REVIEW: Cræft, by Alexander Langlands

Cræft: An Inquiry Into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts, Alexander Langlands (W. W. Norton & Company, 2017).

One great thing about writing a Substack about the books you like is that now everyone knows what kind of books you like, which means they can recommend more. This is one of those: I had been rhapsodizing about the BBC historical farm series in both my reviews of Ruth Goodman’s books, so someone told me one of the other presenters also had a book. I read it. I loved it! And then I didn’t review it, because while I am perpetually fascinated with the material culture of the past I couldn’t really think of anything interesting to say beyond, “Hey guys, who wants to hear about hedges?” (I would never do such a thing.)

Of course this isn’t just a book about hedging, that would be silly. There’s also haymaking, shepherding, walling, beekeeping, weaving, tanning, basketry, thatching, plowing, and the making of everything from ponds to quicklime, because Alex Langlands is obsessed with preserving (and if necessary recovering) the skills of the rural past. He wants you to understand what’s been lost to industrialization, and how our contact area with the world has shrunk, and why doing things with your body is part of being human, and…oh wait I’m sorry I nodded off, because I’ve written this all like twelve times already.

So why am I telling you about a book on how to do things by hand that you can do far more quickly and efficiently with a machine?

Well.

Langlands frames his book around the concept of cræft, which (as you can probably guess from that æsc) is the Old English origin of our modern “craft.” The ancestral word is richer and more complicated than the modern one, though, pointing to far more than handmade tchotchkes and beer with too much hops. The Dictionary of Old English explains:

“Skill” may be the single most useful translation for cræft, but the senses of the word reach out to “strength,” “resources,” “virtue,” and other meanings in such a way that it is often not possible to assign an occurrence to one sense in [modern English] without arbitrariness and loss of semantic richness.

Like the modern “craft,” it does convey a sense of ability, especially when it comes to one’s livelihood: the students in Ælfric’s Colloquy use cræft as well as weorc when discussing what they do all day. But it can also mean might or power: when the Old English Orosius tells us that the strength of the Medes failed them in battle, for example, it’s Meða cræft that gefeoll,1 and when Judah Maccabee’s foes join the fray, they begin to fight mid cræfte. Of course, there are semantic connections among these varied meanings: the ideas of physical strength and physical skill blend into one another at the edges, and a word for a thing you’re good at doing with your hands can also be used for a thing you’re good at doing with your mind. (After all, we still refer to writing as a “craft.”) And ideally you’re fairly talented at whatever set of things provide your livelihood! So we can say that Old English cræft broadly means something like “a person’s ability to bring his will to bear on the world, and his skill in doing so.”

There’s one more meaning, though, and it appears more or less exclusively in the writings of Alfred the Great: cræft as spiritual or mental excellence.2 Anglo-Saxon scholars had mostly used cræft as a way of rendering Latin ars, but when King Alfred translated Boethius into Old English he used cræft for Latin virtus, virtue as in moral excellence.3 A contemporary reader might be tempted to see this as merely an extension of the “mental skill” sense of the word (a virtuous person is one who is good at being good), but that would be misleading; the general meaning of cræft leaves the word freighted with powerful and inescapably physical implications. (Remember, too, that before the Reformation the Christian image of spiritual excellence universally emphasized asceticism, which necessarily involves the body a great deal.) Cræft as virtue is not an internal moral condition, it’s an internal activity, a kind of doing or making of the soul.

Or, as Langlands glosses his title, cræft is “a hand-eye-head-heart-body coordination that furnishes us with a meaningful understanding of the materiality of our world.”

Langlands is now a professor of archaeology at Swansea University, but he got his professional start as a circuit digger, the kind of “hired trowel” real estate developers pay to quickly catalog all the ancient remains they’re about to turn into the foundation of a new Tesco. It was not a fulfilling job — “crude and expedient” is the line he uses for his commercial excavations — and he was beginning to grow disillusioned with archaeology as a field. So naturally he did what any sensible person would do if he didn’t like his job: he applied to be on a TV show. This was in 2003, and BBC Two was advertising for people to spend a year in 1620, living on and running a historical farm using reconstructed period techniques and equipment. Langlands got the gig (along with Ruth Goodman and another archaeologist whose book I haven’t read), and had a wild year in the Stuart era and then a few more in the Victorian and Edwardian periods.

The shift from examining the archaeological record to experiencing how it was made was an eye-opener, and the success of that first program took him by surprise: “I’d often wondered to myself who on earth would want to watch a bunch of cranky, oddball re-enactors and archaeologists bimbling around in costume, pretending to be in the past,” he writes. “But I didn’t care too much because I was spending nearly every single hour of every day immersed in historical farming. I was tending, ploughing, scything, chopping, sweeping, hedging, sowing, walling, slicing, chiselling, digging, sharpening, thatching, shoveling; the list was almost endless.” And the longer he spent doing all these things (he was on three more shows), the more he realized that the skills, and the knowledge they required, were slipping away.

True cræft, in Langlands’s version, is a combination of know-how and make-do. It’s when you live on the Outer Hebrides and don’t have any trees, so you use whatever driftwood washes up as the ridgebeam for your roof. No timber for the rafters? No problem — a sufficiently strong rope, drawn tightly enough over the ridgeline and secured on both sides, makes something like a giant net on which you can lay your thatch. The straw left in the fields after harvest will do nicely for making both rope and thatch, but if (say) it’s the early twentieth century and you’ve abandoned cereal crops because cheap North American grain knocked the bottom out of the market, then you can make rope from heather and thatch with bunches of bracken. (On the Danish coast, they use seaweed.)

Or it’s when you’re an early Anglo-Saxon who wants to boil some water. A few generations ago, some Romano-Briton on the same spot would simply have bought a beautifully thrown pot from any one of a dozen proto-industrial centers across the Empire, but these days that production has slowed or stopped and the trade networks that would’ve brought them to you are kaput anyway. All you’ve got is some lousy local clay, too weathered to be easily worked. You don’t even have the fuel to fire it hot. So you add organic tempers like grass or chaff (or even dung) to make the clay more plastic, you shape it by hand without a wheel, and when you fire your pot the chaff burns away and leaves tiny voids in the ceramic. Your pot is soft, it’s brittle, it’s kind of lumpy, and fifteen hundred years from now Bryan Ward-Perkins is going to point to it as evidence that civilization collapsed when Rome fell — but it’s still a pot, and it still holds water. You’ve made ingenious use of the world around you to solve your problem. You are, in a word, cræfty.

So when Langlands says cræft, he means the way people behave under conditions of scarcity and resource constraint. And when you’re in that kind of situation, of course you have to be intimately familiar with all your materials — you have to squeeze every last drop of performance out of them! And while Langlands is interested in preindustrial techniques, this isn’t just a matter for drystone wallers and skep-making beekeepers; you can also be cræfty with machines or computers. Cræft is the Havana mechanics who keep 1950s cars running on an income of $40/month, or the engineers who fit all the computer code for the Apollo Guidance Computer into 80 kilobytes. It’s the defining feature of the Real Programmer who “tuck[ed] a pattern matching program into a few hundred bytes of unused memory in a Voyager spacecraft that searched for, located, and photographed a new moon of Jupiter.” We rightly admire these cræfty solutions for their elegance and their makers’ skills, but aside from a few weird hobbyists we don’t imitate them. You don’t spend days hauling rocks and building a wall to keep your sheep in when you have wire fencing. You don’t learn the skies so you can time your haymaking for clement weather when you can just wrap your machine-mown grass in plastic and make silage instead. And you don’t work in unreal mode when you have 64-bit processor. Technological advances have freed up our time precisely because they’ve freed us from the need for clever, thoughtful, material-aware solutions to our problems. No one is cræfty in the midst of abundance, because they don’t have to be.

Your reaction to that last paragraph reveals where you fall in the Wizard/Prophet divide: are you pumping your fist for humanity, or are you a little sad that a kind of mastery has been lost? Is our ability to simply throw more resources at the problem and go on with our day a blessed liberation from the bonds of brute necessity, or is it a tragic separation of our thinking, making, doing selves from our world? Are our practical limitations something to be defeated or innovated around, or are they something to embrace because they are, in some sense, good for us?

Langlands is, unsurprisingly, well over on the Prophet side. He warns that “while some machines are clever, the net result of our using them is that we become lazy, stupid, desensitized, and disengaged” — it’s not that a thing made by hand is better as an object than its mass-produced counterpart (although in some cases it is, and a stone wall does last longer than a wire fence), it’s that the making changes the maker. And while he likes to warn that climate change or Peak Oil or the fragility of international supply chains make our uncræftiness a serious survival risk (think of those poor imported-pot-dependent Britons when Rome withdrew!), that’s not really the point. Even if our technological society never falters — even if we soar to greater and greater heights of prosperity and can afford to automate and mechanize more and more of our interface with the world — Langlands argues that would just mean more missing out.

Which brings me back to AI.

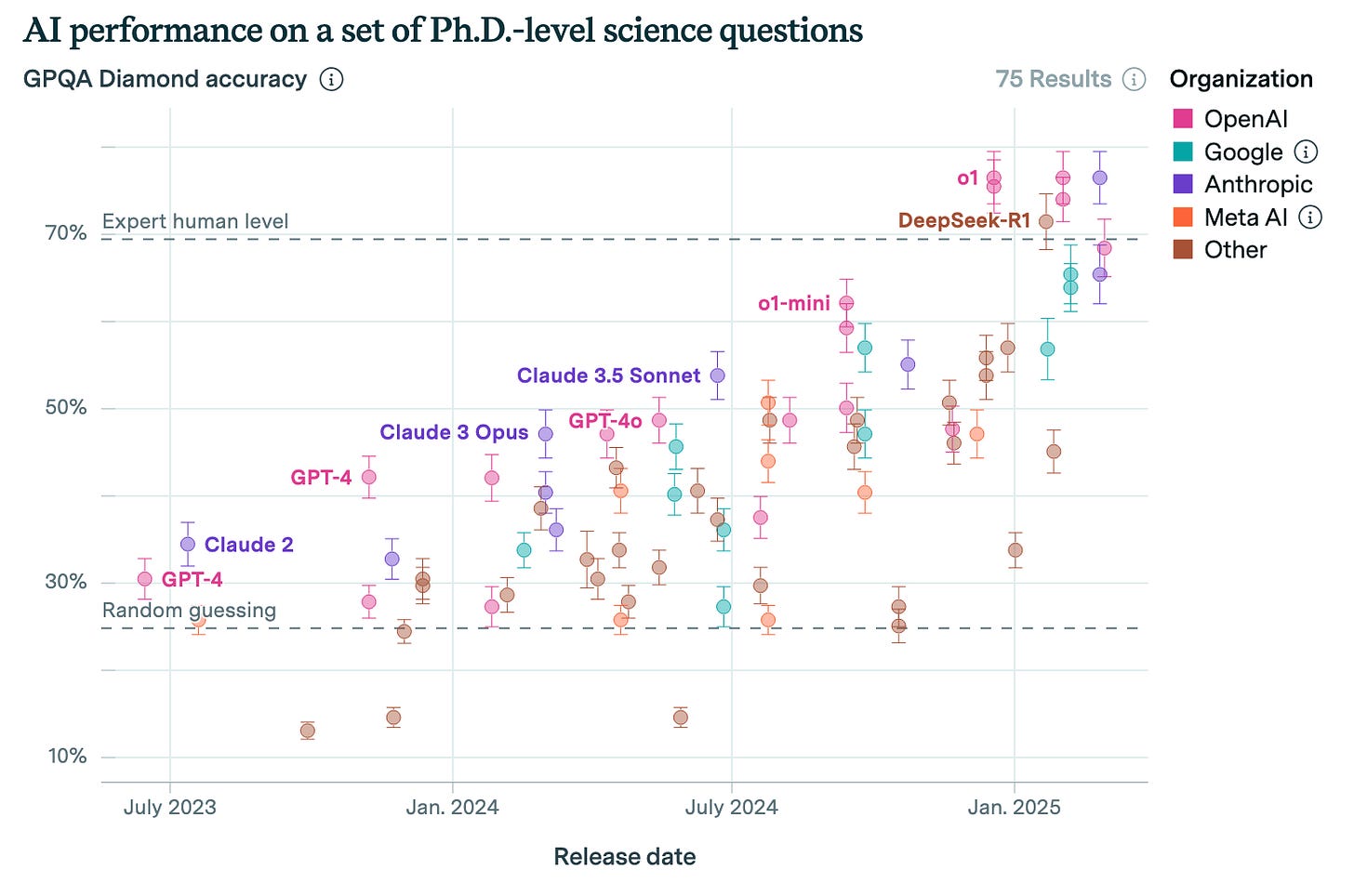

It’s always a little dangerous to write about any rapidly-developing technology, because chances are pretty good that whatever you say will be incredibly and obviously dated within a few months. But I’m going to plant my flag anyway, because even if nothing else changes — even if there’s no meaningful advancement in LLM performance beyond the state-of-the-art right now, in March 2025 — the potential disruption is already so enormous that you can think of it as a kind of Industrial Revolution for text.

Just like in the first one, we’ve figured out how to use machines to do a broad swathe of things people used to do, swapping energy and capital in for human labor. And just like in the first one, the output isn’t necessarily better (in fact, it’s often worse), but it’s so much cheaper in terms of human time and thought and effort that the quality almost doesn’t matter. Sometimes that’s wonderful: if you desperately need to put a roof for your barn right this moment, it’s a blessing to be able to slap on some corrugated tin instead of going to the effort of thatching. When you have to write your seventeenth letter to the insurance company explaining that no, they really ought to be covering this, it’s a relief to hand the composition off to Claude instead. But do that too much and you forget how to do it yourself — or more plausibly, you never learn.

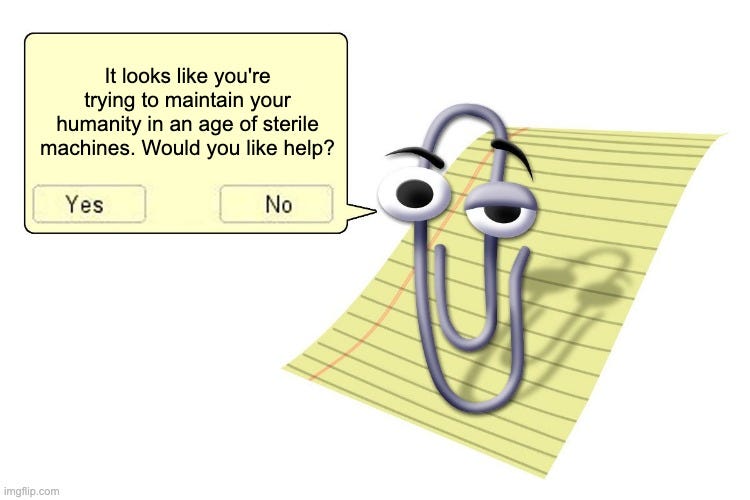

The greatest risk of AI is probably “we all get turned into paperclips,” or maybe “someone uses it to design a novel and incredibly fatal pathogen,” but the most certain risk — the one that’s already here, at least on the edges — is a great deskilling. Just as the mechanization of physical labor lost us all those traditional skills that Langlands describes, the ability to automate cognitive tasks undermines their acquisition in the first place. Why pay any attention at all to word choice and metaphor and prosody when ChatGPT can churn out that essay in a few seconds? Why worry about drafting a convincing email when you’re pretty sure your recipient is just going to ask Grok for a summary?4 Why learn to code when a machine can do it faster?

I was recently informed that someone — “not anyone you know, Mom, someone at another school” — used ChatGPT to write his essay about the causes of the Civil War. This was obviously deeply upsetting to the congenital rule-follower who reported it to me, on account of THAT’S CHEATING (you must imagine this in the whiniest she-touched-my-stuff voice possible), but it was a good teachable moment — for me, if not for the history teacher at another school. What’s the point of an essay about the causes of the Civil War, anyway? It can’t be that the teacher wants to know the answer: she can find a dozen books on the topic if she cares to look, each more cogent and thorough than anything a middle-schooler is likely to produce.5 Heck, even the Wikipedia article will probably give her a better understanding. And if it’s not for the teacher’s benefit, it’s certainly not for the benefit of any other audience, since as soon as the essay is marked and graded it’ll probably be crumpled up and tossed into the recycling bin. No, it’s for the kid.

The point of writing an essay about the causes of the Civil War is not to have an essay about the causes of the Civil War, it’s to undergo the internal changes effected by the process of thinking through, planning, drafting, and editing the darn thing. Writing forces you to put your thoughts in order, to shape whatever mass of inchoate ideas is bouncing around in your head into something clear and reasoned you can pin to the page. The thinking is the hard part; putting words to it is simple by comparison. (This book review began life as about seven hundred words of stream-of-consciousness riffing, with only the vaguest kind of structure. When I experimentally pasted it into an LLM and asked for an essay, the result was terrible.) But even the putting of words is a valuable skill: what’s the right tone here? What’s the right word? Do I want to say “writing forces you to” or “when you write you have to”? How do they feel different? Asking a machine to do this for you is like bringing a forklift to the gym.

Of course, that kid who had ChatGPT write his essay was almost certainly thinking of the assignment not as one small step in the alchemical process of self-transformation that is education but as basically equivalent to an appeal letter to the insurance company: just another dumb hoop you have to jump through in your interactions with a vast impersonal machine that doesn’t particularly want to grind you to dust but wouldn’t mind it either. And since this was at another school, he might not even be wrong. Maybe the teacher was just pasting the rubric and the essays back into ChatGPT and asking it to assign a grade.6

But there’s an even bigger problem than lying about who (or what) has done the work, which is lying about whether the work has been done at all. LLMs make lying very easy indeed. Yes, yes, sometimes they hallucinate and tell you things that are patently untrue, and that’s a bigger danger for students and other people who don’t have the background to notice when something seems off — this is all true, but it’s not what I mean.

LLMs, when working exactly as intended, enable human falsehood — because our society relies on written records as proof of work. Until recently that was fine, because writing down lies actually used to be pretty hard: putting together a convincing false report from scratch — maintenance records for the airplane you’re about to board, say, or a radiologist’s report on your brain scan — was almost as time-consuming as actually checking the things that were supposed to checked and then documenting them, and the liar had to spend the whole time aware of their own dishonesty. (Not that this stops everyone, of course.) But now that it takes about two clicks to generate an inspector’s report for the house you’re considering buying, or the pathologist’s findings in your biopsy, how much are you going to trust that they actually looked?

LLMs can be useful tools,7 but all tools change what we make and how we make it. It’s often a good tradeoff! Sure, each individual example of simplification and automation in the name of efficiency is a tiny bit of alienation, removing the maker from the making, but it’s also a gift of time we can spend on other things: I couldn’t write this if I also had to sew my family’s clothes and wash our laundry by hand. And yet those bits pile up, and once it becomes possible to exist in the world without really needing to come into contact with it, once you can get by without ever really needing to make anything, some people just won’t. And that’s terrible! Being entirely without cræft — never bringing mind-body-soul into harmony with one another and then using them to master the world — means missing out on something deeply human.

So assuming you’re not about to move to the backwoods and become a homesteading subsistence farmer, what’s the play? How do you inculcate in yourself and your children the habit of doing things the optional-but-hard way? How do you make people value a difficult but elegant solution instead just throwing more, MORE, MORE (money, stuff, compute) at the problem? Whatever it is, it has to be more than just repeating, to ourselves or others, that “it’s good for you.” (Alas, everyone in my house is unmoved by my claim that eating liver is a deeply human activity.) It has to be deep-seated and cultural, the kind of thing you do because, well, it’s just what you do.8

Something like this has happened with food. If you live in the industrialized world, it’s now entirely possible to get two thousand calories a day without ever engaging with the process of feeding yourself beyond buying things and putting them into your mouth. You don’t need to know a single thing about the plants and animals that became your dinner, let alone the processes that turned them from raw materials into a meal. And yet there are still parts of American culture that really value cræfty, optional-but-hard cooking. (In fact, I think cræft was the concept I was reaching toward back in this old review about cooking.) I don’t mean complicated dishes like Beef Wellington and other things the Psmiths call “cooking for people who don’t have babies,” either — just stuff like saving your bones for stock or making your own pie crust. People may say they do this because it tastes better (it does), or because it’s healthier (it is), or because it’s cheaper (yep, that too), but beneath all that there’s a sense that doing things from scratch is more honest, more real, than buying even the bougiest all-butter crust from Whole Foods. Of course it won’t be cræfty in the way preindustrial cookery had to be cræfty, because grocery stores and takeout still exist, but cooking from scratch is a lot closer than canned and frozen convenience foods or the ubiquitous burrito taxi.

Culture can make the technically optional feel mandatory. Sometimes that’s bad, but human creativity is good, and if we want to preserve it in an age of ubiquitous artificial generation then culture is our best hope. (And note, please, that this remains true no matter how good AI becomes; the question isn’t the quality of the output, it’s what depending on the output does to us.) I think it helps to make a point of doing other things you don’t really need to do — sewing, gardening, woodworking, recreational welding — just to drive home to yourself that you can, actually, exert your will on the world. And maybe spending your time reading and writing (and writing about reading, and reading about writing and talking about all of it), means you’ll raise a houseful of “wordies” who would no more dream of having ChatGPT write an email than I would dream of buying canned lentils.

Even as AI is letting us automate one kind of human making, though, it’s opening up a new one: making AI. Take, for example, the reaction earlier this year when the Chinese company DeepSeek dropped their V3 model: everyone in the AI world was amazed not because it performed a lot better than the top US LLMs, but because the team had built it so cheaply and efficiently. (DeepSeek claims to have trained the model for $6 million, compared to the $100 million OpenAI spent on GPT-4, and used about ten times less compute than Meta’s comparably-performing model.) They were operating on a shoestring, using intentionally crippled chips (the only ones allowed to be exported to China), and so they were forced by their constrained circumstances to discover and take advantage of facts about how GPUs work that no one in the US had noticed, because they didn’t have to. In other words, the DeepSeek team was cræfty.

We’ll always have some kind of scarcity (even if it’s just time or energy or “the amount of matter in the universe”), so on the bleeding edge there will always be room for the kind of human excellence that shines under scarcity and resource constraint.9 When you’re pushing the limits, there’s necessarily going to be alpha in understanding the world just a little bit better, in eking out just a little more performance from your materials. And every time we render something easy, we open up a new hard problem: the very technological advances that meant we no longer needed cræft for mere subsistence set in motion the conditions for those clever, elegant solutions from the Real Programmers at NASA and the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. The advances in chip technology and the high-level programming languages that mean you don’t need to worry about memory management created the conditions for massive systems that push scalability limits in other dimensions. And one day our descendants will be admiring the scrappy cræft of the men who built the first Dyson spheres, back before it got easy.

But the farther you get along the tech tree, the fewer people need to be cræfty — and the fewer people can. Every member of a hunter-gatherer band has to become intimately familiar with the landscape, the foodstuffs, the trees and rocks and weather. The same is true for the vast majority of a preindustrial agricultural society (though the number of different plants and animals you have to know shrinks with domestication). When some bright sparks started building watermills, they had to engage with wood and rock and physics in a way no one else had done yet, but everyone else could relax just a little. And then came the men with the steam engine and the internal combustion engine and the integrated circuit, and each time their cræft made life easier for everyone else — and the numbers of “everyone else” grew. Today we’ve pushed the bleeding edge out so far you have to be really very good to reach it, and the world is full of people who, no matter how hard they try, never will. What happens to them?

As in modern German and Dutch, Old English used the ge- prefix for past participles

For more on Old English cræft, especially in the Alfredian corpus, see here. Langlands quotes from the late Peter Clemoes, who wrote extensively on the topic, but no obliging Kazakh has put that online for me.

This is a fascinating word choice, because virtus is also a complicated and interesting word; it’s derived from the Latin word for man, vir, and means things like “force” but also “manliness” or “bravery” (like Greek ἀνδρεία). In the classical world, it came to mean something like moral worth or excellence in a particularly masculine way, and though it was adopted as a western Christian term for something like spiritual ἀρετή, it retained some of those echoes.

All the “AI written/AI read” communication begins to resemble Slavoj Zizek’s perfect date:

So my idea of a perfect date is the following one. We met. Then I put, she puts her plastic penis dildo into my…“stimulating training unit” is the name of this product. Into my plastic vagina. We plug them in and the machines are doing it for us. They’re buzzing in the background and I’m free to do whatever I want and she. We have a nice talk; we have tea; we talk about movies. What can be — we paid our superego full tribute. Machines are doing — now where would have been here a true romance. Let’s say I talk with a lady, with the lady because we really like each other. And, you know, when I’m pouring her tea or she to me quite by chance our hands touch. We go on touching. Maybe we even end up in bed. But it’s not the usual oppressive sex where you worry about performance. No, all that is taken care of by the stupid machines. That would be ideal sex for me today.

Well, okay, most of them.

See footnote four again.

Personally I’ve found them useful in three cases: (1) when I’m blanking on how to begin an email I will occasionally ask for a draft, which inevitably makes me so mad about how bad it is that I immediately rewrite it in a way that doesn’t suck; (2) when it’s Sunday night and I need a picture of a Japanese man in a business suit and a samurai helmet for a book review going up in the morning; and (3) when I can’t figure out the right search term for my question. (Turns out it was “sigmatic aorist.” Thanks, Claude.)

That’s it, that’s the definition of culture.

Assuming, of course, that there are still humans. (“Can AI be cræfty” - the greatest thread in the history of forums, locked by a moderator after…)

A friend once laughed at me for making my kids cardboard swords when she could click a button and have half-a-dozen brightly colored foam swords mailed to her for about $6. I didn't answer the real reason: I want my kids to realize that they can interact with their world and make things out of things. There's a certain empowerment to realizing that you can make things, not just buy them. That said, our work is sub-par compared to both industrialized products and the handiwork of actual craftsmen. The thing about *good* crafting is that it requires tools. Tools require workshop space. We don't have that. It also requires time to fiddle around and try things, something that seems awfully scarce in our post-industrial, dual-income, private-school lives. Needless to say, I follow homesteaders on IG and would be thrilled to read a book about craeft.

Consistently one of my favorite Substacks - and this was no exception! Great review