BRIEFLY NOTED: Further Arguments Against Jared Diamond

I was one-shotted in my teens by the way Guns, Germs, and Steel ✨explained everything✨ and I’ve been chasing that dragon ever since. At this point honestly half the books I’ve reviewed could probably be described as arguments against Jared Diamond. But that’s okay. I can stop any time. Just one more sweeping transdisciplinary exploration of global history. Just let me see a map of British coalfields next to a chart of GDP per capita and I promise I’ll go back to that book about esoteric writing. C’mon, bro, I won’t ever talk about the Hajnal Line again, I swear. Just let me have one more study of an under-appreciated causal factor for the differing trajectories of human societies and I’m done. I have this under control.

Plagues Upon the Earth: Disease and the Course of Human History, Kyle Harper (Princeton University Press, 2021).

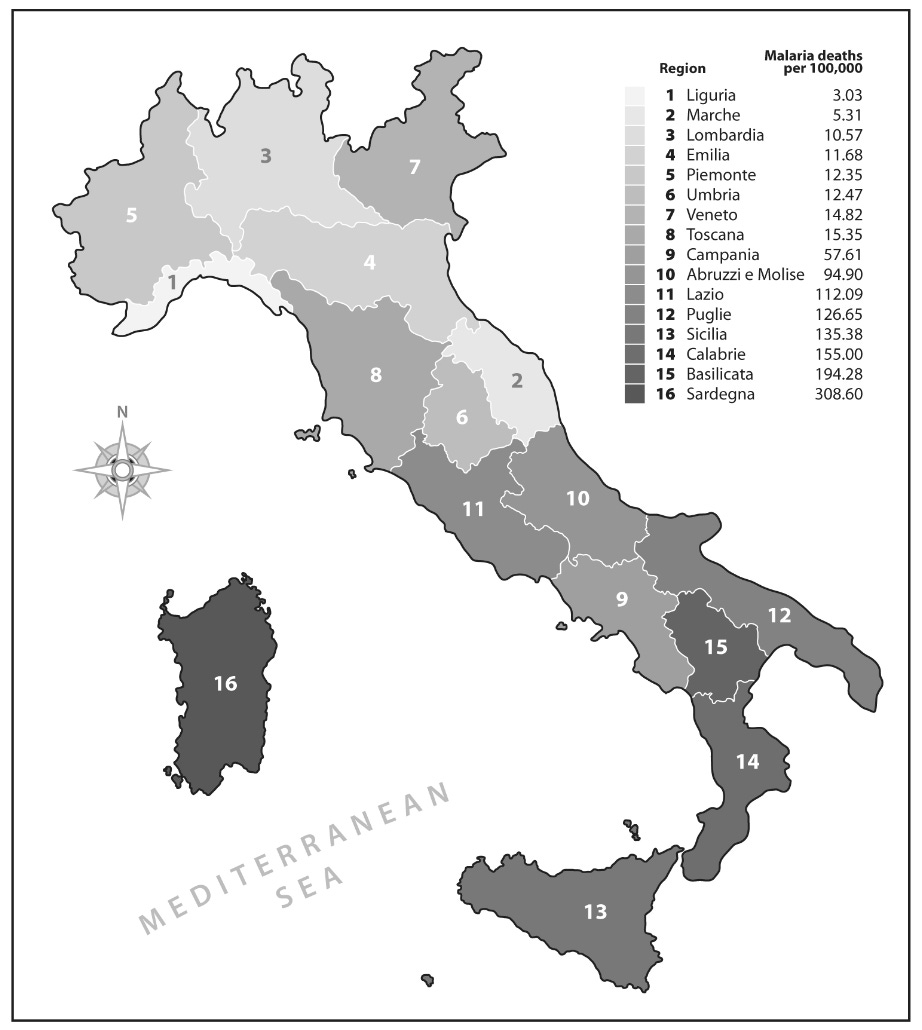

Fun fact: the division between wealthy, industrialized northern Italy and low human capital, fast life history, amoral familist southern Italy lines up almost perfectly with the natural range of Plasmodium falciparum, the protozoan that causes the most virulent and deadly form of malaria.

In retrospect, reading this book while visiting a particularly wet part of the country during a particularly wet summer may not have been the best call I’ve ever made. Yes, I am rationally aware that, thanks to the sterling efforts of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Boy Scouts of America, and the Malaria Control in War Areas program among others, American mosquitoes have been a nuisance rather than a danger for seventy-five years. Yes, I know that even if I positively identify the mosquito that’s currently sucking my blood as Aedes aegypti, the “yellow fever mosquito,” I’m not actually going to get yellow fever. And yet I spent a solid week having a knee-jerk oh no we’re all going to die every time I heard the telltale whine in my ear.

But weirdly, it was only the mosquitoes. There I was, immersed in a history of infectious disease and therefore poised to overreact to any reminder of the myriad ailments that have plagued humanity for the last several million years, and only the insect vector of a few mostly-eradicated diseases was even around to prompt a case of second year syndrome. I didn’t run into dirty water, or suspicious meat, or visible sores, or coughing or sneezing or fever — not even a rat or a louse or a fly.1 That’s pretty incredible! Here are all these things that used to leave our ancestors weak or sick or dead, and we’ve learned to control them so well that a few years ago societies worldwide shut down over a virus whose fatality rate is a rounding error compared to the fevers and fluxes of the past. In fact we’re so good at controlling infectious disease that it’s often not even on our radar, and that makes it very hard to really wrap our heads around what life was like in the past — which is surely one of the goals of studying history. So thank goodness for Kyle Harper.

Harper is an eminent ancient historian and the author of several books on the late Roman Empire. In the most recent of them,2 the excellent The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, he argues that exogenous shocks like the end of the Roman Climate Optimum and three dramatic plagues (Antonine, Cyprianic, and Justinianic) played major roles in destabilizing the Western Empire — if they hadn’t, we might well talk about the “Crisis of the Fifth Century” instead of the Fall of Rome. Here, probably inspired by his research on the role of infectious disease, he widens his scope to take in the vast sweep of humanity’s interactions with the many, many, many organisms that can make us sick. How many? Well, it depends who you ask and how you count:

One standard and often cited catalog of human pathogens includes 1,415 species. A more recent and systematic survey identified 1,611. Oddly enough, there is only about 60 percent overlap between these lists, so the number of unique pathogens identified between them is 2,107. Yet the Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Online Network (GIDEON), a standard database of infectious diseases created for clinicians, lists 1,988 bacteria alone that have been found to infect humans. More than one thousand of these are not in either of the other lists…

This isn’t (mostly) the triumphal tale of mankind’s glorious victory over disease, though the final chapters do have something of that flavor; rather, it’s a thoughtful and richly detailed analysis of all the ways infectious disease has shaped human history. And yes, the second half gives you all the familiar beats, the charismatic megafauna (microfauna?) of epidemiology (bubonic plague, smallpox, HIV) though the stories are told well and updated with aDNA evidence since the last time I read a big “here’s all the stuff that used to kill people” book,3 but to my mind the really good stuff comes in the first half.

When we think about disease, we tend to think about the plagues of civilization, the kind of big, headline-making diseases that do things like burn through an unexposed population in the space of weeks or months, or empty out cities as people flee to the countryside (and bring their germs with them). Even the slower-acting of the “famous” diseases get short shrift, despite the fact that over the course of human history tuberculosis has killed more people than smallpox. On one level this makes sense: these are big dramatic events, a whole ton of people dying all at once has a visible and enormous impact on your society, and if we’re looking to disease for an explanation of How The World Got This Way then epidemics are obvious inflection points. (Also, these diseases played an outsized role in the success of European colonialism in the New World, with which guilty white liberals are fascinated — but you could tell an equally compelling story about the role of tropical diseases in stymying colonial expansion into Africa, as indeed Harper does.)

But they are, as I said, the plagues of civilization — all those exciting, dramatic diseases can only sustain themselves among dense human populations enabled by the spread of agriculture and the state. If we focus on them too much, in other words, we’ll ignore the disease burden of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, which the standard narrative wildly understates.

We know that many contemporary hunter-gatherers are riddled with parasites and bacterial infections, and that while their disease burden seems to be lower than that of agricultural societies, it’s still way higher than for our closest relatives. (One metastudy estimated that infectious disease accounts for 54% of chimpanzee deaths but 72% of hunter-gatherer deaths.) And many of these pathogens go way back. The clade of schistosomiasis that infects humans, for example, branched off in Africa several hundred thousand years ago and may actually predate our species. Whipworms and hookworms migrated with us in the Pleistocene. Vector-borne diseases — especially those transmitted by mosquitoes — can sustain a chain of transmission even among widely-dispersed populations, especially when they can establish chronic infection: P. vivax, the relatively less deadly form of malaria, dates back at least 70,000 years and possible as much as 250,000, and the nematode that causes lymphatic filariasis emerged in Southeast Asia about 50,000 years ago. Forget the popular image of “primal communities” living in harmony with nature only to be interrupted by agriculture’s zoonotic “crowd diseases”: our hunter-gatherer ancestors were plagued with hideous afflictions we modern Westerners can hardly imagine.

Oh, and it also turns out that rather than bovine tuberculosis spreading to humans after we domesticated cows, we actually gave it to them. Twice.4 Also to chimps and dolphins. In fact, the human-adapted strain seems to be ancestral to all the animal strains of TB.5 Whoops.

After the rise of agriculture nothing in this book really upends the broad strokes of the traditional story, but Harper does interestingly complicate everything and suggests plenty of ecological factors that might shed light on the differing courses of human societies. Read it this winter, before the mosquitoes come back.

Argument Against Jared Diamond Factor: 3/10

The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution, Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending (Basic Books, 2009).

Yes, this book is old enough to drive, in a field where the science changes so fast that something only a few years old can be hopelessly dated. Yes, it is full of things like “we think Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans probably interbred but we don’t know for sure…” (Now we do know, and they were right.) And yes, many of its other suggestions are far from proven one way or the other. But as a theoretical argument for what we might plausibly expect to find as we investigate the human genome, and as one useful interpretive lens for human history, it sure holds up.

The core of Cochran and Harpending’s argument is simple: the Neolithic Revolution profoundly changed our environment, which introduced novel selective pressures. Under these new conditions, even small mutations could provide the bearer enough of an advantage that they spread quickly through a population — and even small mutations can have enough of an impact on behavior to explain some (or even much) of the observed diversity of human cultures and societal outcomes.

The first part of this is uncontroversially true. We know that there was rapid and strong selection for pale skin in northern Europe after 6000 BC, probably because the new agricultural diet was so much lower in vitamin D that it became very important to absorb it from sunlight. We also know that several unrelated lactase persistence mutations began to pop up among different populations when they began to domesticate dairy animals, and that genetic variants that protect against diabetes and alcoholism spread after the adoption of high-carb, easily-fermentable Neolithic foods. A recent preprint6 analyzing the genomes of 15,000 West Eurasians over the last 14,000 years suggests equally strong selection in hundreds of different places, including genes related to the immune system and blood types — but also in polygenic traits like height and IQ/income/educational attainment (all of which are pretty closely correlated in modern societies for obvious reasons).

The real question, then, is the second half of their argument: is it plausible that the kinds of small mutations that have had time to accumulate in the last ten thousand years could have changed their bearers’ behavior enough to have meaningful influence on the ways societies developed? After all, the genetic variants that have swept through populations since the Neolithic Revolution all involve tiny changes to the genome, sometimes just swapping one base pair for another. Are any of those enough to explain the stunning cargo disparity? And the answer is…well, maybe.

Cochran and Harpending suggest a few sweeping neurological genes that may have played a role, most notably ones that affect neurotransmitters and brain development, but the problem is that we don’t actually know what those genes do. Instead, they focus on describing the sorts of novel selective pressures that people suddenly began to face when they entered (or were forced into) state societies: following the rules and submitting to authority isn’t a particularly valuable trait if you’re a hunter-gatherer, because there’s no one who’s going to cut off your head, but it’s really important if you’re routinely subject to corvée labor and would like to live long enough to have kids. Similarly, being good at delayed gratification is a much more useful trait for people whose daily lives involve seed corn and breeding stock that should remain uneaten than it is for people who can just go find another stand of grain or herd of animals. And it certainly seems, from our experience of animal husbandry and Belyayev’s famous experiment in silver fox domestication, that human-driven artificial selection can produce dramatic behavior differences in remarkably few generations; natural selection is slower, but the principle stands.

So yes, it’s very plausible that agricultural state societies created novel selective pressures that produced cognitive and behavioral changes in their populations. In fact, it would be very surprising if they didn’t. But at the moment we don’t know exactly what they were — and even if we did it would be difficult to say how much specifically genetic changes explain, because as the authors point out, genes and culture evolve together in a flywheel effect.

Say you have a society that thinks the most high-status, badass, and manly thing you can do is excel at Call of Duty. Among these people, women go looking for gamer husbands and cheat on their jock boyfriends with guys higher on the league rankings, and fathers who are good at quickscoping have more resources to invest in their children — all of which obviously creates strong selection for hand-eye coordination and quick reflexes. Soon Call of Duty doesn’t cut it any more: the newly acute senses demand increasingly challenging games of skill, children are drilled from an early age to minimize their response times, and culture centers ever more on activities that benefit from speed and precision. Selection intensifies, people get even better, institutions and values grow up around reflexes and coordination…and eventually you’ve got a population that’s meaningfully better at this stuff than their ancestors. Now say a solar flare fries all the electronics and plunges the earth back into the Stone Age. When the descendants of the Call of Duty players hunt deer a lot more effectively than their neighbors (whose fathers’ fathers played Factorio), is that genes or culture?

Of course, the flywheel could get started the other way, too: preexisting genetic variation might make some populations more susceptible to a new memeplex than others. (I would not be shocked if it turned out that societies that are more WEIRD had a higher frequency of some particular neurological gene variant than other, equally complex and sophisticated, societies, though Lord only knows what it is.) Culturally-contingent selective pressures play out in ways that are more complicated than “be resistant to malaria”: if being the smartest person in your village makes you more likely to head to a big city where you get tuberculosis and die at thirty, how much selection for intelligence is actually happening here? In fact, on a population level, the last three generations of American life seem to be selecting for ADHD and against cognitive performance and educational attainment. (Thanks to Steve Stewart-Williams for the summary and reproducing the below chart, because the paper in question is not available from my totally reputable, legitimate, and patriotic sources.)

Cochran and Harpending open their first chapter with a quote from Stephen Jay Gould, who wrote: “There’s been no biological change in humans in 40,000 or 50,000 years. Everything we call culture and civilization we’ve built with the same body and brain.” The rest of the book is spent demolishing his claim and arguing (quite convincingly) that the flywheel of genetic and cultural coevolution has been one of the key driving forces of human history and needs more attention from social scientists of all stripes. (Also historians and frankly philosophers too.)

But however convincing it may be, their case becomes wildly unpopular as soon as they move from traits like height or blood type or Duffy negativity, which we think are morally neutral, to things like intelligence, conscientiousness, rule-following, and ability to delay gratification. The people who don’t like this conversation fear — frankly, with some reason — that it’s a mere hop, skip, and a jump from “population X has a higher frequency of gene Y, which makes its bearers worse at planning for the future and leads them to make sub-optimal choices” to “population X are bad, irresponsible people and you should never trust them.” And yet, if population X actually does have a higher frequency of poor-planner genes, that would be useful information if you were trying to figure out why they tend to have more credit-card debt, just like knowing that some groups are really short helps explain why they don’t show up in the NBA. If you don’t confront the world as it really is, nothing you do will produce the effects you want.

But the people who don’t like this conversation have another fear, too. They’re afraid that the world in which they personally excel (because, come on, it’s not the downtrodden dregs of society who are getting mad about human genetics research) is fundamentally unfair, that the way things turned out isn’t because some people worked harder or deserved it more, or because some bad guys went and did bad things, but just…because.

Argument Against Jared Diamond Factor: 10/10

Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle, Daniel Everett (Vintage, 2008).

I was promised an ethnographic study of a particularly dysfunctional “small-scale society” and instead I got this weird mélange of academic linguistics paper and personal memoir, half counter-example to Chomskyan universal grammar and half Protestant missionary losing his faith. But the raw material for both, Daniel Everett’s time spent with a hunter-gatherer tribe in northwestern Brazil, is fascinating, and the book I thought I was going to be reading turns out to be in there after all. It’s just hidden between the lines.

In 1977, Everett and his wife Keren took their three children (then seven, four, and one) and moved to the Amazonian jungle. They had been sent by SIL, an evangelical Christian nonprofit that trains missionaries in linguistic fieldwork, and their job was to study and document Pirahã, a notoriously difficult language isolate spoken by a few hundred Indians along the Maici River in Brazil’s Amazonas state. Once they had learned enough of the language, they were supposed to use it to produce a new translation of the New Testament. (SIL forbids its missionaries from preaching or baptizing: their role is one of translation and language preservation, on the theory that the Word of God will speak for itself.) Of course we’ve seen one of the problems with this: translating a whole complex of ideas to a radically different cultural context is extraordinarily difficult. (And even more fundamentally, the Bible is not self-interpreting. Don’t at me, Protestants.) But Everett faced even more basic difficulties in his project, even aside from the intrinsic dangers of the Amazonian rainforest. One, the Pirahã language is profoundly strange. And two, the Pirahã people had zero interest in becoming Christian.

First, the language. I should note here that everything Everett says about Pirahã (which speakers call Apáitisí, “straight head,” as opposed to foreign languages which are “crooked head”) is incredibly controversial, and that some linguists who have analyzed his recordings and other records disagree with his conclusions (see this, for example). Still, he’s the acknowledged expert on the topic and the source of basically everything professional linguistics knows about it, and frankly I’m reviewing his book and not Noam Chomsky’s, so…I report, you decide.

Anyway, according to Everett, Pirahã is a really weird language. It has only ten phonemes, but it’s so tonal and reliant on accent and emphasis that it can be whistled with no phonemes at all. More importantly, though, it doesn’t have many of the features that linguists have long assumed are universal. There’s no phatic communication, expressions that don’t convey information but are meant to establish or maintain social relationships (“how’s it going?” is usually not an actual question). There are no comparatives. There are no words for color: if you want to say something is red, you can say “this is like blood.” There are no numbers or counting words, and there are no quantifiers (each, every, all). And the big one: there is no grammatical recursion. Pirahã can’t embed one phrase inside another, like “the man who is tall came into the house,” though it can express the idea by saying something like, “The man is tall. The man came into the house. They are the same.” This last one was an absolute bombshell to the linguistics world, because Chomsky had made recursion the centerpiece of his theory of universal grammar, and Everett has quite a lot to say about their arguments. If you’re interested in the details you should read the book because I’m not.

But Everett had noticed something else: the Pirahãs were also culturally weird. Their material culture is incredibly simple. They have virtually no sense of aesthetics: their adornments are asymmetric and utilitarian, intended to scare away spirits in the forest. If they need baskets, they make them on the spot out of wet leaves which will dry and crumble after a day or two rather than using the more durable materials that are equally available. They know how to salt or smoke meat, but they don’t. They have no myths and no rituals for marriage or death. Once the Pirahãs asked Everett to buy them one of the sturdy dugout canoes made by their Brazilian neighbors, which they preferred to the bark canoes they built themselves. Instead, he hired a Brazilian to teach them to do it:

After about five days of intense effort, they made a beautiful dugout canoe and showed it off proudly to me. I bought the tools for them to make more. Then a few days after Simprício left, the Pirahãs asked me for another canoe. I told them they could make their own now. They said, “Pirahãs don’t make canoes” and walked away. No Pirahã has ever made another [dugout canoe] to my knowledge.

It goes beyond that: the Pirahãs rely on imported steel tools, especially machetes, for much of their work, trading for them whenever possible. And yet, Everett writes, “The Pirahãs do not take good care of them. Children throw new tools in the river; people leave the tools in the fields; and often they trade tools away for manioc meal when outside traders make their way in.”

After some consideration, Everett concludes it’s a cultural value among the Pirahãs not to think or talk about anything beyond immediate experience. The Pirahãs do not plan for the future or talk about the past. They have no words for numbers or colors because those are abstractions, and they don’t say things like “who is tall” because it isn’t anchored to the moment in which they’re speaking. They’re happy to work at the dugout canoe under their teacher’s supervision, but they have no interest in further hard work even if it would benefit them in the future. And of course they have no interest in becoming Christians: they aren’t concerned with truth, or transcendent reality, or the afterlife, and they would prefer to continue drinking alcohol and having sex with whomever they like.

Everett clearly loves the Pirahãs and their little corner of the rainforest. (In the 1980’s he was involved in getting the Brazilian government to legally recognize it as a reservation.) He paints a beautiful picture of the land and the people even as he tells harrowing stories about things like his awful trek to get medical care for a wife and daughter dying of malaria. But the book is a truly bizarre document, with Everett repeatedly telling us how wonderful the Pirahãs are, how happy and peaceful their lives, and later undercutting it with details. He writes that they respond to each other with “patience, love, and understanding” and see themselves as “a family in which every member feels obligated to protect and care for every other member,” and also recounts a story of a father murdering his own premature baby. He tells us that “violence against anyone, children or adults, is unacceptable to the Pirahãs” and then mentions in passing an encounter with an old man, Hoaaípi, who “had a fresh arrow wound from another Pirahã, Tíigíi” or drops a parenthetical like “(Keren witnessed a gang rape of a young unmarried girl by most of the village men.)” He says the Pirahãs “won’t let another Pirahã starve to death or suffer if they can help” but tells this story from a previous missionary:

Steve Sheldon told me about a woman giving birth alone on a beach. Something went wrong. A breech birth. The woman was in agony. “Help me, please! The baby will not come,” she cried out. The Pirahãs sat passively, some looking tense, some talking normally. “I’m dying! This hurts. The baby will not come!” she screamed. No one answered. It was late afternoon. Steve started toward her. “No! She doesn’t want you. She wants her parents,” he was told, the implication clearly being that he was not to go to her. But her parents were not around and no one else was going to her aid. The evening came and her cries came regularly, but ever more weakly. Finally, they stopped. In the morning, Steve learned that she and the baby had died on the beach, unassisted.

Of course, anyone who spends enough time among another people will become fond of them. It doesn’t even need to be in person — histories of the Aztecs or the Carthaginians demonstrate exactly the same kind of “sweeping positive statement / truly horrific details” phenomenon. So it should be no surprise that after spending thirty-odd years among the Pirahãs, Everett comes to like and respect them and to want us to do the same. The surprising part is that he decides they’re right.

He questions, he wonders, and he ultimately decides to reject not only his faith in God but the “delusion of truth”:

God and truth are two sides of the same coin. Life and mental well-being are hindered by both, at least if the Pirahãs are right. And their quality of inner life, their happiness and contentment, strongly support their values.

It took Everett decades to finally come out as an atheist, and when he did his wife divorced him. Two of his three children cut off all contact.7 (It’s not clear to me how much of this was over him no longer being Christian as opposed to him lying for years about his most fundamental beliefs; I could buy it either way.)

Like all conversion stories, Everett’s is wildly unsatisfying from the outside. He never really shows us why, perhaps because he can’t. And yes, the Pirahãs’ relentless cultural and linguistic focus on the present seems very strange to us (even as it goes a long way to explaining why they live in a few tiny villages in the jungle), but the strangest is Everett’s embrace of it. Ultimately it’s the man from my own society who proves the most foreign.

Argument Against Jared Diamond Factor: 7/10

This was obviously summer privilege, there is now plenty of coughing and sneezing in my house.

Also the only one I’ve read.

For some reason Harper insists on referring to “tree thinking” in place of phylogenetics and using “time travel” for paleogenomics, but he relies heavily on both.

The strain of tuberculosis found in the Americas before 1492 is descended from a strain usually found in seals, who presumably got it from other aquatic mammals, who got it from humans in the Old World. The Columbian Exchange, but for whales.

Razib Khan has an excellent summary of this paper here.

His son Caleb, who was a toddler when they first went to the Amazon, is now a linguist and anthropologist who has done his own fieldwork among Pirahãs.

I made this comment originally on another book review of the Everett Pirahã book (lightly edited):

Gwern has a great book review on this one: https://gwern.net/review/book#dont-sleep-there-are-snakes-everett-2008. The ending of Gwern's review brings up probably the best theory I have read to explain the Pirahã, although I would put it more bluntly: maybe they are just extremely inbred and very dumb. They can't plan for the future the way some children cannot plan for the future. They cannot learn how to count to ten, because that is too complicated for them.

The *New Yorker* article (cited by Gwern and found here https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/04/16/the-interpreter-2) also implies that the Pirahã are really dumb. An evolutionary biologist, William Tecumseh Fitch (yes, he is a direct descendant of the American Civil War general), traveled down there to test the Pirahã, and he had a lot of problems getting them to pass basic grammar test which apparently even all monkeys tested could pass. According to the article, Fitch eventually found one sixteen-year-old who could pass the test. I cannot figure out from Fitch's Google Scholar page where he wrote up these results--maybe they're buried somewhere.

Getting genetic samples of the Pirahã would clarify how inbred they are, and it would at least partly let us guess their genetic IQ, insofar as we can use one of those fancy polygenic scores for educational attainment/cognitive ability to estimate it. I also would like to see someone replicate Everett's work (Margaret Mead's fieldwork did not replicate). Even the *New Yorker* journalist had to rely on Everett's translations.

Per Wikipedia, "[Everett] says that he was having serious doubts by 1982 and had abandoned all faith by 1985." And wouldn't you know it, he completed his masters thesis in 1980 and PhD in 1983 in linguistics under a Brazilian-French advisor. His thesis provided "a detailed detailed Chomskyan analysis of Pirahã." Anyways, it sounds like he begins to reject his faith as a Brazilian graduate student in a (presumably) atheistic/secular atmosphere.

Incredibly, Everett is an avowed defender of the blank state.

as a fellow snorter of Hajnal lines, I thank you.