreciates achievement points tallied up on a great celestial board like a college admissions office.) But a lot of it is also because that’s how smart, conscientious, upper-middle-class parents are expected to raise their kids, and the best way to get into Harvard is to be the offspring of smart, conscientious, upper-middle-class people. (It also helps if they’re neither white nor Asian.)

John: Sorry, I’m going to go back to heredity for a moment. Heredity is also why the people worrying about the population going to zero are silly. There are many examples out there of species undergoing environmental shocks that suddenly change which traits are adaptive and which are not. People like to say “evolution takes a really long time,” but there’s actually exactly one situation where it doesn’t, and it’s the situation we’re in. If the genes for some newly adaptive trait are already in a population, they can spread extremely quickly.

Imagine an extreme version: a new virus is unleashed, it’s completely fatal, but 1% of people are naturally immune to it. In the next generation, 100% of people will be their descendants and will have the gene in question, and they will go on to repopulate the earth. Well, birth control (and televisions, and video games, and fentanyl, and brunch, and all the other fun stuff you can do besides having kids) is kind of like that virus. It’s taking out a big slice of the population, but another big slice appears to be resistant, and the future will look more like them.

To take one example: something that the Mennonites and the Ultra-Orthodox Jews and various other high fertility subcultures have in common is they’re religious and communalistic. I suspect that before modernity, being highly religious and communalistic was actually negatively correlated with fertility (especially for men). But this giant environmental/technological shock has flipped the sign. I suspect that religiosity is at least partially genetic, and so the future will look a lot more religious than the past. There are many other traits like that, which used to mean you had fewer kids than your neighbors, and now mean you have more kids than your neighbors. The share of the population that has those traits will expand very quickly, and we'll get back to healthy population growth.4 The next century or so might be exciting though.

Anyway, that’s good news for our great-grandkids, but one way to view Carney’s book is as a list of suggestions for making things less annoying for parents today. But I can’t help feeling that a major undercurrent beneath all of his advice and policy prescriptions and so on is: “secede.” That is, become like the Amish and the Haredim, find similar people and build parallel institutions that support the form of life you want. Sometimes that’s the right call, but I think if you do want to influence the rest of society to become more like you, there’s a different time-tested approach and it’s “become high status.”

Jane: lol, good luck!

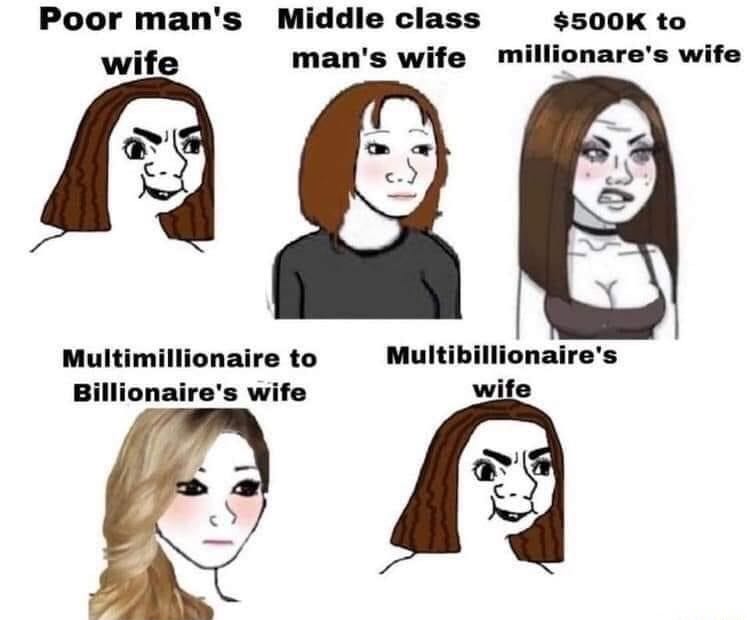

Seriously, I can think of a few examples of things that are lower-status than having a large family, but they’re all stuff like “active meth addiction.” Too many kids is up there with smoking cigarettes, having an above-ground pool, or voting for Donald Trump: trashy.

The problem isn’t quite that kids are low status, though. What’s actually low status is kids who aren’t raised to the highest possible standards — kids who don’t have their own bedroom in a good school district, fully-funded college education, regular air travel (preferably international), plenty of expensive activities, and of course their parents’ constant loving attention — kids who aren’t raised right.

I have no idea who this person is and I don’t mean to pick on him or her personally — except that introducing Zoombinis to your kids is so much fun that this particular avatar/message combination makes me sad — but this tweet sums up the mindset perfectly. And it is, to be clear, crazy. It’s like saying “gosh, I’d love to have friends but I just can’t afford to treat them to a Michelin star restaurant once a week, so I’ll sit here in my house all by myself instead” while normal people are hanging out on the porch with some beer. And while this attitude may encourage people to opt out altogether, it encourages even more to keep their families small. If you can’t meet any of those expectations, fine, you’re probably not at risk of being high status anyway, but there are a lot of people who can manage some, or even all, of that — for one or two kids. So that’s where you’re supposed to stop, because otherwise your children aren’t getting what they need.

Now, of course it’s important to raise your kids right. In fact, it’s one of the most important things you can do. Children are an awesome gift and a staggering responsibility, and our standards should be very high — for things like loving them, providing them a peaceful and stable home, guiding their character, and teaching them what it means to be a person. (They should also be high for things like “enjoying the eighteen-ish years you get to spend living with them.”)5 And yes, having children definitely means spending money you wouldn’t otherwise spend: they take up space, they eat food, they need clothes, and you probably want to give them fun stuff like bikes and books and Legos. (Also they sometimes break things. I’m told.) But none of that has to be enormously expensive, and a life with college loans is still worth living.

The real crunch, the reason large families are still low status even if they’re rich enough to fly everyone to Lake Como for spring break, is the limited supply of parental time and energy. Raising kids “right” is supposed to mean devoting every waking moment to them, and you simply can’t intensively parent a whole houseful of kids the way you do one. You can’t hover over little Ashurnasirpal in the sandbox narrating his play at the same time as you stage-direct wee Sophonisba’s ascent of the jungle gym, and you certainly can’t do that while you also monitor the swings to make sure young Tiglath-Pileser isn’t going dangerously high. And you know what? Good.

Carney describes what he jokingly calls “detachment parenting”: once your kids hit the developmental level to handle it — beginning around eighteen months or so, depending on the kid, and definitely by three — sometimes you need to just let them be. Let them figure out what to play and go, I don’t know, read a book or something. Do the crossword. Call a friend. Cook dinner. Start a Substack! (Or deal with the baby your relaxed approach made you feel like you could handle.) This is good, sensible parenting — but let’s not pretend it’s high status behavior. Nobody is looking at the lady sitting on the park bench with a book while her kids frolic and thinking, “Wow, what a great mom.” The hovering, the narrating (“Oh look, an excavator! Can we make an excavator noise? Vroom vroom!”), the constant accompaniment of children plenty old enough to go out on their own, are all performative: look what a good parent I am! Look how engaged! Yes, some people do this because of untreated anxiety disorders, but most people do it because it’s what you’re supposed to do. It’s what high status parenting looks like.6

Now, I happen to think this kind of constant engagement and supervision isn’t actually good for kids, who should be allowed and encouraged to develop some independence. I think the fact that a large family precludes it is a feature rather than a bug. But when you keep your only child’s life fairly unprogrammed and unsupervised, it can be a sort of countersignalling, like the multimillionaire who drives an aging station wagon. When you do the same for a large family, everyone knows it’s out of necessity. It’s because you have too many kids to do it “right.”

And then, of course, there’s the mother herself: the more kids you have, the more sick days and appointments you have, the more complicated your household becomes, and the more sensible to have someone at home.7 But that, too, is low status. I don’t want to belabor this point because it sounds whiny, but the fact is that I would be a lot cooler and more impressive to people if I introduced myself at cocktail parties with “I write a popular book review Substack” as opposed to “I’m a housewife.” (I wrote a little here about why housewifery is a satisfying occupation for an intelligent and accomplished woman.) Personally I get kind of a kick out of being counter-cultural so it doesn’t really bother me — and I also spend a lot of time in “seceded” subcultures where I’m not a total weirdo — but it’s certainly a true statement about the world in general, and it plays into people’s choices.

What does it look like on the other side of the unbridgeable epistemic chasm? Being a housewife is low status; what about being married to one? When people find out how many kids you have, are they impressed or horrified? And how do we make “detachment parenting” a high status approach?

John: Being married to a woman who could do all sorts of powerful career stuff but becomes a housewife instead is obviously high status for the man involved. You can tell because: (1) come on it’s obvious, (2) the full-spectrum avalanche of panicky propaganda trying to convince you it isn’t true. So it’s high status, but also transgressive, like being invited to Epstein Island. The more socially acceptable way for a rich man to reap the same status reward is for his wife to do a lot of charitable volunteering, or for her to run a money-losing lifestyle business. Yes, this is perverse. The woman not contributing economically to the partnership becomes acceptable if she also hires a stranger to watch her kids. This is both because housewifery is unacceptably democratic, and because the market is a Lovecraftian monster that desires the financialization of all relationships.

The thing is, all of this matters less and less as “average” men become less important to the economy and society. For example, there was a long time in which sub-Saharan Africa maintained high fertility because having a lot of kids (and a lot of wives) meant that you were a “big man” and who doesn’t want to be a big man?8 But start giving the women cool fake NGO jobs while the men are stuck dirt farming, and suddenly everybody starts having a number of kids that optimizes female intrasexual competition rather than male intraasexual competition. But what’s happened in Africa over the past couple decades is just the first phase of a transformation that’s much further along over here — our education system, HR bureaucracies, and service-oriented economy all favor women on average (plus a handful of male superstars). So there’s only a tiny number of men available that one can be a good housewife for, in all the other cases doing so would be a major loss of social capital. I suspect something like that is the origin of graphs like this.

My interpretation: the negative slope on the left side of the graph represents increasing educational attainment, and greater selection into service professions and corporate environments that favor women’s strengths in consensus-building and conformism. The positive slope on the right side reflects superstar professions (which are male-dominated, probably because men exhibit higher risk-tolerance and larger variance in most traits). In general, the fertility rate is proportional to the ratio of average male to average female achievement, because that ratio is what affects a woman’s willingness to sacrifice her own ambitions and raise some dude’s kids. And we see that that ratio is more favorable to men at the low-end and the high-end of the income scale, and more favorable to women in the middle.

Unfortunately for our birth rate, most people are in the middle. What gives me hope is that that graph also looks like “every class-determined social phenomenon.” Class dynamics are driven by an endless cycle of counter-signaling and counter-counter-signaling. If the lower class likes the color red, then the middle will dislike the color red because they don’t want to be confused with the lower class. But if you’re upper class, liking the color red is a way for you to flaunt the fact that nobody could ever think you were lower class, and also lets you distinguish yourself from the middle class. Real societies have much more complex (and, as Byrne Hobart points out, increasingly illegible) status hierarchies, but you still tend to see this banding pattern which Scott Alexander once memorably compared to a barber’s pole.

So the optimistic case is that this, like heredity of fertility, is another reason that all we have to do is wait and the problem will fix itself. Having 2.1 kids (or 1.6 kids) is a very fuddy-duddy middle-class thing to do these days. All the cool transgressive artists and hyperwealthy Promethean inventors are increasingly discovering that one way to put some distance between themselves and the commoners is to have a zillion kids. Just look at Elon! But inevitably, this trend will slide down the barber’s pole into the fat chunk in the middle of the bell curve that contains most of the population, as people try to imitate their social betters. I’m calling it now — having a ton of kids is on the verge of becoming cool again. (If only the rich weren’t all using surrogates!)

So much for the status explanations, but I find them distressingly bloodless. Analyzing status is like dissecting a joke: even in the best case the patient dies. Chasing after status is the surest way not to achieve it, because the way to get it is to just effortlessly be cool. I think the same is true of trying to replace unhealthy social trends with healthy ones. The real way to pull it off is to just do your thing and to be obviously, effortlessly delighted with your life. Don’t try to “convince” people of anything, just be a shining beacon on a hill, and the world will come chasing after what you have.

And this is the secret wisdom of Carney’s book, and of “detachment parenting” as a whole. The harried, high-intensity parent sends everybody around them a subliminal message of “this is not cool,” and probably harms birth rates on net. The main reason to chill out and have a blast with your kids is that it’s good for you and for them. But another benefit is that being publicly delighted with your belligerent and numerous offspring will make others yearn for your lifestyle. Parenting is often unglamorous, and there’s something as creepy about the Instagram-moms projecting an image of perfection as there is with the travel sports moms engaged in competitive martyrdom. But few things are more awesome than making “thy seed to multiply as the stars of heaven,” and some of us intend to have fun while doing it.

Nothing against the Catholic publishing ghetto! Some of my best friends…

Not that any small child is precisely easy, but some of them will get off the countertop/put down the permanent marker/stop rubbing mud in their hair when you tell them to and some of them will, uh, not.

I hadn’t reread the article since I was in college, but revisiting it now it’s an amazing artifact. “No one is political, no one protests.” Things change!

I suppose one alternative is that the future becomes an ever-shifting adaptive kaleidoscope so that which traits are adaptive is constantly changing, and we never settle down to a new equilibrium. I have a hard time imagining anything happening on the scale of *kids becoming a choice* though, short of the singularity, in which case all bets are off.

It’s trendy in certain parts of the Internet to say that it doesn’t matter how you raise your kids. I’ll admit I played into that a bit in this review, and I stand by everything I said there — babies are not that complicated! But while parenting don’t seem to have a lot of impact on the sorts of things you can measure thirty years later (like income and educational attainment), it still has a tremendous impact on how happy, peaceful, and fulfilling both you and your children find their childhoods to be. Consider Rob Henderson, who seems to be having a very successful adult life in all the ways that show up statistically but had an extremely difficult and unpleasant childhood: that’s bad even if he has a Ph.D. and a book.

In fact, I suspect it’s high status because it’s high effort. In an age of mass affluence, when easy shortcuts are available to everyone, intentionally taking the harder route is a powerful signal of your conscientiousness, industry, low time preference, and dedication to the best possible results. Classy cooking, for example, involves shredding your own cheese and chopping your own garlic; the stuff you can buy at the store already prepped is slightly less delicious but a lot more convenient, and therefore evidence that you don’t care enough about doing it “right” to put in the work. So too with children — except that they are people, and the anxiety and dependence we engender by hovering really does hurt them — and us! Does this make kids like a soufflé? (Actually, stereotypes to the contrary, soufflés are pretty hard to mess up even if someone stomps and yells next to the oven. Ask me how I know!)

Yeah, yeah, it could be the dad, but let’s face it, it’s not.

And the biggest man of them all, of course, is Jacob Zuma.

Okay, I wanted more children and I am now vasectomized and stuck at two. What I noticed is different about "these days" is that the kind of discipline that my wife and I experienced, and that our parents experienced even more, is no longer an option. I was scared of my dad, my wife was scared of her dad. My children are not scared of me. I will never hit them, I will never punish them in ways that could scare or upset them too much. To be clear, it is good in ways not to be feared. My children cuddle up to me, they draw pictures and write "I love you daddy" and give them to me just because they feel like it. I get a lot more warmth and love from my children than my dad did. The problem though is that everything is a negotiation. They get dressed, the older one does her homework etc, but it requires a level of persuasion and nagging that makes handling more than two impractical. What stops me from "detaching" is that we wouldn't get to school on time and homework wouldn't happen and they would get to bed at 11pm.

The widespread availability of cheap plastic toys collides catastrophically with the lower discipline. I let my kids have an hour or two of unstructured play time this morning (it's a holiday here in Canada) and there are sticker pads covering our dining room floor. Part of why I'm always taking them places like Jane is talking about is because they are constantly making messes they don't clean up and if they are somewhere else our house stays clean.

My understanding is that the fall in fertility is almost across the board, even Mormons in Utah are having fewer kids, and I think it's because they are ultimately plugged into the same culture. The Menonites and Haredim are the only people isolated enough to resist the trend.

This website is a nice mixing board for Blue and Red tribe, John and Jane and Trads reading this, how do you manage? Is there a way of having large families without unpleasant (and in Blue tribe circles, basically illegal) discipline?

Excellent summary! I was nodding my head, agreeing with both of you all the way down the scroll bar. Some glosses and flourishes:-

John is not materialist enough, perhaps. Young adults are delaying childbirth. As simple as that. If you start having children at 18 or 20, you can have many more of them than if you start at 32 or 36. It's simple arithmetic and biology. People end up having fewer children than they want, because they start later than they want, or not at all.

This delay does not necessarily depend on the existence of the Pill, nor on procrastination *per se*. Especially if women exercise some agency in selecting mates. It's a consequence of urbanisation and daily lived experience.

In a village, a young woman may have a pool of say a hundred young men from whom to choose. On moving to a city, she sees thousands of men on a daily basis, and is aware of the existence of tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of possibly suitable men, out there somewhere. More choice means more time spent choosing. Humans are weird that way.

Dating apps exacerbate this effect by their mere popularity, leaving aside the misaligned incentives of their makers (to keep people on the apps, not to find them a mate). The apps are an enormous virtual city in which there are suddenly millions of possible choices. That is why they are so awful for everyone (except their owners, bwahahaha jingle jingle).

You both came so close to using the c-word, credentialism, but both shied away at the last possible second. High-investment achievement-oriented parenting makes perfect sense in a credentialist world, which is inherently a zero sum arms race. It's incredibly stressful for the parents and produces damaged kids, but Moloch doesn't care.

(Credentialism explains the U shape of the curve of fertility versus income. I'm sceptical of the scepticism, it's looking like an isolated demand for rigor.)

In a credentialist world the incentives are to delay having children, once again. This explains the shift in marriage from cornerstone to capstone (Delano, 2013): from being an early event in the life of an adult to being the crowning achievement of a successful life.

Homo economicus is not a required assumption for any of this either. People copy what the people around them do.