REVIEW: Believe, by Ross Douthat

Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, Ross Douthat (Zondervan, 2025).

Imagine a prophet who tells you he has a special understanding of the universe and can predict a far-future eschatological event with certainty. This might be one of the many apocalyptic preachers of a conventionally religious sort, or it could be a different sort of prophecy like the believer in scientific Marxism who has deduced the laws of history, or the charismatic business leader explaining to investors why he will inevitably conquer the world of B2B SaaS.

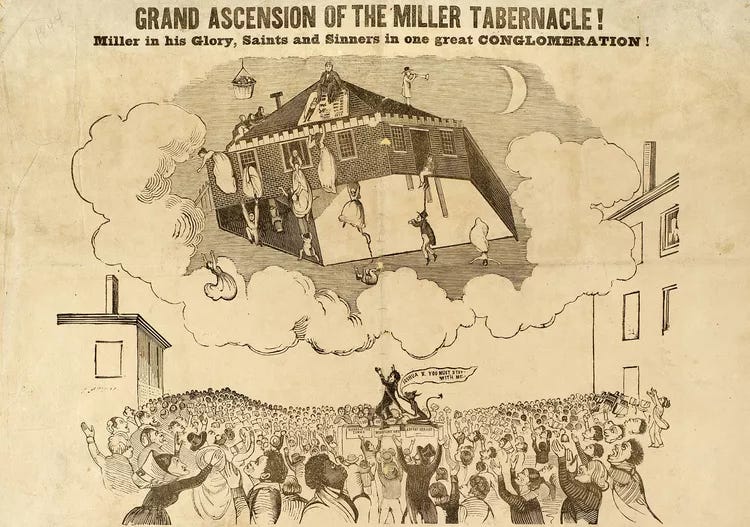

Prophets of whatever sort are often a bit vague about the exact date of the end times (with the exception of the Millerites and Daniel Kokotajlo), but they usually provide a list of more immediate signs and wonders that will herald the ultimate fulfillment of the prophecy. Perhaps they are miraculous events that build up to the final revelation, or they could be the inevitable developmental stages that societies progress through on their way to socialist utopia, or it could be revenue targets for the next few fiscal quarters. When a prophet gets these intermediate predictions right, it’s often good for their credibility. But conversely, how do you feel when a wannabe prophet is wrong again, and again, and again?

I am speaking, of course, of the wrongest and worst prophets who ever lived: the last few centuries of atheists.

People really don’t like it when you point this out, but past generations of atheists made specific and detailed predictions about what would happen as religion loosened its grip on the mind, or what science would reveal about the nature of the universe. Those predictions have been uniformly awful. For example: Enlightenment-era skeptics acknowledged that there were a vast number of purported miracles, apparitions, and self-reported mystical experiences. They conjectured, reasonably enough, that some of the supposed miracles were “pious frauds,” and the rest were delusions brought on by religious superstition. They predicted that as the proportion of religious people waned, both sources of miracles would dry up. Naturally, nothing of the sort has happened (even when normalizing to total population).

Or let’s consider a very different sort of wrong prediction: cosmology. The secularists of ages past just knew that science would soon disprove the Biblical story of creation ex nihilo. They were confident we would discover that the universe was deterministic, eternal, and unchanging. They also expected the number of free parameters in the laws of physics would decline as we got closer to a grand unified theory. Obviously none of this has gone their way. First there was that awful Big Bang theory (invented by a Catholic priest even!) which seems unpleasantly like the kind of thing for which Genesis could be a metaphor (and which was actively opposed by many scientists for this reason). And from there things just got worse — we had quantum mechanics, which Ernst Mach called “darkly metaphysical,”1 and then the triumphant return of teleology, and then a profusion of physical constants that seem both arbitrary and wonderfully fine-tuned for our existence. This is not what David Hume told me would happen.

The fact that the atheists centuries ago were wrong about…approximately everything doesn’t actually have much bearing on whether God exists. Atheism has adapted. Today, instead of telling you that reports of miracles will inevitably decline, they will tell you (with equal confidence) that they will continue at the same rate forever because of…something to do with fMRI machines.2 And the eternal and unchanging universe is back, baby: it’s just the multiverse cosmology of eternal inflation now (which even takes care of the fine-tuning problem).3 There are about as many ways to be an atheist as there are to be religious, so why should we care that one particular set of guys from the 17th through early 20th centuries got repeatedly owned by events?

Ross Douthat cares, because he thinks that much of the intellectual and cultural power of modern secularism comes from a widespread but undeserved sense that the God-deniers have been proven right about stuff. Another way of putting it is that the default position for the intellectually serious has shifted from belief to unbelief. Among the educated class, at least, it used to be only the brave weirdos who were atheists, and now it’s only the brave weirdos who aren’t. Douthat quotes a Tom Stoppard play where a philosopher muses: “It is a tide which has turned only once in human history… there is presumably a calendar date — a moment — when the onus of proof passed from the atheist to the believer, when, quite suddenly, the noes had it.” And Douthat thinks that this shift of the default, this sense that maybe at one point in the past it was reasonable to believe, but that today it is not, is completely 100% made up and unearned, founded on a self-congratulatory retconning of history.

You could summarize the argument as “nothing has actually changed.” Imagine yourself as a stone age wise man or woman, deeply intelligent and deeply convinced that the world is full of gods and spirits. Or imagine yourself as a medieval scholar, investigating the nature of optics, inventing new sorts of algebra, and reading the Bible every night. A committed secularist today can feel some intellectual kinship with the two people I’ve just described, despite the yawning metaphysical gulf. But that kinship comes from a patronizing, yet generous and sincere, sense that “they didn’t know any better back then.” What exactly is it that we know better? What discovery about the universe was made between then and now that makes religion no longer intellectually respectable? We just got done saying that many of the important discoveries actually had the atheists nervously revising their dogmas, rather than the believers.

I have never heard a good answer to this question. It’s true that we know more, and that our knowledge has given us undreamed of power over the world (I am writing this screed from the cabin of an airplane that is transporting me across a continent in safety and relative luxury, with the entire written corpus of humanity at my fingertips). But which of our discoveries have fundamentally changed the character of the universe that we find ourselves in? The most common answers are the Copernican and Darwinian revolutions, which according to the usual story brought us the shocking revelation that mankind’s position in the universe is inconsequential and perhaps even random.

But Douthat argues, and I agree, that this is all quite overblown. It’s undoubtedly true that these discoveries undermined a particular cultural and intellectual synthesis that existed in early modern Europe, but that synthesis was already buckling under political and economic challenges. Did Copernicus really cause the rise of secularism, or were his discoveries seized upon by ambitious princes and revolutionaries who were already chafing at traditional religious authorities? The former story is the one we were all taught in school, but I think there’s more evidence for the latter. For starters, there were plenty of other radical changes in cosmology that the Church happily slurped up, assimilated, and harmonized with its doctrine. For another, the discoveries of Copernicus and Darwin had a much less dramatic impact on Chinese and Indian religious authorities. The myths, rituals, and metaphysics of the East were no more or less compatible with heliocentrism; the discoveries just happened to arrive during a very different political situation.

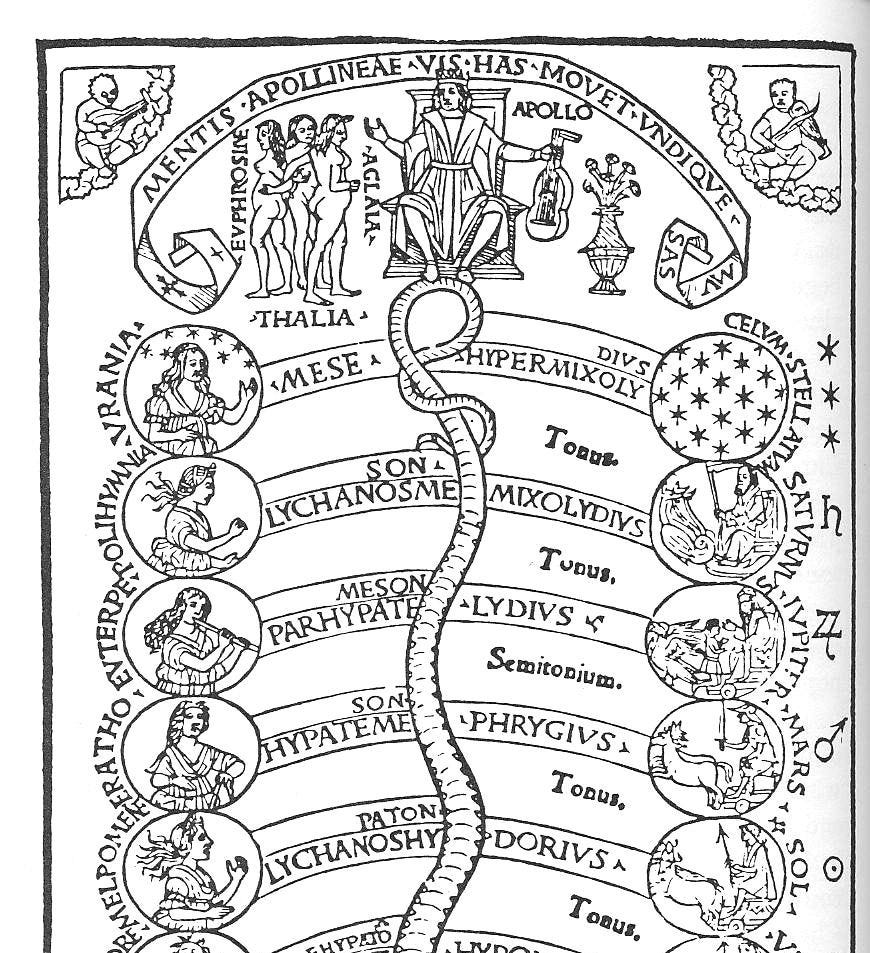

In fact you could even argue, as Douthat does, that these discoveries actually bolstered the specifically Christian picture of the universe, by revealing it to be law-bound at a much deeper level than anybody had ever guessed. We scientists have a curious faith that our questions will have comprehensible answers and that the mysteries of the universe will reveal themselves to our insistent prodding. But there is no a priori reason to assume that this would be so. The extreme version of this argument is Boltzmann brains, but the more moderate version is the countless traditions that have viewed the universe as chaotic or arbitrary (Pope Benedict XVI once got in trouble for pointing out that Islam is one such tradition, and that this could explain why the Muslim world never had a scientific revolution). Far from challenging it, the success of modern science should be viewed as a triumph for the Christian world-picture which holds that the universe was created by a supreme mind, and that we were made in its image to be stewards and custodians of that universe.4

And then there are all the dogs that didn’t bark. Consider, for instance, the Drake equation. Since I was a kid we’ve discovered that those vast spaces revealed by Edwin Hubble are full of more exoplanets than anybody would have guessed, and yet we still haven’t found advanced life. If the atheists like to crow that modern cosmology makes mankind less consequential, doesn’t this discovery make us seem…more consequential? And yet strangely, the world is not full of thinkpieces arguing that Science has now proven that the cosmos is an infinite garden created just for us, so we need to leave our silly nonreligious and materialist superstitions behind.

In fact, once you start looking, there are plenty of other cases where new scientific discoveries could have bolstered the atheistic worldview, but they didn’t.5 The contrarian conclusion is obvious: you live in a conceptual universe that is fundamentally the same as that of the stone age elder or the medieval scribe. It is mysterious, full of wonder, full of order, and gradually revealing itself to us as we increase our power and mastery and knowledge. The world-picture is fundamentally the same, and the claim that it isn’t is self-justifying propaganda in service of an intellectual fad.

Okay, maybe not exactly the same. Our forebears believed that the gods and immaterial spirits played an active role in the world, directly causing miraculous or uncanny events and overturning apparent physical law in a capricious manner. These days, at least among the intellectual and educated classes, we do not believe this. Charles Taylor wrote an extremely long book on this topic, and I touched on some of its implications in my review of a Dostoevsky novel. This is a super significant change, and while it long preceded secularization, I have a hunch that it might have contributed to it far more than the highfalutin’ intellectual stuff we’ve talked about. Anyway, guess what? Douthat thinks you should believe in miracles too!

I really appreciated this part of the book, because I am the sort of deracinated modernist lib Christian who gets slightly embarrassed and defensive whenever the topic of miracles comes up. I’m sitting there at coffee hour after church, and somebody is telling me about how their daughter’s cancer went away after they prayed to St. So-and-So, and I’m smiling and nodding and hoping that it’s true and thinking to myself, “You know, sometimes cancer does just go away,” or, “I wonder how many people there are who prayed and were not healed.” Blame it, if you will, on having read too many Michael Shermer columns at an impressionable age,6 or on being a little too good at seeing through the esoteric writing of that snake Edward Gibbon. I am also acutely aware of arithmetic, and of the fact that with seven billion people in the world, and most of them able to broadcast to an algorithmic feed that amplifies the most interesting and unusual stories, I am invariably going to hear about a lot of events that sounds like they should be so rare as to be impossible.

So this is the book I needed, because Ross Douthat is a very smart man who is also aware of all these facts, and yet he has produced a full-throated and unabashed defense of miracles. He begins by turning my above arguments on their head. Actually, he says, any kind of mystical or supernatural or miraculous event is such a disreputable thing to believe in that (at least if you swim in educated Western circles) you should assume people usually don’t talk about these things when they happen, out of some mixture of fear and embarassment.7 And it isn’t just individuals: the “Official Knowledge” of our society pretty much rules out supernatural occurrences a priori. When it comes to universities, or government agencies, or even the respectable parts of the media, atheistic materialism is somewhere between a powerful intellectual default and an actual institutional requirement. If there were good evidence of miracles happening, probably only crazy people would report on it, and you would either never hear about it or would dismiss it because of the source.

There is a real irony to this state of affairs. The restrictive assumptions of Official Knowledge are more or less directly ported over from the “guild rules” of the scientific establishment, because our system of rule valorizes credentialed experts even when they aren’t literally in charge. And those guild rules of science are the way they are because they’ve been wildly successful for centuries, because the universe really is surprisingly orderly most of the time. And as I said before, much of why science dared to set those rules is itself the outgrowth of a specifically Christian worldview that dominated early modern Europe (this is one of the major subjects of Charles Taylor’s very long book). So in a real sense, it’s the “fault” of Christianity that wondrous and miraculous occurrences are no longer an acceptable topic of conversation in elite circles.8

In the Middle Ages, many miracles had the official sanction of the state, the universities, and all the other epistemic organs of society. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many miracles were recorded. And as I said at the start of this review, secularists like David Hume assumed that as soon as the miraculous lost official sanction and encouragement, the flood of stories would dry up as people stopped claiming or pretending to experience them. But what actually happened was that disenchantment didn’t really happen on the ground. People still report miraculous healings, experiences of contact with a sublime Other, mystical visions, even really crazy stuff like levitation or bilocation. In this respect our society is a bit like a communist one, where the entire ruling class adheres strictly to a certain dogma and everybody else quietly pretends to believe it while actually disbelieving it, because it clashes profoundly with their direct experience of the world. Disenchantment is official but virtual. The official encouragement and recognition of miracles stopped, but the miracles kept pouring in. Douthat discusses many of them, some quite hard to dismiss as an individual’s hallucination or forgery because they were seen by many witnesses, others reported by committed materialists who recount them the way a religious believer might shamefully discuss almost losing their faith. Or as Chesterton once put it:

The believers in miracles accept them (rightly or wrongly) because they have evidence for them. The disbelievers in miracles deny them (rightly or wrongly) because they have a doctrine against them… it is you rationalists who refuse actual evidence being constrained to do so by your creed.

But isn’t the very torrent of miracles itself a problem for believers? After all, one of the most noteworthy things about wondrous or uncanny or miraculous events is that they seem to happen worldwide, to people of every imaginable creed or culture, at roughly the same rate. Shouldn’t this count as evidence against most religions, which claim that their own doctrine is true and all others are false?9 Curiously enough, no. If you actually go and look at how even the most jealous and narrowminded faiths in history interpreted the miracles reported by heathens, you find that basically none of them deny their reality. Frequently they will interpret the miracles bestowed upon followers of rival religions as acts of diabolical rather than divine power, but only very rarely do you see them claiming that they are fake. Chesterton again:

No religion that thinks itself true bothers about the miracles of another religion. It denies the doctrines of the religion; it denies its morals; but it never thinks it worth while to deny its signs and wonders.

Nevertheless I, like Douthat, do actually think that one religion is more true than all the others. And here we see one more example of how the predictions of past generations of atheists have failed to come true. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, European academia was dominated by people applying the techniques of source criticism to Christian religious texts — especially to the four canonical gospels. These writers brought great verve to their task, challenging the traditional attribution of authorship of much of the New Testament and digging up all sorts of apocryphal writings that had been excluded from the scriptures for supposedly political reasons. At the height of this movement, it was common knowledge among “educated” people that the Gospels had been written hundreds of years after the events they described, that most of the early Patristic and Christian Neoplatonist writings were medieval forgeries falsely attributed to ancient authors, and that the “historical Jesus” was a political freedom fighter who never claimed to be the Messiah — or possibly who never existed. It seemed like the foundations of the Christian religion had been demolished, or at the very least unsettled, and everybody expected that this trend would continue.

Instead, it turned out that most of the revisionist scholarship was completely fake.10 I’m a little frustrated that this story isn’t better known, because it ought to be one of the biggest scandals in the history of academia — bigger in my view than the slow-motion replication crisis that’s currently hitting social science and medical research. As I mentioned in my review of The Cruise of the Nona, academics tend to get unusually excited and sloppy when they think they’re “overturning” received wisdom, and this vastly increases their error rate. It’s true of revisionist attempts to overturn traditional archaeology (which are now being totally disproven by population genetics), and it was true of 19th century Biblical criticism too. These writers were so delighted with themselves for freeing mankind from superstition, so giddy at their own edginess, that they made inexcusable factual mistakes and logical leaps. Their scholarship was basically one big circular argument, where starting from secular assumptions they argued their way via epicycles to a secular conclusion.11 But many of the specific, concrete historical claims that made the whole edifice hang together have lately turned out to be totally false. Surprisingly, the unearned triumphalism of the 19th century writers still pervades academia because, well….we all know the answer, and it really isn’t very surprising, is it?

All of this sound and fury and debate over who wrote the story has a way of distracting us from the story itself, and I’d like to end this review by encouraging you to read it even if you don’t believe it. The narrative of the Gospel has been the single biggest influence on the millennia-old civilization that you (probably) are a child of. But it isn’t just the story of that civilization, because it’s also somehow had an electrifying effect on just about every other culture that’s ever come into contact with it. Forget all your beliefs or disbeliefs or presuppositions, doesn’t that sound interesting? Isn’t that the sort of thing that an educated person in the year 2025 should have direct experience with?

So pick a Gospel, any Gospel (yes, they have some important disagreements on the details,12 but the overall story is the same), and try just reading it through from start to finish. Maybe next week would be an auspicious time. And as you read, try to forget all the associations you have with Christianity, positive or negative, and read the words. If you want, you can imagine yourself in the cultural frame of the first people to encounter the story, and who were much more shocked by it than you will be. But even you, who have spent your whole life subtly marinating in the moral and cultural world that this story built, will be a little bit shocked if you read the words. Because just taken at face value, it’s a really weird story.

It begins, like countless Indo-European myths, with the miraculous birth of a great hero, and a succession of dangers that befall him in childhood. This is classic perennialist stuff, maybe the biggest cliché ever, repeated in myths and legends all over the world. Maybe that should bother Christians, because it means our story is one myth among many others. Or maybe it shouldn’t, because if our story is true, then it is in a sense the story, and we should expect to find echoes of it in all times and places, like refractions in a funhouse mirror. The one thing that’s already strange about this story, though, is how insistent it is on its own specific historicity. All the other myths and legends of demigods and heroes tend to begin with something like: “long ago when the earth was young,” or “once in a strange and faraway land.” But this one has dates, and at the time it was written those dates were recent! It cites names of witnesses, and mentions specific people and places. That doesn’t make it true, of course, maybe they all made it up in a conspiracy of lies, but it does make it different from most legends of a great hero sent by the gods.

Anyway, the hero is born, survives his childhood trials, is officially recognized and charged with a mission by the gods, and then begins roaming the countryside: recruiting a fellowship, righting wrongs, and lifting up the sorrowful. Once again, we’re solidly in monomyth territory, this is the plot of like every adventure story ever. But wait a minute…look more closely and the details are all subtly wrong. Like, the “meeting the mentor” stage of the hero’s journey isn’t supposed to have the mentor immediately proclaiming the young hero as Lord. And then there’s the wandering part — most of it just seems to involve upsetting or confusing people. Zero monsters are slain. Zero Roman legionnaires are ambushed or waylaid by this supposed revolutionary folk hero. His only really heroic acts are miracles of healing, but whoever heard of a legend of a Great Physician? And the people who get the healings tend to be ones who, in the view of this society, don’t deserve it — heretics, prostitutes, lepers, the possessed — all of them “unclean.” Some of the healings even deliberately violate the law. Is he the first ever anarchist, come to overthrow not only the Roman occupation but also the rules of the Jewish religion? Is he a prophet of just using common sense and being nice to each other?

No. At other times He makes the law more restrictive, sometimes to an almost unbelievable degree. There were already rules against adultery, but this new hero, or prophet, or whatever He is demands perfection. “But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart. If your right eye causes you to stumble, gouge it out and throw it away.” (Matthew 5:28-29). I’m sorry what? Just who does this guy think He is? And yet His morality gets even weirder than that. Many of the worlds religions, philosophers, and sages have roughly converged upon a recognizable set of ethical principles for being a just and righteous man. You know what it doesn’t include? “…do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well… love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” (Matthew 5: 39-44). This is an impossible standard and seemingly insane advice. In most places, following it is the equivalent of slow suicide.

His morality contradicts every normal human intuition about fairness, but He seems oddly unconcerned about fairness. Often, as He wanders the countryside healing and upsetting people, He explains His view of the world in simple stories. The stories are about everyday things familiar to the agrarian population of first century Palestine, sheep and vineyards and olive trees and rapacious officials, stuff like that. But think a little too hard about any of these stories, and they make no conventional sense at all. “You know how sometimes you have a hundred sheep?” I imagine everybody nodding along at this point. “Well, if one of your sheep went missing, wouldn’t you ignore the other ninety nine, and spend all of your time looking for the lost one?” Yeah, totally… hey, wait a minute! No, I would not do that. That is not what any sensible shepherd would ever do! Ninety nine is a bigger number than one! But He’s already moved on: “So you know how when you have a group of vineyard workers who work all day, and another group who only show up at the last minute, and then you pay both groups the exact same amount, and…” NO! I do not know that, because that does not make any economic sense at all, ARGH. But He has no time for your arithmetic born of scarcity, because He lives amidst infinity, and keeps telling you, maddeningly, that you do too, and that by giving yourself away you’ll have more left than you started with.

The weird story has a weird ending. He makes a grand triumphal entrance into the capital city, in accordance with a bunch of famous ancient prophecies. But again, if you look closely all the details are subtly wrong. Rather than ride in on a majestic war-horse the way a great hero should, He instead rides on a donkey. And where’s His sword? It’s simultaneously like a royal procession and a parody of a royal procession, on different levels. Rather than say anything that would make Him popular with either the mob or the authorities, His preaching turns bleak and apocalyptic. He prophecies the destruction of the city. The man is clearly skilled with words and has picked up quite a following. Wasn’t He supposed to deliver the people from their oppression? He could whip up a riot and try to take over the city if He wanted to, but instead He castigates the religious leaders. But weirdly He seems most angry about the things that everybody knows just have to be that way, like selling sacrificial animals at the Temple. The performance leaves even His supporters confused and upset. One of them tips off the authorities, and He is stealthily arrested, tortured, and then publicly executed.

There are people who will tell you that Jesus did not rise from the dead, but that He was a great moral teacher with a lot of good advice. But if He didn’t rise from the dead, then wasn’t it actually the worst advice ever? The example Jesus provides is an example of how to get killed: first you make people jealous, then you make them mad, then you confuse and demoralize your followers, then you refuse to speak in your own defense. If the real story ended with the Crucifixion, then surely it’s a story about what not to do. The lesson we would draw from it would be, “Don’t imitate Jesus, imitate the worldliness and adaptability of the Jewish elders, imitate the power and cruelty of Rome.”

The whole question then, the one on which our interpretation of this very strange story ought to hang, is what really happened on the third day after the execution. The story’s version is that He came back to life and spent weeks walking around and talking to people before vanishing again. Though here again, the story is weird. The Gospels all note that many of the people Jesus knew best didn’t recognize Him at first. That detail raises all kinds of doubts and troubling questions, and seems like a very odd thing to include in the story if you were just faking it. But the story is what it is, and dozens of the people that supposedly encountered the risen Jesus would later go through agonizing tortures and cruel deaths because of their unwillingness to say that they had made it up. Even if you don’t believe in the Resurrection, it sure seems like something quite unusual must have happened there.

What that something was, I leave up to you. Neither Douthat nor I is here demanding you convert. But if you do read the story yourself, and if — like many before you — you find that you can’t quite shake it out of your mind, then my advice is to keep asking questions. For the master of the vineyard promises the same reward both to those who have labored from the first hour and to those who arrive at the eleventh hour.

Yes, there are strictly deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics. The obvious one is de Broglie–Bohm theory, but if you squint, Many Worlds is deterministic too (you have to imagine that the Born probabilities are just a measure on the total number of universes). And yet… I don’t think any of this would have made quantum mechanics seem less “darkly metaphysical” to a nice 19th century positivist.

I sometimes feel that I make fun of the field of evolutionary psychology a bit too often, since it has made some real contributions to our understanding of the world. But man… they make it hard not to sometimes. The arguments for why mystical experiences or near-death experiences would provide an advantage in either individual or group selection are particularly egregious just-so stories (in the latter case, you are multiplying whatever subtle fertility effect you’re imagining by the vanishingly small proportion of people who have near-death experiences and then come back from them). If I were an atheist, I would just say that they’re spandrels of our cognitive architecture and leave it at that.

Speaking of the multiverse, Scott Alexander recently injected Tegmark’s mathematical universe hypothesis into the discourse. I’m an old fan of Tegmark’s, and I like Scott’s blog, but I found the discussion around this to be atypically low-quality. I will confine myself to a few remarks:

(A) The MUH in its weak form does not address the question of why there is something rather than nothing, and in it’s strong form it literally is God. Like, you’ve just invented deism.

(B) Scott waves his hands and says “in order for the set of all mathematical objects to be well-defined, we need a prior that favors simpler ones.” This is a very confused statement, or at best an incomplete one. I assume that what he’s referring to here is Section 7 of Tegmark’s paper where he proposes an alternative possibility that only computable mathematical structures exist. But there are two big problems with this: first, it’s completely unmotivated. The attraction of the MUH is in its sheer, unbridled, over-the-top ontological exuberance. Its answer to “why do these things exist” is “everything exists.” To then say that only computable structures exist (and why computable? Are we running on a computer somewhere?) moves us back into question-begging territory. But the bigger problem is that it doesn’t actually address the problem of comprehensibility at all. Within the set of all universes with computable descriptions, the subset with comprehensible time-evolution is still infinitesimal. I’m sure you can come up with ever more strained weightings of the various possible universes, but again doing this vastly increases the number of bits needed to describe the multiverse as a whole, greatly reducing the attractiveness of the theory. You move from a principled sort of modal realism to a very ad-hoc convenience sample of worlds.

(C) Those interested in the problem of comprehensibility should read the other Tegmark paper. We really do live in a world that is mysteriously easy to understand.

One possibility that James Chastek hipped me to is that there is “nothing at the bottom.” Beyond quarks we will find sub-quarks, and beyond those the sub-sub-quarks, and so on forever, all of them organized and rule-bound by ever more beautiful sorts of mathematical structure, spreading like the petals of a flower. A beatific vision worthy of eternal contemplation, already placed here. For us.

Douthat spends considerable time on the science, or lack thereof, concerning the material origins of consciousness. In the 18th and 19th centuries people were pretty confident that we would just figure this out, but now it seems so much thornier and less in reach that people call it “the hard problem.”

Speaking of America’s most famous skeptic, Douthat begins his chapter on miracles with an anecdote about Shermer that is too wild and too unexpected for me to do it justice with a summary here. Read the book!

I suspect Douthat is right about this. Out of curiosity, I once surveyed a few of my most straight-laced and secular acquaintances by getting about one and a half beers into them and then asking questions like: “has anything really inexplicable or miraculous ever happened to you?” I heard some insane stories.

Yes, I also acknowledge that Christianity is in tension with itself, insofar as it both claims that the world is law-bound and allows for wild irruptions of divine power that overturn the laws of nature. The best thing I’ve read on this topic is the second of Sergius Bulgakov’s essays in this book.

A related claim, which I see a lot, is that the very multiplicity of religions should count as evidence against all of them. Richard Dawkins and Stephen Roberts both love the line that goes something like: “all of us are atheists about 99% of all gods that people believe in, we just disbelieve in one additional one.” (This line, like pretty much everything else in Reddit atheism, was originally stolen from David Hume.) It’s also very silly. There’s actually a remarkable convergence in the core metaphysical claims made by the Western monotheisms, Buddhism, Daoism, and Hinduism (this sometimes gets called “classical theism”). Is it really so hard to imagine that one of them gets the nature of reality basically right, and the others are distorted or incomplete versions of the truth?

If you’re interested in this, I recommend Benedict XVI’s books on the Gospels, or N.T. Wright’s The New Testament in its World as good lay-friendly entry points. Both are great in themselves, but the bibliographies are a true goldmine.

I originally made a QAnon joke here, but decided most people wouldn’t get it.

[19th century Biblical scholar voice]: “They disagree on the details because none of them were there, and they’re all pastiches of these three other documents, one of which is called ‘Q’, and so first they cut and pasted something from the Pseudoapokalyptikon of Nicodemus, and then there was a transcription error in the Great Blender Disaster of 176 A.D., but it can’t have happened before Josephus wrote his Annals, so…”

Or, alternatively, eyewitnesses to an event often remember it in different ways. Especially when they’re writing it down years later.

You commit a rhetorical sleight of hand here, where you bring up the Copernican and Darwinian revolutions, formulate an argument to dismiss the Copernican revolution, and then proceed as though by doing so you've repudiated both. In fact, I'd argue that Darwin is - both in popular understanding, and in historical fact - the greater pivot point here, not Copernicus. The Earth going around the sun is less a blow to Biblical narrative than the evolution of man from ape.

To be clear I don't think you're being glib. I suspect you were just trying to avoid miring your argument in some long and thorny weeds. I'm sure you've thought long and hard about Darwin, as you strike me as the kind of person who thinks long and hard about these kinds of things. But I'd be far more interested in hearing your thoughts on Darwin than on Copernicus, so I was disappointed by the elusion.

As for miracles... An atheist might say that human psychology is the constant baseline here, not the existence of miracles. People have a natural tendency to believe things that aren't true.

While your pen remains as sharp as ever, I find the arguments here lacking their usual point.

First: are you and Douthat really suggesting Genesis holds up better than Enlightenment cosmology? You allow Genesis to be metaphorical while mocking atheists for failing to anticipate 21st-century physics. But by any standard, the Bible’s cosmology isn’t accurate—and letting scripture be “basically right” while demanding literal foresight from secular thinkers is a stacked deck. If anything, the most accurate religious cosmology is probably the Old Norse, they got the beginning AND the end, for what is Ragnarok but the heat death of the universe, or a Big Crunch if the energy density is sufficient? I joke, but you see my point here.

Second: from a previous piece—you’ve still misunderstood the teleology of Lagrangian mechanics. The endpoints or boundary conditions are imposed by the problem. The teleology is formal, not metaphysical, and vanishes in a differential formulation, just like in local and global formulations of Maxwell’s equations. It’s not evidence of purpose—it’s just math.

Third: your claim that miracle frequency has stayed constant (even normalized!) is unsupported and likely wrong. Reports of miracles clearly track cultural trends—dropping during Enlightenment cessationism, rising with Pentecostalism, declining as the Vatican tightens standards for healing miracles at Lourdes. That’s exactly what you’d expect if they’re socially constructed, not supernaturally driven.

And even if I granted the whole structure—fine-tuning, miracles, moral profundity—none of it uniquely confirms Christianity. One could just as easily use this framework to rationalize Islam, or Hinduism, or Atenism. You and Douthat address this a bit in the article, but not enough. If everything vaguely theistic counts as “confirmed,” then nothing in particular is. And what’s faith anyway, if it’s just empiricism after all?