REVIEW: The Hard Thing About Hard Things, by Ben Horowitz

The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers, Ben Horowitz (Harper Business, 2014).

Way back when the world was young, when men were men1 and before the corners of the maps even had cute illustrations of dragons in them, a young man with above-average competence and ambition had a straightforward path to glory. All he had to do was round up a few dozen of his closest friends and form a kóryos, and then go raid and pillage a neighboring village. If he was lucky it’d go well, and the survivors would carry off some women and some easily transportable forms of wealth, and then sit around and tell stories about how awesome they were.2 If he was really lucky and repeated this feat a few times, then the whole enterprise might begin to snowball. His dozens of friends would turn into hundreds of friends, and soon he’d be laying waste to entire regions and later generations would memorialize him as an ancestral spirit or war god.

Yes, life was simple back then. Then along came states — of many different sorts, but what they all had in common was brutal and efficient punishment for any sort of brigandry. Not to worry though, there were still opportunities for the young man of uncommon energy and hunger. If he lived during a period of collapse or retrenchment, a career in petty conquest of his neighbors might still be open to him. If, conversely, he lived during a period of imperial expansion, then he could lead an expedition, either publicly or privately-funded, out into the corners of the map (which by now were adorned with adorable pictures of dragons), and plant the flag of his fatherland upon the still-twitching bodies of the natives.3 Out there, somewhere else, life was a bit more free-wheeling and Hobbesian, more amenable to ultra-rapid advancement for a young man with more talent than class.

More time passed, and the dragons disappeared again. The corners of the map got entirely filled in, and then every last bit of land got shaded in the color of some basically-functional nationstate. What now, for the young man who had won the genetic lottery but not the social one? In times of peace, militaries become bloated with careerists and aristocratic failsons, but give them a salutary stretch of war and they quickly revert to lean, mean, meritocratic machines. We see the same basic pattern recur in conflicts as different as the American Civil War, World War II, and the Russo-Ukrainian War: an initial phase in which one or more armies are commanded by blundering incompetents, a transitional phase in which the incompetents are rapidly killed off or forced to retire, and a terminal phase in which the battlefield is controlled by dead-eyed men of ignoble origin and impressive ability.4 And so it is that the army seemed like a natural place for a Napoleon Bonaparte, or for any other intelligent, sensitive, ambitious, frustrated young man.

Okay, but now imagine that you live in a globe-spanning hyper-empire that has ushered in an era of incomparable peace and prosperity. Can you imagine somebody like Napoleon or Alexander or Genghis Khan joining the US Army today? Like, the army with all the powerpoint slides and DEI consultants? It’s inconceivable. Laughable, even. For a time, there was a lively debate within the Psmith household about where the bulk of these men do end up in our civilization, but then a guy named “Big Balls”5 took over the United States government and the answer became obvious. The answer is startups.

This insight answers a number of mysteries about the world, like: why it is that management books and military strategy books sound so eerily similar? Or why it is that if you read a war memoir and let your eyes lose focus like you’re doing one of those Magic Eye puzzles, you suddenly find yourself reading a business memoir? To be sure, war and business are very different activities, but they attract a similar sort of personality. This was especially true back when war was a more independent and entrepreneurial affair, as it was when most of the great military classics were written.

Every society offers official avenues of advancement that look like a complex game with byzantine rules, a cross between a ballroom dance and one of those incredibly fiddly board games. Most people take the deal: they put energy and excellence into learning all the moves, all the weird interactions and all the exceptions. But actually, the game is for show. The true game that moves the wheels of history is Nomic.6 Some people break through to this new level of reality after a long and distinguished career of a more conventional sort; others hear it as boys in the call of the kóryos. Both war and business, at least in their rawest and most elemental forms, offer direct manipulation of this deeper layer of the simulation. Rather than pour your ingenuity and craft into brilliantly following the rules set by others, you aim to brilliantly devise new rules and new scenarios and a new playing field that ensure you always win. This obviously isn’t quite true in the civilized world, where military commanders and entrepreneurs alike have to obey certain laws, but the flavor of it remains.

The other similarity between war and business, the central paradox that they both share, is that while they are on some level a free-for-all where the only thing that matters is winning, the actors in the mêlée are not individuals but complex, hierarchical organizations. This means that war books and business books don’t just have authors with similar psychological profiles, they have largely overlapping subject matter too. In either arena, you must master the craft of welding men into a titan whose skin and muscles are individuals, whose bones are loyalty, and whose tendons are ambition. At the smallest scale, this looks like charismatic leadership in the Weberian sense. At the very largest scale, it looks like institutional design and incentive alignment…plus a healthy dose of charismatic leadership.

This also explains why most war books and most business books are useless.

The basic problem is just the recurring one that “process knowledge” cannot be losslessly converted into a propositional form suitable for writing down. Imagine reading a book by Jascha Heifetz about playing the violin and then thinking that you knew something about playing the violin. I hammered this point to death in an old review of a very bad book about business, so go read that if you want to hear more about it. You might object that large parts of the art of leading men to victory actually are propositional, but that runs into the other point I belabor in that review I linked above: every army and every company is different, and the situations they find themselves in are different too. As with parenting, so much of the skill of leadership is not about dealing with people in the abstract but dealing with these particular people in this particular situation. The same is true of strategy and tactics, which are less about memorizing a particular set of gambits and more about learning to rapidly assess the situation and come up with a winning move. What this means is that it’s hard to get more specific than Cambyses’ advice to Cyrus: “Just be incredibly good at whatever it is you do.”

But what if there were a business book that leaned into this rather than hiding from it?

I want to be very clear that I went into this book preparing to hate it. Some reasons for that include: (1) an old mentor of mine once told me that Horowitz had nothing important to say, (2) the book got so popular that it became a bit of a cliché and a dreary pillar of the startup-industrial complex, and (3) Horowitz begins every chapter with a set of gangster rap lyrics as epigraph.7 So there I was, preparing to hate the book, and then I flipped to the first non-introductory chapter and read these words and knew that I would love it:

People always ask me, “What’s the secret to being a successful CEO?” Sadly, there is no secret, but if there is one skill that stands out, it’s the ability to focus and make the best move when there are no good moves. It’s the moments where you feel most like hiding or dying that you can make the biggest difference as a CEO.8

The book begins with an accelerated narrative of Horowitz’s childhood and early career where he tells outrageous stories, like the one about the time he started a fist fight at a pickup basketball game because somebody insulted his brother, and received a gruesome black eye, and then talked his now-wife out of standing him up for their blind date. He ends each story with a solemn bit of business-speak like, “and that’s when I learned about optimizing synergies.” I assume this is total deadpan performance art and a send-up of conventional management books, but it’s actually even funnier if it isn’t.

Even here, though, we get glimpses into the soul of the author, and into the deeply countercultural message of this book. Why did he start a fistfight? Because somebody had disrespected his brother, because blood is thicker than water, because it is the job of the strong to protect the weak. Why is it important that his wife went on the date? Because calling it off would have been disrespectful, because it would have shown that she could not keep her word — and she went on the date because she is a woman who keeps her word and who respects him. That’s right, it’s honor culture…

…and suddenly the rap lyrics start to make more sense. Black people have their own distinctive culture of honor, inherited with some modifications from that of the antebellum South and from the Scots-Irish of Appalachia who have fought and won almost all of America’s wars. Horowitz is a nerdy Jewish guy with communist parents, but he grew up around black people, and imbibed through them the Scots-Irish mindset, and through them the gloriously premodern ideology of the Iliad: show off your strength, keep your promises, kill anybody who makes you look like a chump, protect your honor. This is not a book about how to succeed at business, but a book about how to be and become a certain kind of man.9

Horowitz believes that apart from virtue being its own reward, this kind of man will tend to win. That’s partly because he will be respected, feared, etc., but mostly because this kind of man is willing to endure unimaginable stress and suffering in pursuit of his goals. A founder/entrepreneur in the Horowitz vein is the opposite of the bureaucratized domain-agnostic professional managers that run most of corporate America. His name is on the building, his family and friends have invested their life savings in his company, he has promised every person he hired that he will protect them and fight for them in exchange for their loyalty, and when times get tough he can’t just walk away — because to do so would be to lose his honor. It would mean betraying everybody who ever trusted him, and the man of honor would rather die than do that, so he will work until he wins or dies.

In The Managerial Revolution, James Burnham wrote about the transition from an economy full of small-scale owner/proprietors to one dominated by a technocratic managerial class directing productive resources owned by others. We call both these systems “capitalism,” but Burnham points out that they’re actually completely different. For one thing, the professional managers are interchangeable, and they view the companies they work at as interchangeable. It’s Claire Hughes Johnson-ism. Conversely, the petty proprietor, like the startup founder, is “all in”: his name is on the door of his small business, he has backed it with personal loans, he cannot just pick up and head over to another corporation and keep his career.

Economic historians consider the transition from small owner-operated businesses to modern manager-run corporations to be one-way and in the past. But the tech world has brought back the old model on a grander scale. Of course we recognize that startup founders have vastly more internalized consequences of success and failure. (If a professional manager makes a transformative impact to his business, he will get a nice bonus, but he will not make billions of dollars like a founder. If a professional manager totally screws something up he might need to change jobs, but he will not be ruined like a founder.) But what Horowitz tells us is that the highest reaches of Silicon Valley have also brought back a much older culture and ethos as well. It’s non-WEIRD, obsessed with personal glory and honor, governed by “thick” social attachments and personal ties of loyalty. This instantly explains the massive cultural gulf between tech company CEOs and the vice presidents one or two levels down.

Horowitz believes the ability to endure, to survive, to chew glass, and then to laugh and ask for more, is especially valuable in the tech industry because it’s so unpredictable and changes so quickly. Fortuna’s wheel turns dizzyingly fast in tech: the exalted are quickly humbled, and those in the gutter suddenly discover that they’re sitting on the key technological enabler of whatever the new fad is. So the overriding directive is — survive. Figure it out. One more day. Okay, now one more day again. Never surrender. One more day could bring the relief army riding over the horizon, the technological breakthrough or the acquisition offer or the market zeitgeist change. You just need to sit in this trench and keep the enemy at bay for one more day. Tomorrow might bring news of peace. It will all have been worth it, brothers! Come on, let’s just make it one more day.

When you are sitting in that trench, and the bombs are falling all around you, your only objective is to figure something out. If Horowitz believes one thing, it’s that: “There is always a move.” He practices what he preaches. At the nadir of the dot-com bust he was unable to raise money in private markets, so he took his failing company public. When he needed one particular deal to stay in business and the guy in procurement on the other side said there was no way in hell he would do the deal, he found out what that guy’s favorite product was and with his last money bought the company that made it and integrated it into his own. There is always a move. This is the central article of faith for Horowitz, as it has been for most victorious generals. If you think all roads lead to defeat, you aren’t thinking hard enough. There is a move that keeps you alive one more day. There must be. Find it.

Sometimes the only move that keeps you alive is to lay off 80% of your staff. Yes, you need to do it. Personally.

People won’t remember every day they worked for your company, but they will surely remember the day you laid them off. They will remember every last detail about that day and the details will matter greatly. The reputations of your company and your managers depend on you standing tall, facing the employees who trusted you and worked hard for you. If you hired me and I busted my ass working for you, I expect you to have the courage to lay me off yourself.

I had never read sentences like that in a business book before, but this is not a business book. It’s a book about honor. You must lay them off yourself because to do otherwise would be despicable. It would mark you forever as a dishonorable coward, and that in turn would taint your company, your associates — everybody who ever trusted you. You would heap ignominy upon ignominy, adding to your betrayal of the fired employees (which now cannot be helped) the betrayal of those who lent you reputational capital at any step along the way. Dishonor pollutes everybody who ever loved you, and by extension the people who loved them. This is a harsh creed, but it certainly gives you a reason to behave correctly. And part of behaving correctly is confessing your failure.

Going into a layoff, board members will sometimes try to make you feel better by putting a positive spin on things. They might say, “This gives us a great opportunity to deal with some performance issues and simplify the business.”… do not let that cloud your thinking or your message to the company. You are laying people off because the company failed… The message must be: “the company failed and in order to move forward, we will have to lose some excellent people.” Admitting to the failure may not seem like a big deal, but trust me, it is. “Trust me.” That’s what a CEO says every day to her employees. Trust me: This will be a good company. Trust me: This will be good for your career. Trust me: This will be good for your life. A layoff breaks that trust. In order to rebuild trust, you have to come clean.

Horowitz thinks you need to be honest with your employees all the time, not just during layoffs. I mention this because it is a stark contrast with the conventional wisdom peddled in management texts. When I began reading this book, I thought Horowitz was the anti-Claire Hughes Johnson because he does not believe in domain neutral expertise, only domain neutral honor and character. But actually he’s the anti-CHJ because he believes in telling people the truth. The phrase that made me go absolutely ballistic when reviewing Scaling People was, “Leadership is disappointing people at a rate they can absorb.” Horowitz believes that leadership is disappointing people all at once. Or as he puts it: “If you are going to eat shit, don’t nibble.” In the section covering this he provides many very good and practical reasons why this is actually in your interest. I believe all of them. But don’t be fooled, this is not why he is telling you to do this. He is telling you to do this because he wants you to preserve your honor.

Does this job sound stressful? We actually haven’t gotten to the stressful part yet. The fundamental job of a CEO is to make a continuous stream of high-stakes decisions, while maintaining excellent quality of decision-making, despite not having time to think properly about any of them. “Oh no, they’ll experience decision fatigue.” Yes, but they need to suck it up and produce a constant stream of excellent decisions at a very high decisions-per-second anyway. This is actually still not the stressful part. The stressful part is that if the CEO is doing his job well, every single one of those decisions will be among the most painful or agonizing or otherwise difficult that he has ever made.

The person who first explained this paradox to me was Byrne Hobart at the Diff. Consider a one-person company. That one person is making all of the decisions. Some of them will be easy, like what to order for lunch. Some of them will be hard, like whether some major change in strategy is a good idea. But in the course of a normal day, most of the decisions that lone person faces are easy, with a few hard ones mixed in.

Now imagine that this person hires somebody to work for them, and imagine that they do a good job delegating. The underling is now in charge of some part of the business. He or she is making a share of the decisions in that area. If the delegation went well, the underling can make all the easy decisions themselves, but for the really tricky cases…well…maybe they should ask their boss’s opinion. So the boss is getting a filtered set of decisions disproportionately biased towards the hard ones. You may think that’s okay, because they are also making fewer overall decisions but ahh…the delegation went well, so the business has grown, so there are many more decisions to be made per day. The boss is making as many decisions as ever, they’re just harder on average, instead of the equal mix they had before.

The CEO of a large company sits at the limiting case of this process after it has taken many, many, many more steps. A large company can process a vast number of decisions per second. A huge majority of them are handled by frontline workers, and they pass the ones that are a bit above their pay-grade on to their bosses. Those bosses maybe handle a bunch of the medium-difficulty decisions, and pass the truly tricky ones another step up the chain, and so on. So the CEO receives a highly filtered and selective stream of the worst imaginable decisions. And again, this is in the happy case where they have done a good job delegating and therefore their company is able to grow. Enjoy.

The odd thing about this burden is that it’s once again curiously like being a soldier. A soldier friend of mine once told me, “To be a junior officer is to have the power of life and death over every living thing within artillery range.” That sounds like its own special kind of decision fatigue hell. But the thing is that wartime is an exceptional condition that everybody recognizes as exceptional. CEOs look like normal people. I have friends who are CEOs. You would not know what their jobs were unless you asked them. It’s like how there are some horrible diseases that get you tons of public sympathy, and other horrible diseases that get you none at all. There is something weird about there being people who are walking around, experiencing something akin to battlefield conditions all the time, but who look totally normal on the surface.

I can already hear you saying, “Boo hoo, do the big scary CEOs have their feelings hurt that they’re not appreciated? Nobody cares.” And Horowitz has already anticipated your critique. He agrees with it. He has an entire chapter titled “Nobody Cares.” Again, the comparison to a military commander is illustrative. Did your entire army catch Dengue fever and your logistics train get destroyed by freak floods and your enemy is suddenly getting supplied advanced weapons by another country? Nobody cares, bro. Just figure out how to win. You literally have one job. A general who barely lost when heavily outnumbered, or a startup CEO who almost made it, might be an impressive person in some objective sense. But nobody cares. History’s verdict will be, “Loser.” That’s the rule, and it comes with the job title. Nobody cares.

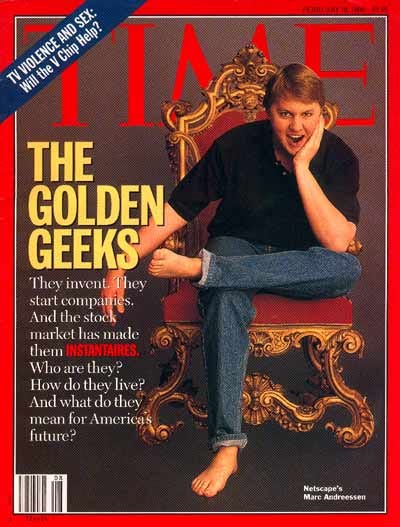

After eight heart attack-inducing years, Ben Horowitz finally sold his company. He and some of his surviving employees made a moderately enormous amount of money, and as he looked around and wondered what to do next he knew that the answer would be: not starting another company. But it seemed an awful shame to let all the hard-earned wisdom he’d accrued just rot away inside his head, so he called his old boss and friend Marc Andreessen and the two of them discussed their dissatisfaction with the venture capital scene. Most of the VCs were finance bros with no experience running companies (this is still 100% true, by the way) and a condescending attitude towards the founder/CEOs they backed. Horowitz remembers one particularly deflating instance when a famous venture capitalist asked him, in front of his team: “When are you going to get a real CEO?”10

And so was born Andreessen-Horowitz (better known as a16z), a venture capital firm with the innovative new premise of helping founders build good companies. When the firm was founded, they were the enfant terrible of startup finance, and even when this book was written, they were elite and hip. But since then something strange has happened. They’ve been successful. So successful that they started raising enormous amounts of institutional capital, which they then needed to find a way to deploy at scale.11 The result is that they’ve turned into what a friend of mine once termed “the Wal-Mart of startups.” What an odd mirror of the process that happens to every successful startup as well — young companies are all quirky and weird in their own way, but big and successful ones all look much more similar.12

But maybe the former renegades have one more trick left in them. You can interpret Andreessen’s Time to Build manifesto, and his subsequent involvement with the Trump administration, in many ways, but I view it as an attempt to reverse Burnham’s managerial revolution more broadly. Silicon Valley was a refuge for an older and more vital form of capitalism which had almost gone extinct everywhere else. Now Andreessen and Horowitz are trying to bring that updated model of owner/proprietorship back to the rest of the economy. If they succeed, both a cause and an effect of it will be a new elite. And not just a new elite, but a new kind of elite, with a very different set of preconceptions and values. Less interested in consensus, less averse to conflict, touchier about their honor, more personally loyal, more prone to grand displays. They will seem more like the military men of the nineteenth century and less like the corporate leaders of the twentieth century. Less Jack Welch, more Elon Musk.

For millennia, a young man of uncommon energy and ambition had many ways to achieve his dreams. For a few terrible decades, the only thing he could do was become a tech bro. But the nature of the kóryos is that as it succeeds it grows, and now the mounted hordes are poised to spill across the rest of the economy. Do you feel the thunder of the hooves? Do you hear the baying of the dogs? History is starting once more, and we may find that the long twentieth century was not the future, but an interlude. A dream.

I mean this literally. The population-wide decline in serum testosterone levels is significant, broad-based, and very mysterious. I wrote a little bit more about the consequences of it in my review of Boom.

While writing this I was suddenly very powerfully struck by the memory of my own adolescent hijinks. These were a good bit tamer than those of a teenage Indo-European warrior band, but what amazes me is that we talked about them in the exact same self-congratulatory register of epic accomplishment that you see in Beowulf, or the Iliad, or the Norse sagas, or the Siege of Slavyansk, or gangster rap. There’s been a lot written about how, across times and places, adolescent males seem to feel a common urge towards doing stupid and violent things. But what I really want to read is a comparative literary analysis of how they brag about their deeds.

By this I don’t just mean the Age of Exploration and its analogues. There were plenty of times that less-advanced peoples came and conquered more-advanced peoples too, from the Crusades to the steppe invasions. The point remains that you can get away with more entrepreneurial behavior when you’re doing it to foreigners.

This is one reason that the board game/computer game model of attritional warfare isn’t accurate. Most armies get stronger and smarter as they take losses, until very close to total defeat.

What makes it perfect is that not only does Coristine’s background and profile fit that of a teenage warlord almost perfectly, his nom de guerre is charmingly premodern as well.

Yes, the financial system is also Nomic.

That last item in particular seemed indescribably cringe, even when you remember that Horowitz grew up around black people and married into a black family. But as we will see, it turns out to be extremely apropos…

He continues:

In the rest of this chapter, I offer some lessons on how to make it through the struggle without quitting or throwing up too much.

While most management books focus on how to do things correctly, so you don’t screw up, these lessons provide insight into what you must do after you have screwed up. The good news is, I have plenty of experience at that and so does every other CEO.

One of the single most irritating things about this book is that Horowitz sometimes uses female pronouns for the generic third person. Okay, we get it dude, you’re a super-mega feminist. But (1) that is not the convention of the English language and (2) it totally undermines his message, because the particular activities and particular virtues he’s describing are distinctively masculine. You can’t actually gender-swap “separates the men from the boys” and have it mean the same thing.

I’m mildly surprised, given the code of HONOR as exemplified by the Iliad, that that venture capitalist did not go home with a black eye that day.

I had planned to put a link here to a very insightful article I once read about the rise of mega-funds and the increasing consolidation and returns to scale in the VC industry, but I can’t find it. If somebody puts a good link in the comments, I will update the post. Thanks!

The most charitable explanation for this is convergent evolution: growth-stage companies come under enormous amounts of pressure, and there are certain corporate forms that do just work well at scale, like how everything becomes a crab.

The less charitable explanation is mimesis.

Important to remember that while war and business have some similarities, they are fundamentally different domains.

There's a reason America's best warriors are the Scots-Irish of Appalachia and her best businessmen were Yankees and Quakers.

It's also notable that during the Civil War it was the Yankees who won; in modern war, logistics and industrial production beats warrior spirit.

I’ve been running through an MBA for the past couple years; and one of the things I’ve come to learn is that much of MBA literature lives or dies on whether a given manager has the guts to hold accountability for a decision.

In sufficiently strong hands, Porter’s Five Forces map is a clarifying battle map—what are we, and what are we not? But in the hands of a spineless manager, that same tool allows the manager to pin downside risk on some McKinsey suits.

I wonder if a core mistake of MBA thinking is assuming anyone can become a leader without eating shit—and the lie continues because at this point an “honest” management consultant would judge most of their clients as personally unworthy to lead.