REVIEW: Cuisine and Empire, by Rachel Laudan

Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History, Rachel Laudan (University of California Press, 2015).

Many years ago, we discovered an incredible restaurant. It was on the first floor of a nondescript office building in the central business district of a nearby city, and by day it was one of those sandwich shops where people in suits swing by to grab a tuna melt and a bottle of Tropicana. It had some incredibly bland and forgettable name — “City Deli” or “Downtown Café” or something like that. But if you looked carefully, you would notice that there was something different about Downtown City Deli Café. For one thing, the walls had a lot of pictures of horses: some were photos, but more were beautifully illustrated images of armed and armored men on horseback. And hanging over the largest table, which we inevitably snagged…yep, that’s Genghis Khan.

Downtown City Deli Café, it turned out, was run by a family of Mongolian immigrants. During the day they served wraps and sandwiches to hungry office-workers, and in the evenings, when the business district emptied out, they made the food of their people (or an Americanized version anyway, there was a lot less mutton than you would find on the actual steppe). It was usually empty and the cooking took forever, but we didn’t mind — our little kids climbed all over the hideous public art installations outside, we got to chat while we waited for our food, and when it arrived it was hot and delicious. (And so cheap! This was before they invented inflation.)1 We ate khuushuur and mantuu and buuz, and probably other kinds of dough+meat dishes in a variety of configurations, and usually brought some home for breakfast the next morning.

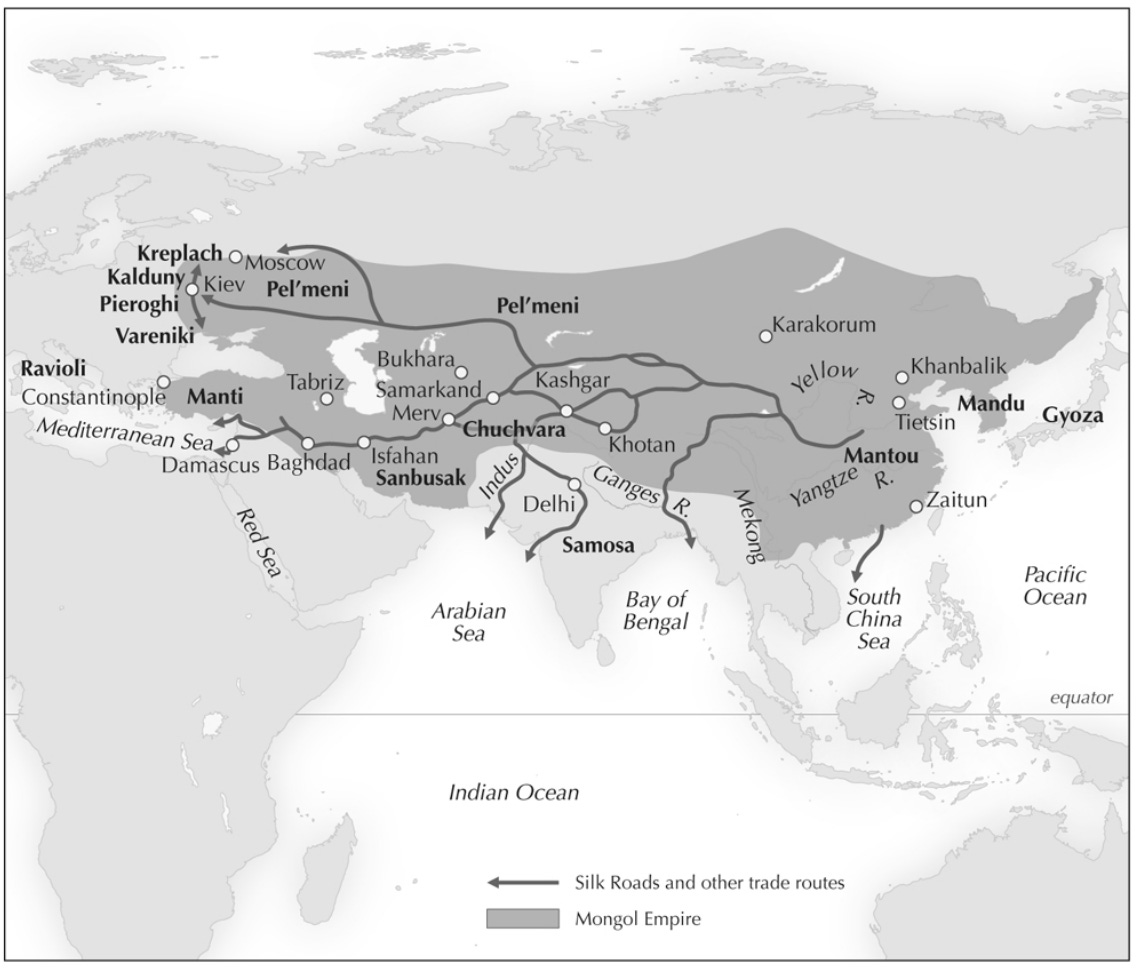

Alas, Downtown City Deli Café (or whatever it was called) didn’t survive its regular office crowd being sent home in the spring of 2020, and whatever lunch spot is now in its place has many fewer pictures of the Great Khan. But our beloved buuz, steamed dumplings of ground meat and onion inside a pleated wheat dough wrapped, are still with us: they’re the khinkali at a Georgian restaurant, the manti at the Turkish market, the great frozen sacks of pelmeni at the Russian grocery. And while they probably weren’t Mongolian to begin with, it was our dining companion Genghis Khan who was ultimately responsible for their spread across Eurasia.

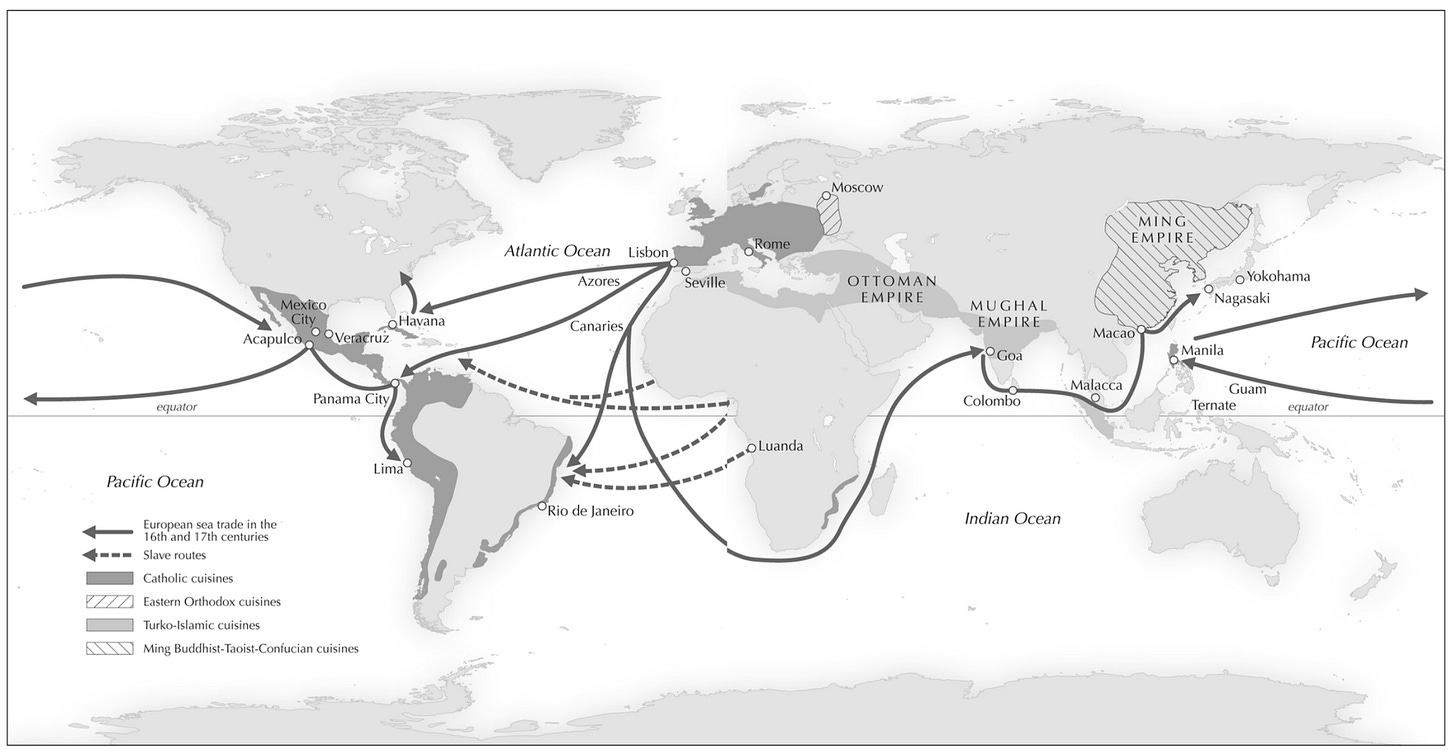

You’ve probably seen this map floating around on the Internet, and this is the book it comes from. There are lots of other cool maps, too — the transfer of curry under the British Raj, the “bread debates” of the twentieth century — but despite appearances Cuisine and Empire isn’t really a history of ingredients or even cooking methods, just as a history of architecture isn’t really about innovations in forestry or framing techniques. Rather, it’s a history of the entire cultural bundle we call a “cuisine,” which obviously includes raw materials and ways of turning them into food, but also has a lot to do with ideas. What is food? What is cooking? What role do they play in human society and the natural world? How about the supernatural world? And what’s the relationship between cooking and the state?

Those sound like strange questions — what do you mean, what is food. It’s the stuff you put in your mouth to make your body run, next question. But even that simple version is itself a belief about food, and even the most reductive Soylent-swiller probably has some thoughts about macros. (In fact, I bet “supplement stacks” are over-represented among Soylent people; caring a lot about nutrition don’t necessarily track with caring a lot about cooking.) And as soon as you get beyond “food is fuel,” it starts to become obvious how many different places you can go. What does your meal look like? Who makes it? How does that person choose what to make? With whom do you eat? Is your food in some sense connecting you to a primordial, pre-existing world, or is it a triumph over and improvement on that world?

Rachel Laudan isn’t the first person to attempt a global history of how people cook and eat, and her excellent introduction and footnotes are a wealth of resources for anyone who’s curious. (I am a little smug about how many of them I had already read.) But her comparative discussion of culinary philosophy — the set of ideas and principles that lead people to cook a certain way, and the way that new ideas lead people to new cuisines — is novel. We can, after all, pretty easily discuss what people ate in the past: you’ve almost certainly enjoyed a fancier version of the Sumerians’ wheat-based flatbreads, and perhaps even the Shang Dynasty’s steamed millet. It’s far more difficult to really wrap our heads around what food meant to them. (Worldviews are incredibly difficult to bridge.) But all over the world, the earliest recorded culinary philosophies look pretty similar.

Cooking was seen as a fundamental cosmic process, an integral part of a holistic, ordered, and hierarchical universe. Each kind of creature had its appropriate food: animals eat raw foods while standing, humans sit or recline while eating cooked foods, and the gods enjoy the fragrant aromas. But there were more hierarchies within these divisions: the right food for a slave or a peasant was very different than the food for a king, and eating the wrong kind of food might cause illness or even physical degeneration. (This particular kind of hierarchical thinking survived into the early modern period, when Tudor doctors confidently explained that the stomach of a laborer, burning hotly to fuel his brute physical tasks, would immediately burn up the refined foods appropriate for a gentleman, while a gentleman’s digestion would be too moderate to extract any benefit from the coarse meals of a ploughman.)

Beyond that, though, cooking was a symbol of civilization.2 Partly this was just because cooked food (and ideally cooked grains) were considered the right kind of food for human beings: non-agricultural peoples who didn’t eat grains might as well not cook at all, and in fact their literate and settled neighbors often claimed they didn’t. But there’s more to it than that: the pot itself stood for the state, and wise rule was likened to being a cook, all of which comes back to a picture of cooking and nature diametrically opposed to our own.

For modern Western society, natural means minimally processed, as close as possible to the way the food grew: brown rice is more natural than white, corn on the cob is more natural than tortilla chips, roast chicken is more natural than homemade breaded tenders which are in turn more natural than McDonald’s nuggets, and just about anything is more natural than that carbonated protein stuff. “Farm-to-table” is a trendy label for restaurants because it elides the kitchen entirely (although patrons and health inspectors alike would probably be alarmed if steaks showed up still mooing).

But for the ancients, the nature of a thing was what was revealed by cooking it. Just as the refiner’s fire transforms dull rock into sparkling metal, so too the backbreaking work of reaping, threshing, winnowing, milling, and baking transforms raw wheat into its true and proper form: bread. Wise governance was meant to do the same thing to people, transforming a raw brute into a civilized human being. A Confucian writer offers this metaphor for kingship:

You have the water and fire, vinegar, pickle, salt, and plums, with which to cook fish and meat. It is made to boil by the firewood, and then the cook mixes the ingredients, harmoniously equalizing the several flavors, so as to supply whatever is deficient and carry off whatever is in excess.

Cooking, like civilization, was the process of transmuting3 the “facts on the ground” into their highest form, revealing their true nature. Cooked was therefore better than raw, more cooked was better than less cooked. Not for the ancients our lightly dressed green salads!

There are two directions to take this. You might pretty easily conclude that the modern idealization of “natural” food is in some sense fooling ourselves: if you’re actually involved in the steps necessary to render something even theoretically edible, like harvesting and threshing grain or killing and skinning an animal, the final steps to make it delicious and easy to eat seem like an obvious continuation. (Even the raw food people chop their meat up small; human teeth just aren’t designed for tearing of hunks of raw flesh, however much my toddler tries.) Some people think serving your family farro with tomatoes is more “natural” than doing the same thing with pasta, but it only seems that way if you’re totally alienated from the giant pain in the butt that is removing the hulls from emmer wheat. Hey, it still looks like a seed, right?

But let’s take seriously for a moment the ancient world’s metaphorical connection between our food and our political order, the idea that cooking does to raw ingredients what society does to human beings, and suddenly the cult of crunch comes into focus. It’s just Rousseau. Or rather, it’s the equivalent of the insistence we see in Rousseau and his heirs, left and right, that modern institutions have deformed us and made us less human. If man has a telos, a role and vocation that isn’t satisfied by simply existing as a member of the human race, then society can be structured in ways that support and enable the realization of that telos — or in ways that make it impossible to achieve, pervert it, and ultimately crush it underfoot.4 And so too with food: our cultural obsession with things “natural” and “unprocessed” isn’t a literal desire to chow down on the grass of the field, it’s a fear that the true nature of foods that ought to be revealed and perfected in cooking are instead perverted by a wicked and uncaring system. It is, in short, a culinary philosophy, and as such it reflects broader trends in our understanding of humanity, the natural world, and the state.

I won’t rehash every one of Laudan’s stories, which move from the ancient world to the rise and spread of Buddhist cuisine (steamed rice, sugar, and ghee; no alcohol or meat) and the development of Islamic and Christian cuisines out of the combination of new religious ideas with existing practical and philosophical elements. (Islamic cuisine, for instance, drew heavily on Sassanid Persian foods, while the Christian ascetic tradition hearkened back to the republican Roman preference for simple, wholesome dishes rather than gluttony-inducing sauces and sweets.) There’s a great deal of borrowing throughout, but it mostly goes one way: from India to China, or from Muslim territory to Christian Europe after the Crusades.

Most dramatic is the Columbian Exchange — which from a culinary (rather than biological) perspective, Laudan argues, never actually happened. Old World cuisines were transported wholesale to the Americas, and maize, tomatoes, and potatoes were eventually established in the Old World, but they made the move shorn of the processing and cooking technologies that turn an ingredient into part of a cuisine. She also has an excellent treatment of the rise of “ethnic” cuisines and the development of “a new culinary philosophy according to which every nation had a long-standing traditional cuisine worth exploring for its delicious taste” and authenticity. (These “long-standing traditional cuisines” were usually invented in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century out of spare parts from the last five hundred years of culinary history, then promulgated as representing the true soul of the nation. They’re mostly pretty tasty, though!)

But instead of getting into all of that, I’m going to tell you about just one of the transitions Laudan documents, because it sheds particular light on the way we eat today (or, at least, yesterday): the transition of European high cuisine from medieval “Catholic cuisine” to French cuisine.

If you’ve ever poked around in a medieval cookbook (and if you haven’t you should try it now, this one is good), you may have found the food was rather unfamiliar. And while I do like my materialist explanations — the cooking environment has changed a lot! — most of it is just that the preferred flavor profiles are also wildly different. Here’s Laudan’s description of Catholic cuisine by the fourteenth century:

The grand dishes included roasts, pottages, meats cooked in acid sauces or sauces thickened with nuts and spices, a carefully balanced puree of rice and chicken sprinkled with sugar (blancmange), and pies and tarts of all sizes… The sauces of Catholic high cuisine were based on vinegar or verjuice (the acid juice of unripe grapes) flavored with spices, including sugar, to carefully balance the cool moistness of the vinegar with the hot, dry, pounded spices; the whole was thickened with breadcrumbs and nuts. One of the most popular sauces was cameline. “To make an excellent cameline sauce, take skinned almonds and pound and strain them; take raisins, cinnamon, cloves, and a little crumb of bread and pound everything together, and moisten with verjuice; and it is done.”

Tastes that we associate mainly with dessert — warm spices like cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg, plus a hefty dose of sugar — show up everywhere in medieval food, including in heavy meat dishes. Perhaps the closest things in modern circulation are agrodolce sauce, a sweet-sour balsamic-vinegar-and-fruit condiment that goes nicely on pork, or vinegary Filipino adobo. In fact, elements of Catholic cuisine survived best in regions of the former Spanish colonial empire, because the Spanish resisted the rise of French cuisine. The legacy lasted long enough that mole poblano — a dish derived from the spicy stews brought to Andalusia by the Muslim conquest, adopted by Catholic Spaniards, and imported to the New World by the colonial elite — was reinterpreted by Mexican nationalists in the early twentieth century as a symbol of the seamless mixing of peoples into a diverse nation.

So anyway, while I could easily afford to buy enough spices to beggar King Richard II, I don’t; we don’t cook like that any more. Instead, around 1650, Catholic cuisine was comprehensively replaced. And if you think about the timing for a moment, that makes sense: the Protestant Reformation had fractured European culture, and once the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope, the signaling value of sugar and spice began to drop along with their prices. There was an ideal opening for a rival cuisine to emerge as the high status choice. The eventual victor — which arose in France, reigned supreme for centuries, and continues to influence the way we eat today — was notable for “its multiple ways of combining fat, flour, sugar, and liquids to make new kinds of sauces and sweets, its use of meat essences for flavoring, and its employment of whipped egg whites and cream to create light, airy textures.” La Varenne, the first codifier of this way of cooking, instructed the cook to “take a little diced pork, place it in the saucepan, and when it has melted down, take it out, and mix in a little flour that you allow to brown well and dilute it with bouillon and vinegar.” That’s the first known recipe for a roux, and far closer to how most sauces are made today than the cameline!

If the rich sauces of the classic French cuisine are unfamiliar to you, that’s because they were displaced as the global haute cuisine in the second half of the twentieth century — first by the lighter, more delicate flavors of nouvelle cuisine5 and then by the ingredient-forward, chef-driven style that came out of California. (A great book on this shift, and much more, is Paul Freedman’s Ten Restaurants That Changed America.) But from 1650 to 1950, sauces like béchamel and sauce espagnole were the only game in town for fine dining — and they arose from a novel theory of human biology that lasted barely a century.

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Paracelsus and his followers promulgated a physiological theory that contrasted sharply with the Galenic medical establishment that had prevailed since the classical era. Inspired by experiments in distillation, they denied the existence of the four elements (earth, air, fire, and water) and instead argued that there were only three: salt, like the solid residue that gave food its body and taste; oil, like the oily fluid that made things unctuous; and vapor, the pure essence of whatever was distilled, that gave foods lightness and aroma. They also argued that fermentation, not cooking, was the fundamental process involved in digestion, so anything that rotted quickly must be especially easy to digest — particularly fresh fruits, herbs, and vegetables, overturning centuries of traditional avoidance of raw plants.

Given the weakness of Catholic cuisine, the new theory arose at just the right time was eagerly adopted by cooks and the general public. Vapor in particular was considered nourishment for the brain, so sparkling water became popular, as did cakes raised with beaten eggs, whipped creams, and mousses. Simmering meat and fish to extract their essence was also a valuable vaporous technique. And most importantly, cooks began to experiment with sauces based on these theories, in which butter or lard (oily) bound flour (salty) with wine or stock (vaporous).

French cuisine’s favored ingredients were “beef, chicken, butter, cream, sugar, fresh herbs, vegetables, particularly asparagus and peas, and fruits such as pears, peaches, and cherries. The flavors came not from spices but from meaty bouillons.” Laudan goes on to give some examples:

Often they were based on a coulis, an extraordinarily rich, expensive, and time-consuming broth thickened with pureed meat. For four quarts, a couple of slices of ham might be browned with two pounds of veal, carrots, onions, parsley, and celery, then covered with stock, bouillon, or broth, simmered until done, and then thickened with a roux made with half a pound of butter and three or four large spoonfuls of flour.

As famously popularized by Carême and simplified by Escoffier, French cuisine became first the pan-European and then the global standard for fine dining. Cooks around the world Frenchified their local foods by adding vinaigrettes, mayonnaises, béchamels, and pastry, creating now-familiar dishes like pastitsio, lasagna, and beef stroganoff. And yet by the time Russia, Hawaii, and Mexico tried to adopt haute cuisine, the physiological theory that had underlain it all had long since shriveled up and died, replaced in the eighteenth century first by the idea that health depended on the balance of acid levels and then by a new understanding of the chemistry of nutrition. But it didn’t matter: culinary philosophies may grow out of other ideas about the world, but then they take on a life of their own.

There are a dozen other equally fascinating stories in this book — I haven’t even touched on the USA’s nineteenth century transition from a cuisine of pork, molasses, and cornmeal to one of beef, sugar, and wheat flour — but they all boil down to the complicated interplay of material conditions and human ideas about the world. Yeah, sure, new ingredients — or new methods of transporting, storing, and processing old ones — do a lot to change how people cook and eat…but new ways of thinking and talking about food do as much or more. And we can’t really understand why we are the way we are unless we know how we got there.

How much of our fondness for “ethnic food” comes from the same semi-mystical fetishization of non-white people that gives us an entire New York Times article about an Arabic word for, uh, being a good cook?6 How much does the rise and fall of convenience foods (as an aspiration, anyway — we still use them plenty in practice) track not only tired housewives’ gratitude for labor-saving shortcuts but the broader cultural preference for scientific solutions? (Baby formula and frozen TV dinners took off commercially around the same time.) And it isn’t a coincidence that the reflexive skepticism of Big Agribusiness that gives us beef tallow french fries and raw milk has become right-wing just as the institutional heft of Big Everything shifted left. The world we know is built out of human choices made for complicated human reasons, and ideas have consequences in the grocery aisle too.

It was also much less spicy than comparably-priced “ethnic” food, which was a win in an era when ketchup was “too hot” for one of the Psmithlings.

Consider here the Chinese distinction between “raw” and “cooked” barbarians.

The alchemical metaphor would become incredibly popular, especially in discussing white sugar, where the spiky green grass → sparkly white powder transition is so visually dramatic.

If this seems too nice to Rousseau, do go read that book review from my husband I linked above.

Also French, of course. Please imagine a beret on this guy: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

“This word is untranslatable!” they announce, before glossing it in about three.

"And while they probably weren’t Mongolian to begin with, it was our dining companion Genghis Khan who was ultimately responsible for their spread across Eurasia." True, and you can tell that because they contain wheat flour. Moreover, if you find a Mongolian dish with flour, the name is 95% likely to be Chinese. Khuushuur is huashao'r: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%81%AB%E7%87%92%E5%85%92_(%E8%92%99%E5%8F%A4%E9%A3%9F%E5%93%81), mantuu is mantou: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantou, and buuz is baozi by name but in fact refer to steamed "pot stickers," zhengjiao: https://www.tasteatlas.com/zhengjiao . In fact, the terminology for these dishes is systematic and interestingly different from the Chinese. As I explained in a lecture on culture I gave to a bunch of American undergrads who came to Mongolia for a zoological expedition, what Chinese call small jiaozi or zhengjiao are bansh (from a different Chinese term, bianshi, so it sort of lines up with Chinese usage; however, in Mongolia you usually boil them in milk tea for breakfast, which is very very non-Chinese); if the meat is inside an unleavened shell, it's called buuz; a steamed leavened bun is called mantuu (this one lines up with Chinese usage); and if it is meat inside a steamed leavened bun, Chinese baozi, it's called mantuun buuz: https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?q=mantuun+buuz&mid=5E099BDDF50587D003925E099BDDF50587D00392&mmscn=stvo&FORM=VIRE . (This was of course one of their two favorite parts of the lecture.)

As an amusing dessert to that linguistic feast, Mongols even have moon cakes, yuebing, only they make them from flour instead of red bean paste, and fill them with things like cinnamon and sugar. They're called yeeveng and I suspect started in Inner Mongolia. These are examples of the ceremonial ones you stack up at the big feasts: https://www.olz.mn/product/21833

Synthesis: ethnic food is legitimately the best, but mostly because it's a crazy mishmash of influences, not because it's somehow "pure" or "foreign".

You can't do better for comfort food than a Mission burrito (invented by Mexican corner groceries in Sixties SF) with al pastor pork (adobo-style pineapple sauce, Lebanese cooking method), sour cream (Eastern European by way of the Northeastern US), and shredded cheese and lettuce (extremely American fixings).

Great review!