REVIEW: The Everlasting Empire, by Yuri Pines

The Everlasting Empire: The Political Culture of Ancient China and Its Imperial Legacy, Yuri Pines (Princeton University Press, 2012).

During the previous round of US-China diplomatic tensions, a friend who works in public policy sent me a Signal message: “John, I don’t mean this in a racist way, but can you explain to me why there are so many Chinese people?”

Stated like that the question does sound a bit mysterious, but let’s see if we can reframe it. Prior to the demographic transition, each chunk of the earth’s surface had a certain biological carrying capacity. If we act like Vaclav Smil-style autistic alien robots, we can work out that number from first principles (assuming a given technology level). The region we call “China” is big, and much of it is arable, so it can support a lot of people.

Places like Europe and Africa can also support a lot of people, but the people in those places don’t have a homogeneous political and ethnic identity. So then the real question is why the region we know as China came under the control of a single nation and ethnos — and why, moreover, that nation’s occasional political fragmentation never led to an enduring cultural fragmentation (as happened after the fall of Rome).

All of the standard answers to this question seem to revolve around geography. I’m told the accepted one in academia is that most civilizations arose around one major river valley but China arose around two, which somehow changes everything for some reason. Jared Diamond’s theory is slightly less dumb: he argues that the wide-open geography of the North China Plain and the excellent transport afforded by inland waterways made it inevitable that one political entity would always dominate the region, while Europe’s natural barriers made it possible for small nations to maintain their independence.

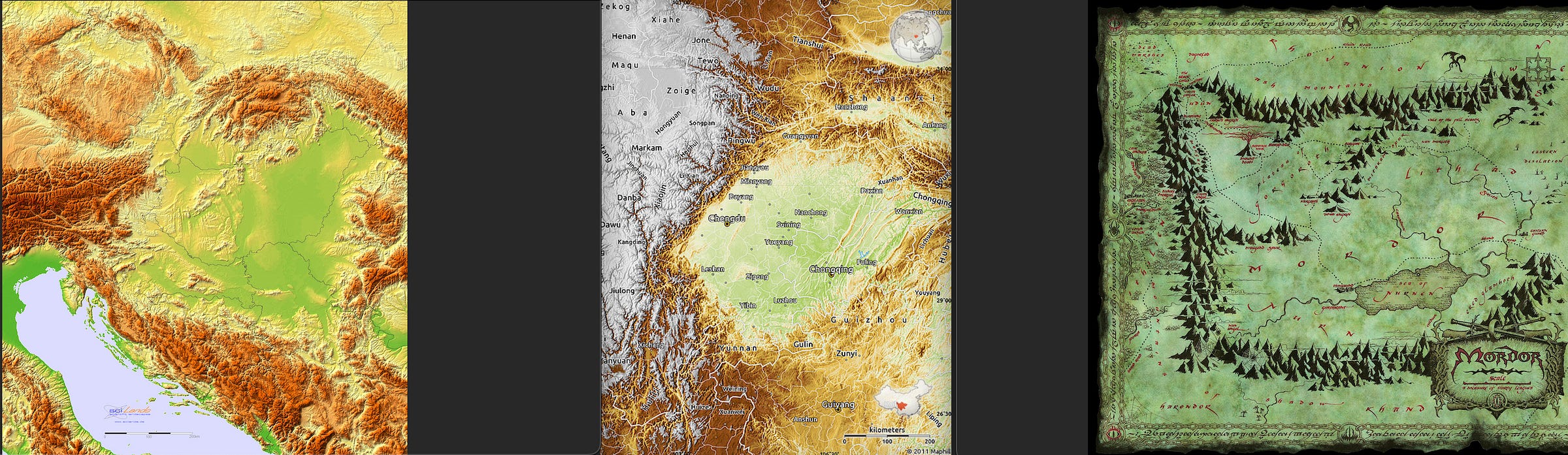

Well I hate to pile on since Jane has just written a whole thing about how Jared Diamond is always wrong, but seriously bro? Have you ever been to Southern China? It’s a thousand tiny sheltered valleys and coastal refuges, so criss-crossed by mountain ranges that even today their spoken languages are mutually unintelligible. And yet, they’re Chinese. Or how about the Sichuan Basin? Look at Sichuan on a topographic map and it looks like Mordor, or if you prefer, like the Pannonian Basin in Central Europe, which got settled by the Magyars and developed into the ethnically distinct nation of Hungary. And yet, the residents of Sichuan are Chinese. And about those great rivers… Rivers are great for trade and transit of goods, but they’re also obstacles for armies. Sure enough China was divided into Northern and Southern kingdoms numerous times by the Yangtze River or by the Huai River, both of which served as massive defensible barriers. And yet, the division never lasted, the empire reunited, and both Northern and Southern Chinese, while they have real cultural differences, are Chinese.

Anyway, this is the question that Yuri Pines is here to answer, and he approaches it the way Bernard Yack would. That is to say, he ignores geography, ignores genetics, ignores climate, and ignores every other sort of material condition that could explain China’s unusual endurance as a cohesive political and ethnic entity. What if, he says, it’s actually entirely about ideas? Memes turn the wheel of history, so could it be memes that hold China together? To answer this question we need to go back, way back, to the time that all the Chinese memes come from. Yes, I am speaking of the Warring States Period.

The other reason to look at the Warring States Period for clues is that it was the first major occasion on which China violently flung itself to pieces. This is important — there’s a stereotype which says that China has existed in placid stagnation for the past few thousand years, but nothing could be further from the truth. Chinese history is just one apocalypse after another: foreign invasions, civil wars, ultraviolent peasant rebellions, or just the slow unraveling of the kingdom into chaos under a succession of weak rulers. So the incredible longevity of “China” as an entity has nothing to do with its stability, and everything to do with its ability to magically regenerate itself again and again. It’s what Nassim Taleb would call antifragile: every time the nation is torn to pieces by civil strife, it somehow knits itself back together, and every time the nation is conquered by barbarians, the barbarians get swallowed up and become Chinese. China has experienced at least six or seven events comparable in magnitude to the fall of Rome. The difference is that, unlike Rome, it always bounced back.

So the first of these occasions was the Warring States Period, which came on the tail-end of the Zhou Dynasty. The Zhou Dynasty was the earliest Chinese dynasty that’s well-attested historically,1 and it reigned for about 800 years, starting around the time of the Bronze Age Collapse in the Mediterranean, and ending around the time of the Punic Wars. What’s striking about the Zhou is how unlike later China it appears. There was no imperial bureaucracy, no Confucian literati class, no civil service exam. Instead, the Zhou emperors ruled over a patchwork of feudal nobles, European-style warrior-aristocrats bound by ties of kinship or marriage and constantly squabbling over titles and land. To a European, one of the most jarring things about later Chinese history is the lack of such nobles, but during the Zhou Dynasty they were there in force. In fact, over the course of those 800 years, the crown got weaker and weaker and the nobles got stronger and stronger, until the emperor was basically a figurehead and the most powerful dukes were effectively rival kings in their own right.

The warfare between these rival kingdoms got steadily more brutal, evolving from courtly chariot duels to massed infantry combat to wars of deliberate attrition and annihilation. Under this pressure, the duchies themselves evolved into highly centralized despotic nation-states. Actually, it all sounds a lot like late medieval Europe, only it happened two thousand years earlier. And also like late medieval Europe, this was a time of profound intellectual ferment. The warring states all craved legitimacy, and believed that they could get it by patronizing scholars and philosophers in the hopes that they would function as court propagandists.

But something went wrong. There were too many rival kingdoms, and it was too easy for a scholar to decamp from one to another if he was in demand. If a king didn’t treat his scholars with the proper deference, or if he established one particular school or philosophy as official orthodoxy and persecuted the others, then the offended intellectuals would all head over to his rival’s court instead. The meta-political system created a highly liquid market for sages, and horror of horrors: it was a sellers’ market. The result is known as the “諸子百家” or “the one hundred schools of thought.” You’ve definitely heard of the most famous of these schools: this is the scene in which Confucius made his mark, storming across the bombed-out landscape with his band of followers, hunting for rulers on whom he could try out his political and social theories.2 He even bumped into Laozi, the founder of Daoism, who was active at the same time and who preached a very different sort of philosophical reaction to an age of violence and dissolution.

But those are two schools, and I promised you a hundred. And indeed there were dozens and dozens more, some of them as weird as anything that ever slithered out of the internet. Actually, let me horrify every historian of Chinese thought with some internet-addled analogies. The early Confucians were the effective altruists of their time: earnest, utopian, full of energy, convinced the world was going to end if they didn’t do something. The Daoists were a bit like the post-rationalists: too cool for school, cultivating detachment, occupying a third position that transcended cynicism and idealism. But then you’ve got the Mohists: dogmatic utilitarian ascetic logicians who decided to master siege warfare to improve their bargaining power (don’t tell me the thought hasn’t crossed Yudkowsky’s mind). And let’s not omit the Agriculturalists (proto-communists who believed the world’s problems would be solved if people touched grass), who are not to be confused with the Naturalists (hippies dedicated to the study of woo). But perhaps the most fun are the Legalists, who are what you’d get if you turned the Lawful Evil D&D alignment into a fully worked-out philosophical system.3 No wait! I forgot about the Yangists. Yangism espoused the most extreme form of philosophical solipsism and egoism. It was said of their founder (who you’ll be shocked to learn was named Yang) that “if by plucking one hair he might benefit the whole world, he would not do it.”

And then, despite this astonishing intellectual diversity, the schools suddenly all hit on the same idea, which came to be represented by these words scratched out in the sand with a sword:

The words are: “天下” which literally translate as “under heaven” but mean something more like oikoumenē, the civilized, inhabited world. And the idea that they represented was: “The world is a chaotic, dismal, violent place in which innocents are constantly starved or massacred for no reason. The only solution is for one, single, universal empire to rule all.” Confucius was one of the first to hit on this idea, and for him it implied a glorious rebirth of the Zhou empire brought about by the restoration of its sacred rites and music. But soon his rivals the Daoists were writing that “just as the universe is ruled by the uniform and all-penetrating force of the Dao, so should society be unified under a single omnipotent leader.” And then the Mohists discovered that the perfect utilitarian outcome was actually for the most perfect and utilitarian logician/siege engineer to establish a centralized universal state. And so on for all the others. (Obviously the Legalists didn’t need any convincing.)

Pines argues that this remarkable intellectual convergence among such disparate philosophies happened because…it was incredibly obvious to everyone that the Warring States were destroying the entire known world. One of the most important disciples of Confucius, Mencius, coined the phrase “stability is in unity,” and it practically became the catchphrase of the entire intellectual elite. But notice how this instantly delegitimized all of the rival kingdoms! Or as Pines puts it: “Not a single individual is known ever to have endorsed a goal of a regional state’s independence… Denied ideological legitimacy, separate polities became intrinsically unsustainable in the long term. Having been associated with turmoil, bloodshed, and general disorder, these states were doomed intellectually long before they were destroyed militarily.”

It actually went further than that. Several of the competing philosophies justified their demands for a single empire on the grounds that mankind was once unified in the distant past, or (as with the Daoists) that the universe itself was an expression of unity. So, for the whole course of the rest of Chinese history, political fragmentation was treated as a grotesque aberration, with some crazy consequences. For example, centuries later, during the decline of the Tang Dynasty, rebellious governors couldn’t actually “secede” from the empire because definitionally there was only one empire. Since they weren’t quite willing to declare themselves the founders of a new dynasty, they had to acknowledge the ritual superiority of the Tang emperor even while defying his orders! Even the apocalyptic An Lushan rebellion maintained diplomatic relations with the Tang court and acted as if it were a foreign tributary seeking the emperor’s recognition. This ultimately allowed the Tang to keep the wheels on for centuries longer than they otherwise might have.

And when order did break down, “stability in unity” became a self-fulfilling prophecy for game-theoretic reasons that Pines puts beautifully:

Given the common conviction that reunification is the only viable outcome of an age of division, leaders of regional regimes had two possible modes of action. The first was to proclaim themselves dukes, princes, or kings, while recognizing the nominal suzerainty of one of the self-proclaimed emperors… insofar as the “king” acquiesced in his inferior status vis-à-vis an “emperor” elsewhere, his regional state was doomed. It was all too clear to every political actor that the existence of autonomous kingdoms was but a temporary aberration… Sooner or later, a truly powerful emperor would emerge, and it would be his duty to abolish deviant kingdoms and turn them back into prefectures and counties. Thus recognition of one’s ritual inferiority implied recognition of the provisional character of one’s dynastic rule.

An alternative to submission… would be to proclaim oneself an emperor, a new “Son of Heaven,” second to no one. This, however, implied… that he could neither coexist with other self-proclaimed emperors nor tolerate autonomous kingdoms, at least in the long term… Therefore, an aspiring “universal” emperor had to adopt an aggressive stance toward other regional potentates… it was well understood by all that the competition was a zero-sum game. A saying attributed to Confucius, “There are neither two suns in Heaven nor two Monarchs on earth,” required a life-and-death struggle from which only one legitimate winner could emerge.

Ironically, therefore, the idea of the singularity of imperial rule as the guarantee for peace ruled out the peaceful coexistence of two or more “emperors,” dooming the fragmented world to a bitter struggle, which allowed no real compromises, no territorial adjustments, and no sustainable peace agreements. Predictably, the strife between aspiring emperors turned into a nightmare of bloodshed and cruelty, which, in turn, enhanced expectations of renewed unification as the only feasible way out of mutual extermination. The notion that “stability is in unity” acted therefore as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But what counted as part of “天下”? Did it only include the traditional Chinese heartland (as roughly denoted by the frontiers of the Qin empire)? Or did it also include the “barbaric” peoples who lived in the desert, or on the steppe, or in the jungles of present-day Yunnan, or in the hilly massif of “Zomia”? Opinions on this fluctuated over the centuries, but the general view was something like this: the independence of the barbarians did not ipso facto pose an ideological threat or unsettle the universe in the same way that multiple Chinese nations might. But if the aliens did perform at least symbolic or ritual submission to the emperor, or took faltering steps along the transformation from “raw” to “cooked,” then that was a good sign that the emperor in question was a true sage who had heaven’s favor. Unfortunately, sometimes the barbarians had other ideas.

Much of the dramatic tension in post-unification Chinese history is provided by the steppe nomads who lived to her north and west. In the imperial histories they serve as a foil and antagonist for the civilized peoples of the river valleys, sometimes acting as allies and subjects, other times as raiders and reavers, and still other times as all-subjugating conquerors. Regardless, in official Chinese eyes they were the ultimate “other.” Somebody like James Scott or Christopher Beckwith might insist that no actually, the barbarians are the true heroes of the story, while implicitly agreeing that they represent a diametrically opposed form of life. The reality is that over the thousands of years of their encounter, the Chinese and the nomads rubbed off on each other.4 It’s pretty obvious on those occasions when the nomads conquered the Chinese and brought with them nomadic fashions and hairstyles and foods, but it also happened more slowly and subtly as the two groups just existed next to one another. And one of the most striking ways in which it happened was that the nomads developed their own notion of universal empire.

Once again, memes turn the wheel of history. By a certain point in history, every steppe nomad seems to have believed, deep down inside, that every so often the high god of the steppe, Tengri, would bestow his blessing upon a certain clan and a certain individual within that clan. Such a person could be identified by his charisma and daring and victory in every battle. That’s right, the nomads had an official belief in player characters. And like the Chinese belief in “stability in unity,” this also tended to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Whenever a young clan leader went on a winning streak, people would begin to whisper. A few true believers would defect to his banner. His army would grow, more battles would be won. Cynics seeing the way the wind was blowing would join up in the hopes that rewards would come to those who got in early. Then things would snowball, with nearby clans getting absorbed entirely, then larger groupings, then eventually entire nations. A few times in history the process got so out of control that the entire steppe unified itself behind one man, and the simultaneous thunder of a million hooves proclaimed woe to the whole continent. The “barbarian” cultural inclination towards orality and mutable identity greatly assisted this process because the tribes rallying behind a Genghis Khan, for instance, could actually become Mongols. At least…as long as he continued winning.

The barbarian belief in universal empire under a single man was like the Chinese belief in many ways. Indeed, the Chinese remember the exceptionally violent Mongol conquest in a more favorable light than anybody else on the Eurasian landmass. (Don’t get me wrong, Chinese literature is full of anti-Mongol diatribes, but the Yuan have always been considered a legitimate imperial dynasty, which is more than you can say for the Mongols most other places.) The reason is simple: they put an end to confusion and division, and restored unity to all under heaven. Even very soon after the conquest, you can find Chinese elites writing about how the advantages of unification outweigh the disadvantages of alien rule. Pause to think about how odd this is: a ruthless invader and occupier is considered more legitimate than the countless native dynasties which didn’t quite manage to unify the realm. This would be unthinkable most places, but it makes complete sense according to the logic of Chinese political culture.

But there was one very big difference between the steppe nomads and the Chinese when it came to universal empire: the barbarians believed that the favor of Tengri descended only upon exceptional heroes. An Abaoji, or a Genghis Khan, or a Tamerlane, or a Nurhaci might emerge and unite the tribes under exceptional circumstances, but if there was no man of sufficient bravery and daring on offer, then a period of disunity was normal and natural. In other words, universal empire only dawned for the nomads when a certain meritocratic bar was cleared, while for the Chinese the emperor was the Emperor no matter his personal foibles.

Some have considered this a paradox, because premodern China was relentlessly meritocratic in so many ways. Rather than being ruled by a hereditary military aristocracy, Chinese government was run by a scholarly elite selected via high-stakes written examinations. And yet at the apex of this hyper-selective intellectual pyramid sat a man with absolute unquestioned authority who (apart from dynastic founders) was there because of who his father was. And if you put it that way, it does seem a little bit odd. To resolve the puzzle, we need to look carefully at who the emperor was and what he meant to the Chinese.

For starters, the Emperor was not really an “emperor” at all according to the dictionary definition of the word. In fact, I have long been puzzled by this translation choice, and wondered about its history. The European idea of emperorship as invented by the Persians and perfected by the Romans has always connoted rule over a heterogeneous realm comprised of many nations or peoples. The Chinese emperor might incidentally do so, but the sine qua non of his office was that he ruled over all of the Chinese, full stop. If we were to invent words to describe the office, “ethnarch” might be a better one: the leader of a nation and culture and race. The actual word the Chinese use is “皇帝”, which is hard to translate but I definitely wouldn’t have picked “emperor”: in archaic Chinese, the first character “皇” meant something like “supreme” or “magnificent” or “august,” and the second character “帝” meant “god.” The ideogram itself probably evolved from a picture of an altar, or of a bundle of firewood used for a sacrifice. Emperorship was primarily a religious and ritual office. If you’re reaching for a European analogy it’s not the King of France, it’s the Pope. But now imagine that the Papacy was hereditary, and also ruled all of Europe.

The most important task of the emperor was the performance of certain rites that were necessary to keep the universe in balance. He was a semidivine entity, hallowed and set apart from the rest of humanity. His diet was carefully regulated to include only foods with the correct ritual meanings for different times of year.5 Upon his accession to the throne, it became illegal to speak or write the emperor’s name. Unlike a Greek or Roman ruler, the Chinese emperor’s image was not reproduced on coins because he was aloof, inscrutable, invisible, and omnipresent. He resided in a walled city within a city, and communication with him was almost impossible even for high officials. His body, clothing, and ritual implements were considered holy relics. If an edict was written in vermillion ink upon yellow silk, this signified that it came from the emperor personally, and upon receiving it even the mightiest general would “prostrate oneself and accept death” by lying face down on the floor until an emissary finished reading aloud the emperor’s words.

All of which goes to show why there always had to be an emperor, as opposed to the occasional and intermittent nature of universal rule among the nomads.6 Without an emperor, who would ensure that the sun and stars followed their courses correctly? We can also see why it was such an abomination for two emperors to exist at once, how it must have inexorably led to bad harvests, unnatural animal behavior, and the seasons arriving out of order. The ancient Chinese were famously pluralistic in matters of religion, accepting and integrating strange gods from foreign lands. Perhaps that’s because the only jealous god in their pantheon lived on earth. It was an exact conceptual inversion of medieval Europe: there could be many gods, but only one emperor.

All very well, and yet the theorists of this religious-political system had to deal with the fact that sometimes the emperor was a very bad man, or worse, an ineffectual nonentity. Here, the thinkers of the Warring States period hit upon essentially the same solution as the Catholic Church: an incredibly fine set of distinctions between the office itself and the man who happened to hold it. The emperor was worshipped not because of his virtues as a man, but because he was the emperor, and while a bad emperor might bring the wrath of the gods and calamity to the realm,7 he could not tarnish the divine nature of the office itself. Also like the Catholic Church, the Chinese engineered a subtle set of “checks and balances” that minimized the damage that could be done by an unworthy officeholder, while maintaining the theoretical omnipotence and supremacy of the office.

The first step in “deactivating” the theoretically supreme authority of the emperor was to drown him in ceremonial tasks. This worked well because the rites really were one of the core functions of his job. But over time, the official ritualists just kept multiplying the number and complexity of ceremonies the emperor had to perform, until it was impossible for him to fulfill them all even if he spent his entire waking life on them.8 This naturally left him with even less time for commanding the army, allocating the state budget, or important personnel matters — all of which conveniently got left to various bureaucrats who were from the same social class as the ritualists.

That same class of bureaucrats was in charge of raising the emperor’s children and heirs. Is it any wonder that their education heavily emphasized the importance of deferring to high officials of the state on all important matters of administration and policy? There’s a tendency in Chinese history for dynastic founders to be powerful and vigorous men, and for their descendants to be more and more worthless with each passing generation. This wasn’t biological degradation due to inbreeding or to heavy metals in the water supply, it was that their tutors and guardians exerted constant pressure to make the princes pliable and obedient, and with each generation there was less of a countervailing influence from an impressive and domineering father.9

Not only were they raised to be easy to control, they were also cut off from all direct sources of feedback or information about their realm. Remember how the emperor lived in a city within a city, removed and inaccessible to the populace? That cut both ways. The sovereigns were congenitally context-starved, fed a diet of information as carefully controlled as that used to train any AI. How could they possibly govern a nation that they had never seen or visited? Sometimes they got wise to what was happening and demanded to make an inspection tour of the realm, but there were always reasons this was impossible — security concerns, or budgetary considerations, or astrological and ritual restrictions. Only the most forceful and persistent emperors were ever able to see the land that they ruled.

While early dynastic leaders often personally led or accompanied their armies to the battlefield and crisscrossed the country on tours of inspection… their successors were more often than not confined during most of their career to the precinct of the Forbidden City or to other palaces, emerging only under duress, as when rebellions of invasions impended. This pattern is observable in any major dynasty, including even those established by the nomadic conquerors

Yes, including the nomadic conquerors. The conquest dynasties represent an extreme case of this recurring pattern of energetic founder followed by “deactivated” heirs. Remember that the nomad’s vision of universal rule was subtly different, in that they believed heaven’s favor did not descend upon every generation. Only the most worthy khagan or khan had a right to rule,10 and that cultural assumption was usually retained for the first few generations after the transition to emperorship on the Chinese model. Eventually, however, the inexorable Sinicization would win out — in fact Pines suggests that we should actually measure Sinicization by how much of a pushover the monarch had become.11

That brings us to the Imperial Chinese deep state: the scholars, officials, bureaucrats, and eunuchs who actually kept the empire running. Again, if you are coming from a European frame of reference, you are likely imagining a rural aristocracy, “men of quality,” burghers, merchants who managed to ennoble themselves, and so on. These groups, whom we may collectively term “local elites,” all existed in ancient China as well. Indeed, it’s probably a law of human organization that they must exist in all societies. And for a supposedly centralized absolute despotism, an extraordinary amount of the actual on-the-ground running things was outsourced to these elites.12 But they are not who anybody thinks of when you say “Imperial Chinese deep state.”

No, that would have to be the Confucian scholar-gentlemen, or literati. These were the direct intellectual descendants of the peripatetic scholars of the Warring States era. Following the Qin unification, they had made a devil’s bargain with the universal empire they’d memed into existence: they would be tamed and disciplined and serve the interests of the state, and in return they would receive an exalted role as moral guardians of the people and be given a guild stranglehold over all intellectual activity. The literati are called “Confucian,” and indeed venerated Confucius, but some of that is just branding. There were robust and fundamental debates within their ranks, all hidden within a very, very big tent called “Confucianism.” And they were the true glue that held China together.

The literati had an odd relationship with the state. While effectively all high officials were members of the literati (enforced via mandatory high-stakes examinations about the Confucian classics), and were expected to spend a bunch of their time writing and reflecting on philosophy and literature, not all literati worked for the state. Some of their most celebrated members went into seclusion, or returned to ancestral villages to properly perform the rites, or sought out mountain fastnesses where they could perfect their moral integrity. In effect they had a completely parallel status hierarchy from the rest of Chinese high society with its own awards and pecking-order and sacred values — a bit like academia today.

This in turn gave them tremendous power, even over the emperor. Chinese history is full of stories of “Confucian martyrdom,” where a gentleman scholar reproved the emperor in full awareness of the gruesome consequences that were likely to ensue.13 They did this because they cared more about the judgement of their peers than life or limb. And not just their contemporaries: the literati were the ones who wrote the histories, and whenever one of them acted fearlessly in defense of the prerogatives of his guild, he knew he would be commemorated as a virtuous man for centuries after. That power to shape history often meant that the martyrdom wasn’t actually carried out, because the emperors were well aware that punishing the dissenter could mean being condemned as a vicious and stupid ruler for the rest of history.

Every time this happened, it strengthened the position of the literati vis-a-vis the emperor (and naturally, such episodes were heavily emphasized in the educations of future emperors, further contributing to their “deactivation”). But it also strengthened the overall monarchic system as a whole, because these criticisms were always couched in the language of loyalty to the regime and disappointment in the fallible man currently in office. That is to say, none of the criticisms were “radical,” they were always “conservative” correctives to a deviation from an idealized past. This really shines through in the other way the literati cemented the hegemony of the imperial system: by shaping and guiding and ideologically neutering the many rebellions and civil wars.

China, as we’ve already covered, has had an explosively volatile political history. But there’s something a bit odd about it, too. The nineteenth century Sinologist Thomas Meadows put it this way: “Of all the nations that attained a certain degree of civilization, the Chinese are the least revolutionary and the most rebellious.” Rebellions happened constantly in China,14 and the literati often wrote about the sacred right of the people to rebel. Pines interprets the rebellions as a kind of “bloody popular election,” a mirror image of the theory of democracy as sublimated civil war that I wrote about here. These rebellions tended to start out hyper-violent, with a lot of very gratuitous and very sadistic killing, but they were hardly ever “revolutionary” in the sense of imagining a different regime. When the rebellion had gone on long enough, it would invariably converge back on the traditional model of an absolute monarch surrounded by meritorious officials, with commands effectuated by local elites.

It went like that all the way up until the creation of the Republic of China in 1912. And Pines argues this was because the literati never, ever defected. There simply wasn’t intellectual space for an alternative political and ideological system. Alternatives are proposed by intellectuals, and in ancient China the intellectuals had already decided where their loyalties lay. Well, it’s actually a little more subtle than that: the literati never defected ideologically, but they would often join the rebellion if it looked promising.15 But that sort of defection actually strengthened the imperial system — the traitor literati could confer ritual legitimacy on the rebellion, but in return they coopted it and could guide it in a non-threatening ideological direction.

Or as Pines puts it:

The intellectuals were the empire’s architects and custodians, and it was they who provided it with unparalleled cultural legitimacy. Even at times of crisis and disorder, when it seemed that the very foundations of the imperial polity had been irreversibly smashed, no alternatives to imperial rule were ever offered. Insofar as the stratum that determined right and wrong for the bulk of the population remained unwaveringly committed to the imperial political system, this system could withstand any domestic or foreign challenge, and could be resurrected after ages of the most woeful disorder and disintegration. It may not be a coincidence, then, that the end of the empire in the early twentieth century came shortly after the erstwhile intellectual consensus in its favor was shattered. Abandoned by its natural protectors, the empire fell with unbelievable ease, proving by the rapidity of its demise that throughout its history it had been primarily an intellectual rather than merely a sociopolitical construct, and that it owed its longevity overwhelmingly to the intellectuals, who designed it and ran it throughout the twenty-one centuries of its existence.

Yes, all things come to an end, even China’s eternal empire. A very different sort of regime now rules over the Chinese people, but in some ways it has to act just like its precursor. One of the themes of this Substack is that the sources of our present day identities, attitudes, and possibilities often lie in deep time. We may think we’ve figured things out for ourselves and are acting in our own interests, but actually we move in well-worn grooves carved out millennia ago by genetics, and by culture, and by the environment, and by the way those all influence each other. Like a long-running Broadway show, the actors age out and retire, but the roles stay the same.

So consider for a moment the issue of Taiwan: why is it such a flashpoint? In one sense it’s obvious: an unfinished civil war, a matter of national pride, and an island base from which the American Empire maintains a chokehold over Chinese shipping lanes. Who wouldn’t be touchy in such a situation? But dig a little deeper, talk to some mainland Chinese people, and you begin to hear echoes of a much older sentiment: “stability is in unity.” There cannot be two emperors, and to fail to unite the realm is to be ipso facto illegitimate.

The Taiwanese face the same tricky decision faced that independent duchies faced during premodern China’s periods of dissolution: acknowledge the temporary and provisional nature of your regime and doom yourself to ritual inferiority and eventual absorption, or declare yourself the true emperor and Son of Heaven and set up a zero-sum fight to the death. Perhaps the deep roots of political culture also explain the curious endurance of pro-mainland sentiment among the Taiwanese (and in Hong Kong), which has long confounded Western observers. After all, “分久必合,” the realm, long divided, must unite again.16

Many people believed that when Marxist-Leninist political fervor waned, China would embrace American-style liberalism to fill its ideological void. A lot of very big bets were made on that assumption, including the deliberate decision to tie China into the heart of global supply chains (and the concomitant loss of process knowledge and destruction of industrial capacity in Europe and America). Old people like me remember the triumphant articles in The Economist prematurely gloating about the impending democratization of China, and everyone assumed that the handover of Hong Kong in 1997 would act as a Trojan horse, infecting the mainland with Western ideas and attitudes.

It didn’t go quite the way they expected, did it? A lot of ink has been spilt as to why, but I think one under-discussed factor is that the Chinese are very aware from their history of the way that ritual inferiority inexorably leads to loss of sovereignty and political submission. They knew that if their elites were absorbed into the global elite monoculture blob, if they began listening to the same music and venerating the same holy symbols and adopting the same discursive conventions, then the inevitable result would be absorption into an alien empire. And unlike, say, many of the states in Central and Eastern Europe,17 they refuse to accept such a fate, because they believe that it is incompatible with the power and prestige that China deserves.

But disillusionment with communism (itself an alien ideology) has in fact left an ideological void at the heart of Chinese society. And if Western political theory is off-limits, then the only option is to reach back into China’s past, which is exactly what they’ve been doing. Fortunately for them, China has a rich intellectual history with plenty of solutions to offer. For the rest of us, it means the study of China’s past may be the key to understanding China’s future. Memes turn the wheel of history.

Traditional Chinese historiography states that before the Zhou came the Shang Dynasty, whose origins are shrouded in legend. Modern historians dismissed all of this as fanciful imperial mythologizing. If you read this substack a lot then you know what happened next: a succession of archaeological digs turned up burial inscriptions, etc. exactly matching the names of the Shang kings.

I could write an entire book review, or maybe a book, about how the stereotypical image of Confucius could not be further off the mark. He was not a white-haired cloud cuckoolander sage sitting in a pagoda on a mountain pondering things and issuing gnomic utterances. He was something closer to a cross between Machiavelli and a tech bro. Think “mercenary applied political theorist with a posse,” except he would occasionally get so fed up with his employers that he’d try starting a country himself.

One of the chief Legalists once argued that the way to attain victory was through “performing whatever the enemy is ashamed of.”

This also happened to the barbarians that the Romans faced.

From Fuchsia Dunlop:

In the first month of spring, [the emperor] was to eat wheat and mutton; in summer, pulses and fowl; in autumn, hemp seeds and dog meat; in winter, millet and suckling pig. An emperor’s failure to observe the laws of the seasons would not only cause disease, but provoke crop failure and other disasters.

The Chinese version of the nomadic belief was the theory of the “True Monarch” — once in every five hundred years, an emperor would arise who combined moral and intellectual perfection with the supreme authority of his office, and the whole earth would fling itself at his feet.

Yes! I pulled it off! I wrote an entire 6,000 word post about ancient Chinese political theory without using the phrase “mandate of heaven.” Oh nooooooo… I slipped up! Argh, now the moon has turned to blood and locusts are eating my barley crop. TIME TO REVOLT!!!

I am reminded here of the Eastern Orthodox approach to Holy Week.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that especially impressive or assertive emperors seemed to have partially “vaccinated” their sons against turning into nonentities. In this case I don’t think the main cause is heritable personal qualities, but rather the visible availability of an alternative model of emperorship to what the boy’s tutors are telling him he has to be like. One result of this is that we tend to see sequences of several good emperors in a row — most famously the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors in the early Qing Dynasty.

This commonly led to royal funerals among the nomads turning into giant bloody brawls or civil wars. After all, the moment the khaganate opens up is the moment to show just how qualified you are.

If you remember the bizarre Khitan political system with its strategic nomad reserve used as a source of imperial wives, that was all precisely designed to combat this problem.

David Friedman discusses this seeming paradox in his book Legal Systems Very Different From Ours. In fact the Chinese state not only devolved considerable authority to local elites (who were often little better than thugs), it also formally endorsed the absolute rule of the family patriarch over his relatives. Why would a state do that? Especially when we see modern states usually going to war with such mediating institutions instead? Friedman’s answer is that the imperial regime actually lacked state capacity, and that by outsourcing governance to third-party contractors it came out ahead even after they took their cut. (He also argues that Medieval European polities were making the same trade when they allowed Jews and other ethnic minorities to engage in substantial self-government.)

I’m reminded of this story from my review of Mote’s book:

One of the most respected Confucian scholars was brought to the palace and ordered to endorse the usurpation. When he refused and instead accused the new emperor of murder, he was beaten by the guards. Undeterred, he continued to revile and berate the emperor, who then ordered that his tongue be cut out to silence him. As the blood poured out of his mouth, the prostrate scholar used the tip of his finger to continue tracing out curses and accusations in his own blood on the palace pavement. Finally, he was taken away and executed by gradual dismemberment, and his relatives and associates exterminated “to the tenth degree of relationship.”

Not surprising to any fans of Crane Brinton in the house: rebellions inevitably followed periods of weakness, not harshness.

One of the most famous examples of this dynamic is Zhu Yuanzhang’s rebellion that led to the founding of the Ming Dynasty, which I wrote about here.

Or consider monarchism. When Pines wrote his book in 2012, the Communist Party seemed to have finally dispensed with this pillar of the traditional Chinese political system. Since the death of Mao and the end of his personality cult, the CCP was totally committed to oligarchy not just in practice but also in ritual and aesthetics. This oligarchy survived multiple transfers of power, not just between personnel but also between ruling factions like Jiang Zemin’s Shanghai clique, and so it was reasonable for Pines to concede that this was one thread with the past that had finally been broken. How ironic that just a few years later, China’s lurch back into monarchism was apparent to all.

The Poles and Hungarians seem to think that they can pick and choose which bits of liberalism they adopt. We will see how that works out for them. The Russians were previously on a course much like that of the Poles under their lib-Atlanticist President Putin (this has now been thoroughly memory-holed by both sides), but have now decided to pursue a strategy like that of the Chinese. Everybody else is trying to become an American colony as fast as possible.

I respectfully disagree. For starters, the discussion veers more than once into the very trap of assuming uniformity of China in time and in space right after (correctly) identifying and warning about said bias. But more importantly, it utterly misses the elephant in the room. Specifically, the Chinese writing system. Sure, it's super clunky inasmuch as it takes at least 8 years to learn in school. But crucially, this also means that people can speak totally differently, yet write exactly the same. In the pre-translation app world, when people from say Southern China visited Beijing, they would quickly realize they were speaking mutually unintelligible languages. No problem - then they would simply whip out a pencil and a paper and start writing.

I believe it was this far more than anything else that kept China together even in times of fragmentation. Were it not for this, chances are the Chinese would long ago have fractured into a group of related but separate nations, somewhat like the Germanic, Romance and Slavic languages of Europe, or similar groupings worldwide.

This is very interesting and I enjoyed it. I think the analysis of the memetic role of the Confucian academia in constraining the power of the emperors is probably quite right. But it's not enough to explain the situation.

The medieval Europeans did not accept the legitimacy of multiple states. They continuously invented new ways to tie themselves to imperial Roman titles ("Rex Romanorum," "Holy Roman Emperor," "Roman Catholicism"). The word "Catholic" means universal! Even HRE Carlos V felt this! In 1521, at the Diet of Worms, he said "“the empire from of old had not many masters, but one, and it is our intention to be that one.” That's explicitly saying multinational political organization is illegitimate.

Westphalia was remarkable because it was the first time in European political history that multinational political organization was accepted as per se legitimate! The meme of universalism is a core, core part of Christianity and European political thought up until very very recently.