REVIEW: The Wizard and the Prophet, by Charles C. Mann

The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World, Charles C. Mann (Picador, 2018).

There used to be famines.

Poor harvests and crop failures have been with us since the development of agriculture: archaeological evidence makes it clear that farmers have always lived on the knife’s edge of subsistence, often hungry or malnourished, and from there it doesn’t take much to push them over the edge into famine. Too much rain or not enough, volcanic ash that chokes out the sunlight, diseases that affect the staple crops or the draft animals and peasants needed to bring them in from the fields, even wars that displace farmers and intentionally ravage agricultural land. If it’s just you and your neighbors, you can go where there’s food. If it’s just your province, you can import food from elsewhere. But really large-scale events (and/or really constrained trade networks) mean there’s nowhere to get food from, nor enough surplus to make it available at any sort of affordable price.

And when the malnourished survivors of one bad year confront the trials of the next growing season, well, these things have a way of snowballing. We all know, for instance, that the Black Death (1347-1351) killed a third to a half of the population of Europe, but how many people remember that Y. pestis arrived in a continent already weakened and destabilized by the Great Famine (1315-1317), which had killed as many as 15% of the people — and 80% of the livestock?

Crops still fail today: we haven’t eliminated drought or rain or swarms of hungry locusts. But by the end of the twentieth century, famine proper (as opposed to malnutrition and “food insecurity”) existed only when someone created it on purpose by preventing food from getting to hungry people.1 There is simply so much surplus that there’s more than enough food to go around, and our supply chains are so extensive that it can go around. Imagine telling a medieval peasant that nowadays poor people are far more likely to be fat than hungry! What hunger remains today is mostly a product of corruption, incompetence, or outright theft, and it almost never involves millions upon millions of corpses.

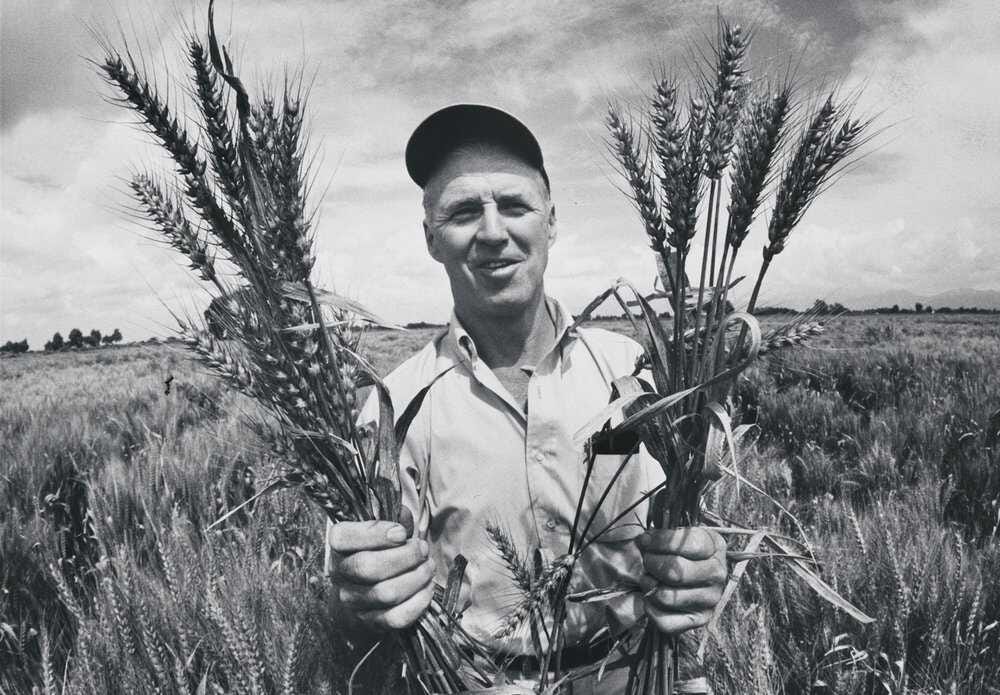

For this tremendous triumph of human technology and ingenuity, we mostly have Norman Borlaug to thank.

Borlaug was the father of the Green Revolution, an Iowa farmboy who escaped what he called the “endless drudgery” of subsistence agriculture into an academic career in plant pathology. His main work was in battling fungal blights like stem rust, which regularly destroyed entire harvests, and in 1944, the Rockefeller Foundation sent him to a desperately impoverished region of Mexico with a mandate to develop rust-resistant varieties of wheat. The work was almost literally back-breaking — lacking draft animals or a tractor, Borlaug and his assistants had to pull their own plow and plant more than 110,000 wheat plants by hand, then go back and cull any plant that showed signs of rust — but it wasn’t enough: the Bajío, the central Mexican lowland where he had been assigned to work, had such poor soil that progress was incredibly slow. So Borlaug hit on an audacious but counter-intuitive idea: he would painstakingly cross-pollinate the most promising rust-resistant wheat strains, then fly the seed to the sunny, fertile, and well-irrigated Sonora, which had a different growing season. Whatever promising seed he harvested in Sonora would be flown back to the Bajío and the process repeated, to develop hybrid strains of wheat twice as fast.

It was an unbelievable amount of work, and lacking any detailed knowledge of plant genetics it also required enormous scale — tens of thousands of crosses, year after year — and a hefty dose of luck to combine only the various desirable traits. Borlaug’s wheat was supposed to resist rust, of course, but he also needed it to be highly productive, insensitive to day length so it could grow at any latitude,2 and to make excellent flour. Also, he quickly realized that it needed to be short: the massive heads of grain from his super-productive strains were so heavy that a single gust of wind could permanently damage the stems. All of these traits existed independently at different places in the plant’s genome, but many were actually competitive disadvantages without the others. A heavy seed-head would make the stem break before it matured, but a plant with short straws would suffer in the shade of its taller neighbors; you needed both to make either practical. (Short straws are also more energy-efficient, from the human perspective, since more of the plant’s energy can go to producing grain vs. inedible straw, but they’re much harder to reap by hand — a modern wheatfield looks very different from what you might have seen in paintings and requires machinery to harvest effectively.)

In the end it took two decades, but Borlaug (and what was by now a sizeable team) produced an all-purpose wheat that could be grown almost anywhere in the world. As long as it had enough water and fertilizer, it would produce more grain than ever before: Mexican farmers went from reaping about 760 pounds of wheat from every acre to almost 2,500 pounds from the same land. Similar projects ensued for maize and rice.

Norman Borlaug is generally estimated to have saved the lives of about a billion people who would otherwise have starved to death.

Yet despite all this — and Borlaug’s is a great story, which Charles Mann tells better and in far more detail than I do above — his book isn’t really a biography of Borlaug or of its other framing figure, early environmentalist William Vogt.3 Rather, it’s a compellingly-written and frankly fascinating overview of various environmental issues facing humanity, and of two different sorts of approaches one can take to addressing them. Mann opens by introducing the two men, but as soon as he’s done that they function mostly as symbols, examples and stand-ins, for these two schools of thought about the world and its problems.

Borlaug is the Wizard of the title, the avatar of techno-optimism: with hard work and clever application of scientific knowledge, we can innovate our way out of our problems. Vogt is the Prophet, the advocate of caution: he points to our limitations, all the things we don’t know and the complex systems we shouldn’t disturb, warning that our constraints are inescapable — but also, quietly, that they are in some sense good.

It’s not hard to identify the Wizards all around us. Inventors and innovators, transhumanists and e/acc, self-driving cars and self-healing concrete…every new device or technique for solving some human problem — insulin pumps! heck, synthetic insulin at all! — is a Wizardly project.

It’s a little more difficult to pin down what exactly the Prophets believe, in part because they spend so much time criticizing Wizardly schemes as dangerous or impractical that it’s easy to take them for small-souled enemies of human achievement.4 That isn’t fair, though — there’s a there there, a holistic vision of the world as an integral organic unity that we disturb at our peril, because the constraints are inextricably linked to the good stuff.

If that seems too abstract, here’s an example. Imagine for a moment (or maybe you don’t have to imagine) that you have a friend who subsists entirely on Soylent. It’s faster and easier than cooking, he says, and cheaper than eating out. He’s getting all his caloric needs met. And he’s freed up so much time for everything else! Now, anyone might express concern for his physical health: does Soylent actually have the right balance of macronutrients to nourish him? Is he missing some important vitamins or other micronutrients that a normal diet might provide? Is the lack of chewing going to make his jaw muscles atrophy? And those are all reasonable concerns about your friend’s plan, but they all have possible Wizardly solutions. (A multivitamin and some gum would be a start.)

If you’re a Prophet sort, on the other hand, you’re probably going to start talking about everything else your friend is missing out on. There’s the taste of food, for one, but also the pleasures of color and texture and scent, the connection to the natural world, the role of community and tradition in shared meals, the way cooking focuses thought and attention on incarnate reality. You might throw around words like “lame” and “artificial” and “sterile” and “inhuman.” Your friend’s Soylent-only plan assumes that the whole point of food is to consume an appropriate number of calories as quickly and easily as possible, hopefully in a way that doesn’t meaningfully degrade his health, but a Prophet rejects his premise entirely. Instead, a Prophet argues that your friend’s food “problem” is actually part of the richly textured beauty of Creation. Yes, feeding yourself and your loved ones delicious, healthful, and economical meals takes time and effort, but that’s simply part of being human.5 You should consider that a challenge to be met rather than a threat to be avoided.

Unfortunately, Mann does the Prophets a disservice by choosing William Vogt as their exemplar. Yes, he was an important figure in the history of the modern environmental movement. Yes, he wrote a very influential book.6 And yes, his careful attention to the integrity of the ecosystems he studied was quintessentially Prophet. But he saw human beings mostly as disruptions to the integrity of those ecosystems, and pretty much every one of his specific predictions — not to mention the predictions of his many followers, most famously Paul Erlich in The Population Bomb7 — have simply failed to come true. Compared to Borlaug’s obvious successes, Vogt’s dire warnings that humanity will soon exhaust the Earth’s capacity and doom ourselves to extinction (unless we abort and contracept our way there first; his second act was as director of Planned Parenthood) seem laughable. Reading about his life can leave you with the impression that Prophets are just people who are more worried about a spotted owl than a starving child, and frankly who cares what those people think?

More illuminating, I think, is to look at the solutions Prophets actually propose. Luckily, Mann helpfully dedicates the meat of his book to comparing Wizards’ and Prophets’ approaches to various environmental issues. Faced with the struggle to feed a growing population, for example, contemporary Wizards are trying to genetically engineer food crops to perform photosynthesis more efficiently.8 Prophets, by contrast, are working on projects to domesticate wild perennial grasses, which have much deeper roots and require less water and fertilizer than annual crops,9 or to encourage switching from cereal-heavy industrial agriculture to the cultivation of tubers and tree crops, which can produce many more calories per acre than grain. (Grain, of course, has other advantages.)

Or take water. Wizards are behind massive technological and engineering accomplishments like Israel’s National Water Carrier and giant desalinization plants that use reverse osmosis to turn seawater into freshwater. Prophets suggest things like “don’t have a lawn in Tucson, Arizona” and “patch the leaks that make towns in KwaZulu-Natal lose more than a third of their freshwater supply before it even gets to the tap” and “maybe pumping the entire Colorado River into California’s Central Valley so almond farmers can flood their fields with two inches of water that literally evaporate before your eyes is a bad idea.” They’ve also done some cool projects, like shortcutting around tertiary wastewater treatment by pumping Tel Aviv’s treated sewage onto nearby sand dunes, where it’s slowly purified by filtering down through the sand, recharges the coastal aquifer, and can be used to irrigate the Negev.

Or consider atmospheric carbon dioxide. Wizards have proposed massive projects like capturing the carbon dioxide produced from burning coal, or more limited — but possibly more effective — ones like releasing sulfur dioxide and other aerosols into the stratosphere to counteract the warming effect of CO2. Prophets advocate things like reforesting the Sahel, or even one day the Sahara, and letting the trees do the carbon capture for us. (Then we can turn the trees into charcoal, which keeps most of the carbon trapped, and bury the charcoal to enrich poor desert soils, in which we can plant more trees...)

You can begin to see what all these Prophet schemes have in common: as much as possible, they piggyback on existing natural processes. There are a couple of reasons for this: one, of course, is a very real concern that disrupting complex systems will lead to snowballing unintended consequences. After all, this is true even of Borlaug’s lifesaving Green Revolution grains: to realize their full potential, they need lots of water (which can mean drained aquifers or soil salinization if the irrigation is done poorly) and lots of fertilizer (which washes into lakes and oceans to produce substantial aquatic dead zones). But beyond practical caution, Prophets are driven by a genuine fondness for the integrity, stability, and beauty of those complex systems — including their human parts. Something really is lost, they say, when when our contact area with the world shrinks. We understand less, we experience less, and we ultimately become less human.

To give Mann his due, though, you can also begin to see why he used Vogt as the symbol of the Prophets: there’s not really a better option. There is — there can be — no Borlaug equivalent, because Prophet solutions don’t scale. They are necessarily local and particular, because they have to build off the way things already work and so suit themselves to the character of the people and landscape wherever they’re proposed. You can build a desalinization plant on any coastline anywhere in the world, but you can only filter your wastewater through sand dunes if you’re in Tel Aviv.10 Reforestation looks different in Burkina Faso than it does in Ethiopia, for both cultural and climate reasons. And this obviously poses a huge problem for the bureaucracies that have embraced Vogt’s apocalyptic message — if we don’t change what we’re doing, and soon, we’re all going to die! — because executing local and particular solutions require actually knowing things.

Even in the best case, executing Prophet plans — exploiting the workings of a complicated, opaque system full of unseen feedback loops — requires a lot of very specific process knowledge of a sort that doesn’t translate easily into books…or grant applications. Now, I’m told that there do exist government officials with actual domain-specific expertise, or at least the good judgment and freedom of action to recognize and empower the people who do have it. (After all, the Israelis made that wastewater thing work!) But unfortunately, the slow-moving, sclerotic meritocracies of our regulatory/NGO complex aren’t staffed by those people.11 Pretty much all they can do is eat hot chips and lie fund highly legible projects and ban things.

Take, for example, the 15-minute city, which is a radical proposal that people should be able to get pretty much anywhere they need to go within fifteen minutes and ideally without needing a car. It’s a lovely idea, and the parts of residential America that are like that — most of them former suburbs — are insanely desirable and therefore insanely expensive. If it were easy to make more of them, you’d think the market would have figured out how! And if I had any confidence whatsoever that anyone involved in municipal planning could produce more neighborhoods like that — leafy green places full of parks, libraries, schools, and shops — or even that they wanted to have safe, clean, and reliable transit options, I’d be all for it. But these are the same people who are gutting public safety in the cities while failing to maintain or enforce order on existing transit. These are the same people who imposed draconian Covid mitigation policies like Zoom kindergarten, padlocked churches, and old people dying alone with nothing but a glove full of warm water to mimic human touch, all of which were meant to buy time for…something (human challenge trials? nationalized N95 production?) that never happened. It’s easy to ban things; it’s hard to do things. So you’ll excuse my doubts about their ability to build a 15-minute city that looks like Jane Jacobs’s ideal mixed-use development, with safe, orderly streets and a neighborhood feel. One rather suspects they would find it far more within their wheelhouse to simply abolish single-family zoning or imposing restrictions on who can go where, when.

Much of our elite has adopted the Prophets’ rhetoric — scale back! consume less! protect biodiversity! — without actually knowing anything about how complex systems work or considering that humans are part of them. This is poison, because it means their proposals combine the worst of the Wizards’ approach (abstract, context-insensitive, casually destructive of a dozen other parts of the complicated interconnected systems they innovate on) and the worst of the Prophets’ (zero-sum, labor-intensive, willing to sacrifice freedom and prosperity in the interests of some other goal). Sometimes it makes sense to take the Wizards’ path even knowing you’re losing something because you have so much to gain, and sometimes it makes sense to take the Prophets’ way even if it means hard work and a simpler or less prosperous life because, again, there’s something else to gain. (This is the logic of a mother devoting herself to the home and family.) But it only makes sense to take the Prophets’ way when you have a vision of what’s good about it, of why it matters: after all, there are people who live in the pod and eat the bugs, who own nothing and are happy. And we call these people monks.

Look, I don’t really have a lesson here about whether the Wizards or the Prophets are “right.” For some problems, you should obviously be a Wizard: human technological innovation, our conquest of brute Nature, has brought us unprecedented levels of health, longevity, and leisure with which we can accomplish great things. In other cases, you should just as obviously be a Prophet: trying to engineer away the actually-existing order of the world in the interests of some scalable “solution” often destroys the conditions for human flourishing. Instead, the most valuable part is the dichotomy itself. Now, I say this partly because I am an inveterate categorizer,12 but it really is incredibly useful: Wizard vs. Prophet doesn’t quite map neatly to any of the other ways we’re used to dividing the world, and you can apply it not just to environmental issues but to pretty much any aspect of human life.

The most obvious examples are ones that involve literal technology, in the sense of shiny machines, where you rapidly notice that many people feel about the human body pretty much the way the pioneers of “organic” felt about the soil. As should be predictable by now, many of the Prophets’ objections are couched in the Wizards’ own terms: critics of transgenderism, for example, often talk about the unsatisfactory outcomes of genital surgery, but this is basically a “what about the micronutrients?” response to the Soylent-only diet, true but not the real objection. No one saying “a man can’t turn into a woman” would actually change their mind if advances in biotech produced a more convincing result! The fundamental disagreement is one about the nature of reality, which inevitably involves a conflict over values. The same is true of conversations about artificial wombs — sure, we can discuss whether it’s possible for them to work as well as the old-fashioned kind, but even if they did there would still be objections on the grounds of what it means to be human — or IVF and embryo screening, or torturous efforts to delay death a little longer. In each case, the Wizards are excited to improve the human condition by ameliorating suffering, and the Prophets accuse them of having such an impoverished view of humanity that they would sacrifice something vital in the process.

But it goes even farther, because if you zoom out a little more, if you tilt your head to one side, then you realize that there can also be Wizards and Prophets with respect to social technology. As with the soil and the human body, society’s norms and institutions are the sort of thing that some people regard as fertile ground for innovation and improvement and others see as a moral order that should not be disturbed, both because it would be imprudent and because it would destroy something of real value. It may seem a little funny to cast the Prophets as small-c conservatives, because our contemporary discourse usually associates environmentalism and a Prophet take on the natural world with the political left, but what else is the massive social shift of the last fifty years but the consequences of a Wizardly project to engineer and innovate our way to greater prosperity?

A few of the people reading this may be thorough-going Wizards in every walk of life, embracing everything from genetically-modified crops to meal replacement drinks to artificial wombs to polyamory, but most of us are Wizards about some things and Prophets about others. The trick, I think — or perhaps the challenge — is to think carefully about what the real tradeoffs are with technological innovation, and whether there’s a way to hang onto some of the good things the Prophets see while still capturing some of the good things the Wizards offer. The problem is that it’s often impossible to hang onto old ways of doing things when no one else around you does.

Jon Askonas has written beautifully about this more broadly, but as a toy example let’s consider dating. I got the last chopper out of ‘Nam, but from talking to my single friends reading Twitter extensive sociological research, it’s clear that dating apps have become so ubiquitous that norms have shifted. It’s now “creepy” and “weird” and “offputting” to express romantic interest in any context not explicitly marked out for it. No one likes the apps, they’re demonstrably a terrible way of finding a spouse, but they’re so thoroughly entrenched that if you try to defect and flirt (or, God forbid, ask someone out) at work or church or your friend’s barbecue, you send up all sorts of “weirdo who does not respect social norms” red flags even if you two would probably have gotten along.

And now consider all the other technological changes humans have made and the ways they’ve changed the way we live. It’s really no surprise that the idea of dehumanization, that it’s possible to be human but live a less-than-human life, first arises in the eighteenth century.

Once you’re looking for Wizards and Prophets, they show up all over the place — including in a surprising number of our book reviews. John was dissatisfied with Vaclav Smil because the first half of his book was spent praising the successes of premodern Wizards and the second half being a modern Prophet. James C. Scott offers the ur-Prophet history13 where the terrible Wizardly mistake that doomed us to a less-than-human life was, uh, agriculture. And Akenfield is a bittersweet portrait of the conflict between what the two approaches to the natural world can bring us: prosperity, on the one hand; meaning, on the other. But the tension between innovation and tradition, the question of what we lose when we gain something else and how we make those choices, lurks quietly behind a great deal of what we write. (Then again, I am dispositionally far more of a Prophet than my husband — probably because I’m a woman! — so of course I see this question everywhere.)

But then again, Prophets are everywhere, and not just among the hippies. The King (yes, of England) is one, and not in the soulless neoliberal Great Reset kind of way: he has written of his abhorrence of “pettifogging rules and regulations that suck out the character, charm, and spiritual meaning from every pore of our human experience” and accordingly he’s sponsored the design and construction of a new village built according to traditional principles, founded a school of traditional arts, and has the meadow at his estate at Highgrove mowed with scythes. The entire Arts and Crafts movement and their modern descendants were Prophets, and so are the people who like grass-fed beef because it lets the cows be cows. (The people who like it for health reasons14 have adopted the Prophets’ positive claims about complicated systems and feedback loops and the limitations on our ability to design, even if they haven’t wholesale assumed the worldview.)

And sure, part of the growing popularity of Prophet-style “crunchiness” is probably just that the more we learn about biological systems, the more we realize that they resist a naively mechanistic approach. But it’s not an accident that the first advocates for composting over synthetic nitrogen were British aristocrats, and I didn’t just tell you that trivia about King Charles because I find it delightful: it really is easier to make small material sacrifices in the pursuit of particularity and the organic unity of the world when you’re the King. Or when, thanks to the innovations of the Wizards, you live like one.

This is a powerful weapon of war. Sometimes the victims were already hungry because of natural disasters, like the drought and locust swarms of northern Ethiopia, and sometimes because their enemies intentionally destroyed their capacity for food production, as in Yemen, but either way intentionally preventing imported food from making it to your hungry enemy is a good way of hurting them and about the only reason anyone starves to death any more.

You may recall Jared Diamond’s suggestion, in Guns, Germs, and Steel, that agriculture was slower to diffuse across the Americas than across Eurasia because most plants respond to day length and won’t grow properly much north or south of their original homes. Borlaug’s Bajío-to-Sonora plan only worked because he had randomly lucked into a photoperiod-insensitive mutant strain of wheat.

They were roughly contemporaries, but this is emphatically not the story of a pair of rivals; they encountered each other in person only once, in passing, after which Vogt wrote an angry letter to the Rockefeller Foundation demanding they cease Borlaug’s Mexican project at once.

And, to be fair, a lot of the language and arguments pioneered by Prophets does get employed by a sclerotic managerial class opposed to anything they can’t fit neatly into their systems and processes and domain-agnostic expertise. But more on that later.

Incidentally, this is more or less the argument between the Wizards and the Prophets when it comes to soil. Wizards are delighted with the Haber-Bosch process and artificial fertilizers; Prophets decry the “NPK mentality” that sees the soil as a passive reservoir of chemicals and instead laud composting, manure, and other techniques that encourage the complex interactions between soil organisms, plant roots, and the physical characteristics of humus. This is the origin of the fad for “organic,” a label that doesn’t mean much when applied to industrial-scale food production and is often more trouble than it’s worth for small-time farmers and ranchers. Still, Mann’s story of the movement’s birth is interesting.

You’ve probably never heard of it, but it was influential!

Apparently out of print! Good.

Photosynthesis is actually a shockingly inefficient process: most plants manage to use only about 0.5% of the available energy from sunlight. A few, however, have a somewhat more efficient version of the process — specifically, they do the carbon fixation part better — and one or two even combine the two versions in different parts of the same plant, which suggests that the genetic pathways have some similarities. Mann explains this all very well but at far more length than I have here, so I do encourage you to check out the book or at least the Wikipedia article on C4 carbon fixation.

This project is the source of that famous picture of roots.

There are probably other cities (Las Vegas comes to mind) that are close enough to sand dunes for this to be a practical option, but the point is that you need a lot more different things to be just right to copy any given Prophet approach than you do to imitate a Wizard scheme.

Or possibly worse, they’re set up so that those people can’t do anything.

Ask me about my Enneagram type and my color season!

Pun intended.

You know who I mean: the people who cook with tallow and cast iron instead of canola oil and Teflon. There are dozens of us!

An excellent review of an excellent book!

Beautifully written. Halfway through I got the idea that "Wizards" and "Prophets" can be used as stand-in terms for "Progressive" and "Conservative". Progressive people want to push the envelope, abhor rules they deem archaic and in general just want to change the status quo, whereas conservative people are cautious and think hard about how a change in status quo can have negative effects - they in effect gatekeep the most ludicrous ideas. We really need both to advance in a manner that will harm us least. This see-saw seems ineffective, but in reality has built the societies with the highest quality of life on planet earth. It goes without saying that a democratic society with free spech is a requirement for this to work - there has to be a fair marketplace of ideas and the possibility to change course via elections.