REVIEW: The Man Who Rode the Thunder, by William H. Rankin

The Man Who Rode the Thunder, William H. Rankin (Prentice-Hall, 1960).

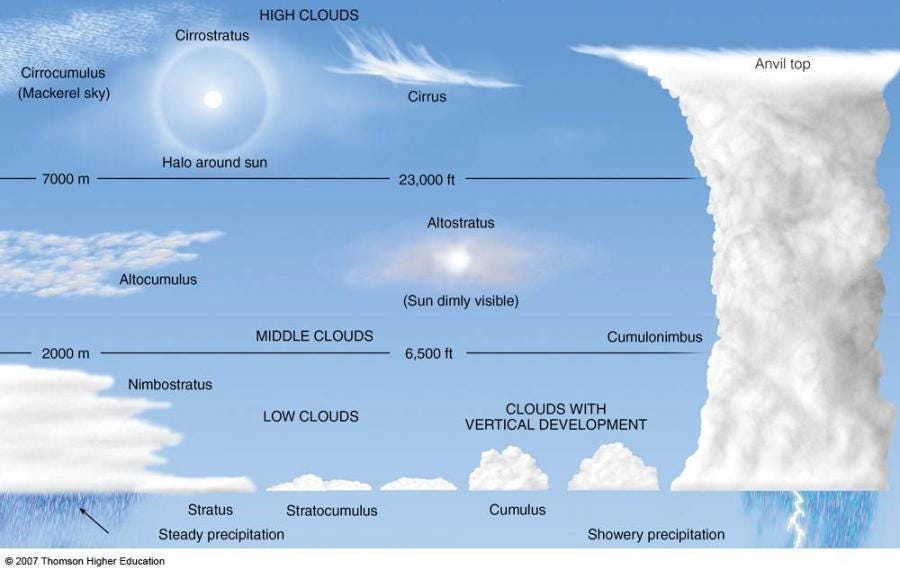

Like many little boys, I loved learning lists of things. One day it was clouds. How could I not love them? The names were fluffy and Latinate, delicate little words like “cumulus” and “cirrus” that sounded like they might float away on a puff of wind. But there was also a structure to the words, intimations and hints of taxonomy. Was the relationship of an altocumulus to an altostratus the same as that of a cirrocumulus to a cirrostratus? I wasn’t sure, but it seemed likely! So here I had not just a heap of words, but something more like a map to making sense of a new part of the world.

So I learned the names of all the clouds, but I quickly got bored of most of them. Only one of them held my attention, but it made up for the rest by becoming an obsession. Yes, it was the mighty cumulonimbus, the towering, violent monster that heralds the approach of a thunderstorm. By then I had already met plenty of them — one of my earliest memories is of huddling with my mother in the room of our house that was farthest from any exterior walls, while lightning struck again and again and again, the echoes of the previous thunderclap still reverberating off the landscape when the next one began. What, I wondered, would it be like to be inside one?

There’s one man who knows. His name is Colonel William H. Rankin, and he fell through a thunderstorm and lived to tell the tale. After his ordeal Rankin published a memoir that was a bestseller in the early ‘60s, but is out of print today. If you click the Amazon link at the top of this page, you will see that secondhand copies of the paperback edition go for about $150. If that’s too steep for you, I’m told that Good Samaritans communists have uploaded high-quality scans of the book to various nefarious and America-hating websites, but this is a patriotic Substack and we would never condone that sort of behavior. Be warned!

I sought out and read Rankin’s memoir for the part where he falls through a cloud, so I was planning on skimming and/or skipping the hundred or so pages where he narrates his life and career up to that point. When I actually cracked open the pdf legally-purchased paperback, though, I found that I couldn’t. Somehow an artifact from an alien world had fallen into my hands. This was a document from a parallel universe with familiar-sounding people and places, but a totally bizarre worldview and culture.

They say you should read books to broaden yourself, to learn about foreign peoples and about cultures not your own. I was unprepared for late 1950s America being as foreign as it turned out to be. There’s a whole genre comprised of parodying the supposed mid-century American combo of sunny faith in scientific progress, squeaky-clean public morality, and blithe indifference to the horrors of industrial warfare. In my own reading and watching, I had only ever encountered the parodies, never the genuine article, until I read this book. Rankin’s memoir exudes gee-whiz enthusiasm from every pore. He is patriotic without a trace of irony, giddy as a schoolboy about advances in jet propulsion, and then uses a totally unchanged tone of giddiness and enthusiasm to describe melting hundreds of Korean peasants with napalm.

Reading this stuff fills me with the same feeling of vertigo that I get reading about Bronze Age Greek warriors — here is a human being just like me, but inhabiting a cultural, spiritual, and memetic universe so different from mine. Are we the same species? If we were to meet each other would we even be able to communicate? Or perhaps every age has had people like him and people like me, and all that’s changed is that the dominant mode of social interaction shifted from favoring one of us to the other. After all, I know people today who are incapable of irony or reflection. For instance, TSA agents. Was 1950s America an entire society of TSA agents? And if so, what am I to make of the fact that in so many ways it seems to have been more functional than America today?

As with any encounter with an alien mind, there are surprising points of connection. For example, consider this description of the intimate coordination required to make close air support effective:

The sine qua non of the art is the speed with which the aviator can work with the forward air controller. In all cases, the forward air controller, who operates with the troops on the ground, is also a Marine aviator. With each other, via radio, we can speak the language of the air or ground. We can think fast and act fast and precisely. Many times in Korea I flew close air support without using a map. I did not need them. Like an infantry officer, I knew the ground action well. I knew every little ridge line, every stream bed, hills, foxholes, frontlines, and could even tell whether an area had been recently raked by artillery fire by noting the condition of the foliage.

This reminds me a lot of my own belief in the importance of a shared language and shared experience between leaders and followers. Only he’s making the additional point that common experience and common assumptions facilitate rapid execution and a tighter OODA loop. This is an insight that the civic religion of 2020s America makes it very difficult to see, implying as it does a concrete way in which certain sorts of diversity make a team weaker. But the core focus on scrappiness, flexibility, and leaders with direct line experience (as opposed to professional managers); all of that would fit right in with today’s Silicon Valley.

My childhood fascination with the cumulonimbus wasn’t just a boy’s fascination with things that are large and loud and dangerous. There were two further facts in my pictorial guide to clouds that I found intriguing. The first was that these brutal behemoths somehow evolved out of the white, fluffy, fair-weather cumulus clouds. The book I had didn’t elaborate on this Jekyll and Hyde transformation, but I was full of questions. Was there a reason that the very least and very most dangerous clouds were linked in this way? How fast did it happen? Were there intermediate stages? What was the point of no return? But beyond all that, what was the secret nature that these two seemingly opposite clouds shared, but that an ordinary stratus rain cloud did not?

The second thing that my book mentioned, but did not explain, is just how unbelievably vast these things are. A normal cloud guide will divide the world into “low-level clouds” (below about 6,000 feet), “medium-level clouds” (about 6,500-20,000 feet), and “high-level clouds” (up to 45,000 feet). Which one is a cumulonimbus? Trick question, it can’t be categorized, because it exists at all of those levels simultaneously. Like a giant whose feet rest on the sea floor and whose head pokes up above the waves.

It took me an embarrassingly long time to discover the answers to these two questions, but to my great satisfaction they turn out to be connected. Cumulus and cumulonimbus do have something in common, which is that they’re both formed through convection (warm air rising).1 I find that the easiest way of understanding this is by taking a monomaniacal focus on energy arithmetic. As you probably know from climbing a mountain, the atmosphere generally gets colder the higher up you go. But we also know from hot air balloons that warmer air wants to rise over cooler (this is just a special case of why things float in any fluid). So the atmosphere in some sense wants to flip itself over. It’s unstable, or meta-stable, like a ball perched at the center of an upside-down bowl — it only takes a tiny nudge in any direction to make it roll away. The amount of energy that would be released if you were to satisfy the atmosphere’s desire to equalize its buoyancy is called the Convective Available Potential Energy, and it can get very large.

Now imagine that we’ve given the atmosphere a nudge. Something has poked a mass of warm air near the earth’s surface and caused it to start rising. Will it rise forever? Generally the answer is no. As the air rises it expands, and that lowers its temperature. It also exchanges heat with the surrounding, colder air. Between these two effects, it eventually equalizes its temperature with the surrounding air and stops rising. But the air is now colder and thinner, so it can’t hold as much water vapor, and some of it condenses into liquid water. The result is a nice, puffy cumulus cloud. The reaction is self-limiting.

What if the same basic mechanism occurred, but the atmosphere got colder faster than the rising mass of air cooled itself? There are actually two ways for this to happen: one is for the atmospheric temperature gradient to be very steep (and the CAPE very high), but it can also happen if the rising mass of air is especially moist. This isn’t intuitively obvious, but water vapor condensing into water actually warms the surrounding air.2 One way to think about it is that the liquid phase is less energetic than the gaseous phase, so that extra energy has to go somewhere, and it becomes heat. But that means a mass of air which is both warm and moist might rise, cool down a little, condense a little, and then the latent heat released by that condensation warms it up a little and causes it to rise a little more… The result is a runaway chain reaction that feeds on itself, like a fire burning out of control.

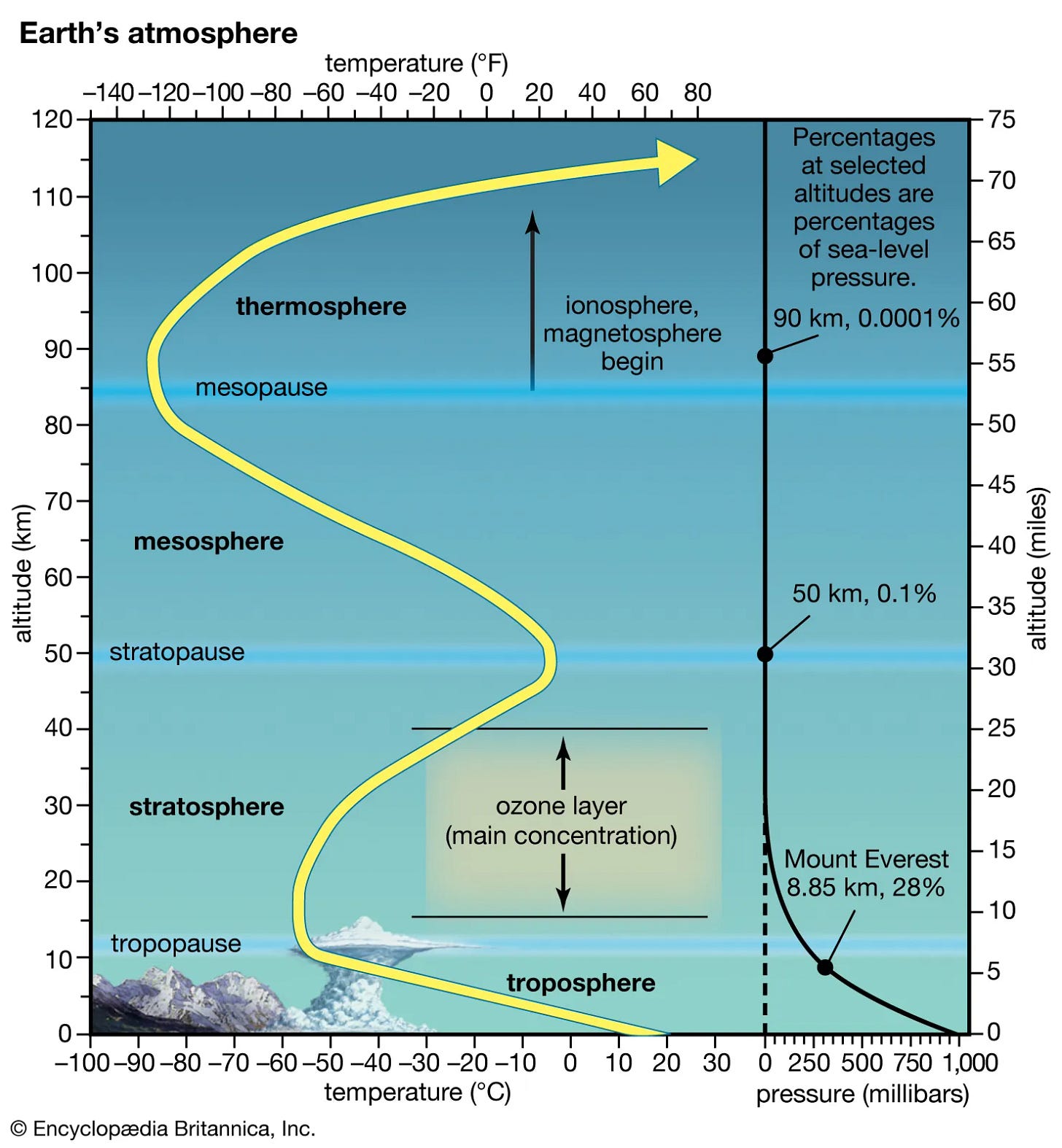

This runaway reaction is called a cumulonimbus cloud, and I think this is a nice intuitive explanation for why they’re so much bigger and scarier than all other clouds. We tend to think of clouds as things, but a cumulonimbus cloud is much closer to a process. It’s a slow-motion explosion, a reaction that is burning up its fuel and converting energy from one form to another. In principle that explosion could just keep getting bigger and bigger, but in practice what happens is the cloud hits the edge of the stratosphere. Something odd happens there — the ambient air temperature starts rising again!

A little bit above the height of Mt. Everest, instead of the air getting colder the higher up you go, it starts getting warmer again. This causes the rising explosion of the cumulonimbus cloud to slam into a wall. The rising air quickly equalizes temperature and pressure with the ambient air, and all it can do is spread out against this invisible thermodynamic forcefield.3 This is what gives thunderclouds their distinctive anvil shape. The magic place where this happens is called the tropopause. It’s the end of the troposphere and the beginning of the stratosphere, it’s about 47,000 feet up when you’re in the middle latitudes, and it’s where Rankin was when his supersonic F-8 Crusader jet had engine trouble and he had to eject directly over a thunderstorm.

On a routine flight down the East Coast of the United States, Rankin encounters an exceptionally violent storm. His plane is rated up to 50,000 feet, well into the stratosphere in temperate regions,4 and so he follows standard procedure and flies up and over the storm which roils against the tropopause like an angry shark pressed up against a pane of aquarium glass. Everything would have been fine but for a freak accident that causes his engine to die. This is worse than it sounds, because the engine of a jet airplane, in addition to providing the thrust that keeps the plane in the air, also serves as a generator powering the plane’s hydraulics, auxiliary systems, and all of the electrical components. So not only is Rankin’s plane about to crash, but he has no radio, no instruments, and no ability to steer.

Fortunately, airplane designers were serious people back then, and had envisioned this contingency, so Rankin’s jet had a little turbine which in emergencies would pop out of the side of the plane to generate electricity and to act as a hydraulic pump, all using the force of the air rushing by. Unfortunately, something else on Rankin’s plane is broken, and the emergency turbine does not pop out as designed. That’s okay, there’s a backup for the backup — a lever on the left side of the cockpit which manually releases the emergency turbine. Rankin pulls it. It doesn’t work. He pulls it harder. The lever snaps out of its housing and comes away in his hand. Now things are bad — his plan had been to glide without power away from the storm and to a much lower altitude, then eject. But without the ability to control the plane, there’s nothing stopping him from going into a tumble or a spin, at which point ejecting means almost certain death. Ejecting at 47,000 feet with nothing but a summer flightsuit on also means almost certain death, but he makes a snap decision and pulls the ejection handles.

Pilots ejecting at much lower altitudes than Rankin are frequently disfigured by frostbite, sometimes losing extremities. The bitter cold of the upper troposphere, and the extreme windchills coming both from the velocity imparted by the plane and from the fall itself, mount a combined attack on any exposed skin. Rankin has ejected right at the tropopause, definitionally one of the coldest places on earth, and on that July morning it’s about -70°, cold enough to trigger frostbite in seconds. Unfortunately Rankin has an even more immediate problem than the cold: “explosive decompression.” At the tropopause, atmospheric pressure is less than a tenth what it is at sea level, and immediately upon leaving the pressurized cockpit of his fighter jet, every air bubble inside his body cavity is trying to rip its way out of him:

I could feel my abdomen distending, stretching, stretching, stretching, until I thought it would burst. My eyes felt as though they were being ripped from their sockets, my head as if it were splitting into several parts, my ears bursting inside… It was nature’s cruelest torture, the screw and rack of space, the body crusher, the body stretcher, each second another turn of the screw, another wrench of the rack, another interminable shot of pain. Once I caught a horrified glimpse of my stomach, swollen as though I were in well advanced pregnancy. I had never known such savage pain. I was convinced I would not survive; no human could.

Despite the pain of freezing and the pain of decompression, Rankin has one thing going for him: he shouldn’t have to endure it for very long. The human body in free-fall will rapidly accelerate to a terminal velocity of over 10,000 feet/minute. Despite having bailed out at an extreme altitude, it should only be a few minutes until he falls into a warmer, denser layer of the atmosphere. This is also why his supplemental oxygen supply is only designed to last for 5 minutes. But the oxygen soon stops and…he’s still falling. In fact, his parachute hasn’t even deployed yet. He feels a flutter of panic: could the parachute’s automatic opener have failed as well? Is he about to slam into the ground at terminal velocity? But no, he can’t have fallen low enough for it to open, because he’s still freezing. But his oxygen has definitely stopped, so it shouldn’t be possible for him to still be in the air. That’s when he glances at his watch and sees that it’s been ten minutes since he ejected from his doomed plane. How can that be possible? He should have fallen through the earth by now! But the reason it’s possible is that he actually hasn’t been falling at all.

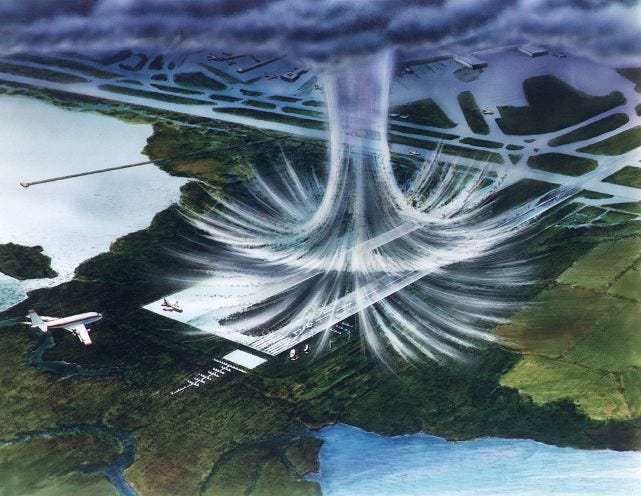

A cumulonimbus cloud is not a thing, it’s a process: an enormous convection cell or heat exchanger between the upper and lower portions of the atmosphere. As it moves, the storms sucks in a river of warm, moist air from the lower atmosphere. This convection current rises to the very top of the storm, cools down, and plummets back to ground level in the form of violent downdrafts. If that sounds a lot like the process leading to the creation of a cumulonimbus cloud, that’s no coincidence at all: the force that births the cloud is also what sustains it. These vertical air movements are what make storms so dangerous for aviation. Glider pilots know well the powerful warm updraft that powers a storm, and call it “cloud suck”, because it can manifest as thermals so strong they seem to pull you into the sky.

More prosaically, this is why storms can seem to “reverse” the direction of the wind just before their arrival. Many an old-timer knows that if you feel a steady afternoon wind that gradually dies and then picks up in the exact opposite direction, it’s time to run for cover. The first wind you felt was the prevailing winds blowing the weather system in your direction, which are then gradually canceled out and overwhelmed by the intake of the storm itself. As the convective current rises in the middle of the storm, air all around the storm rushes in to replace it, causing ground level winds that appear to flow against the oncoming cloud.

In especially large and violent storms, high-altitude shear winds can set this warm air updraft spinning, and the result is a kilometers-wide vortex of rising air called a “mesocyclone.” Storms with an organized mesocyclone that sticks around are called “supercells.” Mesocyclones, despite being giant inverted whirlpools sucking everything into the sky, are generally invisible. But they can also spawn tornadoes, or the lesser known but much more common “anti-tornadoes,” which meteorologists call “downbursts.” Like every good convection cell, a cumulonimbus cloud must have a downdraft as well as an updraft. Downbursts are concentrated blasts of that downdraft — massive gusts coming vertically down out of the cloud and then spreading out upon meeting the ground, leaving a tell-tale radial pattern of destruction.

These powerful updrafts and downdrafts are also the cause of hail. If a large water droplet of the sort that would normally fall as rain gets caught in the updraft, then instead of falling it can get sucked upwards, towards the top of the cloud, where it freezes and falls back down. If conditions are right, this cycle of upward and downward motion can happen multiple times, with the hailstone getting bigger on every cycle. The reason poor Rankin still hasn’t hit the ground is that he’s become a human hailstone, kept aloft in the freezing zone by an updraft or a mesocyclone. If that sounds implausible, we’ve measured upward-directed wind gusts inside thunderstorms that blow at over 110 mph, more than enough to overcome the force of gravity on a human body.

These same upward wind gusts finally fool his pressure-activated parachute into opening, despite the fact that he’s nowhere near the ground. At first this brings relief — he isn’t going to slam into the earth after all. But he soon wishes it hadn’t opened, because the pummeling begins. The human hailstone has met the real hailstones, and they’re all around him, striking from every direction as he tumbles this way and that in the throat of the storm. The relative velocity is immense, the hailstones are large as marbles and hard as rock: they strike him in the face, the belly, the groin, tearing at his flight suit, leaving him with bleeding welts all over his body. He worries that the hailstones are shredding his now-open parachute, which has begun to catch the immense updrafts and downdrafts.

I was pushed up, pushed down, stretched, slammed, and pounded. I was a bag of flesh and bones crashing into a concrete floor, an empty human shell soaring, a lifeless form strangely suspended in air… The rapid changes between positive, negative, and zero g were sickening. I know I vomited time after time... At one point, after I had been literally shot up like a bullet leaving a gun, I found myself looking down into a long, black tunnel, a nightmarish corridor in space.

Soon the rain starts too, so dense he’s afraid he will drown in midair. He laughs at the thought of surviving ejection, frostbite, and explosive decompression, only to be killed by the rain. He imagines being discovered, hanging lifeless by his parachute from a tree, lungs filled with water, and all the government scientists puzzling over how a man could drown in the sky. But even the drowning and the bludgeoning are forgotten when the lightning starts.

The first clap of thunder came as a deafening explosion, followed by a blinding flash of lightning, then a rolling, roaring sound which seemed to vibrate every fibre of my body… Throughout the time I spent in the storm, the booming claps of thunder were not auditory sensations; they were unbearable physical experiences — every bone and muscle responded quiveringly to the crash. I didn’t hear the thunder, I felt it.

…

I used to think of lightning as long, slender, jagged streaks of electricity; but no more. The real thing is different. I saw lightning all around me, over, above, everywhere, and I saw it in every shape imaginable. But when very close it appeared mainly as a huge, bluish sheet, several feet thick, sometimes sticking close to me in pairs, like the blades of a scissor, and I had the distinct feeling that I was being sliced in two.

The lightning has another effect, which is that it lights up his surroundings and enables him to see what no other human being has ever seen — the inside of a storm cloud. It is “nature’s bedlam, an ugly black cage,” with long, dark, narrow tunnels stretching away into the ether. But it’s also a “strange white-domed cathedral,” filled with clouds that boil like “huge vaprous balls.” He has plenty of time to take it in, because he will spend over forty minutes floating in the belly of the storm.

Did Rankin actually see a new kind of lightning, or was it an optical illusion related to being very, very close to an intra-cloud discharge? While doing my own research into this question, I was surprised to discover just how poorly-understood lightning actually is. Some of the mysteries are stuff we’ve all heard of, like ball lightning, which is now fairly well-documented, but largely ignored by scientists because nobody has any idea what it could be.5 But then there’s other, more obscure stuff, for example “superbolts,” lightning strikes over a hundred times stronger than normal. Or positively-charged lightning, which unlike the normal, negatively charged sort, tend to be vastly more powerful, strike farther away, have long-duration continuing currents, and produce vast amounts of low-frequency radio waves.

And then…there’s the really weird stuff.

High in the upper atmosphere, practically in space, there are occasional bright red visual phenomena that look like tentacle monsters and last for a very short time. People had been reporting these for over a century, but it wasn’t until 1989 that somebody finally got a picture of one. Eventually somebody figured out that these things only ever appear over cumulonimbus clouds, at the exact moments of particularly strong “positive” lightning (check out this video for a great demonstration). But nobody knows why, or what the connection is.

The red tentacle monsters are called SPRITES (Stratospheric Perturbations Resulting from Intense Thunderstorm Electrification), and they’re just the beginning. Some decades after the discovery of SPRITES, the space shuttle discovered a different thunderstorm-related phenomenon in the ionosphere. These ones, which look like flattened reddish disks and last only a millisecond, are called ELVES (Emissions of Light and Very low frequency from EMP Sources). Not to be outdone, somebody else added TROLLS (Transient Red Optical Luminous Lineament), followed by GNOMES (not an acronym, sad!).

This is still not an exhaustive list of the weird things that happen in the upper atmosphere over a thunderstorm. Other examples include the more descriptively named “blue jets” and their cousins the “gigantic jets,” which shoot directly out of the tops of clouds. If just in the last few decades we’ve discovered five or six lightning-related phenomena, none of which we really understand, then who’s to say that Rankin didn’t discover another when he accidentally became an amateur scientist and fell through the cloud?

The sad thing about memoirs is there’s no real suspense — you know the guy survived well enough to write it. Not only did Rankin survive, he spent the next few months angrily demanding to be allowed to fly planes again,6 and voluntarily went into a decompression chamber to prove that he was physiologically capable of it. This was the 1950s, and PTSD hadn’t been invented yet. And yet I wondered: how did he feel on warm summer nights, when the air would hang heavy and still, and a distant rumble sounded across the horizon? Fortunately, he tells us that too:

I had been looking forward to a good night’s rest. I was about half asleep in bed when I began to sense a stillness in the air. As I opened my eyes for a glance at the window, a sudden flash of pale light painted my room an eerie blue. In the deep darkness that followed the flash, I knew immediately what to expect — a thunderstorm. …as the intensity of the storm grew, I felt a peculiar compulsion to lie awake, as if to test my nerves against the memory of my ordeal. But instead of fear, I felt a subtle kinship to the storm, almost as if we two had some secret between us that no one else on earth could share.

No fear, no dread. They were men of iron in those days, men made for war. But despite the vast cultural and psychological gulf separating me from this man who lived in my own country a mere sixty years ago, we have this strange point of connection. When a storm rolls in we both lie awake, giddy with anticipation, and happy to be on the ground.

This clears up a terminology question, by the way: meteorologists will refer to thunderstorms as single-cell or multi-cell or a supercell. This is because a thunderstorm is actually a convection cell in the thermodynamic sense!

Water freezing into ice does this too!

Especially powerful and violent cumulonimbus clouds can have what’s known as an “overshooting top” where the momentum of the warm air updraft actually causes the cloud to penetrate into the stratosphere. If you see one of these approaching, it’s time to batten down the hatches.

The height of the tropopause actually varies considerably with latitude — from 30,000 feet in polar regions to a whopping 55,000 feet near the equator. Yes, that means thunderstorms in the tropics are capable of getting much taller than storms in the middle latitudes. Yes, that’s an additional reason that they can get so much more severe in the tropics, even beyond just the generally warmer and wetter conditions.

Ball lightning is not to be confused with St. Elmo’s Fire, another weird lightning-like phenomenon, but one that we understand.

He got his wish to be allowed to fly planes again, so the epilogue of the book is him angrily demanding to be an astronaut.

When German glider pilots, who’d got used to flying ridge lift in the 1920s and 30s, discovered thermals, they got very over excited. Until about 12 of them got sucked up into a huge cunim and all anyone saw of them after that were bits o glider falling out of the clouds. That said, as a glider pilot, you can get very high, very fast, if you’re prepared to give it a go 😂

My Dad was a guy like Rankin, served in some of the same wars as him, and trust me, guys like that were indeed capable of irony and reflection - it just wasn't done in those days to showcase it, especially in a book. Tough survivors were respected in those days, not victims, and, as you pointed out, it is indeed true that men, and women, were tougher back then. Interestingly enough, Rankin lived on until 2009 - I would REALLY liked to hear his opinion on some of the things he saw happen in the US in his lifetime...