REVIEW: A Means to Freedom, by H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard

A Means to Freedom: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard 1930-1932 (eds. S.T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, and Rusty Burke; Hippocampus Press, 2017).

In my review of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories I mentioned his two-volume collected correspondence with H.P. Lovecraft, for which I of course was not going to shell out the $60.

Well, it probably surprises no one that I of course did shell out the $60.1 And I’m so glad I did, because it’s delightful!

If you’ve read H.P. Lovecraft’s story “The Rats in the Walls,” you may remember the bit of Gaelic at its dramatic conclusion. (If you haven’t read the story, please follow that link and read it immediately, it’s better than anything you’ll find on this Substack.)2 But finding Gaelic there is odd, because the story is set in southern England where you might more reasonably expect to find a Brythonic language (probably Welsh) than Gaelic, spoken in Scotland and Ireland. Back when Weird Tales originally published the story in 1924, no one noted the incongruity. When it was reprinted in June 1930, however, Celtic linguistics nerd Robert E. Howard was on the case.

Howard hadn’t yet created Conan, but he was already a regular Weird Tales contributor, so naturally he wrote to WT editor Farnsworth Wright. That letter begins with the remark that “I note from the fact that Mr. Lovecraft has his character speaking Gaelic instead of Cymric, in denoting the Age of the Druids, that he holds to Lhuyd’s theory as to the settling of Britain by the Celts” and goes on to explain Howard’s own theories on the topic. At length.3 Poor Wright — who was trying to run a magazine, suffering from Parkinson’s disease, and probably had very little interest in Insular Celtic linguistics to begin with — did the obvious thing: he forwarded the letter to Lovecraft. Lovecraft, in turn, wrote back to Howard and admitted that the Gaelic phrases had actually been cribbed wholesale from Fiona MacLeod’s “The Sin-Eater” and should not, alas, be taken as an indication of any particular stance on the debates about the prehistoric peopling of the British Isles.

Unfortunately, Lovecraft’s letter doesn’t survive. (In lamentable fact, a fair portion of Lovecraft’s side of their exchange is missing; Howard’s father accidentally destroyed the originals in the 1940s and we are left with only the transcripts Arkham House had already created for their five volume Selected Letters before that date.) A Means to Freedom, then, really kicks off with Howard’s response. That particular letter is actually a bit skimmable, since we now know quite a lot more about than we used to about historical migrations, but the massed effect is that of sheer joy at having been noticed by the Great Man and an intense desire to impress.

“I say, in all sincerity, that no writer, past or modern, has equalled you in the realm of bizarre fiction,” Howard writes, and, “neither [Poe nor Machen] ever reached the heights of cosmic horror or opened such new, strange paths of imagination as you have done…” And then he presents six typed pages of argument and extended scholarly quotations to bolster his case that the Cymric-speaking peoples preceded the Gaels in Britain (he’s right, by the way), followed by a slightly sheepish sort of apology for his wall of text and the hope that “you will have the time and inclination to write me again when it is convenient for you.” It worked: Lovecraft wrote back that “[y]our observations on Celtic philology & pre-history proved immensely fascinating to me…my own vague smattering sinks into total negligibility beside the array of facts & reasonable deductions at your command,” and asked Howard’s opinion on some of his own lengthy crackpot theories about the historical bases for the Fomorians, Milesians, and Tuatha De Danann.

From that point on their correspondence became quite regular, running to 900 densely-set pages composed over just under six years. (Howard killed himself in June of 1936.) They’re both excellent writers, of course, and though they never met in person it’s a pleasure to watch their acquaintance blossom into real friendship. It’s also surprisingly familiar: anyone who’s ever made a friend online will recognize the dynamic. First the semi-professional remark on topics of mutual interest, then the increasing chattiness, the gradual sharing of personal details, the growing warmth, the introductions to third parties your new friend might like. (Also, the letters are peppered with little asides like “by the way, what is your opinion about the origin of the Hittites?” which is 100% a thing that happens in my DMs.) They’re forever sending each other postcards and photographs and articles of interest, and it’s so reminiscent of dropping a photo or a link in the group chat that it’s almost jarring when they mention that some manuscript should be returned eventually or that “you should feel free to keep it for your records” and you recall that these are real physical objects traveling through the actual mail.

But one of their major topics of discussion is pretty different from ours: they’re forever telling each other about where they live. This is not a feature that marks much of my correspondence — my friends and I talk about our struggles, our children, our struggles with our children, but not much about what our neighborhoods, towns, or regions are like. Partly, I think, this is because nowadays we all live the same place (online).4 Partly it’s because film, television, and Instagram have given us the impression that we know other parts of the world: I have a pretty good idea of what New Mexico, Delhi, or Brooklyn look like, despite never having actually visited any of them. Partly it’s because many of us live in places that don’t really have much about them that’s unique or special: my suburban strip mall and your suburban strip mall may at least have different kinds of cheap ethnic restaurants, but every one of our big, hip cities has exactly the same WeWork and Soulcycle and Sweetgreen. If I tell you I’m going to grab a latte at the independent coffee shop down the street, it doesn’t matter whether I live in Provo or Pascagoula or Poughkeepsie: you already know exactly what it looks like, right down to the reclaimed wood tables, exposed brick and pipework, and the water bowl outside for all the heckin’ puppers. Even the nightclubs are the same!

And of course, as this spreading gray sameness eats up America’s cities and suburbs, we’re also moving between them. It’s hard to see past the Target parking lot (or the high rise building with a first-floor Cava if you’re cooler than me) to say much about the fundamental nature of a place you’ve only lived for a few years. At least if you layer decades of personal and familial memory, you can distinguish between the Starbucks in the big box development that used to be a peach orchard and the Starbucks in the downtown building that used to be a soda fountain. The condition Lovecraft describes here is simply no longer the case, in either direction:

Really, each average American is a citizen of his own section alone in the fullest sense. Of the whole fabric, he knows the political externals and high spots as textbooks and casual reading have sketched them; but his knowledge of intimate details, folkways, sources, backgrounds, and deep cultural trends is generally confined to the vaguely-bonded subdivisional unit in which he grows up—or at least, to that unit and the spatially and chronologically contiguous units which have shared its fortunes in the historic stream.

Still, there really are differences even between my town and the one twenty minutes away — let alone different parts of the country. I wish I knew more about where my friends live. What are the trees like? How does it smell after the rain? Is the landscape flat and open or bunched up like a wrinkled quilt? Are the houses cozily clustered next to the street or set back amid imposing lawns? Tell me about the architecture!

Here’s Howard trying to convey something of Texas to his New England pen pal. I’m just going to give you a taste, but I promise there are pages of this stuff:

In the hundred mile stretch from Sonora to Del Rio on the Border, there’s not even a cluster of Mexican huts to mar the scenery and there’s just one store, a sort of half-way place. The rest is just—landscape! Wild, bare hills, with no grass, no trees, not even mesquite; not even cactus will grow there—only a sort of plant like a magnified Spanish dagger, called—I believe—sotol.

And I have an idea that the plains south of Llano Estacado are more or less wide-open. A land boom flopped there quite a number of years ago and the railroad to the town where I lived a while was discontinued. I was very young and my memories are scanty; but I remember illimitable plains stretching on forever in every direction, sandy, drab plains with never a tree, only tuffs of colorless bushes, haunted by tarantulas and rattlesnakes, buzzards and prairie dogs; long-horn cattle, driven in to town for shipping, stampeding past the yard where I played; and screeching dust winds that blew for days, filling the air with such a haze of stinging sand that you could only see for a few yards.

It’s clear from Howard’s references that Lovecraft wrote him plenty of letters describing Rhode Island, but most of them are lost; Lovecraft had an incredibly wide correspondence, loved to talk about his homeland, and probably waxed slightly more lyrical to someone else, so Arkham House never bothered reprinting the ones sent to Howard.5 Here’s a bit he wrote about New England more broadly:

These rows of buildings on a winding grey road, with stone-walled rocky pastures undulating off to the edge of a forest, and hillside apple orchards with gnarled boughs rising in the rear, present about as perfect a picture of a long-settled countryside as anything in North America. The structures fit the landscape so well—and both are so unique and distinctive and graceful—that artists never tire of painting the idyllic ensemble. Add to these things a background of tall ancient elms, an old mill by a reedy stream, and a vista of a distant valley where the massed foliage is pierced by the roofs of a village with characteristic white-steepled New England church, and you get an impression of stable antiquity and tranquil beauty not excelled by anything else this continent has to offer. … Also, the New England topography with its rolling terrain, picturesque rocks, splendid trees, and exquisite rivers and valleys, is absolutely unapproachable from a scenic standpoint. In Southern New England the landscapes are beautiful in a gentle way; but in Vermont and New Hampshire the presence of mountains adds a kind of weird grandeur. The ancient seacoast, with old ports and wharves, and memories of whaling and East-India trade, has a flavour all its own… Yes—New England is a great old country, with 300 years of continuous settled life behind it; and it'll take the machines and the foreigners a long time to tear the whole of it down!

Howard is similarly elegiac about the frontier:

Well, they have gone into the night, a vast and silent caravan, with their buckskins and their boots, their spurs and their long rifles, their waggons and their mustangs, their wars and their loves, their brutalities and their chivalries; they have gone to join their old rivals, the wolf, the panther and the Indian, and only a crumbling ‘dobe wall, a fading trail, the breath of an old song, remain to mark the roads they travelled. But sometimes when the night wind whispers forgotten tales through the mesquite and the chapparal, it is easy to imagine that once again the tall grass bends to the tread of a ghostly caravan, that the breeze bears the jingle of stirrup and bridle-chain, and that spectral camp-fires are winking far out on the plains.

They return again and again to the differences between Texas and New England. I suppose if they were writing today they might compare Shaw’s and HEB, but a hundred years ago they could compare the countryside to the unsettled frontier: “[t]he very essence of a real civilisation,” Lovecraft writes, “is the continuous dwelling of generations on the same soil in the same manner.” And Howard agrees:

[New England and the South] had the advantages of a settled and mature cultural civilization before the rise of the present machine-ruled age. You had a period of cultural development during which your ships plied the high seas bring in the wealth of foreign ports, and the arts of poetry, literature, architecture, and so on, acquired solid foundation and had the opportunity to flourish and bloom. … The Southwest and the West on the other hand, have never had the time to develope a cultural civilization of their own. The transition from primitive pioneering times to the machine age is almost unbroken. Westerners have no had and will not have time to develope any real civilization, founded on cultural ideals and principles, before the rise of the mechanized epoch.

For a very practical illustration of what they mean, check out the variety in this selection of stone walls. New England’s rocky soil, its complicated geological history, and its relatively early settlement all mean that fieldstone masonry was widespread but techniques and raw materials were intensely local. In some places, you can judge your location within a few miles just by looking at the walls.

In Texas, on the other hand, they used barbed wire.

I originally grabbed these books because the introductory material in the Del Ray “Conan” editions kept quoting from Howard’s letters about barbarians, and barbarism is a topic of perennial interest to…well, us, anyway. The back cover blurb of this first volume promises that Howard’s correspondence with Lovecraft eventually develops from discussion of history more generally into “a complex dispute over the respective virtues of barbarism and civilisation, the frontier and settled life, and the physical and the mental.”

This is a lie.

This finally dawned on me about three hundred and fifty pages in, at which point I was a little annoyed. Oh, sure, they talk about it, but “dispute” is entirely the wrong word: there’s none of the argumentation, debate, or weighing of pros and cons that implies. (Marketing material misleads, film at 11.) On reflection, though, I think that’s just as well: their treatment of human populations, for example, is taken more or less directly from Gobineau and Madison Grant and is thus much less interesting than it could be because we know it’s not, uh, true. Any debate about human civilization based on similarly flawed facts would have been equally skimmable, just like all the Enlightenment political philosophy that claims to extrapolate facts about human nature from the condition of the Americas less than a century after their wholesale depopulation due to epidemic disease.6

The actual conversation they did have is great fun, though, because it’s really just a discussion of vibes, beautifully presented by masters of weird literature: you get a tour of each man’s imaginative landscape as compelling and satisfying as their descriptions of their physical surroundings.

It begins with a letter from Lovecraft, now lost, in which he describes what the excellent annotations call his “famous Roman dream.” Another version of this dream, which he sent to Donald Wandrei, would be printed in 1940 as “The Very Old Folk,” and presumably what Lovecraft sent Howard was much the same: the tale of a strange dream in which Lovecraft found himself the Roman quaestor L. Cælius Rufus, confronted with hideous antique practices in the rural hills of Hispania Citerior.

Howard wrote back that he suspected dreams contained some sort of ancestral memories:

I have lived in the Southwest all my life yet most of my dreams are laid in cold, giant lands of icy wastes and gloomy skies, and of wild, wind swept fens and wildernesses over which sweep great sea-winds… I am never, in these dreams of ancient times, a civilized man. Always I am the barbarian, the skin-clad, tousle-haired, light eyed wild man, armed with a rude axe or sword, fighting the elements and wild beasts, or grappling with armored hosts marching with the tread of civilized discipline, from fallow fruitful lands and walled cities. This is reflected in my writings, too, for when I begin a tale of old times, I always find myself instinctively arrayed on the side of the barbarian, against the powers of organized civilization. When I dream of Greece, it is always the Greece of early barbaric days when the first Aryan hordes came down, never the Greece of the myrtle crown and the Golden Age. When I dream of Rome I am always pitted against her, hating her with a ferocity that in my younger days persisted in my waking hours, so that I still remember, with some wonder, the savage pleasure with which I read, at the age of nine, the destruction of Rome by the Germanic barbarians.

But Lovecraft disagreed thoroughly, about both Rome and ancestral memory:

I have never found it possible to feel like anything but a Roman in connexion with ancient history. The moment history gets behind the Saxon conquest of Britain, my instinctive loyalty and intangible sense of personal placement snap south from the Thames to the Tiber with startling abruptness—so that I cannot help thinking of “our “ legions, “our” conquests, “our” flashing eagles, and “our” melancholy coming fate as foreign blood dilutes the old hawk-nosed stock and weakens our fibre in the face of barbarian invasion. I have a profound subconscious Roman patriotism which takes hold where Anglo Saxon patriotism leaves off; so that my nerve tingle curiously at such images or phrases as S.P.Q.R., Alala!, the Capitoline Wolf, Nostra Respublica, mare majorum, consuetudo Populi Romani, the toga, the galea, the short sword, the aquilae, or any really Roman place or personal name… I find myself disliking the later Empire and longing for the simpler days of the ancient Republic of Cato and the Scipiones. Toward the western barbarians (my own real blood ancestors) I find myself holding sentiments of mixed fear and respect. I recognize their Roman-like strength and aggressiveness, and fear they will retain them longer than “we” (the Roman people) can manage to do.

I’m personally with Lovecraft, but Howard inexplicably refused to be a Romeaboo:

My antipathy for Rome is one of those things I cant explain myself. Certainly it isnt based on any early reading, because some of that consisted of MacCauley's “Lays of Ancient Rome”7 from which flag-waving lines I should have drawn some Roman patriotism, it seems. At an early age I memorized most of those verses, but in reciting, changed them to suit myself and substituted Celtic names for the Roman ones, and changed the settings from Italy to the British Isles! Always, when I've dreamed of Rome, or subconsciously thought of the empire, it has seemed to me like a symbol of slavery—an iron spider, spreading webs of steel all over the world to choke the rivers with dams, fell the forests, strangle the plains with white roads and drive the free people into cage-like houses and towns.

And there the conversation lay for six months or so, until Howard made passing mention of his unfamiliarity with the ancient world.8 Lovecraft wrote back a long and impressionistic description of the differences between the Greeks and the Romans,9 and Howard in turn sighed that they simply didn’t hold his interest:

I am unable to rouse much interest in any highly civilized race, country or epoch, including this one. When a race—almost any race—is emerging from barbarism, or not yet emerged, they hold my interest. I can seem to understand them, and to write intelligently of them. But as they progress toward civilization, my grip on them begins to weaken, until at last it vanishes entirely, and I find their ways and thoughts and ambitions perfectly alien and baffling. Thus the first Mongol conquerors of China and India inspire in me the most intense interest and appreciation; but a few generations later when they have adopted the civilization of their subjects, they stir not a hint of interest in my mind. My study of history has been a continual search for newer barbarians, from age to age.

At this point Lovecraft made a noble effort to turn it into a debate: being civilized, he argued, was simply better:

It seems to me that a vigorous, intellectual, and orderly civilisation at its zenith (not the uncertain, decaying world of today) is about the best system under which a man can live. I can’t see why the half-life of barbarism is preferable to the full, mentally active, and beauty-filled life typical of the age of Pericles in Greece or (to a lesser extent) the age of the Antonines in Rome or the 1890’s and 1900;s in pre-war England and France. The exaltation of the spirit of physical struggle to a primary and supreme value is obviously a purely artificial and temporary attitude, determined by the historic accidents of one stage only in the evolution of the social group. When this quality is regarded more intelligently—esteemed, that is, in its proper proportion beside other qualities (reason, taste, cultivation, talent, etc.) of equal importance—we cannot help feeling that the race has ascended in the scale of humanity—become better developed because more of the capacities and functions are recognised and put in use.

But Howard just shrugs. Sure, he says, maybe! Art and civilization and so forth are all very nice…

Yet when I look for the peak of my exultation, I find it on a sweltering, breathless midnight when I fought a black-headed tiger of an Oklahoma drifter in an abandoned ice-vault, in a stifling atmosphere laden with tobacco smoke and the reek of sweat and rot-gut whiskey—and blood; with a gang of cursing, blaspheming oil-field roughnecks for an audience. Even now the memory of that battle stirs the sluggish blood in my fat-laden tissues. There was nothing about it calculated to advance art, science or anything else. It was a bloody, merciless, brutal brawl. We fought for fully an hour—until neither of us could fight any longer, and we reeled against each other, gasping incoherent curses through battered lips. No, there was nothing stimulating to the mental life of man about it. There was not even an excuse for it. We were fighting, not because there was any quarrel between us, but simply to see who was the best man. Yet I repeat that I get more real pleasure out of remembering that battle than I could possibly get out of contemplating the greatest work of art ever accomplished, or seeing the greatest drama ever enacted, or hearing the greatest song ever sung

Lovecraft keeps trying to argue that civilization is objectively superior because it creates peace and order that allow for the development of higher human experiences and the expression of “a million phases of pleasurable intellectual and aesthetic experience.” But Howard doesn’t want to have a debate: “I didn’t say that barbarism was superior to civilization. For the world as a whole, civilization even in decaying form, is undoubtedly better for people as a whole. … There’s no question of the relative merits of barbarism and civilization here involved. It’s just my personal opinion and choice.”10

But of course there is a question, because even resolutely subjective aesthetic claims are grounded in (or perhaps are the groundwork for) fundamental beliefs about what a man is and ought to be. Lovecraft thinks the best of humanity is exemplified by intellect, rationality, and order; he is enchanted by the mannered and dignified world of Augustan literature. “Certainly,” he writes, “the 18th century has never died so far as I am concerned!” And so it makes perfect sense that the horror of his weird fiction comes from reason failing, order overthrown or subverted, or — most awfully of all — shown never to have existed in the first place. Howard, on the other hand, thrills to the struggle:

It is the individual mainly which draws me—the struggling, blundering, passionate insect vainly striving against the river of Life and seeking to divert the channel of events to suit himself—breaking his fangs on the iron collar of Fate and sinking into final defeat with the froth of a curse on his lips.

He never makes any sort of overtly James C. Scott argument for barbarism, but you get the sense the two of them would have agreed that there is something more human about a life before or outside of civilization. And accordingly that’s the core of Howard’s fiction: his heroes are liminal figures, barbarians or outlaws or fighting men. He focuses tightly on them and revisits them again and again. Who even remembers the names of the people in Lovecraft’s best story?

But the thing is, you don’t actually have to pick! If we’re talking about aesthetic attraction and imaginative identification, you’re allowed to contradict yourself. Two visions can be logically incompatible and yet both contain true and beautiful things. You can see an “us” in the Romans and in the barbarians, depending on which part of the vast tapestry of human history is in focus right now.11 You can exult in the Promethean triumph over Nature but also embrace a holistic vision of the world. You can get a kick out of the amoral “never takes sides against the family” of the Godfather movies and still get a hyper-WEIRD rush from the story of Robert Graves’s train ticket:

You can delight with Lovecraft in orderly colonial streets, in “houses on the steep hill, with fanlighted doorways and double flights of railed steps rising from the old brick sidewalks,” and also with Howard in the vast unfenced lands of the West, “raw and bold and blazing, flooded by the fierce merciless flame of the western sun.” That’s the glory of art — it can pick out what is lovely in almost anything. But that’s its danger, too, and why it matters so much why you teach your children where to look.

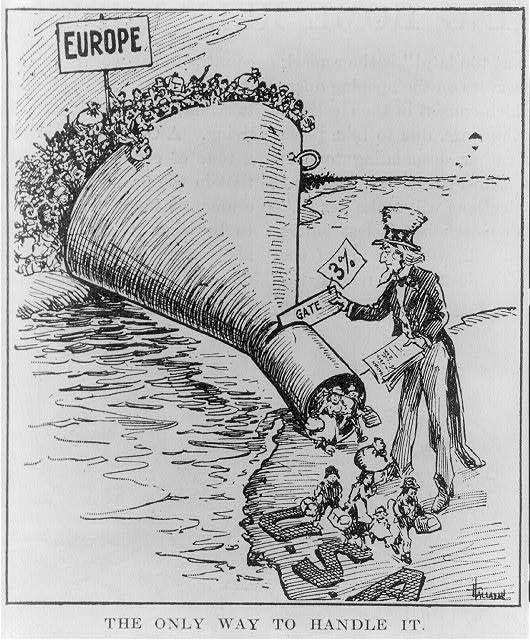

Lovecraft and Howard might disagree on barbarians, but they agree completely on one thing: immigration. They’re against it.

The great sluicegate of European immigration had already closed by the time they began their correspondence in 1930, but it was too late as far as they were concerned. They both lament what Howard calls the “overflowing of the country with low-class foreigners.” They mourn the changing character of American cities and, increasingly, countryside. Lovecraft worries that a mass of unassimilated foreigners have “create[d] the nucleus for a body of thought and aspiration antagonistic to the established order,” while Howard returns again and again to the growing “foreignization” of Texas. It all sounds awfully familiar! In fact, most of it could just as easily be put on the lips of any one of today’s immigration restrictionists; there’s even a version of the recent kerfuffle over whether Americans are entitled to something better than jobs managing a fast food joint.12 (The roughly contemporary arguments in favor of immigration also look pretty familiar.) But see if you can spot the difference here, in Howard’s description of what separates him from a Slovene communist who was trying to organize the Mexicans in San Antonio:

What, to him and his, were the traditions that lie behind me, and of which I am a part? How could the representatives of two such utterly separate stocks and traditions bridge the gulf between? It can not be bridged. Not in my life-time or his. What is Bunker Hill, Lexington and Paul Revere to him? What is King’s Mountain, the Battle of New Orleans, the drift of ‘49, Gettysburg, Bull’s Run, or San Juan? Nothing. A meaningless drift of words, talismans of a slow-thoughted breed, to him inferior, in his own mind. If the difference lay just in this country, it might be overcome. But it lies beyond that. What to him and his is Hastings, the Crusades, the Wars of the Roses, the Battle of Culloden, of Bannockburn, of Preston Pans, of the Blackwater. The Black Prince means nothing to him, nor Robert Bruce nor Shane O’Neil. The gulf will be bridged when our race—your’s and mine—is destroyed by the rising tide of such as he, and a mongrel breed, lacking all sentiment and tradition, reigns over the land our ancestors bled and sweat for. And I suppose it will come to pass. I dread their adaptability, their versatility. I could have broken this fellow half in two with ease, but it was easy to see which of us had the quicker, more alert mind. In an intelligence test he would have led me in a walk and not half tried.

Do you see it? The first half is completely recognizable, and a contemporary American could add plenty of examples from the second half of the twentieth century. But who today would list great battles of English history in their attempt to limn our national character? That’s not how we think of ourselves; if we listed them at all, it would be alongside things like Tours or Thermopylae or Lepanto, as part of our heritage from “the West” writ large. But to Howard and Lovecraft, American identity was ineradicably Anglo.13 When you read these letters, it’s almost charming when they’re racist about Swedes and Czechs — like, really? They’re northern and central Europeans! The Swedes are even Protestants! But it’s only strange because we’ve forgotten or abandoned the way they saw America. That version lost. And then the country spent the next hundred years creating a civic mythology around the one they hated and feared.

This is less a question of the actual facts on the ground, with statistics about national origin and GDP per capita and so forth, than it is an issue of imaginative identification. You might call the America that Lovecraft and Howard described America-1: a mostly-Anglo and heavily agrarian republic of doughty yeomen farmers, cultivated gentlemen, and intrepid backwoodsmen. It was the place Tocqueville visited, and it began to fade around the time of the Civil War.14 Its replacement in our collective consciousness — let’s say America-2 — is America as industrial powerhouse, America as melting pot: its touchstones aren’t log cabins or steeples on the village green but skyscrapers. This is the America that put a man on the moon, the America that poured the manufacturing might of a continent into a two-front global war and came out on top of the world for at least a generation. It’s the America of Ellis Island and the Hoover Dam. It’s the America the Chinese were imagining when they made their movie about the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. And by 1930, it was already there (just, as the saying goes, not evenly distributed). Lovecraft saw it:

I can feel no interest in the heterogeneous, traditionless industrial and mechanical empire which this nation threatens to become. Such a thing would not have enough coherence, continuity, memory-appeal, or identification with the historic stream to give me any satisfying sense of placement, interest, meaning, or direction. It might make a great nation—another Babylon or Carthage or Rome—but it wouldn't be my nation. What I belong to is the old English Colony of Rhode Island; and when that shall cease to have a cultural and psychological prolongation, I shall be a man without a country. I am too much of an antiquarian ever to feel a citizenship in a swollen, utilitarian national enterprise whose links with the past are cut, and whose instincts and sources have to do with scattered and alien people and lands and things—people and lands and things which have no connexion with me, and can have no interest or meaning for me.

And Howard agreed:

Once it was the highest honor to say: “I am an American.” It still is, because of the great history that lies behind the phrase; but now any Jew, Polack, or Wop, spawned in some teeming ghetto and ignorant of or cynical toward American ideals, can strut and swagger and blattantly assert his Americanship and is accepted on the same status as a man whose people have been in the New World for three hundred years.

But America-2 remembered America-1. That “melting pot” that Lovecraft blamed on the intelligent second-generation foreigners was in fact a deliberate project of the Yankee elite, an acculturation of the new immigrants into a specific American mythology that drew heavily on certain aspects of the old Anglo America (and ignored others). And it worked! Right now I’m reading through Laura Ingalls Wilder with a fresh set of kids, and at the opening of Little House on the Prairie (“A long time ago, when all the grandfathers and grandmothers of today were little boys and girls or very small babies, or perhaps not even born…”) I realized that actually, at that point, all of my ancestors were still in the Old Country. But my imaginative identification, my “oh, that’s us” is all with the pioneers, not with peasants eking out a living in the hills of Freedonia. I don’t think I’m alone in this: there are vast swathes of Americans for whom America-1 is what Rome was to Lovecraft. Maybe it would have reassured him if he knew.

Today there’s another vision, which I suppose I now have to call America-3: not agrarian America or industrial America, but America as a node in the global nexus of capital and labor. This is America as a home of skill and innovation, where dreamers and trailblazers from every corner of the world come together — the America of biotech labs and gleaming Silicon Valley campuses, LAX and JFK. America-3 is rich and clean: it makes things with hands at keyboards, or carefully ensconced in rubber gloves, or better still with robots. (Calloused hands, steel-toed boots, and mud belong to the visual glossary of America-2.) America-3 already rules in our largest cities, and probably London, Tel Aviv, and Amsterdam too. Like everyone else, I spend at least part of my time there: my image of America-3 is the Fourth of July barbecue where I ate smoked brisket on a Chinese steamed bun with spicy Indian chutney and drank an over-hopped German microbrew. (I brought a cake decorated with an American flag made of berries, but as the afternoon wore on the berry juices soaked through the powdered sugar I’d used to make stars and stripes and left behind only undifferentiated masses of blue and red.) And of course it’s also the America of Haitian asylum-seekers and Afghan refugees and millions of people crossing the southern border each year, because its animating ideology is free movement across borders for people, capital, and ideas.

It’s difficult for the opponents of America-3 to phrase their objections to it, though, because America-2 is itself a vision built on mass immigration. For Howard and Lovecraft “mongrel” may have been derogatory, but people today embrace it proudly: a “classic American mongrel” (Slovak, Sicilian, Scots-Irish, and Swedish) is never going to embrace immigration restriction as a matter of preserving ethnic identity. You can’t really engage with European-style fears of a “Great Replacement” if it already happened a hundred years ago! So instead the arguments are about legality and the need to “play by the rules,” which doesn’t actually address the question of America-3 at all. What should the rules be? You can see this in the recent fight about H1B visas: even if we set aside claims that the system is being abused, there’s still a fundamental tension in the Trump coalition between America-2 and America-3. Is our country about Bunker Hill and Gettysburg and Iwo Jima, or is it about a set of laws and institutions that make it easy for the best and the brightest to come here and do great things? Is America the home of a particular people, or is it the first truly global civilization? What kind of America are you trying to make great again, anyway?

There’s plenty more in these letters. Howard goes from fanboying Lovecraft to considering him a true friend and confidant;15 Lovecraft admires Howard’s poetry and gives him a crash-course on poetic meter;16 Howard shares tale upon tale of the West until Lovecraft urges him to write them down:

I agree that it is time someone arose to preserve in vital literature the deeds and traditions of the old southwest as it really was—and believe no one could fulfil that function better than yourself. You have assimilated a tremendous amount of historic data, and have a rare type of vigorous felicity in presenting it. What is more important still, you are phenomenally sensitive and responsive to the whole psychological background and sweep of pageantry. You feel the epic drama keenly and understandingly, and can throw a vivid, intelligent sympathy into your presentations. A pile of your letters is a choice slice of literature—and one can imagine what you could do if you really sat down to mirror inclusively and systematically the heroic march of events across the soil of your native region. I certainly hope you will attempt such a magnum opus some day, and believe it would have great chances of success.

Alas, the closest Howard ever came was the Conan story “Beyond the Black River,” where an obvious self-insert character dies bravely trying to match the deeds of a true barbarian. Still, it’s enchanting to imagine what he might have produced if he had lived, and I’m looking forward to the second volume of the letters to see what else he did write.

We don’t lock any of our posts, but those of you who are paid subscribers anyway should feel proud that you have enabled this sort of profligacy.

I don’t maintain that this is the best Lovecraft story, but it is my absolute favorite, probably because I read it while 1) doing a bunch of genealogical research and 2) uncovering some serious issues with an old house we did not end up buying. IYKYK.

The Insular Celtic languages comprise the Brythonic languages (Howard’s “Cymric”) like Welsh, Breton, and Cornish, and the Goidelic languages (Howard’s “Gaelic”) like Irish, Scots Gaelic, and Manx. Most Celtic languages, including many of the now-extinct Continental Celtic languages once spoken by the Celtiberians and Galatians (yes, the Galatians of Anatolia, St. Paul’s pen-pals, were Celts), are termed Q languages because they retain the proto-Celtic *kʷ. However, a few — including the Brythonic languages and the language of the Gauls — turn it into a P and so are called P-Celtic. (Think of the Welsh “mab” vs. the Irish “mac.”) Presumably the ancestors of the Gauls and Britons diverged from the rest of the Celts while still living in continental Europe, underwent enough linguistic drift to undergo that and a few other changes, and then settled in the British Isles; the question here was whether they arrived before the Gaels, who spoke a Q language. (The answer is that they did.)

In some sense I “grew up” in a certain place — I mean, I was physically there — but really I’m from a particular corner of the Internet in a particular era, and that’s only gotten worse.

I don’t have Lovecraft’s Selected Letters and I don’t plan to buy them. I mean it this time.

Hume is much more sensible:

‘tis utterly impossible for men to remain any considerable time in that savage condition, which precedes society; but that his very first state and situation may justly be esteem'd social. This, however, hinders not, but that philosophers may, if they please, extend their reasoning to the suppos’d state of nature; provided they allow it to be a mere philosophical fiction, which never had, and never could have any reality.

Howard:

I was, as always, much interested in your remarks concerning the classical world, of which I know so little. What a city Alexandria must have been! I had no idea of the origin of the word parchment. As I’ve said before, your letters are an actual education for me. Some day I must try to study the ancient Grecian world. Its always seemed so vague and unreal to me, in contrast to the roaring, brawling, drunken, bawdy chaos of the Middle Ages in which my instincts have always been fixed. When I go beyond the Middle Ages, my instincts veer to Assyria and Babylon, where again I seem to visualize a bloody, drunken, brawling, lecherous medley. My vague instincts towards classical Greece go no further than a dim impression of calm, serene white marble statues in a slumbering grove. Though I know the people of the classic times must have wenched and brawled and guzzled like any other people, but I can not conceive of them. The first mythology I ever read was that of Greece, but even then it seemed apart and impersonal, without the instinctive appeal I later found in Germanic mythology. Once I tried to write polished verse and prose with the classic touch, and my efforts were merely ridiculous, like Falstaff trying to don the mantle of Pindar.

Lovecraft:

We are precisely opposite in our reactions to the classic Graeco-Roman world, for it seems to me the only real and understandable period in history except the present. The Middle Ages, and the early Oriental cultures, seem very vague and unreal to me. The Greeks and Romans were, in the main, wholly modern in spirit. All that we are, except for certain impulses of Teutono-Celtic pride and mysticism, we draw from Greece and Rome. The Greek was an alert, intelligent, appreciative type of man; fond of argument and intensely proud of his tradition. He had the failings common to all men, though restrained from many extravagances by his innate taste and sense of proportion. His great virtue was his profound rationality; his great vice a tendency toward trickiness. He was a natural philosopher and scientist, and probably represents the highest biological organism developed on this planet. Under Roman rule he sank to humiliating depths of sycophancy and satellitism, becoming only a caricature of his former independent self. The name “Graeculus”, or “Little Greek”, became a term of contempt among the Romans from about the time of the Augustan age. Probably you wouldn’t care for the Greeks extensively, since they were above all things urban and sophisticatedly civilised. They did not (after the Achaean or Homeric element had become absorbed in the Dorian (native Minoan) population care for fighting on its own account, although they were conspicuously brave in battle whenever their civilisation and liberty were menaced—that is, until their decadent days after Roman conquest. They lacked political good sense, and always remained divided and mutually hostile city-states except for the brief period when Alexander welded together an Hellenistic Empire. Read the tragic writers Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, the comic dramatist Aristophanes, the historian Thucydides, and a few other representative classics (good translations are always available) in order to get a comprehensible “inside” picture of the Greek mind. The Roman differed widely from the Greek. He was cruder, more practical, less intellectual, subtle, sensitive, and aesthetic. He had a strong moral sense absent from the Greek, and a love of power for its own sake—plus a positive genius for order and organisation. He was less urban than the Greek, and made more of the country-gentleman type of life. He had a strict honesty not common among the rank and file of Greeks, but was deficient in humour. In war he was utterly bold and dominant—without fear and bent on sweeping all before him—though acting more from an intelligent desire to conquer than from the blind, joyous battle-impulses of our own Northern ancestors. Common life among the Romans was even more orderly than among the Greeks. Vice, though less frequent, was cruder and coarser. The Roman was more demonstrative in speech and gesture than is commonly supposed; though never as much so as the Greek. Contact with Greece softened the manners of the Romans, and gave them many of the rational, artistic, and cultivated characteristics of the Greeks themselves. At the same time this contact communicated many bad features, so that the fashionable vicious element acquired coarser habits of depravity than the Greeks had ever had. The old race-stock began to be vitiated by immigration and military colonisation as early as the 1st century B.C., and (according to the physiognomical evidence of realistic portrait busts) was thoroughly mongrelised by the 2nd or 3d century A.D. After the conquests of the Teutons in the 5th century A.D. and afterward, the “Romans” acquired a decadence not unlike that of the Greeks under the Roman rule, though less marked by tricky sycophancy and civility. It must be remembered, however, that these decadent “Romans” were not of the blood of Scipio and Caesar. In effect, they were the modern “wops” we know with such doubtful admiration.

Here’s the full passage:

I didn’t say that barbarism was superior to civilization. For the world as a whole, civilization even in decaying form, is undoubtedly better for people as a whole. I have no idylic view of barbarism—as near as I can learn it's a grim, bloody, ferocious and loveless condition. I have no patience with the depiction of the barbarian of any race as a stately, god-like child of Nature, endowed with strange wisdom and speaking in measured and sonorous phrases. Bah! My conception of a barbarian is very different. He had neither stability nor undue dignity. He was ferocious, vengeful, brutal and frequently squalid. He was haunted by dim and shadowy fears; he committed horrible crimes for strange monstrous reasons. As a race he hardly ever exhibited the steadfast courage often shown by civilized men. He was childish and terrible in his wrath, bloody and treacherous. As an individual he lived under the shadow of the war-chief and the shaman, each of whom might bring him to a bloody end because of a whim, a dream, a leaf floating on the wind. His religion was generally one of dooms and shadows, his gods were awful and abominable. They bade him mutilate himself or slaughter his children, and he obeyed because of fears too primordial for any civilized man to comprehend. His life was often a bondage of tabus, sharp sword-edges, between which he walked shuddering. He had no mental freedom, as civilized man understands it, and very little personal freedom, being bound to his clan, his tribe, his chief. Dreams and shadows haunted and maddened him. Simplicity of the primitive? To my mind the barbarian's problems were as complex in their way as modern man's possibly more so. He moved through life motivated mainly by whims, his or another’s. In war he was unstable; the blowing of a leaf might send him plunging in an hysteria of blood-lust against terrific odds, or cause him to flee in blind panic when another stroke could have won the battle. But he was lithe and strong as a panther, and the full joy of strenuous physical exertion was his. The day and the night were his book, wherein he read of all things that run or walk or crawl or fly. Trees and grass and moss-covered rocks and birds and beasts and clouds were alive to him, and partook of his kinship. The wind blew his hair and he looked with naked eyes into the sun. Often he starved, but when he feasted, it was with a mighty gusto, and the juices of food and strong drink were stinging wine to his palate. Oh, I know I can’t make myself clear; I’ve never seen anyone who had any sympathy whatever with my point of view, nor do I want any. I’m not ashamed of it. I would not choose to plunge into such a life now; it would be the sheerest of hells to me, unfitted as such I am for such an existence. But I do say that if I had the choice of another existence, to be born into it and raised in it, knowing no other, I’d choose such an existence as I’ve just sought to depict. There’s no question of the relative merits of barbarism and civilization here involved. It’s just my personal opinion and choice.

If you do it right, you can do both at the same time: there’s a dramatic moment in Rosemary Sutcliffe’s The Eagle of the Ninth where a survivor of a massacred Roman legion, gone native now beyond the wall with a British wife and children, reverts for a moment to his past:

They looked back when they had gone a few paces, and saw him standing as they had left him, already dimmed with mist, and outlined against the drifting mist beyond. A half-naked, wild-haired tribesman, with a savage dog, against his knee; but the wide, well-drilled movement of his arm as he raised it in greeting and farewell was all Rome. It was the parade-ground and the clipped voice of trumpets, the iron discipline and the pride. In that instant Marcus seemed to see, not the barbarian hunter, but the young centurion, proud in his first command, before ever the shadow of the doomed legion fell on him. It was to that centurion that he saluted in reply.

The version in the movie is not nearly so good, but you can probably see why they changed it.

Howard:

A broad belt of coast country from Port Arthur to Matagorda is dominated by the usual swarm of Poles, Swedes, Slavs, Latins, Germans etc. West of Cross Plains, the fertile grain country is inhabited thickly by Swedes and Germans, and this is the case with most of the richest parts of the state. The American farmer cannot compete with the low living standards and close economy and wheel-horse work of the alien farmer. He is slowly but surely being pushed off the best land, into the cities or on to worthless farms. Just now his last stand is on the great plains of western Texas, and he is supreme there, because its a big country, and a hard country, and no place for weaklings, and un-developed as yet. And for enduring hardships and taking big chances, for guts and stamina and man-killing work in huge, dynamic bursts, there never as and never will be a race to compare with the American of old British stock. Its not the fierce hardships that ruin the race- they can overcome any obstacle, so long as its big enough and hard enough to grip and trample; but the long, monotonous, grinding toil with a far-distant goal to view, the scrimping, and petty economy, the saving the pennies and living on bacon-rinds, the use of every inch of land, every blade of grass, every hogs bristle, all that whips the Anglo-American, viewed as a whole, while such things are second nature to the peasant from Europe. America must learn the craft of concentrated farming before her sons can compete with the scum of Europe. But who in the Devil wants to succeed by the bacon-rind and hog-bristle route?

Lovecraft:

Altogether, we may say that for 250 years a sound, compact Nordic-English culture existed in America undisturbed and unthreatened, with only such accretions as it could ultimately use advantageously in preserving the pattern. As late as 1880 there was no dispute as to what constituted the American type, or any doubt about the permanence of that type. New immigrants were all assimilable—joked about for their dialect during one generation, but with children who entered the native pattern and became the jokers instead of the joked-about.

Then—through a false and sentimental policy of ignoring ethnic lines and minimising heritage—the complexion of immigrants began to change. Economic rapacity demanded cheap labour, and the popular industrial policy was to rake in any sort of human scum with a low living-standard and correspondingly low wage-demands. Nordics of so squalid a sort couldn't be found, so Latins and Slavs were imported. The powers who started this, of course, had no idea of ever treating these immigrants like white people. What they wanted was a kind of serf just a stage above the slave-labour of former time— but they miscalculated the social forces involved, and did not understand that white races, however humbly represented, have a restless expanding power which makes it impossible to herd and segregate them absolutely at will. It was inevitable that the importation of millions of dissimilar aliens should cause a repercussion on the national fabric and create the nucleus for a body of thought and aspiration antagonistic to the established order. And so indeed it turned out. The brighter and stronger foreign elements acquired resources, influence, and spokesmen, and gave birth to the dangerous false ideal of “the melting-pot.” Forgetting what a well-defined and compactly crystallised thing the old-American civilisation was, they set up the familiar cry that “everybody's equally a foreigner except the Indians.” As if the conquerors and builders of the nation were on a par with the latest lousy Lithuanian dumped on Ellis Island.

Maybe bits of it still exist here and there — Utah, perhaps? Rural New England?

Howard:

I narrate and discuss matters with you, by letter, that I would’nt mention to my most intimate Texan friends. I trust your discretion, and anyway, you have no connection with the state or the people of which I might speak, and so are impartial and unprejudiced. I don't have to tell you that a lot of the things of which I speak are in strict confidence.

Lovecraft:

Your verses are splendidly vivid—and so generally accurate and regular that I am astonished by your disclaimer of metrical knowledge. Your case would seem to be an argument that good versifiers are such by instinct rather than by acquisition—“poeta nascitur, non fit”—a conlcusion which I had almost reached from a precisely opposite angle—i.e., the difficulty of making many persons able to create smooth and vivid lines even with the most careful instruction. But I think, none the less, that you wuld find certain rules and principles of assistance in composition. Read Brander Matthews’ “Study of Versification” or Gummere’s “Handbook of Poetics”. There are several basic metres, and many modifications of them. Iambic verse is that in which there are short and long stresses—like this— …

Great follow up, the Conan piece is your finest so far. Noteworthy that Houellebecq, the best critic of modern France, copped so much of his sound from Lovecraft and is among his more insightful readers.

Thank you for this review... I might now have to pick up a 60$ book (or hope the library network finds a copy).

I have read and re-read Howard's canon 2-3 times in the past year alone. They make great "I need something to read for 30 minutes before I can pass out" fodder, with a great style and prose that is enjoyable even when you know the next line before you read it.* Howard taking his own life was a great loss; one can only imagine what his magnum opus could have been. I don't really feel that anyone since has captured his voice or aesthetic sense quite so well.

*By contrast, "Children of Time" is taking me a long time to get through. Lots of really great ideas, but no characters that make me think "Oh, I wonder what they will do next!"